Save Plants

Center for Plant Conservation

From the tiny seeds of White Meconella (Meconella oregana), to the sturdy acorns of Havard’s oak (Quercus havardii)—seeds come in a fascinating array of sizes, shapes, and colors. Seeds also hold the key to saving rare and endangered plants from extinction. At the Center for Plant Conservation (CPC), we maintain a collection of more than 2,300 of America’s most endangered native plants through our network of world class botanical gardens that safeguard plant material in ex situ botanical collections. Made up primarily of seeds, this National Collection serves as an emergency backup in case a species becomes extinct or no longer reproduces in the wild. Our partners work diligently to support the National Collection—making field trips to collect from wild populations, stewarding collections in seed banks, researching and studying seeds, germinating seed to grow new plants to reintroduce into the wild, and more.

In this issue, we highlight collaborative efforts throughout the CPC network to collect and bank seeds, and to research the behavior of seeds in long-term storage to advance our shared mission to Save Plants from extinction. We share an update on the Florida Plant Rescue—a state-wide, multi-partner seed collections initiative aiming to secure Florida’s rare plant species in conservation collections to prevent their extinction. Our partners at the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources and Preservation give insights into their research on a new method to predict seed aging to improve seed banking best practices as part of CPC’s IMLS-funded Seed Longevity Study. Finally, we celebrate long-time collaborator, Sheila Murray of The Arboretum at Flagstaff, as our Conservation Champion in honor of her commitment to collecting, safeguarding, and studying rare and native plants.

We are grateful to our conservation partners and our supporters who make possible our work to save seeds—and, ultimately, to Save Plants from extinction.

Safeguarding the Rare Plants of the Sunshine State

As home to over 3,000 native plant species, dozens of rich natural community types, and several centers of endemism within the state, Florida has immense importance as a biodiversity hotspot within the North American continent. Simultaneously, our state faces myriad challenges to preserving this botanical richness, including land development, habitat fragmentation, fire suppression of disturbance-dependent natural habitats, invasive species, and both direct and indirect impacts from climate change. With these threats to Florida’s rare plant species in mind, the Center for Plant Conservation recently began Florida Plant Rescue (FLPR), a state-wide initiative with the goal of preserving all of the state’s rare plant species in conservation collections. The focus of these collections is long-term ex situ seed banking, with alternative methods for exceptional species employed as needed. FLPR relies on the CPC network partners based in Florida to make, store, and maintain these collections. Membership currently includes: Atlanta Botanical Garden, Bok Tower Gardens, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Florida Native Plant Society, Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, Naples Botanical Garden, Institute for Regional Conservation, and Montgomery Botanical Center.

Our first collection season began in 2021, during which FLPR partners were able to target and collect from eight plant species of state and global conservation concern, ranging from the western panhandle all the way to very southern peninsular Florida. Thanks to generous gifts from anonymous donors as well as funding from the Band Foundation, FLPR’s collection capacity increased in 2022 and twelve additional species were collected and secured by partners.

Just to name a few of the recent collection accomplishments, Paronychia minima (paper nailwort), Tragia saxicola (Florida keys noseburn), Orbexilum virgatum (pineland scurfpea), and Rhynchospora megaplumosa (longbristle beaksedge) were all species previously uncollected and unrepresented in any conservation seed bank collection. Now, in addition to securing seeds from one population of each species, partners have learned invaluable, specific life history details and collection strategies for these plants. In addition to these traditional seed collections, Atlanta Botanical Garden has undertaken an exceptional species project to conserve Taxus floridana (Florida yew), an extremely rare, narrow endemic to slope forests east of the Apalachicola River that produces recalcitrant seed. By creating cuttings for ex situ propagation and establishing vitro cultures for cryopreservation, this species will be safeguarded for the long-term.

Considering the current 2023 collection season, our ambitions and capability have increased once again! This year, we hope to collect seed from populations of twenty species scattered throughout the state. For most of these species, this will represent their first-ever conservation collection made. Notable target plants include: Arnoglossum album (White Indian plantain) and Dicerandra modesta (blushing scrub balm), both species with less than 5 populations each in the state, and Carex lutea (golden sedge) and Portulaca minuta (Tiny purslane), both only recently discovered occurring in Florida. FLPR partners will also be starting work on two additional exceptional species projects, one each for Hymenocallis puntagordensis (Small-cup spiderlily) and Asimina manasota (Manasota pawpaw).

Deciding which plant species of the hundreds that are state-listed and that are tracked by the state’s natural heritage program to target for seed collections can be a challenge. With limited staff time and funds available for FLPR work each year, effective prioritization is key. Recent species conservation status ranking and taxonomic updates have led to the creation of an updated list of species that are of the highest priority for FLPR collections efforts. The 187 species on this list include 85 G1S1 species, 61 Federally listed species, and 122 species endemic to the state.

Looking toward the future, a major goal for the initiative is to provide to the FLPR partners a seed accession database that links collections to rare plant occurrence information from Florida Natural Areas Inventory (FNAI). This resource will not only help partners to spatially visualize where collections have been made, but will also function as a critical tool for the prioritization of future seed collections. Not by any means a one-way street, field data collected by FLPR partners and entered into the database will also help to update FNAI’s occurrence information. Thus, a beautiful positive feedback loop of data is born! Partners have already shared all their seed accession data with CPC and accessions have been linked to occurrences, so the accession database should be ready and available to partners later this year.

While we are proud of all that we have been able to accomplish under the umbrella of the FLPR project, we only look forward to achieving much more in the coming years. We hope to turn our tens of collections into hundreds and preserve the unique and diverse flora of the state for the long haul!

IMLS Seed Longevity Study: Researching the Aging of Rare Plant Seeds

How do you know when genebanked seeds need to be regenerated—or recollected? If the stored seed doesn’t germinate, is it dead or dormant? Successful genebanking depends on ensuring seeds stay alive in storage, but knowing how long rare seeds survive in frozen storage is hard to predict. In general, it is harder to genebank seeds from wild compared to cultivated species because there isn’t a lot of prior knowledge and wild seeds are more heterogeneous. In collaboration with the Center for Plant Conservation (CPC) and its network of botanic gardens in a study funded by the Institute for Museum and Library Services, we at the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources and Preservation (USDA-NLGRP) are using a new way to track aging rates of seeds from wild rare plant species. This work applies the usage of RNA integrity number (RIN) as a metric for seed aging, initially demonstrated for crop species.

Given the enormous variation wild seeds display in germination requirements and storage behavior, the adaptation of the RIN assay to measure seed health has been of interest and a focus of this collaboration. Our goal was to compare germination and RNA integrity (RIN) of fresh and stored seeds to see if measured changes correlate. This provided CPC partners the opportunity to recollect fresh seeds from the same plant populations as those visited over 15 years ago. The old seeds were stored dry at -18C, and so we could also ask which samples maintain high viability during storage—proof of concept that seed banking works.

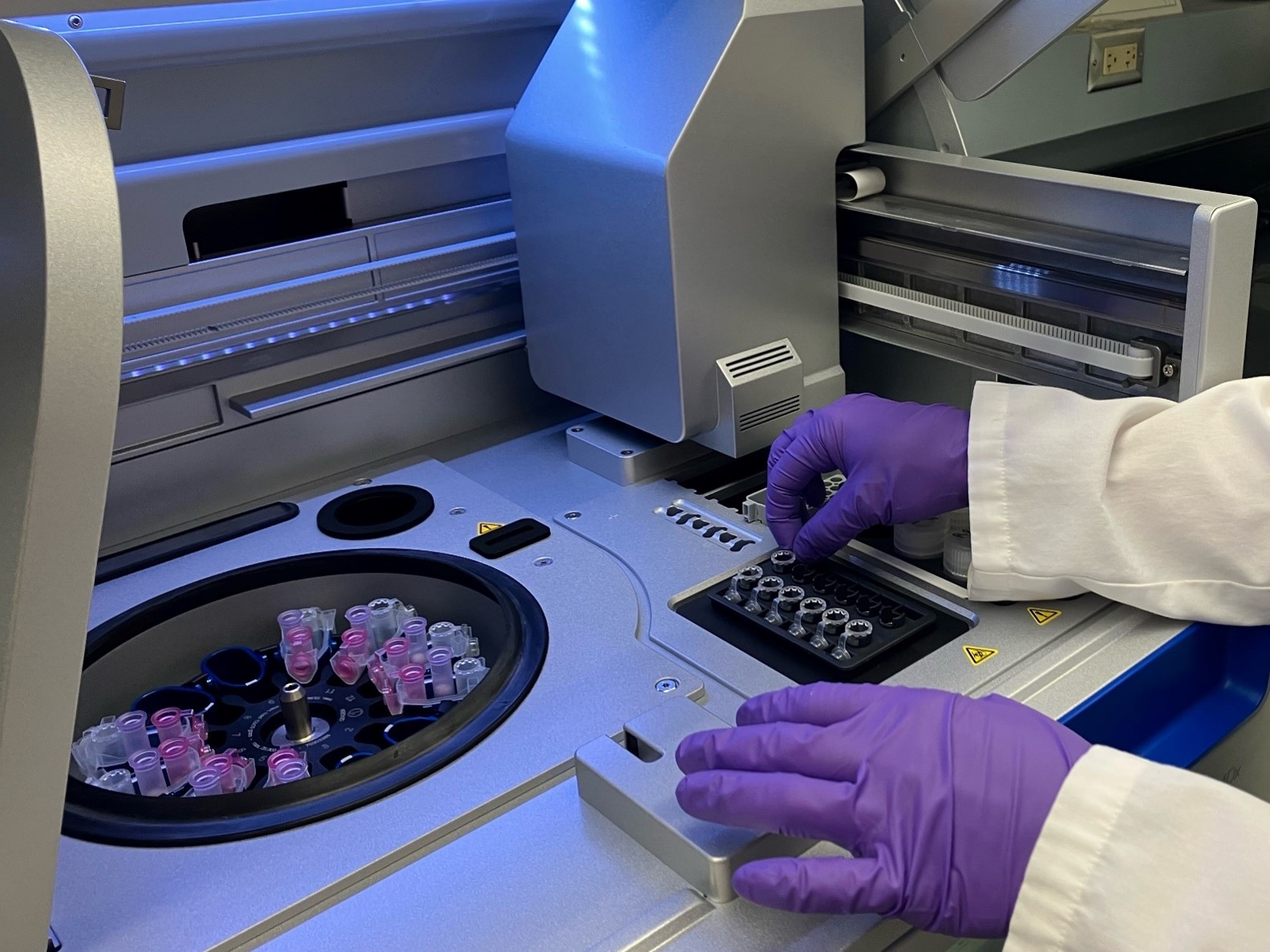

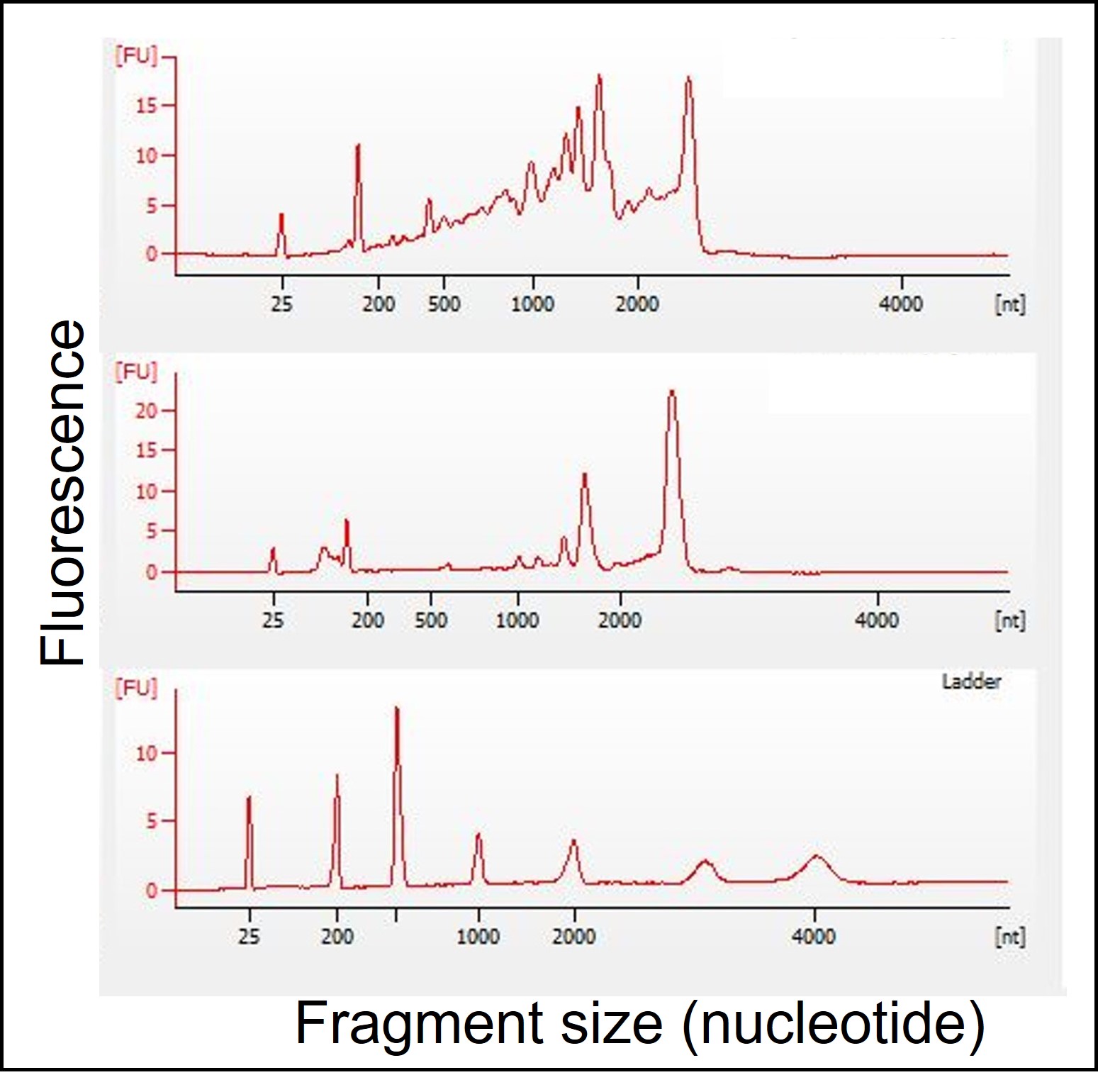

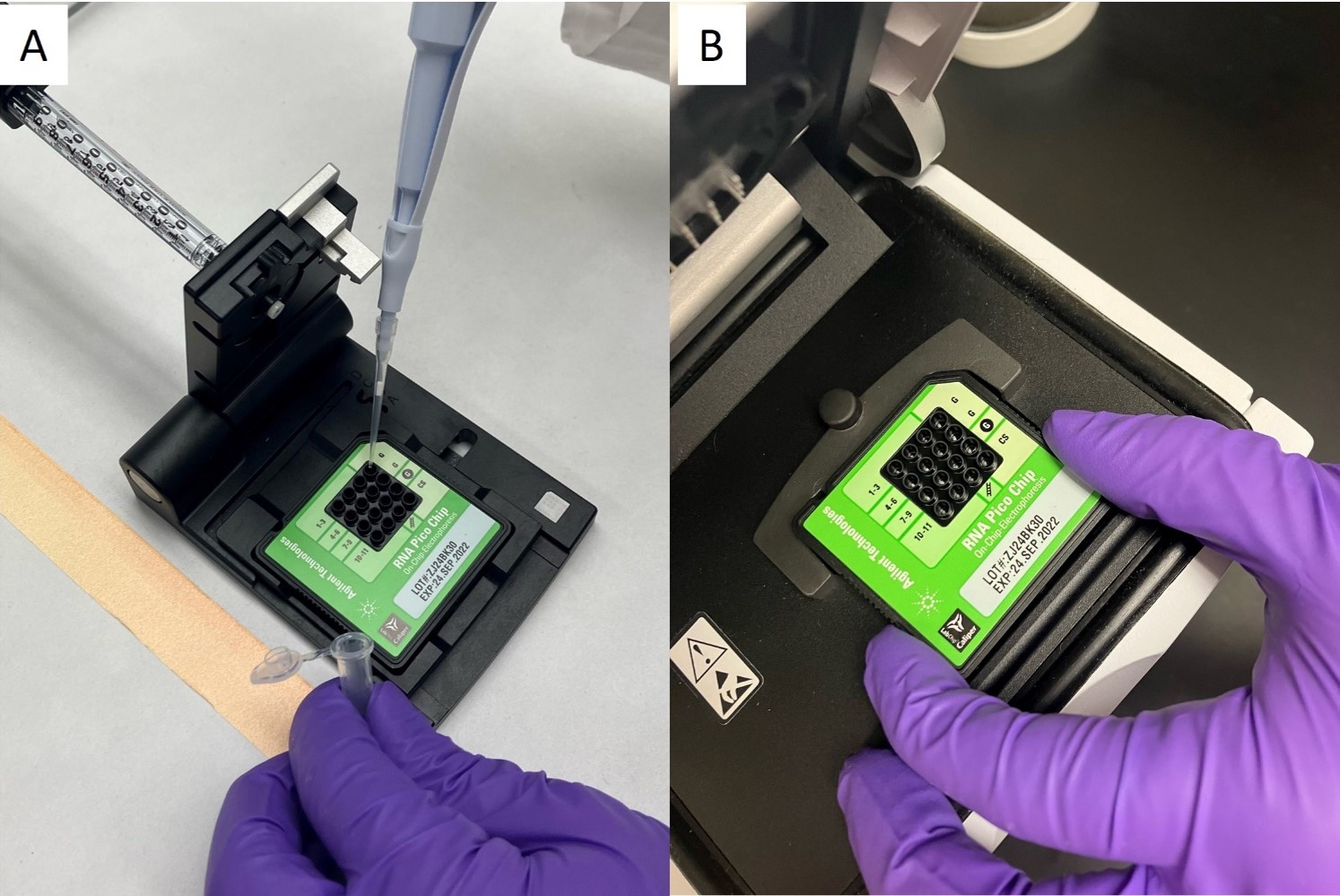

Genebanked seeds need an ‘exit plan’ in which they are used for restoration before they die in storage. Therefore, testing seed viability is a necessary, recurrent, and costly activity that consumes precious samples—especially for rare and endangered species. Unlike the traditional sigmoidal decline of proportional seed viability data, RNA integrity appears to decline continuously and linearly with storage time, opening the door for predictive modeling of seed health decline. RNAse activity is low in dry seeds and so fragmented RNA molecules accumulate and can be detected by extracting RNA using extraction kits and electrophoresing fragments using an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) to measure molecular size. Each RIN assay requires about 8-10 mg of seed tissue, preferably not including the seed coat.

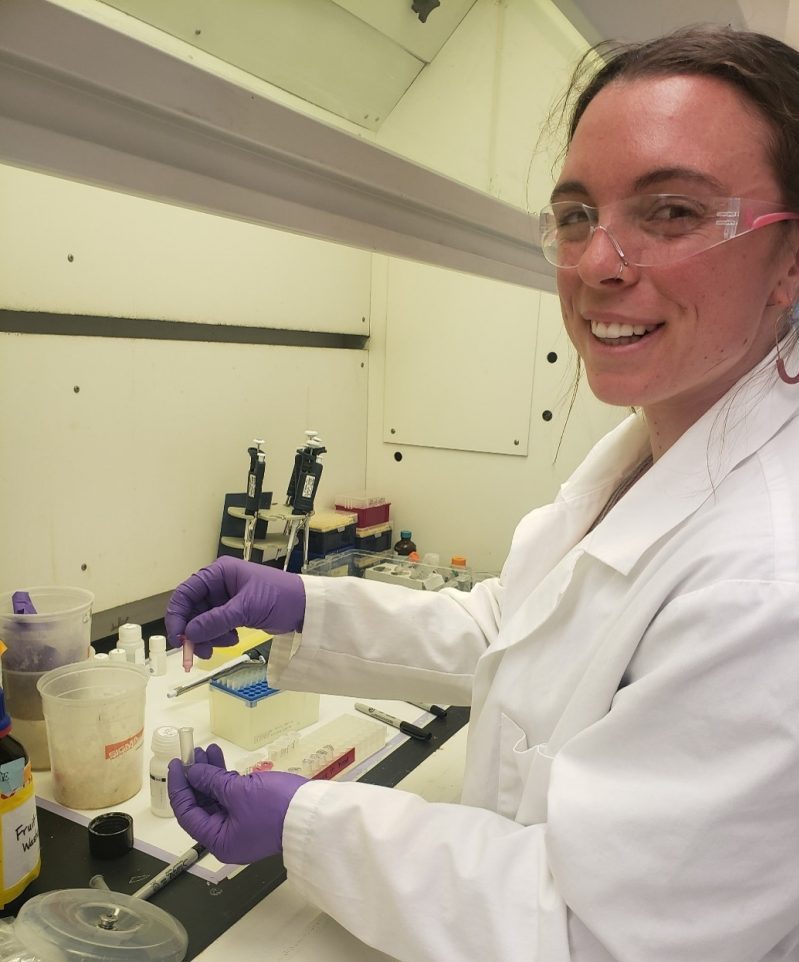

Applying RIN techniques to CPC species has introduced new variables that need optimization. For example, seeds from wild rare plants are diverse with variability in seed coat, seed size, and seed filling. Trying the easiest methods first, we extract RNA from fresh seeds with seed coats on using the standard Qiagen Plant RNAeasy RNA extraction method (Qiagen, Inc.). If the RNA quality is poor, we consider additional steps like removing the seed coat or using alternative RNA extraction kits such as Fruit-mate (Takara Bio USA, Inc.) followed by Nucleospin RNA Plant extraction kit (Takara Bio USA, Inc.) to avoid interference of polysaccharides or polyphenols (common when working with grasses or sedges).

Time is needed to dissect seeds or remove seed coats prior to RNA extraction to ensure high quality starting material for a successful RNA extraction. Each seed should be checked manually for the presence of an embryo, because extracting RNA from empty seed does not provide a RIN measurement that is representative of the seed health. About 1.5 years into the study, we have successfully extracted and analyzed RNA from both stored and fresh seed from 80 wild rare plant species, and we are aiming to complete the work using 100 species. The good news is that high quality RNA was obtained from older seeds in about 70% of the species pairs, suggesting that aging during storage was negligible or slight.

Germination assays use different amounts of seed than RIN and give different kinds of data. For starters, a germination assay may take months to complete and it requires 50-100 seeds, which can be a lot more seeds than RIN assays for large seeded species. Germination results can be inconsistent for the fresh and old seeds, leading to inconclusive information about the longevity. Overall, decline in germination and RIN appear similar, suggesting that RIN is a promising method to detect seed health in native endangered species. We are glad to be working with CPC to solve this difficult problem of seed longevity which will make genebanking of rare seeds more effective.

-

The Bioanalyzer uses electrophoresis to separate RNA fragments by molecular size (x-axis), with small molecules eluting fastest (RNA standard ‘ladder’ in the bottom electropherogram gives reference molecular lengths). The upper electropherograms indicate RNA quality from CPC seeds of Dodonaea viscosa (collected in 1990, top electropherogram) and Eriogonum cusickii (collected in 2022, middle electropherogram). In the upper electropherogram, there are a lot of medium-sized fragments in Dodonaea viscosa (200-1000 nucleotide region), indicating quite a bit of RNA fragmentation. RIN for this sample was 5.8 and germination for this sample was 72%. In contrast, there are few peaks in the medium-sized range in this Eriogonum cusickii sample which was given a RIN = 8.7. -

A) Preparation of an RNA Pico chip (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) for analysis on the B) Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.), for RIN of 11 CPC RNA samples. Photo credit: Lisa Hill. -

Testing viability of fresh and stored seeds requires breaking dormancy. In this example, we find that nearly all seeds from a 2021 sample of Amaranthus pumilus (from NCBG) germinate vigorously after a 4-month stratification at 5C. Photo credit: Shaimaa Ibrahim.

Sheila Murray

May’s Conservation Champion, Sheila Murray of The Arboretum at Flagstaff, is a long-time CPC network partner who advances our shared mission to Save Plants through her commitment to the conservation of the rare and native species that call the Colorado Plateau region of northern Arizona home. As a collaborator on CPC’s US Forest Service grant, Sheila supports seed collections initiatives on Region 3 USFS lands, helping secure vulnerable species–such as Goodding’s onion (Allium gooddingii)–in conservation collection. We are grateful for Sheila’s enthusiasm and dedication to her work, as well as her advocacy for the plants we work to save. As she states, “I think the best part of my job is talking to our community about the wonders of rare plant species and just how unique this area is…I like seeing their realization that these plants are important and precious…” Thank you, Sheila, for your work to Save Plants from extinction!

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I remember my childhood in Jerome, Arizona, walking with my parents and learning about the plants and the geology, and I think I realized then that I was in love with plants. We lived on the edge of our tiny town, and most days were spent outdoors in the yard and vegetable garden or hiking up the mountainside. Jerome is a high desert mountain environment with lots of different microclimates and plant diversity. We’d marvel at the red bark of the manzanita and sweet Ceanothus flowers. I remember that feeling of being able to recognize certain plants as comforting and being at home, and knew plants were what I wanted to study and find a career working with.

What was your career path to the Arboretum at Flagstaff

I started my career at the Arboretum at Flagstaff with an internship right out of college. I received a Bachelor’s degree in Environmental Science from Northern Arizona University in 2001, and soon after took a summer internship with The Arboretum in their Research Department. My intern work was quite varied working with invasive species projects and with our rare plant conservation program. After the summer position ended, I jumped right into a full-time position in the department, and over the years have become the sole member of the department which we now call Conservation. Our work is primarily focused on the rare plant species of the Colorado Plateau.

In your experience what are some of the pressing conservation needs impacting the rare and native plants of Arizona?

I think one of the biggest challenges in protecting imperiled plants in Arizona is habitat loss, both from development and from climate change. The Southwest has some of the largest areas of public land in the United States as well as some of the largest increases in population and development. Habitat loss can happen with urban expansion near and adjacent to public lands which also increases the utilization pressures on those lands. Wildfire season has expanded from being a summer event to being a potential hazard year-round. As conservationists we can help land managers by providing knowledge on plant communities and best practices for conservation and restoration after such disturbances. One of the strongest tools we have is securing rare plant seeds through seed banks, giving us some time to find the best way to protect species long-term.

What conservation project(s) are you currently working on? What successes or challenges have you encountered in your work?

Currently I’m working on gathering more information about a rare species only found on one mountain in one place on Earth—the San Francisco Peaks Ragwort (Packera franciscana). This diminutive daisy is only found in the alpine areas of the San Francisco Peaks, which is a mountain just north of Flagstaff, AZ. Climate change is a serious and immediate threat to this species and to any other species found in alpine tundra. We want to learn more about the life history of the species, how it grows and how we can potentially propagate it for ex-situ storage. A method that has not been examined before is vegetative propagation, and we will take a look at that option in our greenhouse. A challenge lately has been gaining any access to the wild populations. We had severe drought for a long time which ushered in a number of significant wildfires, and last year most of the area where the population grows had been burned and closed to the public. This winter provided the region with the opposite, we had record-setting snowfall and long-lasting snowpack. It seems likely that this summer could be a great one for the plants, and we should be able to access the populations to gather our vegetative cuttings. Once back at the greenhouse, we will look at different ways to propagate them and then keep them on display in our rare plant refugia garden. Figuring out this method of propagation could potentially provide plants for future reintroduction. Any information we learn about this species is crucial for its conservation.

What has surprised you about working with and learning more about rare plants?

What surprises me every day is just how many people are still unaware of the plight of rare plants, but then how excited they can become when they learn about how wonderful plants are and how important it is to protect them. I think the best part of my job is talking to our community about the wonders of rare plant species and just how unique this area is. I like seeing their realization that these plants are important and precious, and how lucky we are to live here now where we can experience such fabulous plant diversity, and hopefully how we can help take action to guarantee that these plants continue to thrive for future generations.

What advice would you give to those who wish to learn more about how they can help save imperiled plant species?

My advice to those who want to learn more would be to go out and experience our ecosystem as much as possible. It’s amazing how spending time in nature can be restorative and can get your mind-gears turning towards fascination, wonder, and inquisitiveness about plants. If you’ve already got the curiosity going, there are many experts at the Arboretum and at all our great public gardens around the country who are happy and excited to speak with you about what they’ve got going on and how you might get involved. At the Arboretum we have a number of ways to volunteer to help save imperiled species, and we are always looking for helping hands. One opportunity is to become a Rare Plant Ranger, one of our volunteer citizen scientists who help us keep tabs on a long list of rare species around Flagstaff.

-

Left, Sheila Murray collecting seeds. Right, Packera Franciscana. Images by Kristin Haskins -

Sheila collecting cuttings from Purshia subintegra, the Arizona Cliffrose in the Verde Valley, Arizona. Photo credit: Joyce Maschinski. -

Kaibab Plateau Indian paintbrush (Castilleja kaibabensis). Photo credit: Sheila Murray, courtesy of The Arboretum at Flagstaff.

Welcome To New CPC Board Members

The Center for Plant Conservation (CPC) is pleased to be adding two new members to its Board of Trustees, each bringing a wealth of knowledge, unique professional experiences, and a profound enthusiasm and commitment to CPC’s mission to safeguard imperiled plants. As executive directors of two of CPC’s Participating Institutions, they will bring a welcome perspective to our work. We thank them for joining our team and supporting our efforts to Save Plants!

Lee Clippard (Austin, TX)

Lee Clippard is the executive director of The University of Texas at Austin Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. He has been a member of the leadership team at the Wildflower Center since 2014, and prior to serving as executive director, he led the Center’s communications, marketing, plant information and guest experience efforts. Lee holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from UT Austin and a master’s degree in entomology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Before joining the Wildflower Center, he was the Senior Director of Communications for the UT Austin College of Natural Sciences. He is a native plant and natural history enthusiast committed to plant conservation and supporting botanic garden efforts to transform lives and create beautiful, resilient environments.

Paul Redman (Kennett Square, PA)

As President and Chief Executive Officer of Longwood Gardens for the last 16 years, Paul has implemented institutional and strategic reforms that have positioned the Gardens as a premier horticultural, cultural, and educational institution of the 21st Century, while respecting the values of its founder, Pierre S. du Pont. Paul is currently leading Longwood through its most ambitious expansion in a century to further the Gardens’ mission of sharing beauty with the world. Longwood Reimagined: A New Garden Experience is a sweeping reimagination of 17 acres of the Conservatory and grounds. Opening in fall 2024, the $250 million project features stunning new buildings, including a 32,000 square foot crystalline glass house that seemingly floats on water, state-of-the-art education facilities, a dynamic new restaurant and event space, and inviting new indoor and outdoor gardens. In addition to his work at Longwood, Paul is active in advancing the horticulture industry and raising awareness of the important role of public gardens around the globe.

National Collection Spotlight: Sand Flax

Sand Flax (Linum arenicola) is a critically imperiled species endemic to southern Florida. There are 13 known extant occurrences of this rare species, and it is listed as Endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act. Linum arenicola lives predominantly in southern Florida’s pine rocklands, which have seen widespread development and land conversion. Because of this, habitat loss and fragmentation are major concerns for this rare plant.

Linum arenicola is secured in the CPC National Collection at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, where the species is held in orthodox seed banking. When collecting seed from this species from wild populations, conservation scientists at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden needed to make several trips to the few plants remaining in wild populations. Due to the small size of the plants, their sporadic flowering, and their minimal seed production, repeated trips were required to gather adequate amounts of seed.

Learn more about conservation actions taken for Sand Flax on its National Collection Plant Profile, and help support critical conservation work for this species with a Plant Sponsorship.

As Seen on CPC’s Rare Plant Academy: Assessing Sites In the Field before Conservation Seed Collection

Prior to making conservation collections from wild populations, it is important to conduct site assessments of your target populations. In this Rare Plant Academy video written by Jason Ligon of Atlanta Botanical Garden’s Southeast Center for Conservation, discover some methods to conduct site assessments for most effective conservation collections. These site assessments allow you to ensure your conservation collection maximizes genetic diversity represented ex situ without harming the population you are collecting from. Important factors to consider include population size and fecundity to account for how much seed can be collected from each individual in each year. Check out the “seed collection” tag on the Rare Plant Academy Video Library to watch many more videos and learn more methods for conducting conservation focused collections!

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Ways to Help CPC

Conservation Advocacy Initiatives

Act Now: Support the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act!

After narrowly missing passage in the last congress, Recovering America’s Wildlife Act (RAWA) has been reintroduced in the Senate with bipartisan co-sponsors Sen. Heinrich (D-NV) and Sen. Tillis (R-NC).

This bill would be an unprecedented investment in rare species conservation that could directly benefit our conservation partner programs. RAWA would provide $1 billion to states, tribes, and agencies to implement Wildlife Action Plans including extinction prevention strategies for species of greatest conservation need.

RAWA likely could come to a vote in the Senate late April. Currently, the Senate is on recess and public support is needed to secure additional votes to ensure passage. Now is the time to act by encouraging as many people as possible to contact their senators.

Contact your representative directly and urge them to support RAWA!

Donate to Save Endangered Plants

Without plants, life as we know it would not be possible. Yet two in five of the world’s plants are at risk of extinction. More than ever before, rare plants need our help!

That is why all of us at the Center for Plant Conservation (CPC) are deeply grateful to have you as part of our conservation community. Your generous and unyielding support allows CPC and our network of world-class botanical institutions to make great strides in our shared mission to Save Plants from extinction.

Your gift ensures CPC’s meaningful conservation work will continue. Together, we save more plants than would ever be possible alone—ensuring that both plants and people thrive for generations to come. We are very thankful to for all that you do to help us Save Plants!

Donate to Save Plants Today!

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today