save Plants

Center for Plant Conservation

When it comes to plants, there are countless unique, captivating, and exceptional species that we share our planet with. However, in the world of rare plant conservation, “exceptional” takes on a different meaning. Exceptional species are those that cannot be conserved long-term using traditional seed banking methods. This includes species—like oaks, cycads, and magnolias, to name a few—with few or no seeds available for banking, species with seeds that are intolerant of desiccation and freezing (recalcitrant seeds), or seeds that do not have prolonged viability in ex situ (offsite, away from the wild population) storage. No matter the reason, exceptional species require alternative ex situ conservation methods to ensure they are safeguarded from extinction—presenting both challenges and opportunities for innovation as practitioners research and establish the most effective ways to conserve these species.

In this issue, The Huntington shares insights into their cryobiotechnology program and efforts to develop and optimize methods to conserve magnolia species in liquid nitrogen, and we spotlight the work of several Florida Plant Rescue partners who are collecting and establishing conservation protocols for exceptional species endemic to the Sunshine State. Lastly, we celebrate the work of our Conservation Champion Dr. Joe Ree, Postdoctoral Associate at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, whose research into the use of cryopreservation and tissue culture to preserve oak species deepens our understanding of conservation strategies for this highly endangered exceptional species group.

Efforts to conserve exceptional species play a critical role in our ability to preserve the vast biodiversity of our rare, native flora. Our network of Conservation Partners are at the forefront of scientific and technological advancements that help us better understand—and better protect—these truly incredible exceptional species.

The Huntington Cryobiotechnology Program: Magnolia Case

Since 2014, The Huntington Botanical Gardens has established projects focused on designing and optimizing plant cryobiotechnology tools, including tissue culture and cryopreservation techniques. We also maintain in vitro repositories for different groups of plants with particular interest in conservation, such as aloes, agaves, avocados, magnolias, and oaks. The in vitro repositories (tissue-cultured plants under regular and slow growth conditions) allow short and middle-term conservation of plants, and they are available for distribution or reintroduction in the field. The Huntington Cryobiotechnology program also focuses on strategies from collecting plant material to rooting and acclimating before the plants return to field conditions. Here, we present a case study on magnolias.

According to the Red List of Magnoliaceae, half of the Magnoliaceae taxa are worldwide threatened with extinction. The magnolias are mostly appreciated as ornamental plants; their perfume and timber are considered for industrial use, and some species are studied for their potential use as medicinal plants. Besides the in situ conservation of those taxa, developing efficient ex-situ conservation methods plays a crucial role in maintaining Magnoliaceae biodiversity.

Although seed and field banks are the traditional methods for the ex-situ preservation of plant species, seeds from many magnolia species cannot be seed banked. Therefore, the long-term conservation of these plants can be assessed using cryobiotechnological methods. More than 60 accessions of more than 40 magnolia taxa have been introduced in vitro. Some represent endangered species collected at The Huntington and other field collections or from natural populations in Alabama, Florida, Puerto Rico, and Mexico.

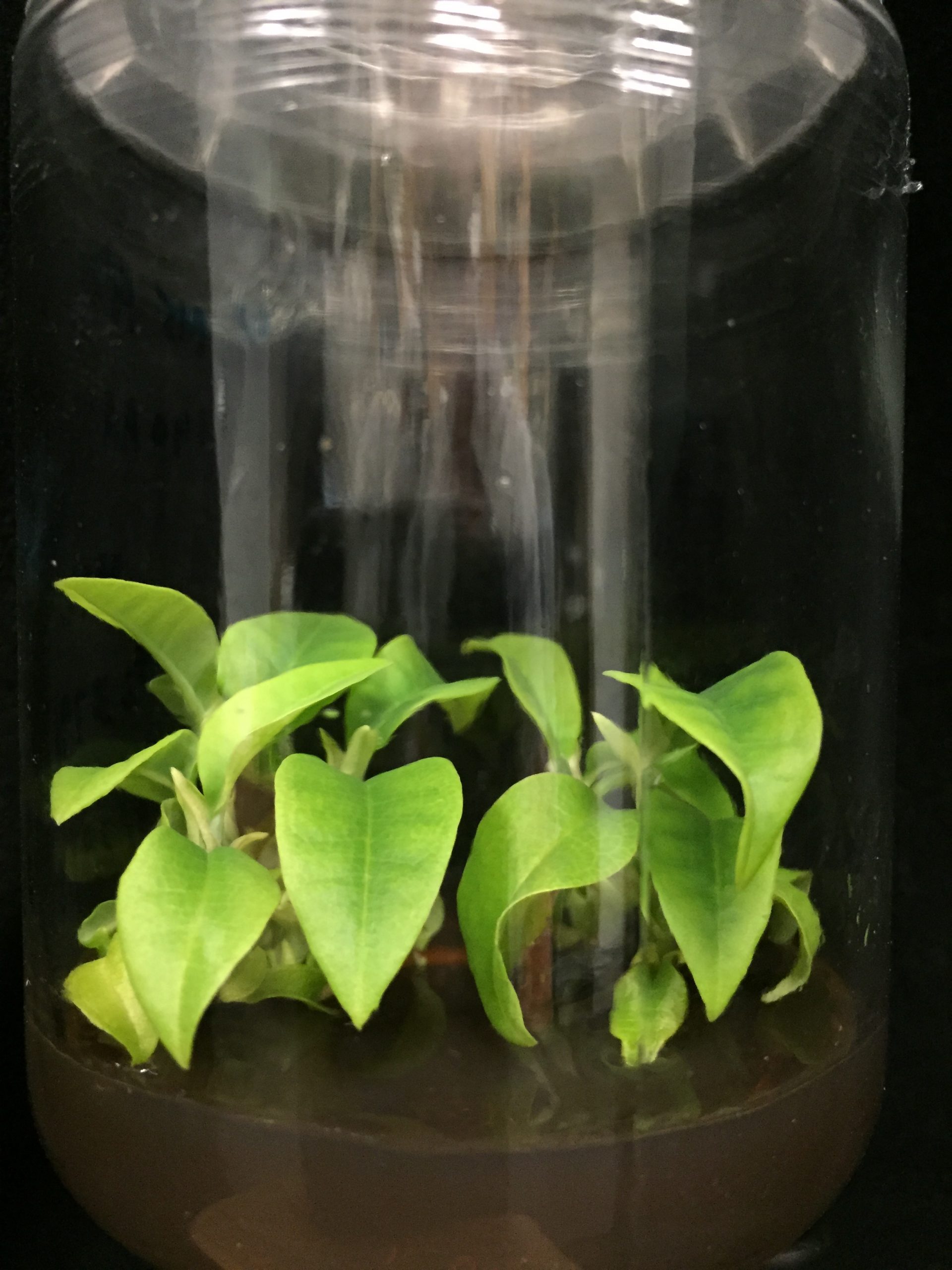

At The Huntington, we have optimized micropropagation protocols for some magnolia species, resulting in a tissue culture collection of more than 35 taxa and representing the world’s first in vitro repository for clonal magnolias. Additionally, we have been optimizing the rooting and acclimation of the in vitro shoots to the ex-vitro conditions. The studies resulted in the production of rooted plants that have been planted at The Huntington and other botanical gardens.

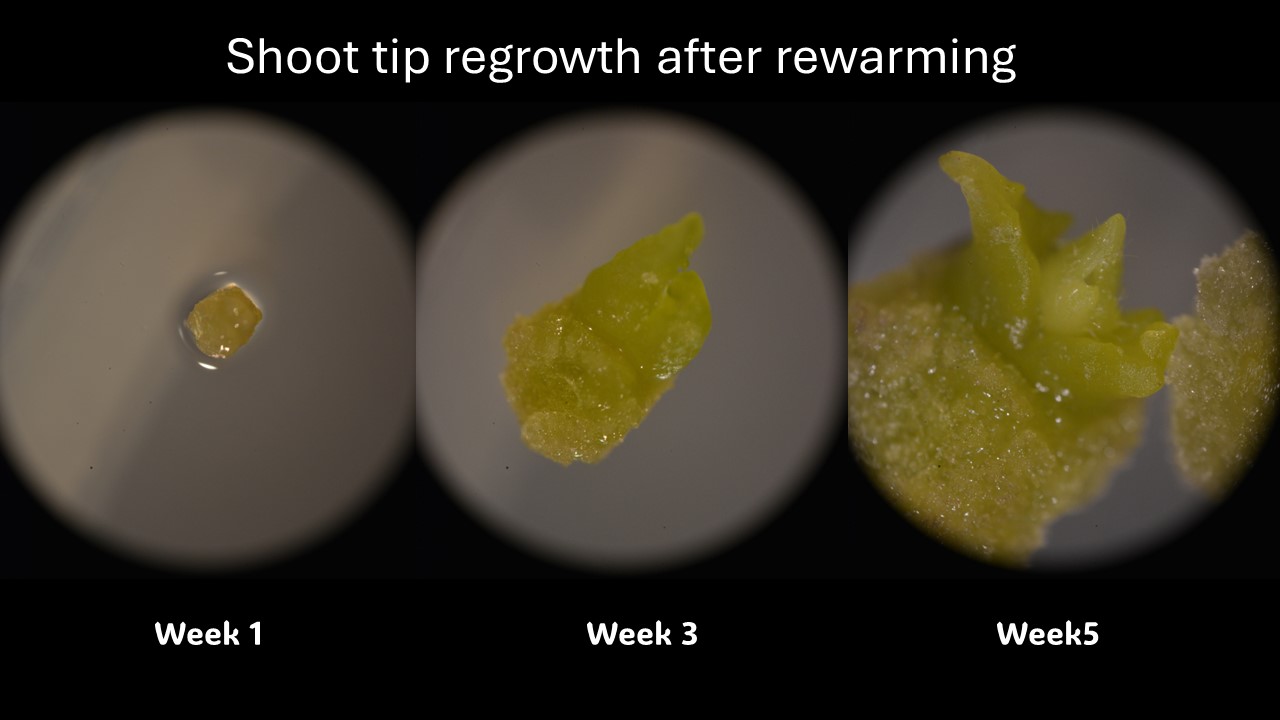

We developed the first cryopreservation protocol to conserve meristems from magnolia, using a plant of Ashe’s magnolia collected at The Arnold Arboretum. More cryopreservation studies are underway, and the final goal is to obtain standard methods to bank trees and shrubs from wild-collected magnolias. Altogether, it will allow for a reduction in costs and the risk of loss of important species.

Florida Plant Rescue: Conserving Exceptional Species in the Sunshine State

The Florida Plant Rescue (FLPR) initiative’s ultimate goal is to secure all of the state’s rare plant species in conservation collections. For most species, this means traditional seed collection and banking. However, some species have seeds that don’t tolerate orthodox seed banking methods, or seeds whose behavior is unknown. A critical aim of FLPR involves establishing conservation protocols for these exceptional species, and each year FLPR partners are invited to propose exceptional species curation projects.

Many factors are considered when proposing exceptional species projects, including existing information on the species’ storage habits, storage behaviors and established protocols for closely related species, research necessary to establish methods for the target species, and plans for curation of the conservation collection. Since the initiative’s formation, three exceptional species projects have been carried out by FLPR partners, helping to inform storage behavior and develop storage protocols for three rare Florida plants and their relatives.

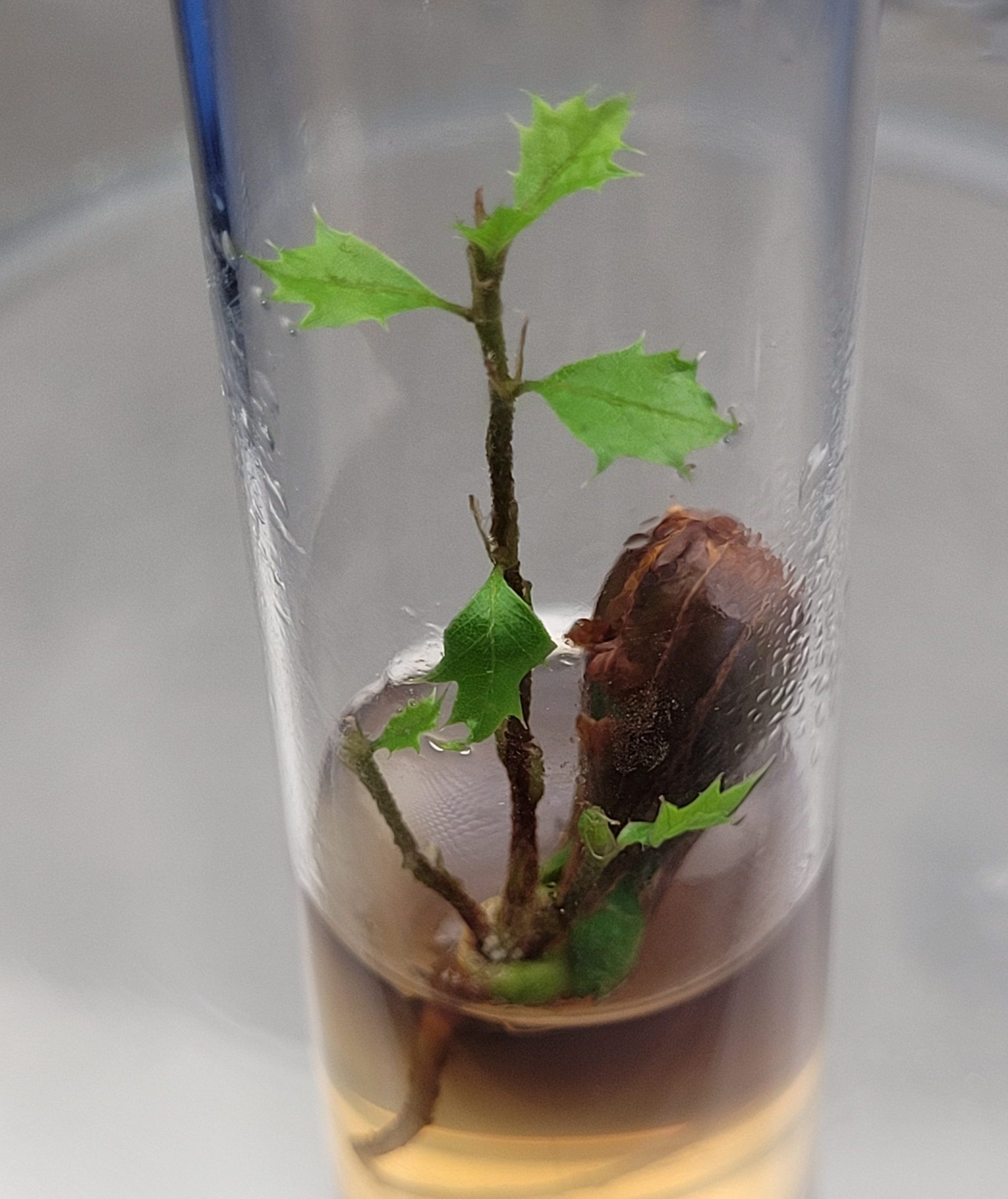

In 2022, CPC funded Atlanta Botanical Garden (ABG) to undertake an exceptional species curation project for Florida Yew (Taxus floridana), a narrow endemic that produces large, recalcitrant seeds intolerant of the drying required for orthodox storage. Using their extensive knowledge of the closely related Florida Torreya (Torreya taxifolia), ABG staff developed a protocol for ex situ propagation of Florida Yew and successfully established wild-provenanced cuttings in their conservation greenhouse. ABG staff have also established an in vitro tissue culture protocol for Florida Yew, opening the door to more exciting conservation work for the species. Next steps for this project involve using material from established plants from the cuttings collected in 2022 to initiate new in vitro cuttings.

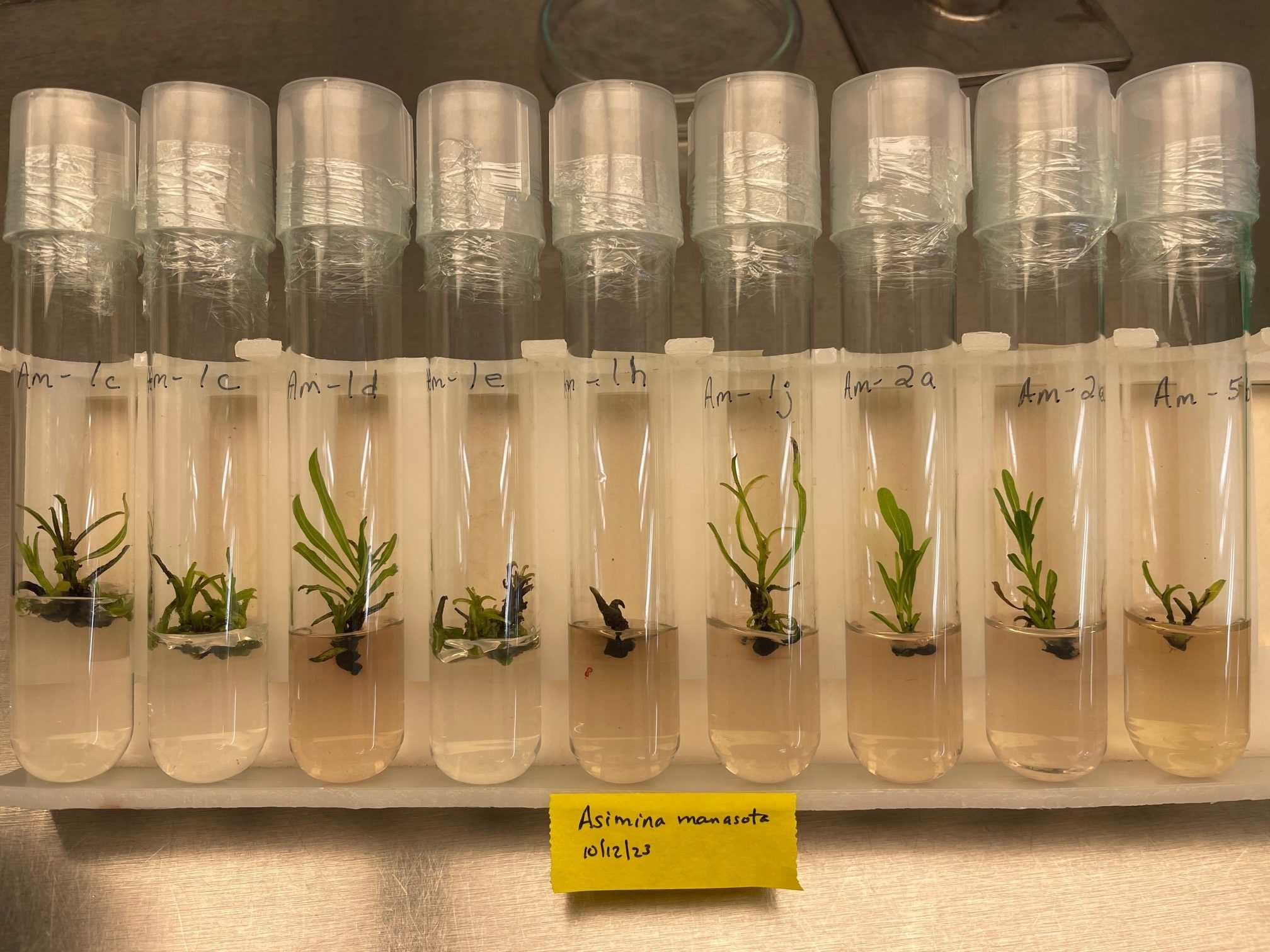

Last year saw two new exciting exceptional species projects, one focusing on Manasota pawpaw (Asimina manasota) from Marie Selby Botanical Gardens (MSBG) and another from Naples Botanical Garden (NBG) aimed at the conservation of Punta Gorda spiderlily (Hymenocallis punta-gordensis). MSBG’s work with Manasota pawpaw, a narrow endemic from the central west coast of the state, targeted a genus well accepted to require exceptional methods for long term storage.

In partnership with the Lindner Center for Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife at the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden (CREW), MSBG staff collected immature shoot tissue from wild individuals of the species to be grown in tissue culture, processed, and cryopreserved. Armed with experience establishing protocols for related species, CREW staff successfully grew three germplasm lines from the material collected in the wild by MSBG staff in 2023! The MSBG team aims to collect tissue from Manasota pawpaw in situ again this year, in the hopes of further tissue culture propagation and long-term storage in cryopreservation.

Naples Botanical Garden’s work with the endemic Punta Gorda spiderlily entailed extensive scouting to locate the 4-inch-tall lily on the Fred C. Babcock/Cecil M. Wildlife Management Area, where they were able to collect 29 seeds representing 11 unique maternal lines. This species naturally occurs in seasonally inundated areas, where seeds are often dispersed in water, and are intolerant of drying. The wild-collected seeds were brought back to NBG, where staff germinated seeds and established seedlings in the nursery at a high success rate. These established plants will be maintained as a living collection and used for seed bulking, allowing NBG to produce more seed from the 11 maternal lines and establish more plants, with the goal to use material for tissue culture and cryopreservation in the future.

The detailed findings reported by partners conducting exceptional species projects expand the initiative’s collective knowledge of exceptional species curation, contributing to each focal species’ conservation as well as to our overall understanding of the myriad of methods applicable for species unable to be traditionally seed banked. As FLPR continues to secure Florida’s rare plants in conservation collections, the initiative also continues to share and expand upon conservation knowledge. We look forward to the successes that 2024’s collection season will bring to the ambitious initiative, stay tuned for news on future exceptional species projects!

-

Taxus floridana showing new axillary buds in a test tube on June 12, 46 days after inoculation. Photo credit: Qiansheng Li. -

Asimina manasota (Manasota pawpaw) is a narrow endemic documented from 2 Florida counties. This species has been targeted for ex situ conservation as part of the Florida Rare Plants Initiative. It is an exceptional species that will require methods other than traditional seed banking. Photo by Bruce Holst. -

Asimina manasota plants growing in vitro at the Lindner Center for Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife at the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden (CREW). Photo credit: Valerie Pence.

Dr. Joe Ree

Our March Conservation Champion, Dr. Joe Ree, brings a life-long love of plants and innovative spirit to his work at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance where he leads research into the use of cryopreservation and tissue culture to preserve endangered oak species, with an emphasis on California scrub oak (Quercus dumosa). His pioneering efforts not only deepen our understanding of these exceptional species but also pave the way for more effective conservation strategies that are crucial for safeguarding the biodiversity of our native flora and our planet’s ecosystems. Joe embodies the commitment to collaboration that is the hallmark of CPC’s conservation community. As he says, “We’re not going to save imperiled species by ourselves. This is a team effort…as that network grows, so does our ability to protect the life that makes our world beautiful.”

When did you first fall in love with plants?

It’s hard not to fall in love with plants when you grow up in the Willamette Valley of Oregon. Fir, pine, cedar, maple, cottonwood, and oaks grow tall, hiding the horizon behind a green curtain. When my parents took my sister and I to see Mt. Saint Helens a little less than two decades after it erupted in 1980, we first visited the on-site museum, where I saw pictures of these forests laid low from the eruption. Old trees felled by the fury of the Earth. I thought of the forest in the nearby park close to my home and imagined what it would look like if it burned too. I still remember how much distress I felt at the thought.

Then we walked outside of the museum to see how the landscape had changed in the intervening years. Those fallen trees were mostly still there, but among them were flowering bushes and saplings. Butterflies flitted here and there, and birds sang from their perches of broken trees. In the background rose the half-destroyed volcano, but all around it was a carpet of life growing from the destruction it had created. When I suffer a setback, I think about that forest. From ashes, life. From difficulty, perseverance. In a way, those forests became part of my soul and inseparable from my sense of self. Only a particularly rough period of grad school shook that belief, yet I regrew and here I remain, working with plants.

What was your career path to researching cryopreservation and tissue culture methods for the conservation of plant species?

My undergraduate major at Oregon State University was BioResource Research, which required writing an undergraduate thesis based on working in a lab. I visited several labs and each lab amazed me with their lines of research. When I visited the Forest Biotechnology Laboratory and walked into their tissue culture lab filled with shelves of poplar trees growing on agar, I thought a single word: “Yep.” I’ve worked with tissue culture ever since, and I have no intention of changing if I can help it.

After working in an industrial lab after college, my then-girlfriend and now-wife had to move back to Brazil. Luckily, the local university had a graduate program that heavily focused on tissue culture. I applied and was accepted, learned Portuguese, hopped on a plane, and then spent six years and change working with South American palm trees in tissue culture. The cryopreservation work became a priority after a major aspect of my doctorate project fell through (the rough period I mentioned above). I became obsessed with the intersection of physics and biology. Water molecules orienting themselves into sharp, sea urchin-like balls of expanding needles became the face of the enemy. I learned many ways of defeating that enemy in palm somatic embryos, and I hope that many of the same methods apply to oaks.

Based on your experience and research, what are some of the pressing conservation needs impacting the U.S.’s rare and native oaks?

The threats to our oaks are legion: invasive grasses that drown saplings in shade, more frequent and hotter fires, diseases that rot the roots of mature trees, roving packs of feral bulldozers, and the perennial dread that is climate change. We might be able to mitigate those threats, but they will remain. While they remain, they will whittle away the genetic diversity of our oaks. Decreasing genetic diversity reduces the ability of oaks to adapt to a changing world. We need more people capable of tissue culture and cryopreservation and the facilities to perform the needed work.

With these technologies, a tree can be sampled, cultured, cryopreserved, and remain unchanging in the ultracool temperatures of liquid nitrogen for years, decades, and, perhaps, centuries. If the original tree is destroyed, we can take the sample from cryo, regrow it, and return it to nature—at least in theory. This technology is still in its infancy, but it is a technology that we need, and we need it now. More hands, more eyes, more thoughts, more effort, more tests, more collaboration, more everything, because the one thing we will never have is more time. Besides the technology aspect, another thing we can do is encourage and support citizen science. For example, I’d like to state my appreciation for the work of Jim Crouch of Escondido, CA, who is growing Engelmann oaks (Quercus engelmannii) and working with land owners to plant them. Planting trees in our time is a gift for future generations.

What conservation project(s) are you currently working on? What successes or challenges have you encountered in your work?

I developed an effective protocol of harvesting fresh stems from oak and other chaparral plants and culturing them in tissue culture, but several major objectives remain. Cryopreservation of stem tissue is difficult, so I am developing the means of creating asexually-derived embryos from leaves and stems, which tend to survive cryopreservation more effectively. It is, unfortunately, quite a complicated process requiring multiple more steps.

Plants grown in the lab must be acclimated to greenhouse conditions because those plants never had to worry about dehydrating, had all their needs met without effort, never felt the bite of an insect, or ever felt the force of a breeze. The shock of moving between agar to soil is often lethal. I’m developing new methods to ensure that that shock is mitigated. One of the methods I am most excited to research is the use of native mycorrhizal fungi to help the oaks adapt to what, to them, must be a strange new world. In nature, mycorrhizal fungi and oaks have a tight relationship. Mycorrhizae transfer nutrients to the tree, and the tree transports photosynthesis-derived sugars to the mycorrhizae. However, in the dry climate of Southern California, this relationship has an additional facet: water.

Oaks tend to make deep roots to tap into ground water. They bring up water from the depths for their mycorrhizae, while the mycorrhizae spread through the soil to find pockets of moisture within the sandy soil. With my colleague Ruby Iacuaniello, who knows far more about finding and identifying fungi than I do, we are trying to culture these fungi in tissue culture so that we can inoculate the oaks with their symbiotic partners even before we plant them.

What has surprised you about working with and learning more about oaks, or rare plants in general?

For every paper with a focus on a rare plant, there seems to be a hundred papers focused on a domestic species. This makes sense—maize affects our day-to-day life more than, say, the Del Mar manzanita. Agriculture tends to focus on elite cultivars, the prized breeds created for greater yields, disease resistance, or other beneficial characteristics.

The published research focuses on how to cultivate these few elite individuals perfectly in tissue culture. I can’t do that for my oaks, because my goal is creating the means of cultivating the majority of the entire species in tissue culture. My focus is then not on creating ten thousand tailored suits, but a one-size-fits-most boilersuit. Such a thing is rare in the published literature.

Most oak research revolves around Mediterranean species like cork oak, but several groups in the United States have published work on our own oaks. I can’t speak for those groups, but it sometimes feels that I’m on the frontier with a half-sketched map with ‘here be dragons’ scribbled in the margins. I find I like the adventure, as I can climb a metaphorical mountain, say of the cultivation of the Del Mar manzanita in tissue culture, and I can be relatively sure I am the first to ever climb that mountain. I am afraid that I might have narrowed the areas in which I can be happy in my profession, because no amount of work with maize cultures can ever match that realization.

What advice would you give to those who wish to learn more about how they can help save imperiled plant species?

All effort is a worthy effort. We’re not going to save imperiled species by ourselves. This is a team effort. You don’t need to spend fifteen years reading tissue culture and cryopreservation research articles to have a beneficial impact that will reverb across the generations.

As the proverb goes ‘a society grows great when people plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in.’ What I do is but one aspect of what is required to ensure that these species will never fade from the Earth. Ask yourself what you love to do. I love lab work, so I work in a lab. There might be volunteering opportunities if that sounds appealing to you. I’d like to thank Mandy Butler, who generously volunteers her time helping me in the lab just about every week. If you love gardening, you can embark on a project to replace non-native ornamentals with native ones. If you love the outdoors, there might be opportunities to help with land restoration work. You can write to your local representative to voice your support for measures that protect rare plants. Citizen science, especially citizen science that gives room for people to join and collaborate not only helps, but it creates a tight network of people able to share knowledge. As that network grows, so does our ability to protect the life that makes our world beautiful.

Welcome to CPC: New Partners

At the core of the Center for Plant Conservation’s (CPC) work is our conservation community—people and organizations that support and contribute to our conservation mission and vision of a future where plants, people, and our planet thrive. These conservation practitioners and researchers, advisors and partners, donors, and plant enthusiasts help make our work possible, and we are thrilled at the ways in which our community has broadened and strengthened over our 40-year history—and continues to do so.

CPC is excited to welcome a new member to our Board of Trustees, Arabella Dane, as well as five new institutions to our network of Conservation Partners. Now 80 members strong, the CPC network brings together plant conservationists from world-class institutions across the globe and is grounded in the spirit of collaboration and scientific innovation to save imperiled plants from extinction. Read on to learn more about the newest members of our community!

Arabella Dane

CPC Board of Trustees | Milwaukee, WI

Passionate about conservation, native plants, and their pollinators and habitats, Arabella is currently serving as a board member of the Native Plant Trust and the Center for Plant Conservation. She has compiled a plant database of over 150,000 plants and is continually adding images of these plants and the butterflies and other pollinators that frequent them.

A National Garden Club Master Flower Show Judge, Master Landscape Critic, and Gardening Study Consultant, Arabella serves as a member of the National Garden Club’s Board. She has recently become a NH Master Gardener, volunteering through the extension service based at UNH. The recipient of the Garden Club of America’s 2020 Achievement Medal, she is a member of the North Shore GC in MA, the Ashland GC in NH, and more recently the Green Tree GC in Milwaukee. Her lectures and articles on photography and on conservation topics are popular with garden clubs and other groups.

She recently finished her term as chair of the Boston Committee of the GCA, an association of 9 GCA Clubs and 3 affiliated clubs that help worthy organizations to protect the open spaces in and around Boston, many of these properties are part of Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace. She is a Garden Club of America Flower show judge in Horticulture, Design, and Photography, and is the Photography Society of America individual membership director for New Hampshire.

The Dane’s Hillcrest Farm in Center Harbor, NH has been documented and accepted into the Archive of American Gardens at the Smithsonian. The property includes formal gardens, whimsical components, play areas, and farm animals in addition to a wild meadow and a stand of chestnut trees where pink lady-slippers grow with abandon. A photography instructor, a Photography Society of America judge, and member of several photography organizations and camera clubs, Arabella gives programs in person and via Zoom. She has competed successful in numerous international competitions. Enjoy some of her images here.

Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories and Arboretum

Collaborating Partner | Charlotte, NC

Bartlett Tree Research Laboratories and Arboretum is a 60-year-old collection of almost 30,000 accessions of woody and perennial plants with an increasing conservation focus. Funded by their parent for-profit company, Bartlett Tree Experts, the arboretum serves to house both collections of conservation priorities as well as research collections for the fields of botany, horticulture, arboriculture, and similar interests. Botanical research is a new realm Bartlett is rapidly expanding into, utilizing their molecular lab on site that is also used for diagnostic purposes within the company. They collaborate with botanic gardens, universities, nurseries and other stakeholders in the botanical and horticultural realms and are spearheading the much-needed Global Conservation Consortium for Crataegus, which has become a priority genus for Bartlett as they build up a living reference collection with the goal to spark further research into this genus.

City of Albuquerque BioPark

Participating Institution | Albuquerque, New Mexico

The ABQ BioPark is a living environmental park that protects the natural world and connects communities with nature with the mission of fostering meaningful connections between people and nature. It is a refuge for thousands of animals and plants cared for by zoological, marine and botanical experts who lead significant science-based conservation work in New Mexico and around the world. The BioPark consists of four distinct areas: ABQ BioPark Aquarium, ABQ BioPark Botanic Garden, ABQ BioPark Zoo, and Tingley Beach. It is an Association of Zoos and Aquariums accredited, accessible facility that has earned the American Humane Certified™ seal of approval for its excellent treatment of animals and commitment to conservation. Welcoming more than 1.5 million visitors per year, ABQ. BioPark is the top tourist destination in the state of New Mexico.

The ABQ BioPark Botanic Garden collections include ornamental and native plants designed in garden-theme plant communities. These gardens include a children’s garden, a desert and tropical conservatory, an orchid collection, a desert-adapted Japanese garden, a medicinal plant garden, a high desert rose garden, and a heritage farm. ABQ BioPark maintains collections of many rare plant species and a seed bank.

Oregon Department of Agriculture – Native Plant Conservation Program

Network Partner | Salem, Oregon

The Oregon Department of Agriculture’s Native Plant Conservation Program oversees the conservation and management of Oregon’s listed plant species, including: assisting federal, state, and local government agencies with the management of state protected plant populations found on their land, including consultations for impacts to listed species and development of management plans and conservation programs; issuing permits for scientific research and habitat restoration projects involving listed plants; conducting research to enhance protected plant species recovery efforts; and periodically reviewing listed species and candidate species for potential reclassification, removal, or addition to the State’s list of threatened and endangered plants. The NPCP is involved in many conservation projects throughout the state, and assists land managers with listed plant species on their properties and works to support recovery goals for Oregon’s listed species.

The Jones Center at Ichauway

Participating Institution | Newton Georgia

The Jones Center at Ichauway was founded in 1992 with a mission to understand, demonstrate, and promote excellence in natural resource management and conservation. Within the Jones Center, the Plant Ecology lab focuses on understanding and conserving the floristic diversity of the southeastern Coastal Plain through long-term studies and rare plant monitoring and seed collections. The Jones Center maintains a seed bank of more than 1,000 accessions of 68 species, the majority of which are S1-S3 species in Georgia and has a shadehouse bay dedicated to rare species propagation and with raised beds for living collections. As the Plant Ecology lab continues surveying for, monitoring, and collecting seeds from rare species throughout southwest Georgia, the Jones Center also looks forward to the opportunity to work with the Florida Plant Rescue program and become an ex situ site for rare plants from northwest Florida.

University of South Florida Botanical Gardens

Participating Institution | Tampa, Florida

The mission of the Botanical Gardens at University of South Florida is to foster appreciation, understanding and stewardship of our natural and cultural botanical heritage through living plant collections, displays, education and research. The Botanical Gardens serve the education and research needs of the University community and provides education and recreation opportunities to the Tampa Bay Area community.

The USF Botanical Gardens is committed to the conservation and education about Florida’s native plants and plant communities. They currently have approximately 200 species of native woody plants in their collections, a native wildflower/grass “meadow” comprised of more than 100 herbaceous species, a Florida scrub planting with approximately 30 species of scrub and sandhill species, and a littoral zone planting with more than 30 species of woody and herbaceous plants. USF Botanical Gardens currently has 54 plant species in their public collection that are state and/or federally listed, including 10 scrub species and four pine rockland species. USF Botanical Gardens intends to be a major source of education regarding Florida native plants, their conservation needs and their use in home landscapes to create habitat for wildlife.

Reminder: Register for the 2024 National Meeting

There’s still time to register for the 2024 National Meeting! Sessions will take place May 2-3 at the San Diego Zoo and Safari Park, in collaboration with the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance—a CPC Participating Institution and the host institution for CPC’s National Office headquarters. This year’s meeting theme, Conservation Innovation: Harnessing Technology to Advance Rare Plant Conservation, celebrates CPC’s milestone 40th anniversary and our network’s innovative spirit that drives our collective conservation efforts and success stories. Don’t miss exciting conservation updates from the CPC National Office, lightning talk presentations from our network partners, breakout group sessions and more.

The last day to register is April 15!

2024 National Meeting Highlights

40th Anniversary Summit

Conference-goers and rare plant enthusiasts are invited to join the Center for Plant Conservation for a special pre-conference summit event in honor of CPC’s 40th anniversary. Blending celebration with purpose, the event aims to highlight the significant strides CPC and its network of Conservation Partners have made over the past 40 years and to generate crucial funds in support of CPC’s mission to save plants from extinction. Attendees will have the unique opportunity to hear from a distinguished panel of leading experts in the field of plant conservation, providing insights into groundbreaking innovations shaping the future of conservation efforts. A reception with drinks and light fare will follow this enlightening discussion—a perfect culmination to an evening dedicated to safeguarding the botanical diversity that enriches our planet.

The event will be hosted at the San Diego Natural History Museum on Wednesday, May 1 from 7-9 p.m. Learn more.

If you have already registered for the conference and would like to add registration for the Summit, please contact info@saveplants.org.

Seed Longevity Study Working Group

During the 2024 National Meeting, CPC will host a special capstone workshop of its Institute for Museum and Library Services-funded study about the predictors of seed longevity in conservation seed banks and the application of RNA integrity as a metric of seed ageing. We invite study participants and meeting attendees to learn more about the results of the study, presented by our partners at USDA ARS National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation, and give feedback on how they would apply the insights of the study to their own curation practice.

National Collection Spotlight: Havard’s Oak

To thrive in the harsh conditions of the Great Plains of America is no small feat. For flora and fauna alike, the extreme weather creates an unforgiving environment. With so little coverage for protection, and scarce food sources, it’s no wonder that Harvard’s oak (Quercus havardii), also commonly known as shinnery oak, provides shelter to so many small creatures. Found across Arizona, Colorado, Oklahoma, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, and Utah, Havard’s oak has seen a recent decline due to industrial agriculture coming into conflict. Due to this threat, our institutional partners have taken steps to protect the future of Havard’s Oak.

As exceptional species that cannot be conserved long-term via conventional seed banking methods, the threatened oaks of the United States, including Quercus havardii, are at the forefront of the conservation efforts of many of CPC’s Conservation Partners. The Morton Arboretum and the The Huntington have taken steps to preserve Havard’s oak.

We encourage you to learn more about Havard’s oak on its National Collection Plant Profile and help support critical conservation work with a Plant Sponsorship. In celebration of our 40 years of saving plants from extinction, CPC’s 40th Anniversary Campaign is raising funds to sponsor 40 National Collection species, including Havard’s oak. For every $5K raised per plant species, our Board of Trustees will provide $5K in matching funds to bring the species to the full sponsorship level of $10K–doubling the impact of your gift in support of rare and endangered plants!

As Seen on CPC’s Rare Plant Academy: Cryopreservation of Rare Plants Video Series

Cryopreservation is an important frontier in the conservation of exceptional plant species, whose seeds cannot be stored in conventional seed banks. Learn how CPC’s network partners are utilizing and innovating cryopreservation methods to support their conservation efforts in a featured video series on the Rare Plant Academy (RPA), highlighting some of the world’s foremost experts in plant cryobiotechnology.

In this video from the series, USDA’s Jennifer Kendall discusses how cryopreservation is used at the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation to preserve clonal material—that is tissue that contains the exact same genetic makeup as the source plant—in liquid nitrogen.

You can find the full cryopreservation video series on the RPA homepage or search the RPA Video Library using “cryopreservation” in the keyword search. Learn more about cryopreservation best practices here.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Ways to Help CPC

Conservation Advocacy Initiatives

CPC’s network is working hard to Save Plants, and you can help by using your voice. Be a rare plant advocate!

How can you help advocate for rare and endangered plants? Stay informed, contact your representatives about legislation related to conservation, and involve your friends and family!

On the Advocacy page of our website, you can find federal legislation in the U.S. that the CPC is tracking with a direct effect on rare plant conservation. You can also read CPC’s Position Papers and learn how you can help be your best endangered plant advocate.

For more information and more ways you can help, check out the Get Involved tab on CPC’s website. In addition to rare plant advocacy, you can learn what it means to be a Plant Sponsor and sign up for our newsletter to receive monthly conservation updates from the CPC network.

Donate to Save Endangered Plants

Without plants, life as we know it would not be possible. Yet two in five of the world’s plants are at risk of extinction. More than ever before, rare plants need our help!

When you support the Center for Plant Conservation (CPC) by making a charitable gift, you help advance our mission to safeguard rare plants by advancing science-based conservation practices, connecting and empowering plant conservationists, and inspiring all to protect biodiversity for future generations.

Your donation makes it possible for CPC to offer educational resources that support and train our botanical community, advance science-based conservation research, maintain the National Collection of Rare and Endangered Plants, and so much more.

The Center For Plant Conservation is a 501 (c) (3) non-profit organization (EIN# 22-2527116). Your gift to the Center for Plant Conservation is 100% tax deductible.

Your gift ensures CPC’s meaningful conservation work will continue. Together, we save more plants than would ever be possible alone—ensuring that both plants and people thrive for generations to come. We are very thankful to for all that you do to help us Save Plants!

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today