CPC Best Plant Conservation Practices

to Support Species Survival in the Wild

to Support Species Survival in the Wild

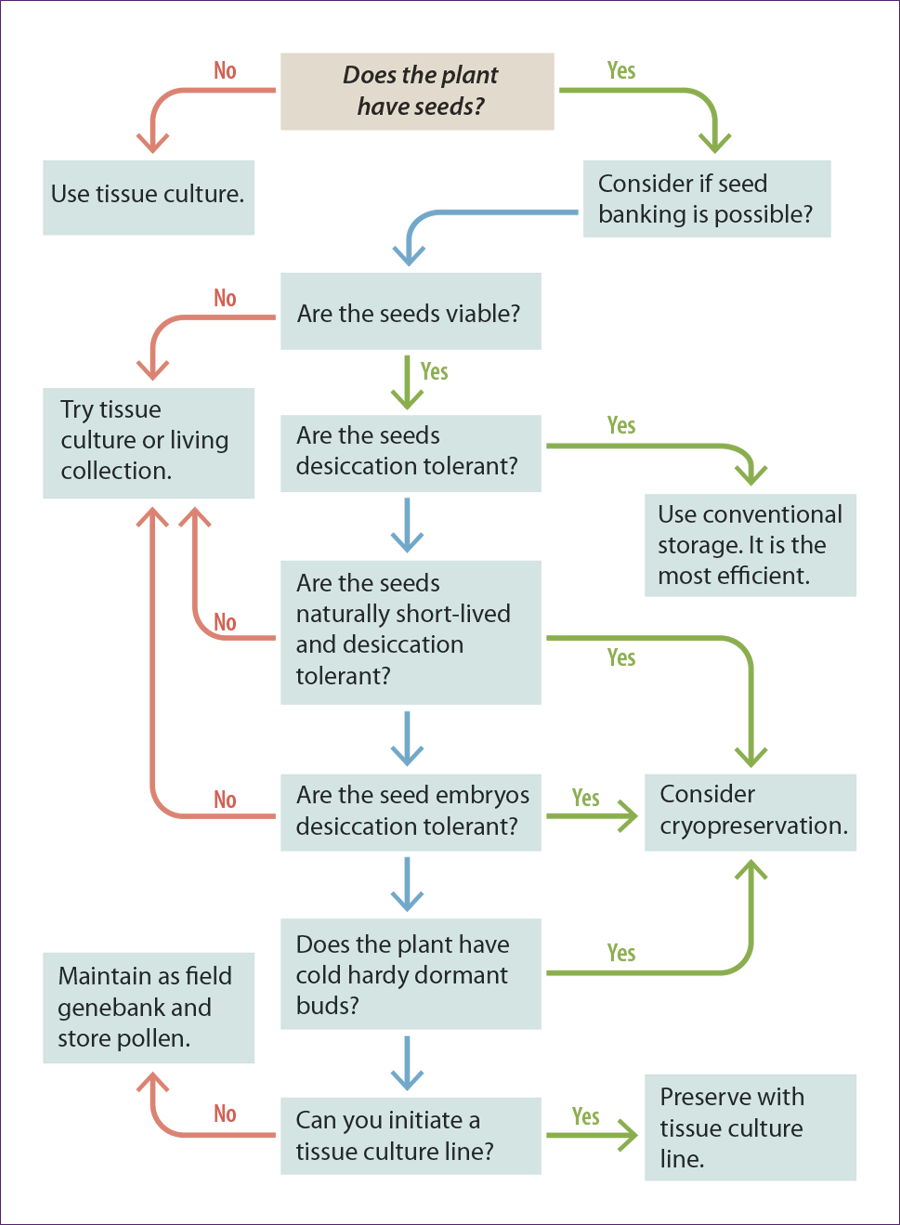

Exceptional plants are those that cannot be conserved long-term using conventional seed banking methods. This includes species with few or no seeds available for banking, species with seeds that are intolerant of desiccation and freezing, or seeds that can tolerate drying, but not freezing, or species that may only tolerate storage at –20°C for less than 10 years.

For ex situ conservation, such species require methods alternative to conventional storage, such as plant cryopreservation and in vitro methods. Many of the world’s plant species may fit these storage categories (see Seaton et al. 2018).

The primary purpose of a conservation collection of an exceptional species is to support the species’ survival and reduce its extinction risk, therefore accurate records of provenance, differentiated maternal lines, and diverse genetic representation are prerequisites.

Plant cryopreservation or tissue culture are alternative storage processes to conventional storage, but these alternatives are only real conservation solutions if the practitioner is able to restore a tissue cultured or cryopreserved plant part back to a rooted plant that is capable of being transplanted into the wild.

As is true for seed research, much more has been done on agricultural or commercially important species than for rare wild species. As more CPC practitioners conduct tissue culture and plant cryopreservation research, the more will be known about the specific needs of rare species and the more possible it will be to examine patterns.

At this stage in the development of the science, we provide recommendations based upon FAO guidelines and recent research noting that a large difference between these bodies of research stems from the fact that because our species are rare, we usually have few propagules to initiate studies, and we are thrilled to have any survival!

Space and staffing capacity will always impact an institution’s conservation program. Exceptional species require a greater commitment of staff time, specialized expertise of staff, and greater infrastructure than conventional seed banking.

In this light, we encourage practitioners to reach out to the experienced in vitro (tissue culture) and plant cryopreservation specialists in the CPC network if they are planning to create internal programs or if they desire to collaborate on research projects for exceptional species.

Several authors have examined patterns in seed storage behavior (see references) that can help collectors. Begin with a literature review to check if any previous research has been done on your taxon. You can check congeners, but beware that this is not always reliable or conclusive.

Our Hawaiian colleagues have found quite varying storage behavior within a single genus (Walters, Weisenberger and Clark, personal communications). Many factors determine variation in seed tolerance to desiccation or freezing. The following are some general patterns observed in seeds that tend to withstand orthodox storage or not.

| Trait | Likely to Be Orthodox (Desiccation and Freezing Tolerant) |

Questionable Tolerance to Orthodox Storage |

|---|---|---|

| Habitat | Arid is especially likely; If it is not growing in a wetland, it is likely | Wetland, riparian |

| Conditions in nature | Seeds normally experience dry down and/or hard freezes | Seeds normally remain moist and do not experience hard freezes |

| Season of seed production | Not spring | Spring |

| Life form | Not tree | Trees |

| Seed bank | Persistent | Not persistent |

| Dormancy | With dormancy | No dormancy |

| Seed moisture content at time of maturation | Dry when it is naturally shed from plant | High (30%–70%) |

| Seed size | Very large (avocado seeds aren't desiccation tolerant) or very small (orchid seeds and fern spores require storage in liquid nitrogen) |

| Plant Groups with High Proportion of Desiccation Sensitive Seeds | Plant Groups with Predominantly Orthodox Seeds |

|---|---|

| ANITAGrade, Arecales, Ericales, Fagales, Icacinales, Laurales, Magnoliales, Malpighiales, Myrtales, Orchidaceae, Oxalidales, Santalales, Salicaceae, Sapindale | Solanaceae, Poaceae, Asteraceae, Brassicaceae |

While collecting, do no harm to the collecting site or the rare population.

If they exist, seek to capture at least five populations of a species across space and time. See “Collecting Seeds from Wild Rare Plant Populations.”

At the seed bank or cryopreservation laboratory, follow steps for each material type to maximize its survival.

Maintain maternal lines for any of these procedures. For highest conservation value, maintain material in a form that will allow for recovery of whole plants that can be used for reintroduction to the wild.

| Stage | Operations | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Establish and stabilize | Handle and pre-select target plants to reduce the potential of microbial contamination. Choose explant type: shoot tips, flower buds, axillary buds, leaves, or embryos. Stimulate axillary or adventitious shoot formation on appropriate medium. | Pretreat explants to prevent browning. Examine microbial colonies to determine if contamination is coming from fungi or bacteria living within plant tissues or from agar surface that was not effectively sterilized. |

| 2. Multiply shoots | Divide the multi-branched explant. Place small shoots onto new media with hormones to stimulate more shoot development. | Check for contamination. |

| 3. Roots form | Induce rooting by transferring well-developed shoots to media containing auxins. | Plantlets are less susceptible to accidental microbial contamination at this stage. |

| 4. Acclimate | Deflask rooted plantlets and acclimatize to greenhouse conditions. | Remove agar from roots. Use pasteurized potting mix to remove a potential source of contamination. |

Figure 2.3 – In vitro and Plant Cryopreservation. From in vitro donor plants, shoot tips can be excised, sterilized, and placed onto a sterile nutrient medium. Application of cytokinin will encourage multiple shoots to grow. With the proliferated shoots, tests of plant cell cryopreservation can ensue options.

Shoot tips are placed onto a high sucrose solution for osmoprotection, followed by immersion, incubation, or exposure to a cryoprotectant solution (depicted is encapsulation dehydration), exposed to liquid nitrogen, and then stored. Experimental steps along the process are advised for species with unknown plant cryopreservation tolerance.

Experimental components may include molarity of osmoprotection solution, type of and duration of exposure to the cryoprotectant, the rate and duration of exposure to liquid nitrogen, and the duration of long-term storage. After storage, tips are warmed and recovered using in vitro methods.

Duplicate accessions to maintain in one or more than one living collection (Fant et al. 2016).

Batty, A. L., K. W. Dixon, M. C. Brundrett, and K. Sivasithamparam. 2002. Orchid conservation and mycorrhizal associations in K. Sivasithamparam, K. W. Dixon, and R. L. Barrett, editors. Microorganisms in plant conservation and biodiversity. Kluwer Academic Publishers, London.

Ballesteros, D., and V. C. Pence. 2017. Survival and death of seeds during liquid nitrogen storage: a case study of seeds with short lifespans. CryoLetters 38:278–289.

Bunn, E., and B. Tan. 2002. Microbial contaminants in plant tissue culture propagation in K. Sivasithamparam, K. W. Dixon, and R. L. Barrett, editors. Microorganisms in plant conservation and biodiversity. Kluwer Academic Publishers, London.

Exceptional Plant Conservation Network, accessed May 29, 2018

Fant, J. B., K. Havens, A. T. Kramer, S. K. Walsh, T. Callicrate, R. C. Lacy, M. Maunder, A. Hird Meyer, P. P. Smith. 2016. What to do when we can’t bank on seeds: what botanic gardens can learn from the zoo community about conserving plants in living collections. American Journal of Botany 103: 1–3.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) 2014. Genebank standards for plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. Rome, Italy.

Fernandez, H., A. Kumar, and M. A. Revilla, editors. 2011. Working with ferns. Springer, New York.

George, E. F. 1993. Plant propagation by tissue culture. Part 1: the technology. Edington, England, Exegetics Ltd.

George, E. F. 1996. Plant Propagation by tissue culture Part 2: in practice. Edington, England, Exegetics Ltd.

Griffth, M.P., M. Calonje, A. W. Meerow, F. Tut, A.T. Kramer, A. Hird, T.M. Magellan, and C.E. Husby. 2015. Can a botanic garden cycad collection capture the genetic diversity in a wild population. International Journal of Plant Sciences176: 1-10.

Panis, B., B. Piette, and R. Swennen. 2005. Droplet vitrification of apical meristems: a cryopreservation protocol applicable to all Musaceae. Plant Science 168:45–55.

Pence, V. C. 2011. Evaluating costs for the “in vitro” propagation and preservation of endangered plants. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology – Plant 47:176–187.

Pence, V. C., J. A. Sandoval, V. M. Villalobos, and F. Engelmann, editors. 2002. In vitro collecting techniques for germplasmconservation. IPGRI Technical Bulletin No. 7. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy.

Reed, B. M., S. Wada, J. DeNoma, and R. P. Niedz. 2013. Mineral nutrition influences physiological responses of pear in vitro. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology – Plant 49:699–709.

Reed, B. M., editor. 2008. Plant cryopreservation: a practical guide. Springer, New York.

Saad A. I. M. and A. M. Elshahed 2012. Plant Tissue Culture Media in Recent Advances in Plant in vitro Culture, accessed May 29, 2018.

Sakai, A., D. Hirai, and T. Niino. 2008. Development of PVS-based vitrification and encapsulation – vitrification protocols. Pages 33–57 in Reed, B. M., editor. Plant cryopreservation: a practical guide. Springer, New York.

Seaton P.T., S.T Hosomi., C.C., Custódio, T.R. Marks, N.B. Machado-Neto, and H.W. Pritchard. 2018. Orchid Seed and Pollen: A Toolkit for Long-Term Storage, Viability Assessment and Conservation. In: Y.I. Lee and E.T. Yeung (eds) Orchid Propagation: From Laboratories to Greenhouses—Methods and Protocols. Springer Protocols Handbooks. Humana Press, New York, NY