Save Plants

Center for Plant Conservation

Plant conservation has seen remarkable advances in the last decade through the integration of technology and innovation, which have proven instrumental in preserving rare and endangered flora. One significant example of this, featured in this month’s newsletter, is the California Native Plant Society’s Rare Plant Inventory—a fully integrated web application that provides assessments of the current conservation status of the state’s rare and endangered plant species, contributing to effective conservation planning and prioritization.

In addition to technological solutions, novel strategies borne of human ingenuity are redefining conservation methodologies. Desert Botanical Garden, for instance, has adopted a unique approach by training scent detection dogs to identify and locate rare plants in their natural habitats, supplementing traditional field survey techniques. These dogs are so good that they often locate hard-to-find rare plants that their human colleagues can’t spot. Similarly, Meg Engelhardt of Missouri Botanical Garden, our August Conservation Champion, shares how she and her colleagues have innovatively employed X-ray technology to assess the viability of seeds stored in their seed bank, facilitating improved management and utilization of these crucial genetic resources.

This fusion of technology and creativity is carving a new path towards robust and holistic plant conservation strategies, ensuring the survival and longevity of our world’s rare and treasured plant species. We hope that you feel as inspired as we do by these stories and continue your support of our conservation heroes and their extraordinary work.

Sincerely,

Powerful New Tools to Prioritize California Rare Plant Conservation

California is well known as a global biodiversity hotspot, spanning several major bioregions. While a majority of the state sits within the California Floristic Province – one of five Mediterranean climate regions of the world – California also spans portions of the Sonoran, Mojave, and Great Basin Deserts. It’s no wonder that the California flora is so striking for its diversity and richness, with over 6,600 unique native plant taxa! More than one-third of this diverse flora is endemic to the state (occurring nowhere else), and over one-third is also considered rare or endangered. Evaluating and ranking the rarity of these native plants enables us to focus conservation resources where they are needed — and for more than 55 years, the California Native Plant Society’s Rare Plant Program has done just that.

To track California’s rare plants, the Rare Plant Program developed what is now called the CNPS Rare Plant Inventory (RPI). The RPI includes rarity ranks, threats, location information, and habitat data. It began as a collection of index cards, which developed into a series of published print manuals and now exists as a publicly accessible online database. Modernization of this database over time has been crucial for maintaining and continuously updating population records, ever-changing taxonomy, the latest research, and new threats to California’s rare plants. “The RPI is such a critical conservation tool, helping identify plant species that should become listed under the Endangered Species Act, or preventing them from becoming extinct by identifying at-risk species and prioritizing conservation actions,” said Aaron Sims, Rare Plant Program Director at the California Native Plant Society. CNPS collaborates closely with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s California Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB), which maintains its own database (RareFind) of detailed location information for all the plants included in the RPI.

Although the CNDDB and CNPS teams share data, these databases are used differently. The CNPS RPI is open access and obscures location data to the level of 7.5-minute quadrangles (an area of roughly 50-60 square miles) to protect the rare plants from poachers. Within the inventory, each plant has a page that provides a snapshot of important information, such as scientific name, common name, rarity rankings, distribution, habitat, and threats. Many pages feature plant photos and links to more detailed taxonomic or natural history information. Simple and advanced search functions are available. Users – including federal agency partners, academics, conservationists, and the general public – can search the inventory to find out what rare plants occur in a particular quad or geographic area, or for plants that are exposed to particular types of threats (such as development, mining, or poaching). The pages also have information on how many of the plant occurrences are recent (seen within the past 20 years) or historical (not seen in the past 20 years). Rare plant populations that have not been seen and documented for 20 years or more are prioritized for field surveys to determine if the population is stable and whether it is facing new or increased threats.

Recent advancements in functionality of the RPI include automated filtering tools that allow professionals to acquire a list of priority rare plant species quickly and easily. This filtering function creates data output that automatically identifies:

- Species with occurrences that are 90-100% historical

- Species that have only One Known Occurrence (OKO) in the entire world

- Species that might need to have their conservation ranking changed, based on number of occurrences and documented threats

With such a large database and the vast geographic area of California, this functionality in the RPI is an essential tool to help professionals identify and update the highest conservation priorities – in other words, where our limited time and conservation dollars are most needed!

-

Display of newly available threat data in the RPI for Trifolium hydrophilum, indicating nearly half of its occurrences are threatened (46%) and that development is the largest documented threat to this species. Courtesy of the California Native Plant Society. -

Trifolium hydrophilum – southern-most population which had a banner year after several very bad years which led to concern of local extirpation; population data was updated and it was seed banked this year. Photo credit: Kristen Nelson. -

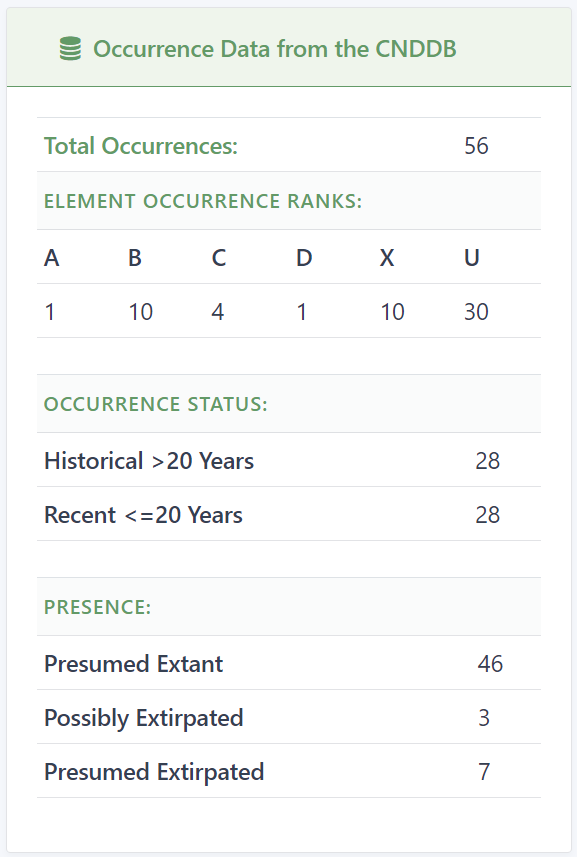

Occurrence statistics for Trifolium hydrophilum. Here we can see that half of its occurrences are historical (over 20 years old), with 10 occurrences being possibly or presumed extirpated. Courtesy of the California Native Plant Society.

When plans were being developed for the 2023 field season, data from the RPI enabled researchers to identify the Santa Ynez groundstar (Ancistrocarphus keilii) as a key conservation priority. Two reasons stood out: this species is known from only a single, small occurrence (one patch of ground in the entire world); and that lone occurrence had not been documented in almost 30 years. Without field work and data collection to update the Santa Ynez groundstar’s record for this population, we were lacking critical information about its status and potential conservation needs.

A successful expedition to find and document the Santa Ynez groundstar soon followed. A collaborative group of botanists from Santa Barbara Botanic Garden and CNPS collected new voucher specimens, completed conservation seed banking, acquired the first-ever photos of this plant in living condition, and collected detailed data about the status of the population and its habitat. News of the expedition and its “rediscovery” of this diminutive species made headlines! “Building off the excitement of a superbloom year in California, and being able to share striking photos of this plant that hadn’t been seen in decades, helped this story go viral and drew much-need attention to the importance of plant conservation,” shared Sims.

This conservation success story was made possible with the CNPS Rare Plant Inventory, paving the way for even more of California’s vulnerable flora to be identified, prioritized, and preserved for future generations.

-

Phacelia exilis in the Santa Clara River (Utom) watershed. Photo credit: Jordan Collins. -

Jordan Collins collecting population and habitat data for a historic population of Caulanthus californicus, which CNPS updated this year. Photo credit: Kristen Nelson. -

Monolopia congdonii in Carrizo Plain National Monument. Photo credit: Kristen Nelson.

Man's Best Friend Helps Find Elusive Endangered Orchid

Dogs are known for their powerful olfactory senses and have been used by humans over the years to detect objects from drugs to electronics to truffles. This sensory superpower makes them the star of a captivating project at Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix, AZ, posing the question: can canines be used to locate hard-to-find or dormant rare plants? Could dogs actually help conservationists monitor and locate rare plant populations that have not been observed in recent years or are considered historic? To begin to answer these questions, detection dogs at Desert Botanical Garden were tasked with finding a rare endemic orchid, Spiranthes delitescens (Canelo Hills ladies’ tresses orchid), with a challenging twist — the plants are so rare that no samples were available to train the dogs’ noses on!

Instead, scientists at Desert Botanical Garden trained the dogs on a closely related species from southern Nevada called Spiranthes infernalis (Ash Meadows ladies’ tresses) – infernalis (“from hell” in Latin) because it grows just outside of Death Valley. Ten plants were brought from Nevada to California so that Lauralea Oliver of K9inscentive could train the dogs at their facility. Because the two species are in the same genus, scientists hoped (but weren’t entirely sure) that their scent signatures would be similar enough that the dogs would be able to detect both. When the dogs could successfully find the Ash Meadows orchid at the training facility, it was time to take them to Southern Arizona to search for the elusive Canelo Hills orchid.

The trip was nerve-wracking. Would the Canelo Hills orchids smell similar enough to the species the dogs were trained on? Would the dogs be able to take the success they had in a controlled off-site environment and replicate it in the wild? In thick vegetation containing dozens of other plant species, along with all the other scents found in nature, the canine noses would be put to a true test. To everyone’s relief, the dogs were successful! Not only did they find Canelo Hills orchids that were in flower, they were also able to find plants that had barely emerged an inch from the soil. The scientists actually had to get on hands and knees to find what the dogs were alerting them to. The next step for the dogs will be a trip to two historic sites where the rare orchids haven’t been seen in decades, to find out if their monumental orchid-sniffing success can be replicated in an uncertain population.

Conservation of the rare Spiranthes delitescens will be assisted by another grant received by Desert Botanical Garden, supporting the collection of seeds for banking as well as propagation. In situ, orchids require a specialized fungus that assists with seed germination and provides the plant with nutrients.

Without this fungus, in vitro propagation (tissue culture) is necessary for the plant to reproduce. This method requires the use of specially formulated media to provide the nutrients the fungus would otherwise provide. Desert Botanical Garden scientists have now worked out the protocols for growing Canelo Hills orchid plants in culture and will move to propagating them ex vitro, using media inoculated with its associated fungus.

This work has benefited from collaboration with researchers at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) and North American Orchid Conservation Center (NAOCC), who have been identifying and culturing the fungus using orchid roots provided to them by Desert Botanical Garden. NAOCC and SERC have since sent back samples of the fungus, which will be grown and used to inoculate the soil mix. The end goal of this project is to be able to produce hundreds — if not thousands — of Canelo Hills orchid plants, which will then be used in reintroduction projects in suitably restored habitat where they once occurred.

Learn more about Spiranthes delitescens conservation and the orchid detection canines in Steve Blackwell’s 2023 National Meeting presentation .

-

Working dogs sometimes need a short break! Detection dog Muon is being carried by a human member of the team. Photo by Eirini Pajak. -

Steve Blackwell of Desert Botanical Garden collecting seed from Spiranthes delitescens found by detection dogs in the wild. Photo by Eirini Pajak. -

Desert Botanical Garden team searching for Spiranthes delitescens with detection dogs. Photo by Eirini Pajak.

Meg Engelhardt

Our August Conservation Champion, Meg Engelhardt, brings both an innovative and dedicated approach to rare plant conservation. As Seed Bank Manager of the Missouri Botanical Garden, Meg integrates technology and out-of-the-box thinking with established conservation best practices to safeguard the rare plants in her care. By utilizing x-ray imagery to examine seed quality, Meg and her team are able to see exactly how many healthy seeds are available and make informed decisions about how to best use them–saving precious time and resources. We are fortunate to count Meg as a partner in our shared mission to Save Plants from extinction. As she states, “whether you are new to plant conservation or it has been your lifetime career, we all have so much to learn from each other.”

When did you first fall in love with plants?

Despite growing up in an urban area, I always had a special fondness for exploring wild landscapes. It is hard to pinpoint the exact moment that I fell in love, but the ‘seed’ was likely planted somewhere between hiking through the forests at Girl Scout Camp, smelling the gardenias in my grandpa’s garden, and seeing the film FernGully on the big screen as a child. That seed became deeply rooted during my participation in the Ecological Restoration Corps, a high school summer internship program through the Missouri Botanical Garden.

What was your career path to Missouri Botanical Garden?

While studying music at Millikin University, a scheduling fluke put me in the biology major’s first-year course, taught by Dr. Judy Parrish, a plant ecologist. I was hooked! I then took all the core biology classes and plant classes and served as her TA and undergraduate research fellow. I still earned that music degree but went on to earn my master’s degree in Conservation Biology with Dr. Roger Anderson at Illinois State University, where I studied invasive plant species phenology. After spending a summer surveying forest vegetation deep in the Missouri Ozarks, I spent several years identifying new high-quality natural communities for the Illinois Natural Areas Inventory Update. From there, I stayed on staff at the Illinois Natural History Survey as part of their wetland delineation team. Eventually, I was ready to take on a role where I could have a stronger impact in plant conservation. I was so happy to return to my hometown of St. Louis in 2014 when I took the position of Seed Bank Manager at the Missouri Botanical Garden.

In your experience, what are some of the pressing conservation needs impacting Missouri’s rare and native plants?

With climate change rapidly exacerbating habitat degradation, the pressure to understand and conserve our natural environment is greater than ever. Cooperation and communication between researchers, practitioners, and policy makers is critical, but there are many challenges to effective collaboration. Key issues include inconsistent taxonomic designations, incompatible databases, and limited staffing. Prioritizing development of modern methods and technologies may be crucial to alleviating some of these challenges, creating smoother collaboration to achieve conservation goals.

What conservation project(s) are you currently working on? What successes or challenges have you encountered in your work?

In addition to seed banking species of global, national, and regional conservation concern, I have been collecting and banking seeds from the 2,200+ species native to the state of Missouri. One problem we discovered along the way is that we have not always had a good understanding of the quality or viability of our seed collections—occasionally resulting in misspent time and resources. Taking the time to thoroughly test these collections back in the lab has resulted in better use of limited natural and economic resources, as well as increased success in subsequent collection attempts.

How does technology impact and advance your work in seed bank management?

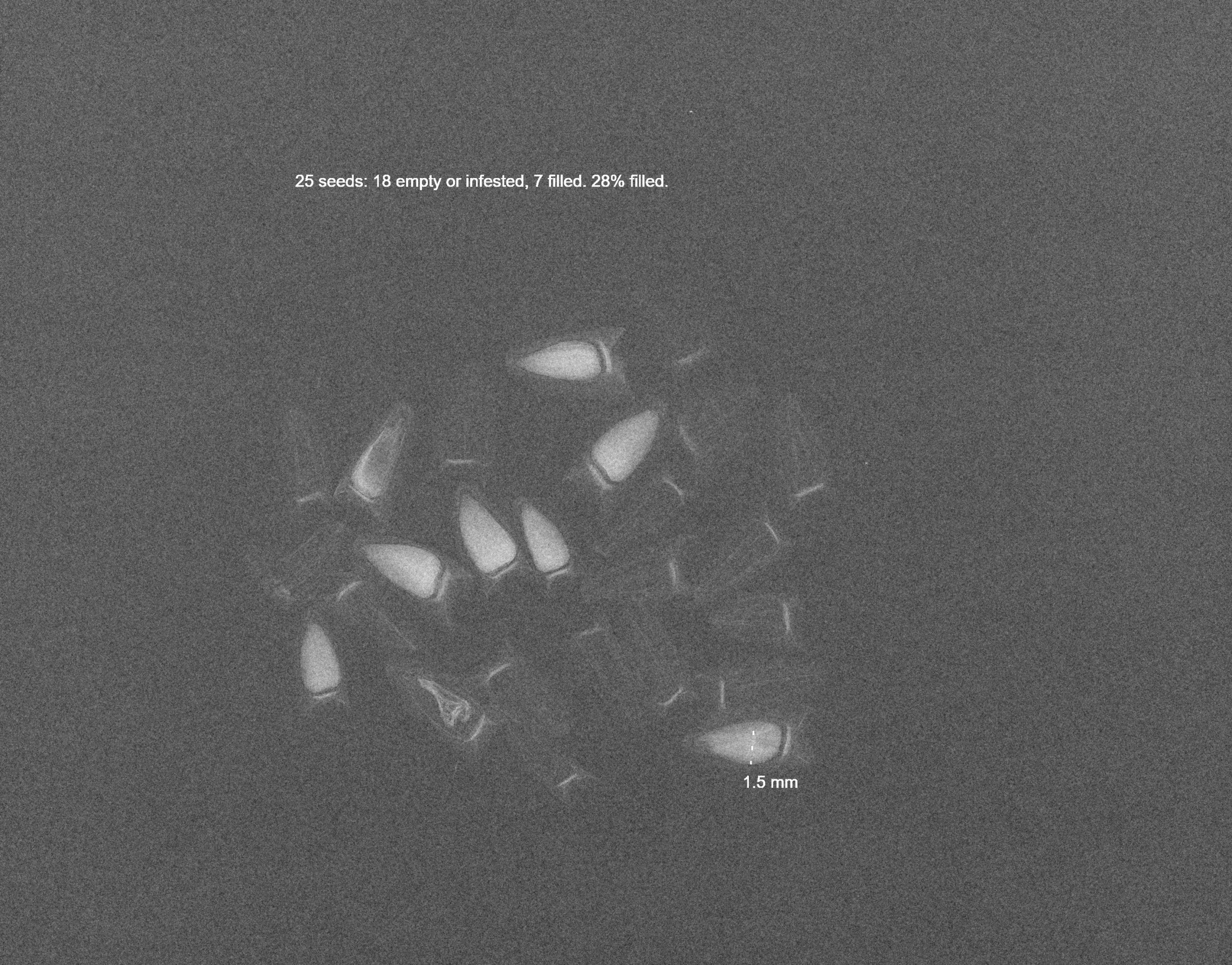

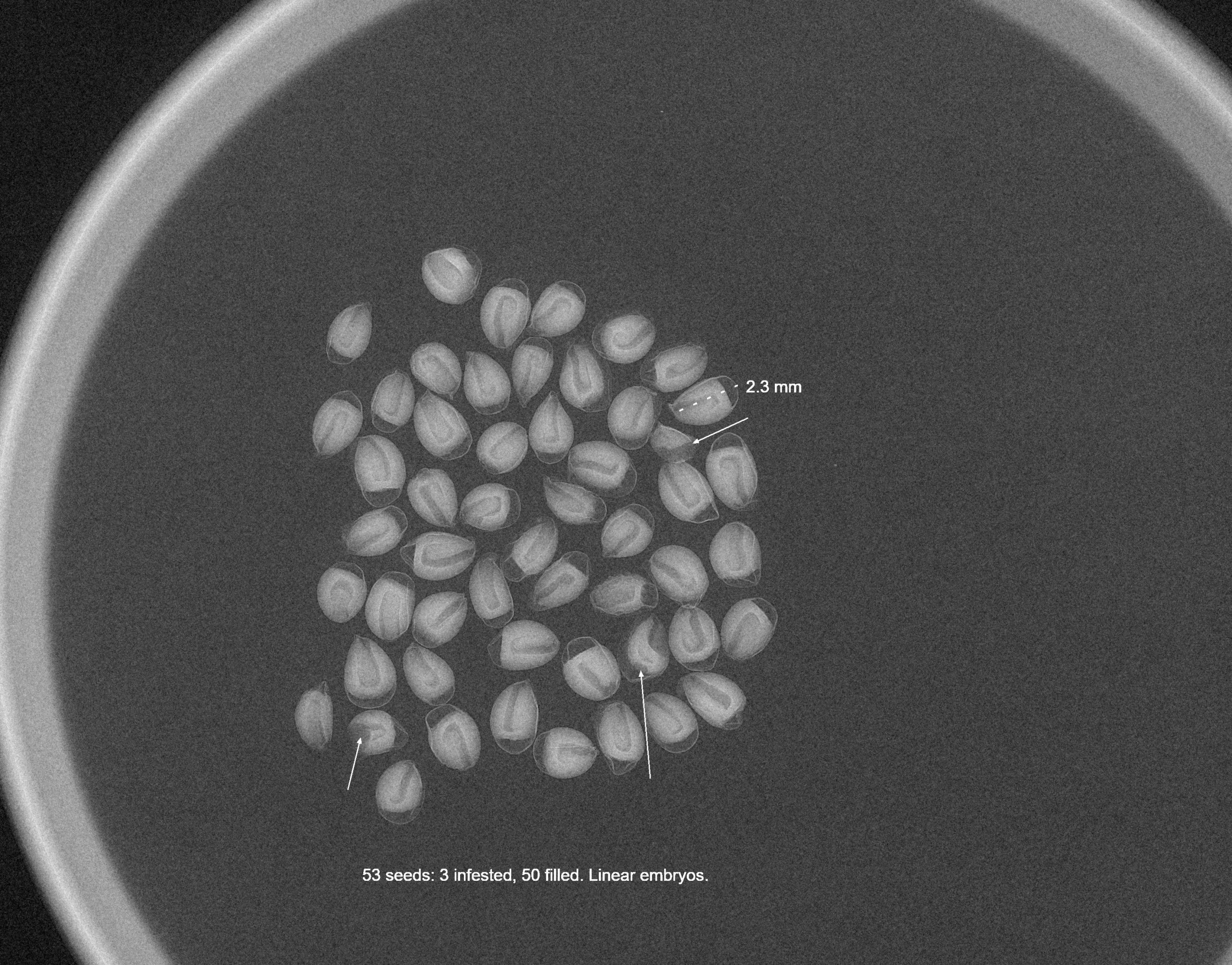

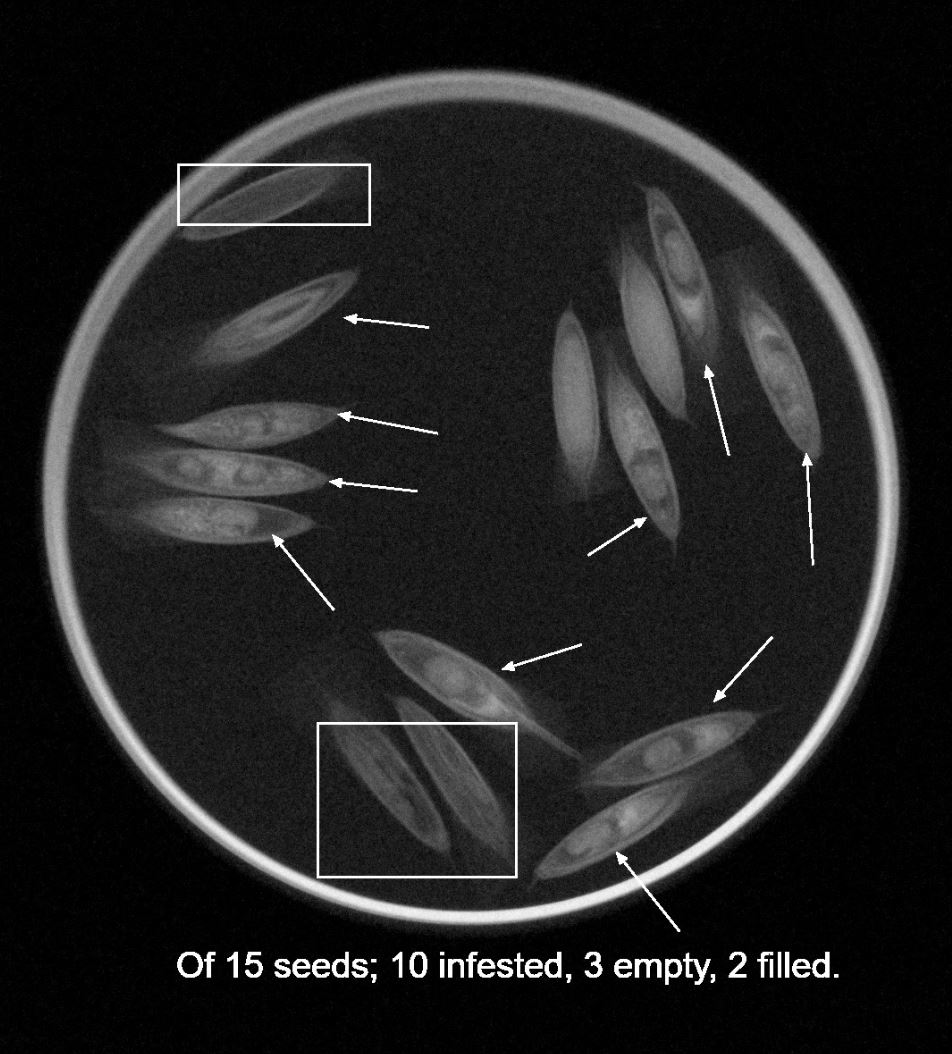

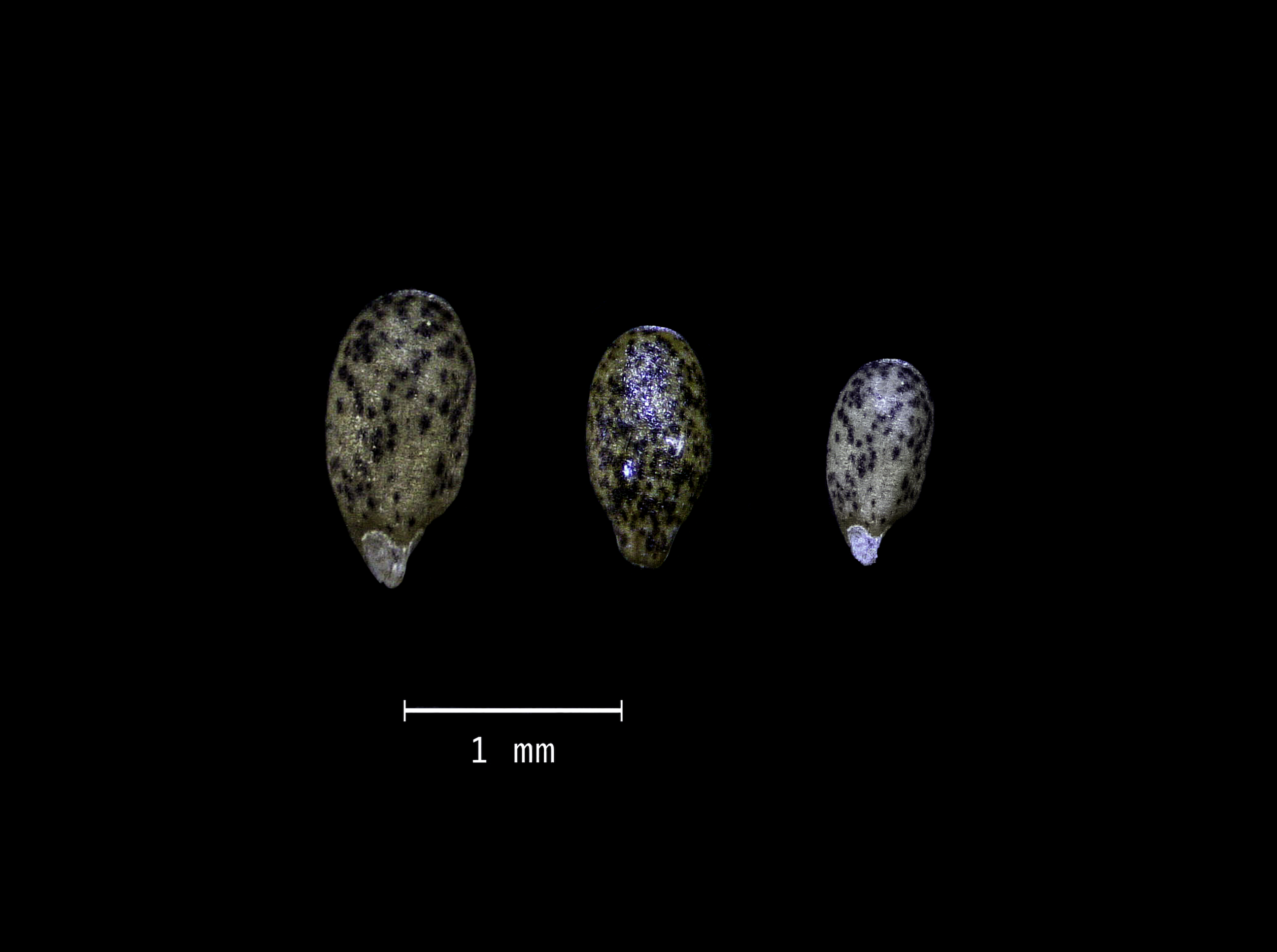

Knowing exactly how many healthy seeds we have available is critical to making decisions about how to best use them. Inspection by cut tests involves dissecting seeds to visually evaluate development of inner tissues. Yet this method, while effective, is destructive and inappropriate for small collections of highly sensitive, rare species. As an alternative, x-ray imagery of a seed sample allows visual inspection of seed quality without incurring damage. Seeds are categorized as full (healthy), empty, insect-infested, or underdeveloped. After seeing seed x-ray machines in action at Chicago Botanic Garden, Bend Seed Extractory, and Millennium Seed Bank, I knew this was the next step we needed to take in our own seed bank. Using x-ray imagery to examine seed quality has been a game changer in our ability to understand the quality of our collections.

What has surprised you about working with and learning more about rare plants?

I was pleasantly surprised to find out that most of our seed collections are of acceptable quality and viability, despite varied collection and management histories. Of the 2,400 collections that have been x-rayed to examine seed fill, only 39 collections (1.6%) were found to have no filled seeds. Encouragingly, about one-third of all collections examined have seeds that are 100% filled, giving us a good understanding of the resources available for potential research and reintroduction projects to support these species in the wild.

What advice would you give to those who wish to learn more about how they can help save imperiled plant species?

Whether you are new to plant conservation or it has been your lifetime career, we all have so much to learn from each other. I would recommend prioritizing opportunities to interact with other people and organizations to learn about their experiences, needs, challenges, and successes. I am grateful for organizations like the Center for Plant Conservation, which provide a hub for sharing knowledge in support of rare plant conservation.

Learn more about the Missouri Botanical Garden Seed Bank’s seed quality and viability testing of CPC National Collection species in Meg Engelhardt’s 2023 National Meeting presentation.

A Big Win for Small Seeds!

Rare plant seeds are a precious resource that provide the basis for recovery of these plants in nature. Yet rare plant seed collections often contain too few seeds to be utilized for reintroductions without seed augmentation. “Seed bulking” is the process of growing plants from seed to reproduction in a botanic garden setting to increase seed available for restoration. While necessary, it can impose unnatural filters on the genetics of rare plant populations — and we know little about how growing a plant outside its native range affects plant health or genetic filtering.

The Center for Plant Conservation (CPC) is pleased to announce that we have been awarded a three-year $589,833 National Leadership Grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services to better understand the critical practice of seed bulking. The grant was submitted in collaboration with seven members of the California Plant Rescue network, including co-Principal Investigators Christa Horn (San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance) and Carrie Kiel and Naomi Fraga (California Botanic Garden). We will leverage the propagation expertise and infrastructure of partners throughout the California Plant Rescue network to seed bulk 15 rare annual California native plant species, including in-depth tracking of propagation techniques and maternal line survival over two growing seasons in two locations (inside and outside of their home range).

The project will also evaluate how seed bulking influences the genetics of two rare California annuals in the CPC National Collection: Saltmarsh Bird’s beak (Chloropyron maritimum ssp. maritimum) and San Diego thornmint (Acanthomintha ilicifolia). These insights, together with insights from our broader network, will be used to create CPC Best Practices Guidelines for Seed Bulking and improve the quality of curation for rare plants more broadly.

National Collection Spotlight: Aboriginal Prickly-apple

Aboriginal Prickly-apple (Harrisia aboriginum) is a critically imperiled species endemic to the western coast of Florida. There are 12 known extant occurrences of this rare species, and it is listed as Endangered under the federal Endangered Species Act. Like many plants in South Florida, this species is threatened by invasive species and habitat loss/fragmentation. This rare cactus also faces the major threat of poaching from its wild populations for illegal horticultural collection.

Harrisia aboriginum is secured in the CPC National Collection at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Naples Botanical Garden, and Marie Selby Botanical Gardens. At Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, this species has been held in conservation collection as part of the CPC National Collection for over 30 years.

Learn more about conservation actions taken for Aboriginal Prickly-apple on its National Collection Plant Profile, and help support critical conservation work for this species with a Plant Sponsorship.

As Seen on CPC’s Rare Plant Academy: 2023 CPC National Meeting on RPA’s Conference Recordings

The Rare Plant Academy Video Library hosts many recordings of recent conferences, including this year’s CPC National Meeting. Recordings of presentations from our 2023 National Meeting are now available for viewing on the Rare Plant Academy website. Our 2023 meeting was themed “On the Horizon: Looking to the Future of Plant Conservation,” with presentations ranging from progress in growing conservation programs to goals and the future trajectory of rare plant ex situ conservation. Wendy Hodgson of Desert Botanical Garden delved into the role of agaves in the cultures of Indigenous Peoples north of the U.S.-Mexico border in her Keynote Address, “Agaves and Humans—An Affair for the Ages.” View dozens of presentations encompassing both recorded in-person talks and pre-recorded online-only talks on the RPA Video Library now!

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Employment Opportunities

Responsible for the leadership and effectiveness of the Southeastern Center for Conservation (SECC) Research team, which produces world-class scientific research with important practical applications to advance plant conservation. Provide strategic leadership, in cooperation with the Vice President of Conservation & Research and Director of Applied Conservation, to set and meet program objectives and priorities. The mission of the SECC is to lead innovative strategies and partnerships to conserve imperiled plants and natural communities.

Salary: $95k-110k

For more information and applications please go to Atlanta Botanical Garden’s website.

https://recruiting.paylocity.com/Recruiting/Jobs/Details/1854976

Lyon Arboretum at the University of Hawaiʻi is searching for a Director for the Hawaiian Rare Plant Program. The position is for a tenure-track, open-rank, faculty specialist. A brief description is posted below, and full details can be found here.

The Lyon Arboretum is an Organized Research Unit at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Lyon’s Hawaiian Rare Plant Program (HRPP) is a research and gene bank curatorial program that serves as the primary ex situ native Hawaiian plant germplasm repository for the State of Hawai’i, and represents one of the major means by which the Lyon Arboretum contributes to plant conservation. The mission of the HRPP is to prevent further extinction of native Hawaiian plant species and Polynesian introduced crop plants, to propagate plants for approved restoration projects and garden use, and to initiate and maintain an ex situ germplasm collection of the “critically endangered” Hawaiian plants. The HRPP works cooperatively, in joint conservation efforts with other botanical gardens, various state and federal agencies, and other environmental conservation organizations and land managers. The HRPP Seed, Micropropagation, and Cryopreservation Conservation Laboratories collectively bank >33 million seeds, and >43,000 in-vitro living plant collections, representing >600 native Hawaiian plant taxa. For more information about the program, refer to: https://manoa.hawaii.edu/lyon/research/hrpp/

Please contact Don Drake (dondrake@hawaii.edu) if you have any questions about the position.

Ways to Help CPC

Conservation Advocacy Initiatives

The Extinction Prevention Act of 2023 seeks to create dedicated funds to conserve butterflies in North America, plants in the Pacific Islands, freshwater mussels in the United Sates, and desert fish in the Southwest United States.

The Pacific Islands Plant Conservation Fund Act of 2023 portion of this bill would “support and provide financial resources for projects to conserve such species of plants and the ecosystems of such species of plants and to address other threats to the survival of such species of plants.”

Advocating for native plants is easy, and your help is crucial to Save Plants!

Contact your U.S. Representatives to urge them to vote YES on the Extinction Prevention Act of 2023:

– Go to house.gov/representatives or call the Capitol Switchboard 202-224-3121 and speak to someone in the office of your U.S. Representative.

– Give your name and zip code.

– Give the bill number and name (H.R. 3494 / S. 1708 / Extinction Prevention Act of 2023), and your vote.

Donate to Save Endangered Plants

Without plants, life as we know it would not be possible. Yet two in five of the world’s plants are at risk of extinction. More than ever before, rare plants need our help!

That is why all of us at the Center for Plant Conservation (CPC) are deeply grateful to have you as part of our conservation community. Your generous and unyielding support allows CPC and our network of world-class botanical institutions to make great strides in our shared mission to Save Plants from extinction.

Your gift ensures CPC’s meaningful conservation work will continue. Together, we save more plants than would ever be possible alone—ensuring that both plants and people thrive for generations to come. We are very thankful to for all that you do to help us Save Plants!

Donate to Save Plants Today!

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today