Save Plants

Center for Plant Conservation

North America’s extraordinary tapestry of ecosystems is woven together with threads of captivating species, among which the orchids stand out as some of the most intriguing. These often-overlooked gems sprinkle the continent, from the dense woods of the eastern United States to the arid deserts of the Southwest, to the swampy wetlands and rich network of rivers and streams of the southeastern states, and to the rich orchid floras of islands such as Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the California Channel Islands. Their dazzling diversity—over 210 species in various sizes, shapes, and colors—paints a vibrant picture of North America’s botanical richness.

Beyond their uncontested beauty, orchids have evolved unique and complex relationships with their surroundings. Some have intricate ties with specific insects, while others depend on particular fungi to survive. These delicate symbiotic relationships are touching and endearing examples of the interconnectedness of life.

Yet, the world of North American orchids wouldn’t be as understood and appreciated without the dedication of passionate researchers, conservationists, and enthusiasts. These individuals traverse wild terrains, meticulously documenting species, ensuring their preservation, and unraveling their mysteries. Many among them are driven by a mix of scientific curiosity and a profound respect for nature’s artistry. They understand that conserving these botanical wonders isn’t just about saving a plant—it’s about preserving the intricate web of life they represent.

In this issue, we delve into the work of Atlanta Botanical Garden’s work with the white fringeless orchid (Platanthera integrilabia), a listed species under the US’s Endangered Species Act. We also provide an insider’s look into the Orchid Greenhouse of the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance in San Diego, where hundreds of species, many of which were the product of confiscations from poachers, found a safe and comfortable resting place to be admired and studied under the caring and skilled hands of the Zoo’s horticultural team. We also celebrate the work of Dr. Peter Zale of Longwood Gardens, our October 2023 Conservation Champion, through a delightfully personal interview. Also included in this issue is a feature on the critical and wide-ranging work of the North American Orchid Conservation Center.

Individuals, organizations, and grassroots movements are pivotal in the role of saviors of orchids and other plants, creating awareness, fostering appreciation, and championing conservation efforts. Their work, intertwined with the beauty and intricacy of the orchids themselves, reminds us of the wonders in our backyards and the importance of safeguarding them.

Cheers to the world of North American orchids and the people dedicated to preserving and sharing their stories!

Uniting to Save North American Orchids

At the North American Orchid Conservation Center (NAOCC), plants in the Orchidaceae family take center stage. This is one of the largest taxonomic families of plants in the world, comprising more than 28,000 species. While most orchid diversity is in the tropics, the U.S. and Canada are home to over 200 native species—over half of which are considered threatened or endangered in some part of their range. Orchid conservation is therefore a top priority, but it is also a challenge, because orchid ecology is a puzzle. We still have much to learn about orchids’ specific lifecycle needs and their roles in ecosystems before we can assemble the puzzle pieces to achieve sustainable conservation success.

To address this tremendous need for conservation on a national scale, Dennis Whigham, Senior Botanist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), had a vision to connect collaborators across the United States and Canada in a concerted effort to protect and research native orchids. Along with Dennis and Melissa McCormick at SERC, NAOCC’s founding partners included the Smithsonian’s National Zoological Park, the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Gardens, and the U.S. Botanic Garden. The cornerstone of NAOCC’s conservation model is recognizing the power of collaboration. Its network has grown to more than 60 collaborators, all working together on restoration, research, education, and outreach.

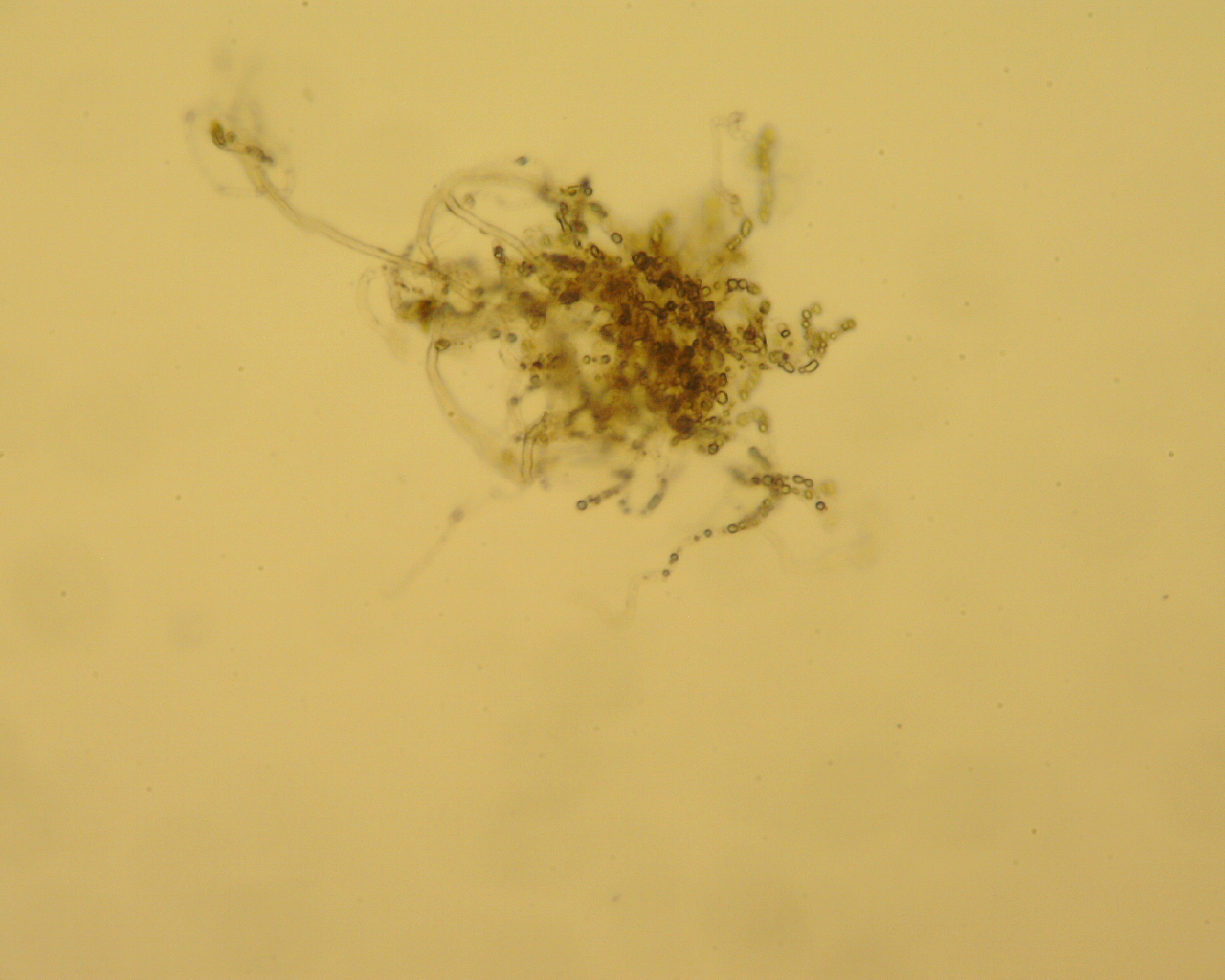

Orchids have a unique relationship with mycorrhizal fungi. Researchers collaborating with NAOCC / SERC aim to unravel the essential roles these fungi play in orchid ecology. Tiny and dust-like orchid seeds contain little nutrition to support embryo growth from germination through the protocorm stage, so seedlings must develop relationships with fungi to sustain growth. NAOCC and its collaborators have found that orchid germination success depends not just on the mere presence of mycorrhizal fungi, but also on what type and quantity of fungi are present! The presence of appropriate fungi in a potential habitat is now understood to be a critical component of successfully establishing sustainable populations. Learning more about the pivotal role of fungi in orchid germination, early growth, and other phases of orchid lifecycles will help contribute to best practice protocols for orchid conservation. NAOCC is therefore paving the way to orchestrate a collective, nation-wide effort to develop propagation protocols for native North American species and establish national and regional centers —much like CPC’s National Collection of Rare and Endangered Plants—to collect orchid seeds and, crucially, the mycorrhizal fungi that the orchids need.

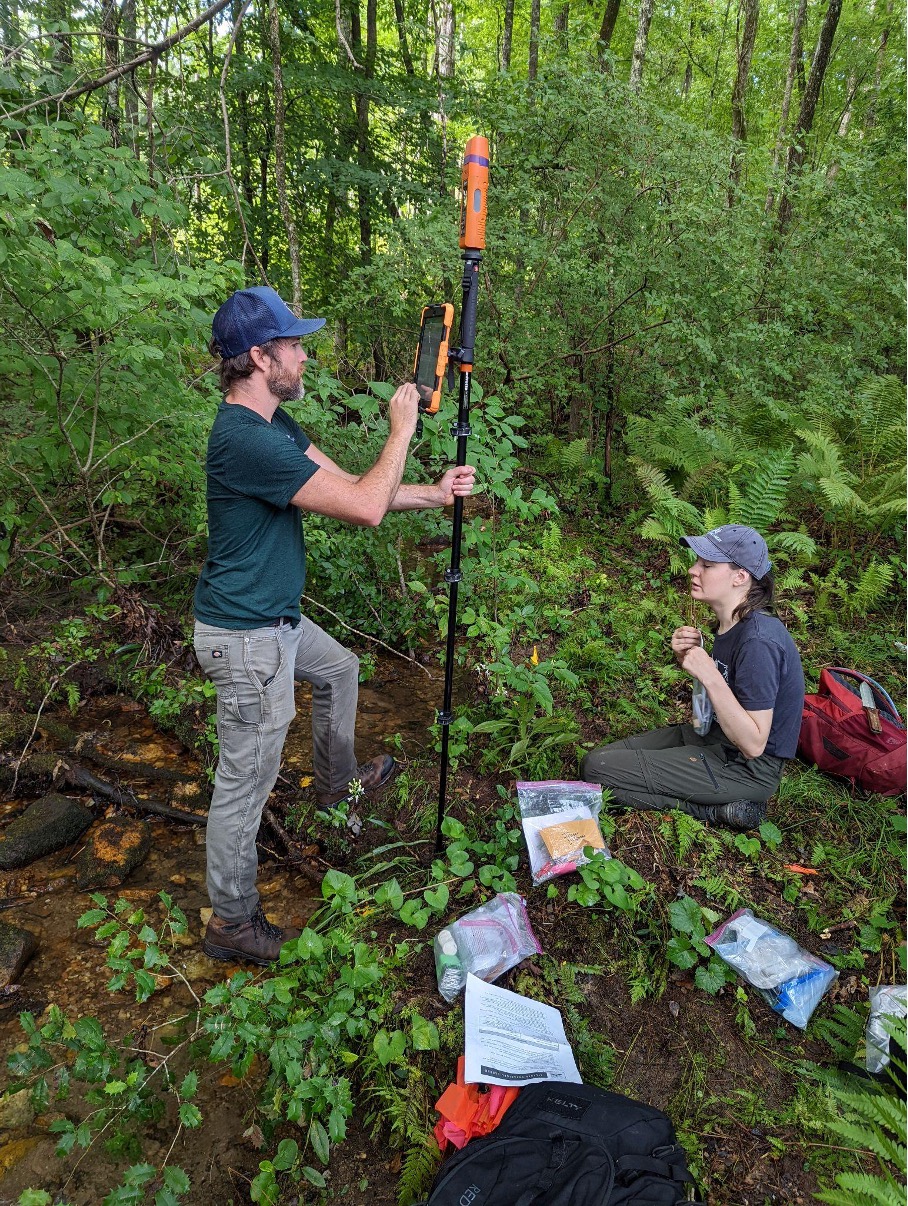

NAOCC is also involved in collaborative projects across the continent focused on in situ conservation of native orchids. Their work with scent detection dogs at the Desert Botanical Garden, where canines were trained to find elusive rare orchids in wild populations in the Southwest, was featured in our August newsletter. A similar project in New Jersey and Virginia has successfully used scent detection dogs to find endangered Isotria medeoloides, often called “the rarest orchid east of the Mississippi.” In 2024, NAOCC will initiate a controlled study to evaluate the efficiency of orchid scent detection dogs at an army base in Virginia, where areas designated for logging will be surveyed for orchids by humans first and then by scent dogs. This study will provide an opportunity to determine if canines are as efficient as humans at detecting Isotria.

In addition to conservation, community outreach and education are pillars of NAOCC’s mission. Citizen science—engaging the public in scientific research—is a key aspect of many NAOCC projects. Understanding native orchid pollination is both an essential piece of the puzzle to ensure effective conservation on an ecosystem scale and a stellar opportunity for citizen science. Almost 50% of North American orchid species have unknown pollinators. Even when pollinators are known, data is typically scarce and only from a few populations. NAOCC / SERC researchers are investigating orchid pollination in several states across the U.S., including Michigan, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Texas, and most of the Atlantic coast, and plan to expand the project nationwide. In one collaboration with graduate students in Virginia and Texas, small motion-capture cameras are set up in orchid populations to record pollinator interactions. This project relies heavily on volunteers to monitor the cameras and populations, offering valuable hands-on experience studying native orchids and contributing to their conservation.

Many people are unaware that North America has native orchids—despite their presence in all U.S. states and Canadian provinces! NAOCC aims to make native orchids and their conservation more accessible and prominent to the general public. In addition to incorporating citizen scientists in research projects, NAOCC conducts outreach in the form of tools like Go Orchids, an easy-to-use interactive online key for identifying native orchids, with a companion print edition field guide in the works. Another innovative outreach tool developed by NAOCC combines art and science to inspire and inform all ages about orchid conservation in the form of origami – or in this case, “orchid-gami.”

And a particularly exemplary outreach program is Orchids in the Classroom, developed with Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, which trains middle school teachers to help students learn how to grow orchids and conduct experiments with them. This program has received an overwhelmingly positive response from educators, students, and outside groups. Orchids in the Classroom will expand to 15 schools in the D.C. metropolitan area in 2024 and go national in 2025, including Alaska, Minnesota, and Delaware. NAOCC hopes to continue its expansion of this exciting program, inspiring students nationwide to learn about orchid conservation.

Collaboration empowers any conservation effort—a sentiment embodied by NAOCC in its approach to saving our native orchids. While NAOCC focuses its work on North American species, its model has made waves in orchid conservation on a global level. NAOCC’s expertise has led to a partnership with the U.S. Forest Service’s Institute of Pacific Islands Forestry to better understand and protect native orchids in Palau, with a key emphasis on involving Palauan community members in the project. The NAOCC model has also received recognition in Europe through the European Orchid Conservation Center and the Interactive Conservation platform for Orchids Native to Greece/Turkey.

Before NAOCC’s formation, no national organization or collective effort was explicitly aimed at orchid conservation on a continental scale. Ten years after its formation, NAOCC continues to expand and pave the way for a cohesive approach to conserving native orchids. NAOCC and its growing network of collaborators share a common mission: to ensure the survival of native orchids in the U.S. and Canada. Through diverse approaches, including research, online tools, public outreach, and collective knowledge, they are making impressive strides toward achieving this goal.

White Fringeless Orchid: A Holistic Approach to Plant Conservation

The white fringeless orchid (Platanthera integrilabia) makes its home in acidic seeps and boggy areas near the heads of streams in open to partially shaded settings across Alabama Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and historically, in the Carolinas. Like many rare orchids, the white fringeless orchid has limited occurrences across its native range—most of which occur on public lands—and it faces myriad threats to its survival in the wild, including illegal poaching and destruction from feral hog activity. Today, this species is ranked as G2 – Imperiled by NatureServe and is listed as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFW). For the past decade, the Atlanta Botanical Garden Conservation and Research Department has been supporting the conservation and recovery of the white fringeless orchid through a multi-faceted, holistic approach that encompasses ex situ collections, field work, fungal research, reintroductions, and conservation partnerships—providing a model for a collaborative, comprehensive approach rare plant conservation.

The Conservation Seed Bank at the Atlanta Botanical Garden’s (ABG) is the foundation of its white fringeless orchid ex situ collections and holds more than 100 maternal lines, each contributing to a collection of well over 10,000 seeds. These seeds were collected from various locations, including Talladega National Forest in Alabama, Cherokee National Forest in Tennessee, Desoto State Park in Alabama, and two privately owned populations in the Piedmont region of Georgia. Seed banking orthodox seeds like that of white fringeless orchid involves careful curation and several key steps, including removing seeds from their capsules followed by desiccation for a week at 15% relative humidity before storage at a frigid -20°C to maximize their long-term viability. With this robust collection at its core, ABG has been able to further expand its conservation activities and research in support of this rare orchid species.

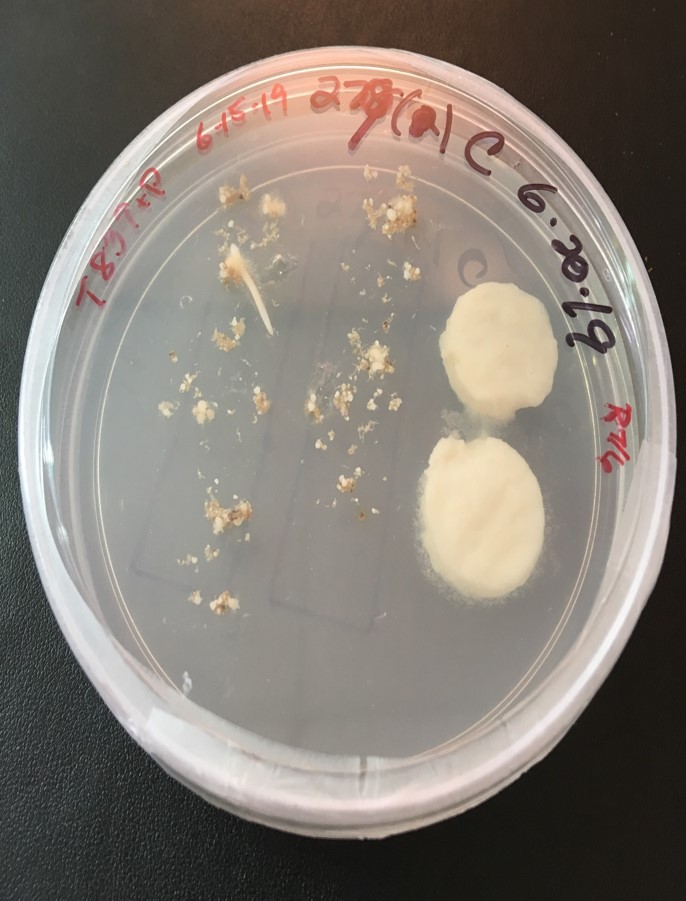

ABG’s current work with the white fringeless orchid focuses on the experimental reintroduction of extirpated populations using asymbiotic and symbiotically cultivated material and increasing ex situ collections. Beginning in 2017, the ABG team began collecting roots of white fringeless orchids to conduct research on orchid mycorrhizal fungi, which can be utilized to improve seed germination methods—often reducing the germination and growth time in half compared to asymbiotically cultivated specimens—and enhance survival rates of plants reintroduced to their natural habitats. In 2021, ABG identified a diverse range of fungi, including Calonectria, Ilyonectria, Agaricales, Pestalotiopsis, Sordariales, Hypoxylon fuscum, Hypoxylon fendleri, and Xylariaceae, and in 2022, the team collected additional roots from the Talladega National Forest in Alabama and the Cherokee National Forest in Tennessee.

Once roots were brought to the lab, staff meticulously cultured mycorrhizal fungi through a well-defined process, including soil debriding, surface sterilization before placement on Fungal Isolation Media, peloton extraction, culturing, and crucial genetic identification. Further attempts to identify and isolate known orchid mycorrhizae have been made this year with early success. This research on mycorrhizal fungi has proven essential to reintroduction efforts, not only in expediting the germination process and increasing plant survival rates in the wild, but also in helping to identify fungi strains found in specific habitats. Isolating habitat-specific orchid mycorrhizal fungi can augment and better support reintroduced plants in their natural habitats and has the potential to propagate other orchid species in the same habitat. As this research continues in the lab, efforts are also underway in the field to preserve the white fringeless orchid.

Collaboration and cooperative management are central to ABG’s conservation efforts. This is particularly helpful in managing a species like the white fringeless orchid which has populations spread across multiple states. In Alabama, ABG is working with partners to assess wild populations through the Southeastern Plant Conservation Alliance (SE PCA), with funding from the USFWS. Leveraging SE PCA partnerships enhances effective stewardship of resources and funding and maximizes conservation success for the species. Recent funding will contribute to expanding the footprint and impact of work with additional collaborators, incorporating new project sites in Alabama, Kentucky, and hopefully Mississippi.

Alabama populations, some recently discovered through predictive modeling conducted by the Natural Heritage Program at Auburn University and by Alabama Power, have been the highest priority to date for the SE PCA. Since 2020, site assessments and monitoring have been conducted by multiple partners, including Atlanta Botanical Garden’s Southeastern Center for Conservation, Auburn University’s Davis Arboretum, the Alabama Natural Heritage Program, USFWS, the USDA Forest Service, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and Alabama Power. These site assessments have informed management recommendations and planning with landowners, including Talladega National Forest and Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge, as well as state lands and powerline right-of-way sites. The accessioning of maternally-tracked material into ex situseed and leaf samples into ABG’s Conservation Seedbank and DNA Biorepository adds further value to the project and will be a source of material for genetic research and potential future reintroduction work.

Additionally, ABG has led the management and restoration of Piedmont bogs and seeps on public and private land in Georgia and has seen populations rebound after decades without flowering, including one thought to be extirpated on the Chattahoochee National Forest. The Kentucky Natural Heritage Program, within the Office of Kentucky Nature Preserves, is actively managing habitat containing this species. The Kentucky Natural Heritage Program and North Carolina Plant Conservation Program have partnered with ABG to reintroduce material propagated ex situ to sites of extirpated populations. If successful, these reintroductions will inform management guidelines for action that can be shared through the Piedmont Prairie Partnership and Southern Appalachian Bog Learning Network. These partnerships and collaborative efforts facilitate the sharing of knowledge and expertise, help address immediate conservation concerns for the white fringeless orchid, and guide future conservation actions for the ABG team.

Future work for conserving the white fringeless orchid includes plans to collect new seed this fall from six populations on Tennessee Valley Authority and Alabama Power powerline right-of-ways, Weyerhaeuser Company land, and other privately owned lands in Alabama that have never been accessioned into a seed bank. The continued growth of ABG’s ex situ collections (seed, leaf DNA, and root materials) will be utilized in ongoing research that informs additional propagation efforts and supports experimental augmentation and reintroduction—helping to bridge gaps between in situ and ex situ approaches to conservation and research that create success for species recovery and habitat restoration. This is facilitated through region-wide discussions through networks including the SE PCA that help to share knowledge about applied conservation and habitat management.

Through its work with the white fringeless orchid, the Atlanta Botanical Garden serves as a model for successful rare plant conservation whether in the lab, in the field, or in partnership with stakeholders—establishing a holistic and collaborative approach to conservation. The positive impacts of this work will be far-reaching for the survival of the white fringeless orchid and many other rare and endangered species under Atlanta Botanical Garden’s management and care.

Atlanta Botanical Garden wishes to recognize and thank their financial supporters, grant funders, and collaborators who have supported and contributed to this work:

- NFWF (National Fish & Wildlife Foundation)

- USDA-FS (United States Department of Agriculture – Forest Service)

- USFWS (United States Fish and Wildlife Service)

- NC-PCP (North Carolina Plant Conservation Program)

- OKNP (Office of Kentucky Nature Preserves)

- Patrick Thompson, Arboretum Specialist | Auburn University, Donald E. Davis Arboretum

- Katelyn Lawson, GIS Specialist | Auburn University, Alabama Natural Heritage Program

- Al Schotz, Botanist/Community Ecologist | Auburn University, Alabama Natural Heritage Program

- Ryan Shurette, Forest Biologist | USDA-FS, National Forests in Alabama

- Jonathan Stober, Wildlife Biologist | USDA-FS, Talladega National Forest

- Allison Cochran, Wildlife Biologist | USDA-FS, Bankhead National Forest

- Steven Trull, Refuge Manager | USFWS, Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge

- Geoff Call, Supervisory Biologist | USFWS

- Kerri Dikun, Fish and Wildlife Biologist | USFWS

- Brittney Hughes, Park Naturalist | Alabama DCNR, DeSoto State Park

- Dylan Shaw, Biologist | Alabama Power Company

- Dan Perry, MSAL/MSLA EMS Manager | Weyerhaeuser

- Mark Pistrang, Botanist | Cherokee National Forest, now USDA Forest Service Southern Region

- Jimmy Rickard, Forest Ecologist | USDA-FS, Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest

- David Vinson, Wildlife Biologist | USDA-FS, Chattahoochee National Forest

- Lesley Starke | formerly with the NC Plant Conservation Program

- Tara Littlefield Barry | Office of Kentucky Nature Preserves

________________________________

Special thanks to the Atlanta Botanical Garden Conservation & Research Department for their contributions to this article: Laurie Blackmore, Conservation & Research Manager; Dr. Emily Coffey, Vice President, Conservation & Research; Jason Ligon, Micropropagation & Seed Bank Coordinator; Dr. William Grant Morton, Conservation Seed Bank Curator; Carrie Radcliffe, Conservation Partnerships Manager; and Ian Sabo, Senior Field Biologist

An Orchid Oasis in the Heart of San Diego

Nestled between the baboons and meerkats of Africa Rocks and the gentle giants of the Elephant Odyssey, visitors of the San Diego Zoo find a haven for a different type of wildlife in the Orchid Greenhouse. Established nearly 50 years ago to celebrate orchids and their beauty, the Orchid Greenhouse has since taken an active role in global orchid conservation. With over 900 species of orchids, the Zoo’s collection is the seventh largest in North America by taxonomic diversity and the fifteenth largest in the whole world—an impressive feat!

The Zoo’s horticulture team shows off the orchids every month at Plant Day events, inviting guests to see the world-class collection and connect with threatened plants. Every plant has a story to tell! Some of the orchids in the greenhouse came to the Zoo in an intriguing kind of rescue. Poaching is a major threat to orchids in their native habitats, where they are removed from their habitat for a variety of reasons, including ornamental use.

Orchids are protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, meaning international transportation without a permit is completely illegal—but this doesn’t always stop poachers. Fortunately, as a designated Plant Rescue Center, the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) is able to provide a safe environment for plants confiscated in the illegal orchid trade.

When plants are confiscated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the country of origin is contacted to determine if they should be sent back. If the country of origin declines, the Zoo becomes caretaker for the confiscated orchids, either displaying them in the greenhouse or sending them to other Plant Rescue Centers for safekeeping. SDZWA orchid specialists propagate and grow subsequent generations of the poached orchids, which can be given to other botanical gardens for ex situ display and conservation—or, if appropriate, sold in plant sales on site. This process provides an opportunity to share a story that engages visitors with plant conservation and the plight of threatened plants. Sometimes, the plant material in the Zoo’s care may come from the last known population of a species! In the safety of the Zoo’s ex situ collection, surrounded by brilliant conservationists, material can be preserved and cared for to ensure ex situ survival, contributing towards conservation in the wild.

Since 2015, the SDZWA horticulture team has been working on in situ conservation in orchid biodiversity hotspots. One of these is the western Pacific island country of Palau, where 80 species of native orchids can be found. Last year, SDZWA orchid experts worked with local partners to collect seed and pollen from orchids in Palau. This project, a collaborative effort with the U.S. Forest Service and the North American Orchid Conservation Center, focuses on building up local capacity for orchid conservation in Palau through micropropagation training, providing nursery supplies, and building facilities at community colleges. SDZWA hopes to become involved with IUCN conservation assessments in the region in the future to help drive conservation efforts and interest. Another region of focus for in situ work is the southwestern U.S. – a Conservation Hub, or priority region, for SDZWA. In the Southwest, SDZWA collects pollen, seed, and other biological material from native orchids like Epipactis gigantea.

Orchids occur on every continent except Antarctica, and the SDZWA collection represents the family’s global diversity well. Heinfried Block, an orchid expert and Senior Plant Propagator at the Zoo, masterfully tackles the challenge of caring for such a vast array of orchids and enjoys taking on the more difficult-to-grow species. Propagation of orchids ex situ is a complex task, with in vitro growth demanding much expertise, knowledge, and specialized laboratory space. The SDZWA horticulture team has been remarkably successful at growing species from far and wide in the lab, covering many genera of orchids. One particularly challenging species to grow in the lab is Phragmipedium kovachii, a critically endangered Peruvian species subjected to rampant poaching in its wild populations. After receiving donated specimens of P. kovachii, SDZWA was able to successfully grow this plant from seed in the lab—an important accomplishment in the species’ conservation.

Back at home, the Zoo’s horticulture team engages the public with yet another popular event: Plant Days. On Plant Days, horticulture staff give Botanical Bus Tours of the Zoo’s flora and give talks by their Carnivorous Plant Greenhouse. Plant sales are held outside the Orchid Greenhouse to attract the attention of visitors.

These events allow the Zoo to share about plant conservation and the Zoo’s global and local efforts. According to Adam Graves, Director of Horticulture, “When we talk about the conservation status of a lot of these plants, it’s really an eye opener for a lot of people…it’s a gateway conversation to get them more familiar with the need for plant conservation.” Plant Days help draw visitors in to learn about threatened plants. While many guests are surprised to learn about the Zoo’s vast horticultural collections, their orchid collection provides yet another surprise in the form of U.S. native orchids.

SDZWA’s efforts to engage the public with plant conservation help visitors understand how each of them can make a positive impact. The horticulture team’s expertise with exceptional species, such as orchids, cycads, and oaks, makes this conservation niche an important focus. Future directions for the horticulture team and orchid experts include expanding further into long-term cryopreservation, ecosystem-level stories involving all species in a system, and more public-focused education programs. This broad-ranging work with threatened orchids provides a stellar example of SDZWA’s global leadership in conservation.

-

Spathoglottis micronesica, one of 80 orchid species occurring in Palau. 28 of those orchid species are endemic to the islands, underlining the role of in situ as well as ex situ conservation. Photo courtesy of SDZWA. -

Phragmipedium kovachii is difficult to grow in the lab, but SDZWA staff have found success! Pictured here growing in the SDZWA orchid greenhouse from seed. Photo courtesy of SDZWA. -

SDZWA Orchid Greenhouse. Photo courtesy of SDZWA.

Dr. Peter Zale

Our October Conservation Champion, Dr. Peter Zale of Longwood Gardens, channels his passion for native orchids and scientific expertise to advance orchid conservation science through innovative lab-based seed germination techniques, establishing living collections, peer-reviewed research, public education, and more. While some native orchid species may prove elusive to work with at times, Peter proves that patience and dedication can result in long-lasting, meaningful impacts that ensure these delightful plants survive for generations to come.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

During my freshman year in high school, I was assigned a leaf collection project to learn more about identifying local woody plants, how to use a dichotomous key, and preparation of herbarium specimens. The teacher had a list of rare, unusual, and difficult-to-find species that were extra credit if included in the final project. As a kid interested in collecting all types of things, this had tremendous appeal to me, and I became intensely focused on finding these rarities. My family was hugely supportive of the project and drove me near and far to collect specimens. The project was a huge success—I ended up with something like 300 out of 100 points—but I didn’t want it to end!

Afterwards, I continued to search for all the rare trees I could locate during the project, visiting every local nursery and garden possible, and started filling my mother’s yard with unusual plants. During a visit to the Holden Arboretum not long after the project ended, I picked up a flyer with a line-drawing of the large yellow lady’s slipper (Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens). It was nothing short of a revelation! I remember thinking “orchids grow in Ohio?!”—and from that point I was hooked. I knew I wanted to work with plants, and particularly native orchids, for life.

What was your career path to Longwood Gardens?

Working for a public garden was something that didn’t come onto my radar until grad school. I attended The Ohio State University, where I started in landscape design but quickly changed course once I started learning about the science of horticulture—seed science, plant propagation, and plant identification. Ultimately, I obtained a bachelor’s degree in horticulture science. I then had the unique opportunity to help develop and then manage a certified organic retail and wholesale nursery that focused on native plants. Through this experience, I was able to collect seeds and learn propagation protocols for a wide variety of native plants—but it left me wanting more.

I returned to graduate school, where I studied the quantitative genetic characteristics of a breeding population of Magnolia virginiana and made seed collections throughout the species’ range, with the idea of continuing genetic work on this project for my Ph.D. However, an opportunity to pursue my Ph.D through the Ornamental Plant Germplasm Center (OPGC) led me to focus on germplasm collection development, through extensive botanical field work, genetic characterization, and interspecific hybridization of the genus Phlox. During my time at OPGC, several public garden curators visited and strongly encouraged me to pursue a similar role in a public garden. The idea had never occurred to me, but ultimately it was the best professional advice I ever received. The week before I defended my dissertation, the position at Longwood opened. I started as Curator and Plant Breeder in 2015 and immediately initiated our native orchid conservation program.

What native orchid conservation initiatives are you most excited about?

I am most excited about some of the laboratory-based seed germination techniques that allow us to not only expand the role of horticulture and collections development of native orchids in a public garden setting, but also provide unique avenues for original research. This is particularly exciting because there is an often-perpetuated myth that native orchids are difficult or impossible to grow—and it is simply not true. Our work illustrates this through the establishment of living collections in the gardens and peer-reviewed research. The native orchid conservation team at Longwood has embraced a similar approach; it has been exciting to watch them expand, develop, and experiment with seed germination techniques in ways that have and will continue to help us contribute to the science of orchid conservation.

What successes or challenges have you encountered in your work?

I am particularly proud that we have been able to “crack the code” for a handful of native orchid species that have been considered difficult or impossible to germinate. For example, we were able to germinate and grow seedlings of Platanthera peramoena, a state-listed species in PA that is of conservation concern throughout much of its range, which has been considered extremely difficult to germinate using mature seeds. We implemented a series of studies to determine the potential for using embryo culture work to successfully germinate this species.

Embryo culture—a well-known method for circumventing seed dormancy in mature seeds—has been tremendously successful in orchid conservation work by other institutions but requires a specific knowledge of seed maturation time and timing of seed harvest. Through meticulous hand pollination and serial harvest of seeds, we determined how to effectively and repeatably propagate this species when seeds are harvested at 26 days after pollination. We have even been able to extrapolate the technique to closely related species, with the hope that it can eventually be applied to endangered species such as P. leucophaea and P. praeclara.

Educating the public about native orchids continues to be an important area of focus for us. In early 2022, Longwood Gardens opened its new orchid house to the public. My team had the opportunity to set a display table highlighting our conservation work with native orchids. 8,000 people visited the conservatory that weekend—and it felt like we talked to just about all of them!

We were shocked to discover that probably 9 out of 10 people have no idea that orchids grow naturally in PA, let alone that at least 60 taxa of orchids have been found historically throughout the state. After learning about them, one visitor remarked, “Wow, so many orchids in Pennsylvania…who brings them all in in the winter?” Although this statement initially made us chuckle, it gets at the larger issue that most of the public only associate orchids with the tropics or houseplants, and generally have no idea that orchids can literally be found in their backyard. From that experience, it became clear to me the importance of increasing public awareness about native orchids in tandem with their need for conservation.

What has surprised you about working with and learning more about rare orchids?

The most surprising thing about native orchids is that rarity in the wild does not mean an orchid will be difficult to propagate or grow—and an orchid that is more common is not necessarily easy in the same regard. For example, Cypripedium kentuckiense is one of the rarest native orchids in the U.S., but we find it to be among the easiest to propagate and grow of all the native orchids we have worked with. Conversely, the showy orchid (Galearis spectabilis) is among the most common orchids in our region and occurs naturally on Longwood Gardens property, but it has proven to be one of the most difficult to propagate and grow! This pattern has been repeated throughout our experience with a variety of native orchids and never ceases to surprise us.

What advice would you give to those who wish to learn more about how they can help save imperiled plant species?

I would first suggest that anyone interested in plant conservation find and join a local plant conservation alliance. These organizations are spread throughout the country and are the hub that unifies scientists, horticulturists, botanists, ecologists, and anyone interested in any aspect of plant conservation. Pennsylvania has a progressive and engaged plant conservation alliance in which we are very active. It has been a tremendous boon for our orchid work and as we continue to expand our ex situ conservation and restoration efforts to other rare plants from the state.

Working with native orchids has taught me the importance of patience, dedication, and humility. Eight years into our orchid conservation program, there are days when it seems like we’re making progress, and other days when I feel like we just started! Those wishing to work in orchid conservation should understand that quick victories may be elusive. Real results often take time, but those results can be incredibly long-lasting. Our work with lady’s slipper orchids exemplifies this—with estimated generation times of 100 to 400 years, plants we are propagating, conservation collections we are building, and populations we are restoring have the potential to tell our conservation story for centuries to come.

National Collection Spotlight: Case’s ladies tresses

Case’s ladies tresses (Spiranthes casei) is a native North American orchid imperiled throughout much of its range. This species can be found in the northeastern U.S. and eastern Canada, from Minnesota to Nova Scotia. A terrestrial orchid, Case’s ladies tresses grows in open woodlands and meadows. Its small white flowers are held on a twisting inflorescence characteristic of Spiranthes species (the genus’s Latin name means spiral flower).

Spiranthes casei is secured in the CPC National Collection at Longwood Gardens. In addition to collecting and storing seed from wild populations, Longwood has conducted propagation research and tissue culture for the species. Longwood is working to restore populations of Spiranthes casei in Pennsylvania, where the species is endangered and faces heightened threats.

Learn more about conservation actions taken for Case’s ladies tresses on its National Collection Plant Profile, and help support critical conservation work for this species with a Plant Sponsorship.

As Seen on CPC’s Rare Plant Academy: Orchid Micropropagation

Micropropagation is an effective conservation tool for producing tissue clones or for germinating spores or seed in vitro. Orchids are known to be quite difficult to propagate as they typically require fungal symbionts during their germination. In this video created for the Rare Plant Academy, Jason Ligon and Tito Tomei explain how to propagate orchids in the lab using sterile micropropagation techniques. They show each step and emphasize how important sterility is for the process. Watch this video and check out the Rare Plant Academy Video Library to watch many more videos and presentations focused on orchid conservation!

This video was made possible through an Institute for Museum and Library Services grant.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Ways to Help CPC

Conservation Advocacy Initiatives

Advocacy is an important tool at our disposal to use in saving rare and endangered plants. As conservationists, botanists, plant enthusiasts, and humans on Earth, we must all use our voices to advocate for plants. Just as we need plants, they also need us to ensure their continued survival and conservation 🌱

What can you do to be an advocate for rare plants? Stay informed and reach out to your representatives! The Center for Plant Conservation tracks federal legislation with direct impact on the safeguarding of rare and endangered plants, plant conservation research, and restoration. Visit our Advocacy page (saveplants.org/advocacy) to learn more about current legislation in the #PlantConservation world 📰🌳

Photo: Three-birds orchid (Triphora trianthophora), which is potentially threatened in Ohio and uncommon throughout its range. Photo by Doug Berube, courtesy of The Dawes Arboretum.

Donate to Save Endangered Plants

Without plants, life as we know it would not be possible. Yet two in five of the world’s plants are at risk of extinction. More than ever before, rare plants need our help!

That is why all of us at the Center for Plant Conservation (CPC) are deeply grateful to have you as part of our conservation community. Your generous and unyielding support allows CPC and our network of world-class botanical institutions to make great strides in our shared mission to Save Plants from extinction.

Your gift ensures CPC’s meaningful conservation work will continue. Together, we save more plants than would ever be possible alone—ensuring that both plants and people thrive for generations to come. We are very thankful to for all that you do to help us Save Plants!

Donate to Save Plants Today!

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today