Save Plants

Center for Plant Conservation

The significance of rare plants on islands extends far beyond their aesthetic or botanical value. These unique species are vital in the intricate web of life that makes up island ecosystems. Often evolving in isolation, island floras possess unique adaptations that have come to define the character of their respective habitats. From soil fertility to providing food and shelter for wildlife, these plants serve as cornerstones that maintain a balanced ecological structure.

Islands are often referred to as “hotspots” of biodiversity precisely because their isolation allows for the evolution of unique species not found elsewhere. We call these species “endemic,” and they are irreplaceable. The loss of any rare or endemic plant species is a blow not just to the island but to global biodiversity. Additionally, these plants can be repositories of genetic material that could be crucial for the adaptation and survival of related species elsewhere, especially in the face of climate change.

Island plants often show specialized relationships with local fauna, themselves often endemic or rare. These can include exclusive pollination “agreements” with certain insects or birds, or specialized seed dispersal mechanisms. When a rare plant species disappears, it can create a domino effect that impacts various other organisms that rely on it for survival, ultimately destabilizing the ecosystem.

There’s also the human element to consider. Many island communities have a deep cultural connection to their native flora, which often includes rare plants. These plants may have traditional uses, from medicine to construction materials, and their loss can erase a part of the island’s cultural heritage.

In this issue, you’ll travel to the tropical islands of Puerto Rico with Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden to learn about their conservation work with rare and listed ferns, and to Hawaii with the the Laukahi Network, who endeavor to implement the Hawaii Strategy for Plant Conservation. We also celebrate our November Conservation Champion, Dr. Heather Schneider, from Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, and her work in the California Channel Islands.

The conservation of rare plants on islands isn’t just a niche interest—it’s a necessity that holds implications for biodiversity, ecosystem stability, and even cultural preservation. As we navigate the ongoing environmental challenges of our time, prioritizing the conservation of these unique island plants becomes not just a matter of scientific interest but a global imperative.

Conserving Puerto Rico’s Rarest Ferns

What do ferns and Puerto Rico have in common? They are both frequently left out of U.S. plant conservation efforts! Ferns are frequently overlooked because they are not very showy and do not produce flowers or seeds. While no one can accuse Puerto Rico—with its gorgeous beaches and mountains—of not being showy, the lack of statehood and physical distance from the mainland often make it an afterthought for U.S. conservation efforts and funding.

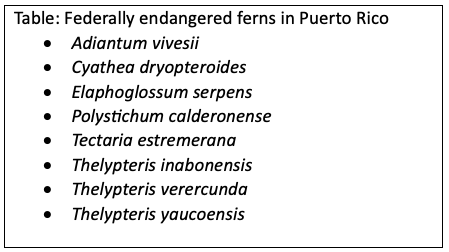

As a long-time (23 years!) biologist at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Miami, it has been a privilege and a joy to work with a tiny percentage of Puerto Rico’s amazing fern flora. For this most fun facet of my career, I owe thanks to a chance meeting in 2012 between Fairchild’s then-Conservation Ecologist Dr. Joyce Maschinski and USFWS Recovery Biologist Omar Monsegur. When Joyce and Omar met at an IUCN cactus Red Listing workshop in 2012, they began to hatch plans for what turned out to be a long-term and fruitful collaboration to safeguard several of the island’s rarest plants. In 2014, Joyce, Omar, other collaborators and I began work with four federally listed species found in the Sierra Bermeja region, as well as eight federally endangered fern species (see Table) in the western portion of Puerto Rico’s Cordillera Central. With our many partners, including the CPC, I am proud to carry on this work today.

Working with Puerto Rico’s eight listed fern species has not been without challenges! Most of the species are difficult to identify, having key characters that overlap those of similar species. In fact, the majority of these ferns pose challenges to our concept of a species: some may be sterile hybrids (Adiantum vivesii, Tectaria estremerana), and others differ only slightly from closely related, much more common species (Thelypteris verecunda, Thelypteris yaucoensis). Additionally, many of these ferns had or have occurrences that were destroyed, poorly documented location information, and/or remote, hard-to-reach locations (Thelypteris inabonensis, which we have not yet managed to survey).

We have made inroads with most of the eight fern species—albeit some more than others. Fairchild has a small but healthy ex situ collection of Cyathea dryopteroides from just one of several known occurrences. Puerto Rico Department of Natural & Environmental Resources (DNER) biologist Jose Sustache has located several additional and previously unknown populations of C. dryopteroides. Excitingly, Sustache also rediscovered not one but two occurrences of Elaphoglossum serpens, a unique and pretty fern that was thought to potentially be extinct, having not been seen in several decades. For our part here at Fairchild, by far the most progress has been made with Polystichum calderonense, the Guilarte Holly Fern.

Polystichum calderonense is a medium-sized terrestrial fern endemic to the municipalities of Adjuntas and Peñuelas in Puerto Rico’s karst belt. Although P. calderonense has been reported in a few locations within Guilarte State Forest and on nearby private property, the only plants that have been observed in the past decade are at the type locality in the Guilarte Forest.

Over the span of nine years, we have helped local biologists to document the decline of this already tiny population, from 15 plants in 2014 to 7 in 2023. The reasons for the decline were primarily natural phenomena, though one could argue that these were exacerbated by human-caused climate change. A fire—likely caused by lightning—killed some of the ferns in 2014, and damage from Hurricane Maria is suspected to have caused almost half of the population to perish in 2017. But humans may have directly caused negative impacts as well, as the site is popular for hiking and as a selfie spot.

Fortunately, there has been quite a bit of good news to offset the challenges. Propagation of P. calderonensehas been blessedly easy, with not one, but two methods available. Mature plants produce copious spores which germinate well (approximately 75% success in testing in Fairchild’s seed lab). It takes approximately 2 years from the time of spore-sowing to generate plants that are appropriately sized for reintroduction (i.e., quart-sized pots). Mature plants also produce proliferous buds at the tips of their fronds. These are fairly easy to propagate (we start them in sphagnum moss) and are a quicker way to grow a plant that is of planting size, since it bypasses the gametophyte stage.

In 2021, after several years of planning, we began a series of small pilot plantings throughout the species’ natural range. We introduced 21 plants to 4 locations but provided no aftercare, due to access difficulties. We did, however, take an experimental approach, selecting a variety of different soil types and logging temperature and humidity data at each outplanting location. Happily, one year later, we found 15 plants had survived—not bad for no aftercare!

In 2023, we tried another outplanting method, but the jury is still out as to whether it worked. We added nursery-collected spores to hydrated peat balls and pushed them into cracks in limestone. This method is very easy to do, does not require care and transport of live plants, and does not require us to locate a space where we can dig deep enough to plant a fern’s roots. Ask us in 2026 if we had any success!

Today, we have hundreds of P. calderonense in cultivation at Fairchild that can be used for reintroductions in Puerto Rico. Through the pilot plantings, as well as through ex situ cultivation, we have learned quite a bit about the species’ microhabitat needs. The ferns perform best in relatively dry peat/humus substrate, and they prefer high humidity and partial shade. In the next few years—together with our Puerto Rican partners—we hope to reintroduce dozens of plants back to the Guilarte Forest and nearby protected areas.

Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden and the USFWS have been just two of several enthusiastic partners working toward recovery of federally listed ferns and species in the Sierra Bermeja region. Other agencies critical to the efforts include the DNER, University of Puerto Rico at Mayaguez, University of Florida, Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden’s Lindner Center for Research on Endangered Wildlife (CREW), and Para La Naturaleza. We thank our friends at these agencies as well as several private citizens for their collaboration.

-

View from Pico Rodadero, where we searched for but did not relocate one of the listed fern populations. Photo credit: Jennifer Possley. -

Polystichum propagated by Fairchild tropical Botanic Garden. Photo courtesy of Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden. -

On top of the world (Monte Guilarte) in 2022 with Octavio, Coralys, Lindsey and Jennifer. Photo courtesy of Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden.

Aloha ʻĀina: Conserving Hawai'i's Native Flora

Plant conservation is essential in Hawai‘i to preserve its unique flora, which has a critical role in maintaining native ecosystem health and sustaining life. The Hawaiian flora has one of the highest rates of endemism in the world (90% for angiosperms, 74% for ferns and lycophytes). Approximately 10% of the flora is extinct, and over 30% (of 1,390 species) are federally listed as threatened or endangered. It is estimated that 72% of the vascular flora is threatened with extinction, making it one of the world’s most threatened. Increased and novel conservation measures are urgently needed to save what remains.

The conservation of Hawai‘i’s flora is challenging. Reasons for the decline of native species are numerous, often centered around the introduction of ~6,000 non-native species, including plants (e.g., Miconia calvescens), invertebrates (e.g., slugs and snails), rodents (e.g., rats) and ungulates (e.g., wild boars). New introductions of invasive species, such as the Coconut Rhinoceros Beetle which threatens Pritchardia palms, continue to assault native ecosystems. Populations of many plants (e.g., Schiedea spp.) are small and fragmented, facing threats such as dwindling genetic variation and reduced outcrossing as pollinator populations decline or disappear. Looming threats like climate change and wildfire pose increasing risks. Climate models predict that 5% of the flora of Hawai’i will have no remaining habitat by 2100.

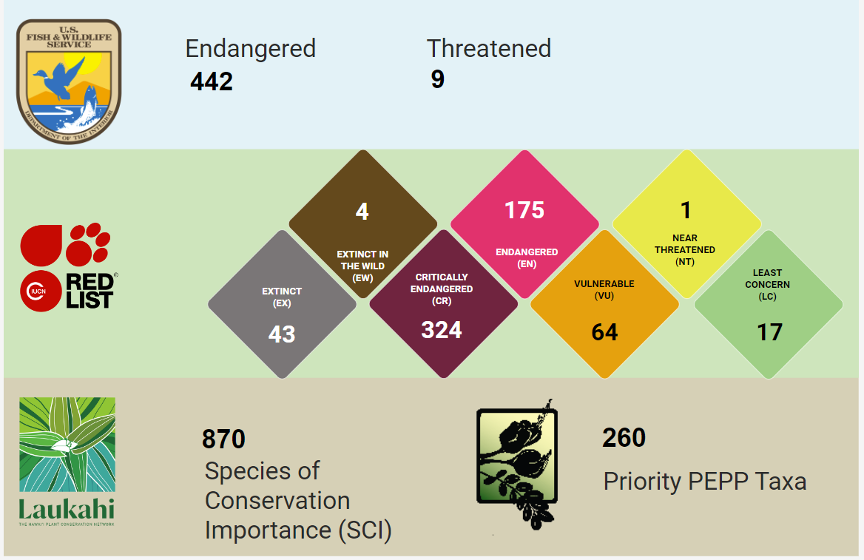

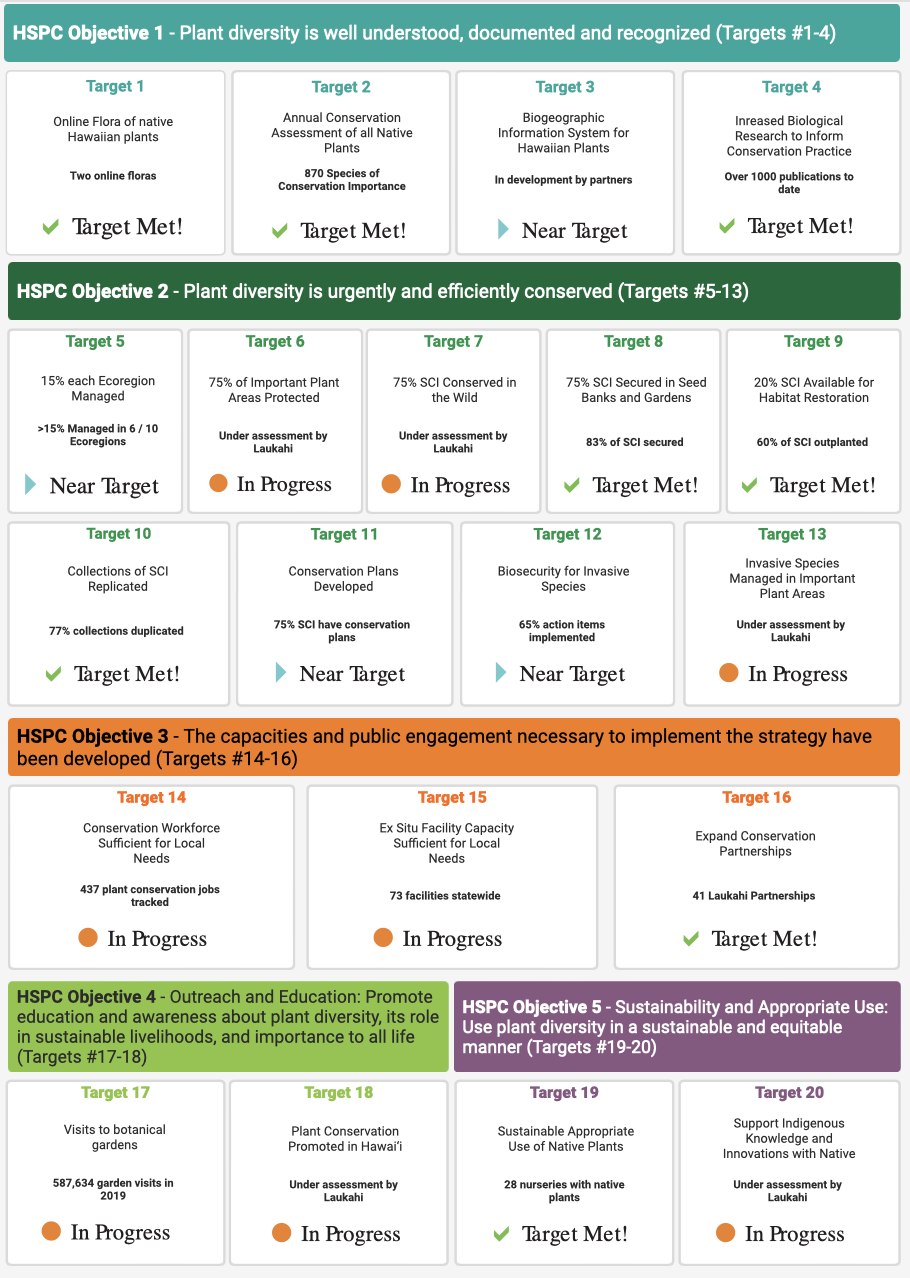

The rapid decline of native plants made clear that an overarching, coordinated, conservation strategy was needed. Laukahi, The Hawai‘i Plant Conservation Network, formed in 2016 as a non-profit organization that coordinates a voluntary alliance of agencies, non-profits, community groups, organizations, and individuals dedicated to protecting native Hawaiian plants. Laukahi emerged after a statewide capacity assessment, resulting in the Hawai‘i Strategy for Plant Conservation (Strategy). The Strategy defines 20 targets that align with 5 major global conservation goals: understanding plant diversity, conserving plant diversity, building capacity to implement strategy, outreach and education, and sustainability. Laukahi tracks 870 Species of Conservation Importance (SCI), including rare and other ecologically and culturally important species.

Driven by a full-time coordinator and contributions from 42 partners, Laukahi has made significant progress on the Strategy since 2016. We first focused on the urgent need to coordinate and expand ex situ conservation—securing SCI in protected collections before they were gone from the wild. The coordinated efforts of Laukahi and the network accelerated the growth of ex situ collections significantly. Together, we developed best practices for working with rare plants and published the data and our progress as a dashboard on our website. From 2012 to 2020, SCI secured in ex situ collections grew from 73% to 83%—exceeding the 75% global target. We continually update species collection needs for each island, ensuring the availability of rare and ecologically important plants for future ecosystem restoration activities.

In the last year, we launched our first in situ assessment of native plants. This is necessary to understand plant distributions and habitats in the wild and to determine if protection and management are adequate for their long-term survival. Thanks to our network partners, we have gathered the data required for the assessment. Once our analysis is completed, Laukahi will communicate the results to conservation programs state-wide, to inform and guide actions prescribed in the Strategy.

With each assessment and gap analysis we complete, we adjust our needs. The assessments document the status conservation activities and identify steps that should be taken by the network to meet goals. This informs our future activities, such as seeking a missing dataset on control of invasive rodents in our in situ assessment or including valuable sources of plant materials like fern spores in our ex situ assessment. Recently, we completed 112 IUCN Red List assessments of Hawaiʻi’s 328 native trees, identifying new SCI to incorporate into the Strategy’s targets. We remain flexible to respond to evolving needs, such as the recent wildfire disasters. As the broader community responds, Laukahi’s master inventory of all native plant materials stored in seed banks and gardens will enable us to inform initiatives to restore native forests in areas currently dominated by fire-prone invasive grasses.

To support building public engagement, Laukahi started a new project focused on biocultural connections called Nā Inoa Meaulu, which translates to the Hawaiian Plant Names. Hawaiian names of plants are applied inconsistently today because authoritative summaries of names are scarce or incomplete. This project will combine references on Hawaiian names of native plants into a single resource to be shared with botanical gardens to support their many outreach activities, and it will be made publicly available on our website for the use of other interested stakeholders, such as ‘ōlelo Hawaiʻi speakers and educators.

Our challenges are big, but our aloha ʻāina is much bigger! A simple translation of aloha ʻāina is a love of the land, but it extends as a much deeper concept and connection of land stewardship in Hawai‘i. The Network collaborated long before the formation of Laukahi formalized interactions. Partners say they “work for the plants,” focusing on serving the plants. The relationships in our network are strong, with reciprocation and collaboration forming natural aspects of our activities. With these efforts, people have demonstrated their aloha ʻāina. Though Hawaii has long been known as the world’s capital of endangered species, we want to be acknowledged one day as the world’s capital of biodiversity through our conservation efforts.

Rare and Endemic Plants on Islands: Stories of Rarity, Risks, Recovery, and Resilience

The first time I set foot on Catalina Island, one of the eight California Channel Islands, I was excited, stunned, and concerned. I was excited to meet several plant and animal species that were only found on this island, the Catalina endemic species. Seeing a species with such a narrow distribution opened a veritable book of topics to learn about and explore. Where did they come from, and how did they get here? What unique adaptations evolved to make them so distinct from the original mainland species to justify creating a new species classification for them? The breadth of topics was broad and exhilarating, so much so that I even co-wrote a book about the Island’s wildlands and am ready to publish a second book on the natural history of many of its unique species.

At the same time, I was stunned to see so many non-native species, some of which had taken over vast areas of the Island, pushing out and outcompeting the native species. I encountered for the first time the Dyer’s greenwold (previously known as Canary Island or flax-leaved broom, Genista linifolia), a species introduced as an ornamental in the early 1900s to decorate the gardens of a hotel. In their original habitat (the Canary Islands), a suite of vertebrate and invertebrate herbivore species and fire keep this species tightly controlled, pushing it to evolve some strong adaptations to survive. For example, they produced seeds that could stay viable in the meager soil for decades. Their bright green foliage and beautiful yellow flowers made them attractive to the hotel owners in Catalina. But they escaped the confines of their pots and literally exploded in the canyons adjacent to the town of Avalon. Without their natural controls, they took over, expanding to cover around 60-70% of the hillsides around the town. In total, over 250 species of ferns, conifers (pines), monocots (like grasses), and dicots (such as flowering plants) have been introduced to the Island. Luckily, only a few of them are considered highly invasive, and the Island conservation area managers have addressed the worst of them over the years.

I was also concerned about the impact of so many years of heavy grazing of the hillsides, the degradation of the few freshwater springs and creeks, and the erosion from all the roads that crisscross the Island. I focused on prioritizing the issues and designing or expanding programs to improve the health of the native species. I had come to Catalina as the new Chief Officer for Conservation and Education of the Catalina Island Conservancy—I took this job seriously and with enthusiasm. For the next 6.5 years, I worked with an engaged community of residents, visitors, businesses, agencies, and scholars to protect what was irreplaceable and improve opportunities for the native species to recover and thrive from decades of impact.

It has been over 15 years since I left the Island to pursue other conservation priorities, but the work in Catalina continues, facing challenges that go well beyond the ecological realms, including social, historical, cultural, economic, political, ethical, and even, at times, spiritual concerns. Each of the eight California Channel Islands faces similar but unique mixes of issues. In fact, all the islands of the world face similar challenges, particularly regarding the islands’ rare and endemic species. Here are some of the significant hurdles they encounter.

Invasive Species: One of the most pressing issues is the introduction of invasive species, which often outcompete native plants for resources. For example, invasive grasses in Hawaii have drastically changed the landscape, making it difficult for endemic species to survive. Invasive species can quickly spread and monopolize sunlight, water, and soil nutrients, leaving native plants with little chance of survival.

Changing Climate: Climate change introduces a slew of challenges for island ecosystems. Rising temperatures can shift suitable habitats, and many endemic plants may find it difficult to adapt. Altered precipitation patterns can exacerbate this, either by inducing droughts or increasing rainfall to a point that the native flora cannot handle. For example, many of the Galápagos Islands’ unique plant species are suffering due to less predictable rainfall patterns.

Fire: Fire regimes are changing on many islands, often due to human activities or the introduction of invasive species that are more fire-prone. Endemic plants that have evolved without natural exposure to frequent fires may not have the mechanisms to cope with increased fire events. After a fire, invasive species are often the first to colonize the area, making it challenging for native plants to regain their territory.

Anthropogenic Issues: Beyond the direct threats of urbanization and land conversion for agriculture, other human-related challenges include pollution and the collection of rare plants for trade or gardening. The small populations of these rare and endemic species make them incredibly vulnerable to any form of habitat loss. In some islands, tourism is a double-edged sword. While it brings attention and potentially more conservation resources to these unique ecosystems, the foot traffic and accompanying development can also pose threats.

Conservation Strategies: Designing appropriate conservation strategies for these rare and endemic island plants is crucial. Invasive species management, including biological controls, can help native plants regain footing. Protected areas can offer a sanctuary from human-related issues—but they must be well-managed to prevent the incursion of invasive species and human disturbance. Some islands are turning to ex-situ conservation efforts, like seed banks and botanical gardens, as a form of insurance against extinction.

The interconnectedness of these challenges often amplifies their individual impacts, making it a complicated issue to tackle. However, solutions are not unattainable, especially if we approach them from a systems-thinking perspective, considering how each factor influences the others. To preserve the incredible biodiversity that islands offer, proactive and multi-faceted conservation strategies are essential.

Catalina Island and the other California Channel Islands are a microcosm of the challenges and conservation efforts concerning rare and endemic plants. The islands are home to dozens of plant and animal species that are not found anywhere else in the world. The protection, research, and conservation of these unique species is one of the main priorities for the organizations and agencies that manage these islands, and this management must include healthy, collaborative, participatory, and engaged community processes.

-

Cliff spurge (Euphorbia misera). Photo credit: Carlos L. de la Rosa. -

The flowers of the endemic Catalina manzanita (Arctostaphylos catalinae) resemble small upside-down amphoras. Only the smallest of insects are able to enter the flowers and reach the pollen and nectar. -

Santa Catalina Island Ironwood (Lyonothamnus floribundus ssp. floribundus). The leathery leaves are not immune to insect damage. Caterpillars of several species are known to feed on the leaves. Note the damage shown here. Photo credit: Carlos L. de la Rosa.

Heather Schneider

Our November Conservation Champion, Dr. Heather Schneider, brings her intrinsic love of nature, scientific curiosity, and adventurous spirit to her rare plant conservation work at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden where she protects, restores, and advocates for California’s rare plants. Heather’s work to conserve the rare and endangered plants of the Channel Islands highlights the unique challenges and opportunities faced by practitioners working to protect island species, and the progress that can be made through partnership and collaboration. As Heather states, “We can all be a force for rare plant conservation, whether our actions are big or small.”

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I’ve always loved being outside. I grew up in the Midwest camping with my family and playing in our backyard, chasing lightning bugs and catching toads. But I didn’t find my passion for plants specifically until I was in college. Like a lot of kids, I was an animal lover and I think that school biology classes are biased towards animals, so I’d never considered a career in botany. When I got to college, I had the opportunity to take classes at The Morton Arboretum, another CPC Conservation Partner, that counted toward my biology major. I took a course on ethnobotany that was taught by a rotation of scientists from Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History. I was blown away by the lives that these people led, the sense of adventure that their work entailed and the incredible science they were doing—all focused on plants. I took a taxonomy class focused on plants of the western Great Lakes and it opened my eyes and taught me the names of the plants I’d grown up with. After those two classes, plus an upper division ecology course on campus, I was hooked. I realized that studying plants could combine my love of nature and spending time outdoors with the scientific curiosity I was fostering as an undergraduate and I never looked back.

What was your career path to Santa Barbara Botanic Garden?

I went to a small liberal arts college outside of Chicago called Elmhurst University, where I majored in Biology. Although I didn’t have the same research opportunities that are available at large research institutions, I did have some unique opportunities like the classes at The Morton Arboretum and crafting a personalized internship with the Department of Conservation and Land Management in Katanning, Western Australia, where I spent 3 months working on a wide array of projects, including working in an herbarium and conducting rare plant surveys. That was when I realized that I could get paid to hike and go camping! I also had professors who got to know me and one in particular who suggested that I apply to graduate school. I had never considered graduate school—no one I knew had been and I didn’t know whether I had what it took. Thankfully, my mentor helped me hone in on my interests and find potential advisors to reach out to. From there, I earned a PhD at the University of California, Riverside studying the impacts of anthropogenic nitrogen deposition and invasive plants on California’s desert wildflowers.

After graduating, I worked for the US Geological Survey studying desert tortoises and their habitat before taking a postdoctoral fellowship at UC Santa Barbara. In Santa Barbara, I helped develop a first-of-its-kind research seed bank to study the evolution of wild plants (Project Baseline) and investigated the evolutionary ecology of two species in the genus Clarkia. When I saw the ad for the job at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, I was excited to have the opportunity to focus on applied conservation work. As the Senior Rare Plant Conservation Scientist at the Garden, I get to focus all of my energy on understanding, protecting, restoring and advocating for California’s rare plants. I work with a great group of folks at our Garden and external collaborators who are all doing what we can to prevent extinction. I’ve been at the Garden for seven and a half years and am excited to see how much our team and our impact have grown.

In your experience, what are some of the unique and/or pressing conservation needs impacting the rare and native plants of the Channel Islands?

The Channel Islands are such a unique system in which to work—they simultaneously harken back to California’s past as refuges for relictual species like the island ironwood (Lyonothamnus floribundus), while also showcasing the incredible evolutionary processes that happen under the geographic isolation of island systems. Islands harbor a large amount of the unique biodiversity across the globe, but they have also suffered from a disproportionate number of threats and extinctions. One of the many threats that islands face is that they are isolated land masses and plants can’t move very far to escape threats. For example, when we think about potential climate change related translocations on the California mainland, we often think about moving things northward or upslope to chase cooler, wetter conditions. That’s harder to do on islands.

In California’s Channel Islands archipelago, we could potentially move plants to the next island in the chain, but that poses its own potential problems with gene flow and eventually we’ll run out of islands. However, the isolation of islands also provides opportunities. For example, there have been successful eradications of introduced animals on the Channel Islands precisely because they are relatively closed systems. So, we can tackle some problems on islands, like invasive Argentine ants, that would be impossible to address on the mainland. It’s a mixture of challenges and opportunities, so we try to leverage any advantages to the extent possible.

What conservation initiatives are you most excited about in the Channel Islands?

One of the things that I’m most excited about is the growth and expansion of collaborative conservation work across the Channel Islands archipelago. Santa Barbara Botanic Garden is part of a consortium of nonprofit, private, and governmental partners who are working on various aspects of island conservation and management across all of the California’s islands—the Islands of the California’s Botanical Collaborative (ICBC). ICBC includes partners working across the islands off the coast of both Alta and Baja California. We share lessons learned, share data, and are working towards a standardized rare plant mapping protocol for the entire Channel Islands archipelago. We’ve successfully fundraised for some large, rare plant conservation and recovery projects and have adopted a somewhat programmatic approach to our work: setting priorities, seeking funding and executing actions in a stepwise fashion. It’s been really inspiring to see so many different types of partners collaborate to advance conservation and recovery goals. We accomplish so much when we work together.

What successes or challenges have you encountered in your work?

We’ve had a few big successes that I’m excited about. Recently, I led a large collaborative project on seven of the eight Channel Islands (all except San Clemente Island). Our partners included The Nature Conservancy, Channel Islands National Park, USGS, California Institute for Environmental Studies, Wildlands Conservation Science, USFWS, US Navy and CDFW. Over the four years of the project, we documented 540 rare plant observations, brought 108 new conservation seed collections into the Garden’s conservation seed bank, discovered 12 previously undocumented rare plant populations and produced more than 400,000 seeds in the Garden’s nursery for population creation and augmentation on the islands. It was a huge effort that made a big impact on our ability to understand, protect and restore the islands’ rare plants. Now one of those plants, Santa Cruz Island liveforever (Dudleya nesiotica) has been proposed for potential delisting from the federal endangered species act, in part due to the recent surveys and status update that our team conducted, along with robust conservation seed banking efforts led by the Garden.

The biggest challenge of working on islands is always logistics. We access most of the Channel Islands via boat, so if seas are rough or we have prolonged storm systems come through, then we can’t get to the islands to do our work. Big rain years like we had recently can leave unpaved island roads impassable, making it difficult or impossible to access our field sites. Flexibility is the name of the game on islands – you have to roll with the punches and do what you can when you can. But logistical challenges can also be fun. I’ve hopped around Santa Cruz Island via helicopter, flown across the channel in a four-seat plane, been salt sprayed on skiffs and taken countless boat rides all in search of rare plants. There’s no shortage of adventure on the islands!

What has surprised you about working with and learning more about rare plants?

It has been such an honor to focus on rare plant conservation for the last seven and a half years. One thing that has surprised me about rare plants is what a great tool they are for engaging the public in conservation efforts. We all love an underdog and rare wildflowers are easy to love, but some people also wonder why something so uncommon could be important to preserve. However, they can also provide an introduction to conservation by connecting people to a sense of place and what makes that place special. I was working on a front country trail in Santa Barbara a few years ago when a woman stopped to ask my team what we were doing. When we told her that we were mapping rare plants and told her a little about the multiple rare plants along the trail, she was overjoyed! She said this was her favorite trail and she couldn’t wait to tell her friends how special it was. We’ve had a lot of positive interactions with people in the field over the years and for those we meet elsewhere, we try to make the case that just because something is uncommon doesn’t mean it is unimportant.

What advice would you give to those who wish to learn more about how they can help save imperiled plant species?

There are so many ways that people can help rare plants and when you help rare plants, you help all native plants. Visit your local botanic garden and consider volunteering or donating if you’re able. Becoming a member provides sustaining support for people who focus on conservation. Go for a hike with friends or family and support the preservation of wild spaces. Plant native plants in your yard at home. Even if you plant common species, you’re still helping all native plants by supporting healthy pollinator communities. And I would encourage people to support conservation initiatives at the state and local level with their voices and their votes. We need conservation-minded folks at all levels of government to support regulations, legislation and funding to help us save plants. We can all be a force for rare plant conservation, whether our actions are big or small.

-

A rainbow on Santa Cruz Island. Photo credit: Heather Schneider. -

Setting up and reading demography plots for the federally endangered soft-leaved paintbrush (Castilleja mollis) on Santa Rosa Island. Photo credit: USGS. -

A helicopter approaches to take Heather to her next rare plant survey location on Santa Cruz Island. Photo credit: Heather Schneider.

Conservation News & Highlights

The Center for Plant Conservation’s National Office team and our network of Conservation Partners have been hard at work to advance our shared mission to save plants from extinction.

From CPC hosting our first-ever Native Plant Summit event and The Huntington facilitating an educational cryopreservation workshop, to new conservation-focused publications, our network continues to make meaningful strides to safeguard the rare and endangered plants of North America.

Read on for a round-up of the latest conservation events, news, and highlights.

2023 Native Plant Summit

Last month, CPC was thrilled to present its inaugural summit event, Unleashing the Power of Native Plants: A Resilient Future for Our Planet, which took place in Boston, MA, at the renowned Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The summit served as a platform for esteemed experts, professionals, and advocates from related fields to come together and discuss the importance of protecting and conserving native plants and their habitats as well as the pivotal role of plant species in establishing sustainable responses to global environmental crises.

CPC was honored to host distinguished scientists and conservationists from throughout its nationwide network of botanical organizations for a keynote presentation and panel discussion during the summit to share insights into this conservation model. The event’s keynote speaker, Dr. William (Ned) Friedman, Director of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University and Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University, was joined by an expert speaker panel including Dr. Emily E.D. Coffey, Vice President of Conservation & Research at Atlanta Botanical Garden; Wesley Knapp, Chief Botanist of NatureServe; and Dr. Lucinda McDade, Executive Director & Judith B. Friend Director of Research at California Botanic Garden.

The lively panel discussion highlighted the critical urgency, challenges, and opportunities in our network’s shared goal to save plants from extinction, with an overarching theme for success: collaboration. By working together and developing partnerships—with fellow conservation organizations, federal agencies, funders, plant enthusiasts, and more—we can amplify our efforts and save more plants than would ever be possible alone. CPC looks forward to hosting future summit events in 2024 as part of our 40th anniversary celebrations.

CPC is grateful to our network of plant conservationists from 74 world-class botanical gardens, arboretums, and other plant-focused organizations that collaboratively work to save the 4,400 most rare and endangered plants of the United States, its territories, and Canada, throughout their native range.

This event was generously sponsored by:

Corient

Garden Club of the Back Bay | Beacon Hill Garden Club | The Garden Club of Brookline | The Garden Club of Buzzards Bay | The Bennington Garden Club | Cambridge Plant & Garden Club | Chestnut Hill Garden Club | Cohasset Garden Club | Garden Club of Dublin | Fox Hill Garden Club | Boston Junior League Garden Club | Little Compton Garden Club | Milton Garden Club | The Garden Club of Mount Desert | Nantucket Garden Club | Noanett Garden Club | North Shore Garden Club of Massachusetts | Piscataqua Garden Club | Worcester Garden Club

-

Panelists (left to right)Dr. Emily E.D. Coffey, Wesley Knapp, Dr. Lucinda McDade, and Dr. William (Ned) Boston Friedman at CPC's inaugural Native Plant Summit hosted at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, MA, in October 2023. -

Dr. Carlos L. de la Rosa, CPC President & CEO. -

Summit Keynote Speaker Dr. William (Ned) Friedman).

Cryopreservation Workshop at The Huntington

-

Staff and participants at The Huntington's 2023 cryopreservation workshop. Photo courtesy of The Huntington. -

2023 cryopreservation workshop at The Huntington. Photo courtesy of The Huntington. -

Staff and participants at The Huntington's 2023 cryopreservation workshop. Photo courtesy of The Huntington.

Recent Publications

San Diego Thornmint (Acanthomintha ilicifolia) Populations Differ in Growth and Reproductive Responses to Differential Water Availability: Evidence from a Common Garden Experiment. Plants 2023, 12, 3439.

Heineman, K.D.; Anderson, S.M.; Davitt, J.M.; Lippitt, L.; Endress, B.A.; Horn, C.M.

The Center for Plant Conservation (CPC) collaborated with the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s plant conservation team to analyze data from a common garden experiment where plants of the federally threatened San Diego thornmint were subjected to water stress. The study found that plants grown from seeds collected at populations with higher annual rainfall created more seeds, especially under water stress, than plants grown from seed collected at drier locations. The seed production of this species is of particular interest to CPC because San Diego thornmint will be one of two species that receives detailed genomic analysis as part CPC’s new IMLS-funded seed bulking study.

Identifying predictors of translocation success in rare plant species. Conservation Biology, 2023

Joe Bellis, Oyomoare Osazuwa-Peters, Joyce Maschinski, Matthew J. Keir, Elliott W. Parsons, Thomas N. Kaye, Michael Kunz, Jennifer Possley, Eric Menges, Stacy A. Smith, Daniela Roth, Debbie Brewer, William Brumback, James J. Lange, Christal Niederer, Jessica B. Turner-Skoff, Megan Bontrager, Richard Braham, Michelle Coppoletta, Karen D. Holl, Paula Williamson, Timothy Bell, Jayne L. Jonas, Kathryn McEachern, Kathy L. Robertson, Sandra J. Birnbaum, Adam Dattilo, John J. Dollard Jr., Jeremie Fant, Wendy Kishida, Peter Lesica, Steven O. Link, Noel B. Pavlovic, Jackie Poole, Charlotte M. Reemts, Peter Stiling, David D. Taylor, Jonathan H. Titus, Priscilla J. Titus, Edith D. Adkins, Timothy Chambers, Mark W. Paschke, Katherine D. Heineman, Matthew A. Albrecht.

This article emerged from one of the component databases that now makes up the CPC Reintroduction Database, the REDCap database compiled by Matthew Albrecht and Oyomoare Osazuwa-Peters from Missouri Botanical Garden. The work contains important insights about the predictors of translocation success including that founders size (the number of plants planted) and habitat quality strongly influence reintroduction outcomes.

National Collection Spotlight: Cedros Island Oak

Cedros Island Oak (Quercus cedrosensis) is an imperiled oak species native primarily to Cedros Island in Baja California, Mexico, with one population occurring in San Diego, CA, at Otay Mountain. Major threats to this species include drought, wildfire, and border activitis. Oaks are exceptional species, meaning they cannot be stored using traditional seed banking methods, and are often conserved in living collections or other forms of long-term storage (such as cryopreservation). In 2017, only one individual of Quercus cedrosensis was known to be held ex situ in conservation collection.

Now, Quercus cedrosensis is secured in the CPC National Collection at San Diego Botanic Garden (SDBG), San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, California Botanic Garden, and The Huntington. Genetic material from this species at the Otay Mountain population has been collected in the form of cuttings and a few acorns, grown as a living conservation genebank by San Diego Botanic Garden with seedlings held in their nursery and distributed to The Huntington. Seeds from this species are hard to come by, with many wild individuals producing little to no acorns, making cuttings a helpful tool for conservation collections.

Learn more about conservation actions taken for Cedros Island Oak on its National Collection Plant Profile and help support critical conservation work for this species with a Plant Sponsorship. This species is part of CPC’s 40th Anniversary Campaign! In celebration of our 40 years of saving plants from extinction, we are raising funds to sponsor 40 National Collection species, including Cedros Island Oak. For every $5K raised per plant species, our Board of Trustees will provide $5K in matching funds to bring the species to the full sponsorship level of $10K–growing the impact of your gift in support of rare and endangered plants. Learn more about our 40th Anniversary Campaign.

As Seen on CPC’s Rare Plant Academy: Raising Peas in Rising Seas: How an increase in soil salinity affects seed germination and seedling survival of the Keys partridge pea

The Florida Keys, like other low-lying islands, are especially threatened by sea level rise. For island endemic species like the Keys partridge pea (Chamaecrista lineata var. keyensis), this threat could be catastrophic. The only known remaining populations of the Keys partridge pea are found within the imperiled pine rockland habitat on two islands of the Florida Keys. As a consequence of sea level rise, soil salinity levels are anticipated to rise as well, first in areas closer to the coast and eventually further inland. More frequent and higher storm surges are also predicted, which will temporarily inundate parts of the islands in saltwater.

In this video, recorded during the 2020 CPC National Meeting for the Rare Plant Academy, Sabine Wintergerst discusses research at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden aimed at discovering how sea level rise and subsequent soil salinity increase affect seed germination and seedling establishment. Results show that seedlings are especially threatened by storm surges, but further research is needed to investigate how well seeds and seedlings can recover as soil salinity is alleviated by precipitation. Knowing how these critical life stages of the Keys partridge pea are affected by an increase in salinity can inform the future population trajectory and help with management and restoration planning. Watch this talk and check out the Rare Plant Academy Video Library to watch many more videos and presentations about island species!

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Ways to Help CPC

Conservation Advocacy Initiatives

Be an advocate for rare plants like Kuawawaenohu (Alsinidendron lychnoides)!

Kuawawaenohu is a federally endangered, critically imperiled species endemic to mountainous wet forest habitats on the island of Kauai. Rare and endangered plants like kuawawaenohu are at risk of extinction due to a multitude of factors, from habitat development to climate change. Our network is working hard to #SavePlants, and you can help by using your voice. Be a rare plant advocate!

How can you help advocate for rare and endangered plants? Stay informed, contact your representatives about legislation related to conservation, and involve your friends and family!

On the Advocacy page of our website, you can find federal legislation in the U.S. that the CPC is tracking with a direct effect on rare plant conservation. You can also read CPC’s Position Papers and learn how you can help be your best endangered plant

Donate to Save Endangered Plants

Without plants, life as we know it would not be possible. Yet two in five of the world’s plants are at risk of extinction. More than ever before, rare plants need our help!

That is why all of us at the Center for Plant Conservation (CPC) are deeply grateful to have you as part of our conservation community. Your generous and unyielding support allows CPC and our network of world-class botanical institutions to make great strides in our shared mission to Save Plants from extinction.

Your gift ensures CPC’s meaningful conservation work will continue. Together, we save more plants than would ever be possible alone—ensuring that both plants and people thrive for generations to come. We are very thankful to for all that you do to help us Save Plants!

Donate to Save Plants Today!

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today