Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

November 2021 Newsletter

Recently, the CPC Board of Trustees adopted a Climate Change Position Paper. This document highlights the grave impacts of climate change on rare plants and outlines the solutions CPC supports to combat climate change. The impacts of climate change take many forms. In this issue of Save Plants, you can learn not only about how the Position Paper arose, but you can also learn about ways climate change is impacting Indigenous people and how the Native Plant Trust has developed a tool that will help identify climate-vulnerable and climate-resilient lands that hold large numbers of rare plant species. These Important Plant Areas are a way that we can visualize future conditions and make plans for the benefit of biodiversity. More and more, each of us has a story about how climate change has affected us personally. Our Conservation Champion Suzzanne Chapman’s story of watching her conservation collection floating in flood waters is enough to strike fear in any plant lover’s heart. Climate change is personal. It is important for us to tell our stories and to learn from others. One avenue is the online resources associated with the UN COP26 Conference and the Earth Project’s photo competition. These pictures truly capture stories about climate change that are worth more than a thousand words! We all need encouragement to gear up to take actions to mitigate this threat. Please join our efforts.

Wishing you continued health and safety,

Joyce Maschinski

CPC President & CEOClimate Change Position Paper | Center for Plant Conservation

At the Center for Plant Conservation (CPC), advocacy is an important tool in our efforts to save rare and endangered plants. Through advocacy, we can share and advance the mission and work of our organization, and we can use our collective voice to shape public policies, laws, and regulations in favor of imperiled plants. One way we do this is by developing position papers on topics relevant to our mission and plant conservation.

We are pleased to announce CPC’s new Position Paper on Climate Change, which was approved by the CPC Board of Trustees at the October 2021 Board Meeting. Collaboratively developed by the Board’s Advocacy Committee* and staff, the Climate Change Position Paper outlines the urgent need to protect rare and endangered plants which are facing unprecedented and dire consequences as a result of the global climate change crisis. As a community, we must take action and advocate the importance of protecting imperiled plants and the environment. The Climate Change Position Paper will give our organization the foundation needed to do just that.

What was your path to becoming CPC Board members and working to conserve native plants?

Lindsay: The mission of the Center for Plant Conservation is to save rare plants and their endangered ecosystems. Diana and I came to the CPC Board with a love for plants and having backgrounds in many organizations involving plants and advocacy. We both have held leadership positions in The Garden Club of America; I was former Chairman of the GCA National Affairs and Legislation Committee, and Diana was on the same Committee as well as on the Conservation Committee as a Vice-Chairman for Partners for Plants. I became Chairman of CPC’s Advocacy Committee in 2017.

Committee members are keenly aware of the need for advocating for imperiled plants and the urgency for action specifically relating to climate change, the most critical issue of today. Climate change impacts every aspect of our world and profoundly affects the existence and even survival of species and ecosystems. CPC’s goal is to prevent plant extinction and our objective is to bring climate change to the forefront of legislation, policy making, and educational efforts to address this global problem.

What is a Position Paper?

Diana: For CPC, a Position Paper is not a statement about a specific piece of legislation, but a general framework of ideas that address an issue with a consistent viewpoint that supports our advocacy efforts in saving plants. A Position Paper covers a specific topic which CPC determines to be of critical concern. By creating such a document, CPC can use it as a basis for timely advocacy around legislation that aligns with the CPC mission.

Why was there a need for a Climate Change Position Paper?

Lindsay: CPC has a Position Paper in support of the Endangered Species Act and protection of Threatened and Endangered Plants. However, climate change is an overarching factor that affects our planet today in multiple ways, including extreme weather events, wildfires, coastal flooding, droughts, changing habitat requirements, altered plant hardiness zones, and loss of pollinators. Many rare, threatened, and endangered native plants have small population sizes and limited suitable habitats, making them particularly susceptible to extinction triggered by climate change. Higher temperatures cause native plants to experience more heat-related stress. Higher atmospheric carbon dioxide levels preferentially promote the growth of invasive plant species (1). While some animals are able to move when conditions become unfavorable, rooted plants are immobile and thus cannot as easily adapt to a quickly changing environment (2).

What was the process like developing the Climate Change Position Paper?

Lindsay: Working with people on the Advocacy Committee, such as outstanding botanical garden professionals Lucinda McDade and Christopher Dunn, helped us focus our endeavors. Diana developed the first draft with Lucinda, then I joined in, and Christopher added thoughtful edits to create the final CPC Climate Change Position Paper.

Diana: Ultimately, it required seven iterations with additions and corrections before the eighth and final version was agreed upon. The staff gave their input, the Executive Board needed to pass it, and finally, the entire Board voted in favor of passing and adopting the Position Paper.

Lindsay: What is wonderful about CPC’s Board is that, despite Trustees living in many different parts of the country—for instance, Diana lives in central California and I live in Virginia and South Carolina—we collaborate and are like-minded in support of CPC’s mission and initiatives like the Climate Change Position Paper.

Why is it important for CPC to lead advocacy initiatives?

Diana: Advocacy is a crucial tool in our organization’s toolbox for supporting or opposing legislation that affects the survival of imperiled plants. With our network of 68 Participating Institutions (PIs)—all dedicated to saving plants—CPC is a leading and respected voice in plant conservation. Our Position Papers offer an educational outline for communication and action.

What excites you about the future of CPC?

Lindsay: With its PIs and initiatives, CPC is a dynamic and exciting place to learn from leading botanists, directors of botanical gardens, and scientific National Office staff members such as President & CEO, Dr. Joyce Machinski, and VP of Science & Conservation, Dr. Katie Heineman. The Board at CPC is a committed group of mission-driven members. The future is bright for CPC.

References

(1) https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Plants/Climate

(2) https://extension.umd/resource/native-plants-and-climate-change

*Advocacy Committee Members: Lindsay Marshall, Diana Fish, Ruth Evans, Christopher Dunn, Lucinda McDade, Clark Mitchell, Barbara Millen, and Joyce Maschinski.

Changing Relationships to Keep Traditions with the Sioux

When we discuss climate change and its impacts on plants, we often think of heat, cold, and changes to the amount, location, and seasonal timing of rainfall. Sometimes we bring up its effects on relationships between organisms, such as when flowers bloom before pollinators are around to do their part in reproduction. We discuss how changes in plants impact resources for animals and other elements of biodiversity. But one important aspect is rarely brought up—the ways climate change influences our human relationships with nature.

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe has rich biocultural ties to the area once known as the Great Sioux Nation, which includes the current Standing Rock Sioux Reservation and beyond. The impacts of climate change on this heritage are illustrated by the prairie turnip (Psoralea esculenta), a salient ingredient in a stew served during an early summer festival. Reduced snow cover is causing the ground to freeze at greater depths and take longer to thaw, which leads to a later emergence of the turnip. The Sioux must alter their festival traditions—but how? Should they move the date of their celebration? Substitute the prairie turnip with another main ingredient? Or do without?

Shifts in plant phenology also impact the ability of the Sioux to prepare for seasonal change. Shadbush (Amelanchier) flowering has long been used as an indicator that shad are spawning in the rivers. However, shadbush is flowering earlier and is no longer a reliable indicator. Animals important to the Sioux are also changing—many community members have noted a reduction in the quality of bison fur and hide.

Christopher Dunn, Ph.D., Executive Director of Cornell Botanic Gardens, and a group of Cornell faculty and graduate students are working with the Sioux of North and South Dakota and other Indigenous peoples as they document and navigate climate-induced changes in their cultural and ecological relationships. A key project objective is to obtain a detailed understanding of the changes happening to the Standing Rock community, especially with ecological indicators such as the shadbush. The desired outcome is to determine a strategy to find workable climate adaptations, including new plant or animal indicator species, that will allow this community to maintain its traditional ways of living on the land.

The Cornell project team is large and varied. Critically, it includes members and leadership of the Sioux community, as well as faculty and students at Standing Rock’s Sitting Bull College. The partners from Cornell largely consist of university faculty in the fields of natural resources, social sciences, avian ecology, and the biophysical aspects of climate and climate change. Their roles relate to each person’s expertise: collecting hard scientific data, conducting workshops and interviews with members of the community, and developing works of art that depict issues, challenges, and the promise of hope.

When beginning a partnership with Indigenous communities, the first challenge is to establish trust. This takes time and a lot of listening. The Cornell team members realize and demonstrate that their role is to help, not to dictate or direct. For this project, a second challenge lies in understanding the magnitude, speed and impact of the environmental changes that are occurring. Recent years have seen significant progress with respect to a third challenge: the tendency of western universities and institutions to devalue this work as not sufficiently academic or important. Dr. Dunn finds it “enormously gratifying to see a significant increase in conferences, peer-reviewed publications, funding opportunities, and public garden programming that explicitly relate to and support greater collaboration between western and Indigenous ways of knowing.” Many international conventions, platforms, and agreements now acknowledge the impacts of the climate crisis on Indigenous and other vulnerable communities.

Increasing awareness and support presents another way for Cornell Botanic Gardens to help with biocultural conservation. Their new Strategic Plan, mission, and vision clearly articulate the centrality of biocultural diversity in much of what they do. Interpretation of plants and landscapes adds important cultural elements to the stories the plants tell, going well beyond the usual topics of ecology, evolution, or taxonomy. As Executive Director, Dunn is proud of the progress his garden has made. “At Cornell Botanic Gardens, we explicitly connect visitors to the human and cultural importance of plants. Botanic gardens generally tend to focus on plant conservation for the plants’ sakes. But gardens (and other natural history organizations) also need to conserve the cultural stories, cultural heritage, and languages that are equally threatened.”

He believes that fostering a greater understanding of local Indigenous communities—and, ideally, establishing partnerships with them—is something that all botanic gardens can and should do. If a garden does not have the capacity to engage directly, it can certainly do more in the areas of interpretation, education, and public programs. Garden staff should be not only stewards of plants and landscapes—they must also recognize and articulate the cultural history and significance of the plants and landscapes. Those stories are our human stories.

Saving Land to Save Plants in a World of Change

For over a hundred years, entities in New England have been working to conserve land in order to conserve nature. While the acreage or quantity has been adding up, the quality of the land—how effective it is at conserving biodiversity—has been unknown. Recently, Michael Piantedosi, Director of Conservation, and the staff at the Native Plant Trust (NPT) realized they were in a good position to examine the quality of the region’s land conservation efforts. The NPT team knows plant diversity, which is the foundation for overall biodiversity. For decades, NPT has gathered information on rare plants across New England and shared it with the appropriate Natural Heritage Program in each of the six states. This work has equipped the states with solid knowledge of their rare plant ranges, status, and threats.

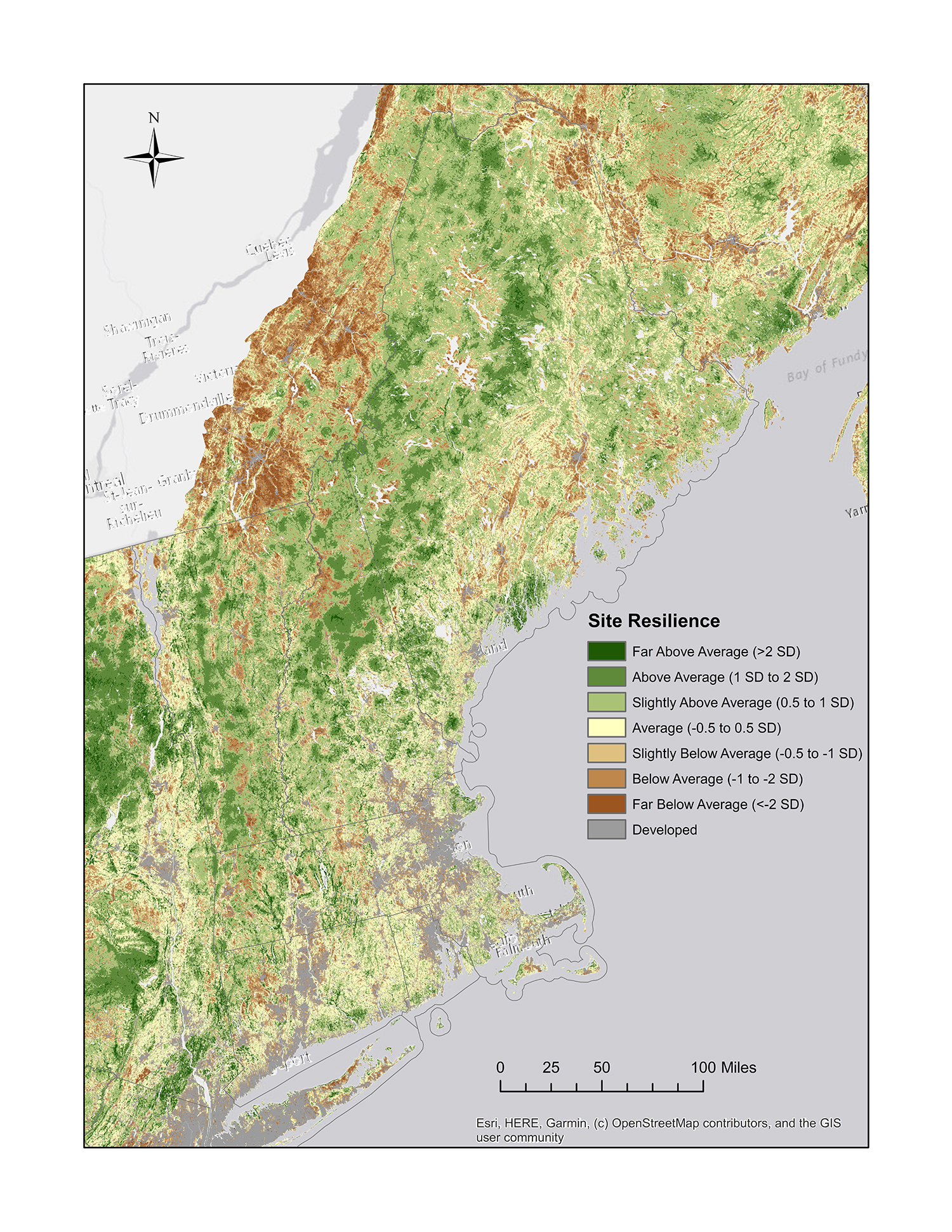

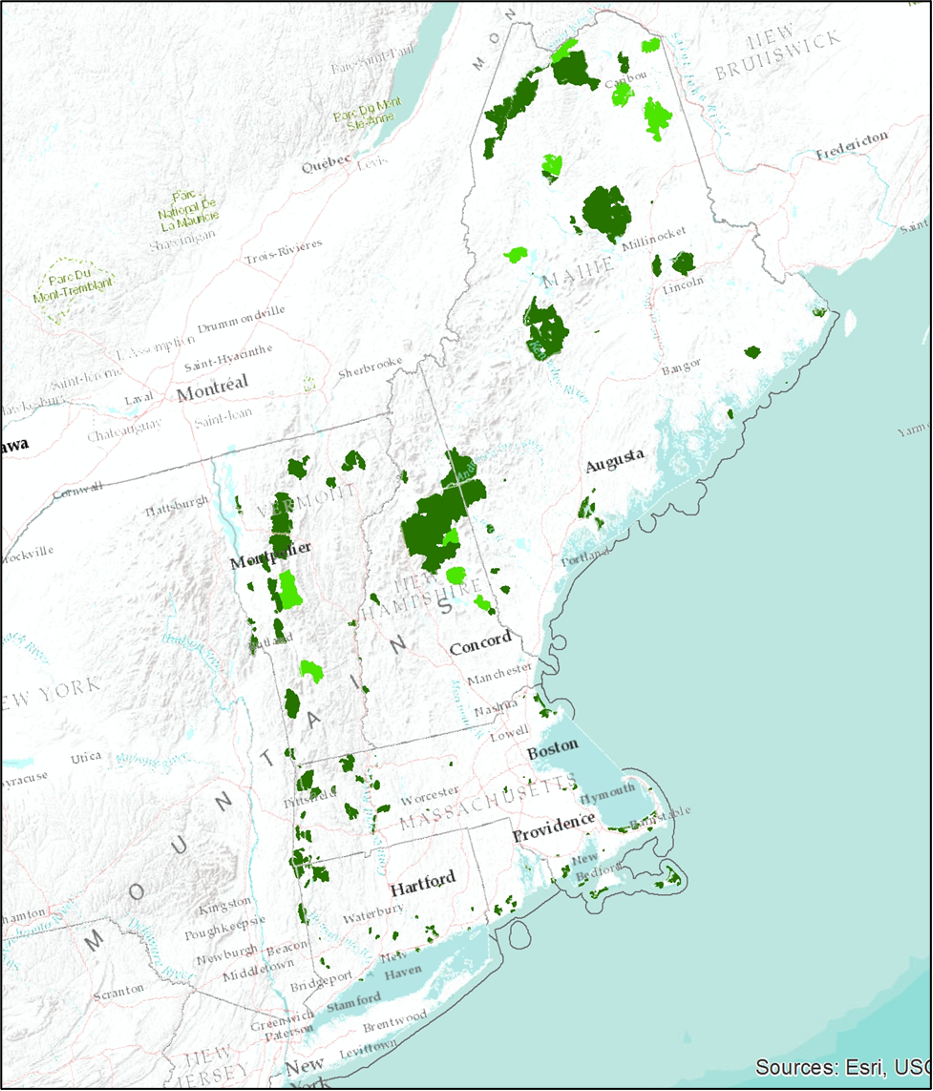

NPT partnered with the Nature Conservancy (TNC) to combine data and expertise, strategically applying spatial data in maps to account for where and how different ecosystems would—and would not—be altered by climate change. Armed with a robust plant dataset, Michael and the NPT team were able to identify Important Plant Areas (IPAs), which are regions with significantly higher populations of rare plants than neighboring areas. Key resources developed by TNC included habitat maps that allowed the team to focus on habitats rather than species, models of habitat climate resiliency (how features in the landscape might buffer species from the impacts of climate change), and data compiled on the conservation status of lands in New England.

Using these data, the team was able to assess the state of biodiversity conservation in New England and compare those results to 2030 goals set for the region (side bar). In the end, the two entities created the “Conserving Plant Diversity in New England” report and accompanying mapping tool. Overlaying various information layers in the mapping tool reveals what percent of each habitat type falls in protected areas, how much of that preserved habitat is also climate resilient, how IPAs are distributed across the habitats, and how the IPAs are protected. This tool can be used by land trusts, public officials, and others to identify lands that would most benefit biodiversity conservation efforts into the future.

After looking at the protected status and climate resiliency of habitat and plant diversity, the report team looked at the percentages of land secured to where New England was doing well and where needed more conserving. National and international guides provided benchmarks for comparison to measure success at reaching specific conservation goals. President Biden’s America the Beautiful Initiative recognizes the Global Deal for Nature’s recommendation to protect 30% of the world’s ecosystems by 2030 while the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC) recommends conserving 75% of the most important areas for plant diversity and protecting 15% of each vegetation type. Tailoring New Englands goals to these larger standards, the team created targets to parallel the GSPC targets with a timeframe of 2030: 1) At least 5-15% of each habitat protected and at least 30% secured against conversion. At least 75% of the securement on climate resilient land, and 2) At least 30% of each climate-resilient area with the highest rare plant diversity (IPA) protected and at least 75% of each IPA secured against conversion across habitats and states.

The results held their share of ups and downs, as well as surprises. One of the ecosystem types, coastal plains, was found to be both susceptible to development and occurring in areas of low climate resiliency, making it particularly vulnerable. Fortunately, a portion of this habitat type is conserved on climate-resilient land. Although forests cover 86% of the landscape, only one of the 10 forest types was found to meet the regional goal of being 15% protected. An additional 2 million acres of climate-resilient forest is needed to meet that goal across all forest types. Michael was encouraged and surprised by the fact that the IPAs were proportionally distributed among habitat types, not just in patchy “specialty” habitats like alpine grasslands or bogs—indicating that efforts to conserve all IPAs would generate great progress in conserving most of the habitat type.!

As the team disbursed and promoted the report, they learned how much people had been looking for such a tool. Land trusts—non-profits that acquire and manage land and conservation easements—want to conserve ecologically important land, and many had been contemplating how to measure this. Now they have that ability. Michael has been busy sharing the report with every land trust in the region, local agencies, and local and national politicians, as well as training others on how to use the mapping tool. The report’s positive reception is a sign of hope for plant diversity as people gear up to take action.

Although NPT does not use land acquisition as a primary tool, the report will guide their actions in other ways. The IPAs identified will be good sites for surveys and inventories to monitor diversity. The tool will also help with selecting rare plants to target for seed banking or other ex situ protections. For instance, for a species with nine out of ten occurrences on land that is climate-vulnerable or at high risk of development, those nine populations would be high-priority seed banking targets. The maps can also help the team plan experiments in assisted migration, by identifying plants that have at-risk populations but suitable habitat nearby on climate-resilient land.

The report team views their product as living document, with an electronic format lending itself to additions and edits. Michael is looking forward to examining the data at a finer scale, taking a look at microhabitats or more precisely defined habitat types. And, of course, the team will examine progress in 2030 to determine how close the six states come to meeting the ambitious goals set in the report.

The strength of Natural Heritage Program plant data across the U.S.–along with TNC’s widespread efforts to conduct conservation land gap analyses and map climate resiliency–will allow the analyses behind the Conserving Plant Diversity in New England report to be recreated in many regions. Learn more about the data used in this report below.

Rare Plants – NPT has worked with partners in its New England Flora Committee to keep rare plant rankings updated, most recently in a 2012 update to Flora Conservanda. Location data on the occurrences (or populations) of these rare plants is held in the Natural Heritage programs of each state.

Conserved Land – This project identified four levels of conservation status: 1) Protected for nature and natural processes (e.g., natural reserves, designated wilderness areas); 2) Secured for nature with management (e.g., National Parks); 3) Secured for multiple use, some of which may cause disturbance (e.g., national forests with logging or grazing lots); and 4) unsecured. The data came from a conservation land gap analysis in TNC’s Secured Land dataset.

Habitats – The Northeast Terrestrial Habitat Map, which served as the key data source for habitats/ecosystems, delineates 43 unique habitat types across New England. The habitats are comparable to the NatureServe ecological system classification.

Climate Resilience – TNC devised an approach for assessing based on enduring geophysical characteristics of the land. They score every pixel of mapping images to account for diversity of microclimates and connectedness between patches of an ecosystem and key landscape features like water sources. This system allows TNC to identify areas of high and low resilience to ecosystem changes resulting from a changing climate.

Development Threats – To estimate the threat of conversion from natural to developed lands, the report team used a Land Transformation Model that was developed by the Human-Environment Modeling and Analysis Laboratory at Purdue University to determine land likely to be developed by 2050.

Suzzanne Chapman

Our Conservation Champion, Suzzanne Chapman spent many of her working years dedicated to saving plants. Working at Mercer Botanic Gardens, she had many opportunities to be a hero for rare plants facing threat from climate change. Her great love of nature and of plants continues in her retirement, where she continues to share the message that we (humans) are an integral part of nature.

Congratulations on your recent retirement! What are you looking forward to in this new life chapter?

I’ve just moved to a ‘new’ home and am busy working on it. Now that cooler temperatures are with us in Houston, I’ve been moving potted plants and dividing plants from the old garden to install in my new garden. I now have more space, so I’m thrilled to remove lawn, add garden beds, and amend the soil with some wonderful local compost when I plant more native pollinator plants. This summer, as a volunteer, I met up with Anita Tiller and the Mercer Botanical Center (MBC) interns to forage for seed of Asclepias viridis in a local park near me. I just recorded my new garden as part of the Homegrown National Park, a scheme designed by professor/author Doug Tallamy to show how much home gardens can contribute to the collective green space to support plants and wildlife biodiversity.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

Growing up in England, it is innate to feel connected to the outdoors and nature. We lived in a small town with plenty of green space, woods with bluebells and primroses in springtime, and trees to climb. Some of the words I remember using as a child are Syringa and Rhododendron, the botanical names for Lilac and Azalea. My Nana encouraged me to play in the garden and pick her tulips.

What was your career path to Mercer Botanic Gardens?

I came from an accounting position, then was laid off in one of the ‘leveraged buyouts’ that occurred during the 1980’s. I looked at my options and knew I wanted something more personally fulfilling—and I loved gardening. I started to volunteer at Mercer in the greenhouses on Saturdays, while attending Houston Community College part-time for an AS in Horticulture and working full-time at two jobs. I was hired part-time by John Fairey at Peckerwood Garden—now The John Fairey Garden in honor of its founder—to assist with propagation (primarily of conifers) and the garden’s seed distribution program. I was still volunteering at Mercer, which was much closer to home, and I took a full-time position as gardener there in 1994. In my 27 years at Mercer, I was greenhouse manager, horticulturist, and volunteer coordinator. When I retired, I enjoyed the position of botanical collections curator. Surprisingly, my accounting background was very useful, as timing and numbers are critical for greenhouse operations with propagation of plants by seed.

In your experience, what are some of the pressing conservation needs related to Texas’ rare and native plants?

Communication and education of the public is one pressing need, since most Texas land is privately owned. Education of developers is another, since the population continues to expand dramatically in the Houston area. We are in a sub-tropical floodplain, and many of the trees and natural areas we enjoy are still being cleared and paved over. It drives me crazy that new commercial spaces get surrounded by rows of Ligustrum shrubs when we have native plant options.

Remove the word weed from so many common names of wild native plants! We need more engaging terms to encourage folks to try growing natives in their home gardens as ornamentals.

How did the effects of climate change impact your work at Mercer Botanical Gardens? What successes and challenges did you encounter?

With Mercer being adjacent to Cypress Creek, our challenges were definitely the floods. The winter of February 2021 was a shock to the system, but remarkably most plants came through strong! The extremes are always an issue. The successes are that we have become very well-prepared and resilient to the floods.

Better weather reporting contributes to MBC’s planning. We have a whole building generator to protect the rare refrigerated/frozen stored seed bank. The MBC herbarium is housed on the second floor for safety, and the building is being secured with hurricane shutters.

Mercer recently was awarded grants to move the vulnerable conservation nursery from its current remote greenhouse location to the ‘backyard’ of the MBC, where plants will be easily accessible and above flooding potential. During the 2017 Hurricane Harvey, flood waters floated plants and nursery tables over the existing nursery area—despite its surrounding 10’ fence! Most plants floated and settled to the ground when the water receded, and others were retrieved from the tree line further away. Luckily, we did not lose a single plant.

What conservation project/initiative are your particularly proud of from your time at Mercer Botanic Gardens?

The R.A. Vines SBSC Herbarium was a great project. Three staff with 20+ volunteers and interns moved a collection of ~50,000 herbarium specimens to the MBC. We boxed, froze, unboxed, filed, and refiled as names or families changed. In just over two years, we completed a basic digitized inventory of the collection for the first time. Hurricane Harvey made the project even more memorable. We had to move our work upstairs from a gutted ground floor until repairs could be made.

The staff, volunteers and interns have accomplished some amazing work during my time at Mercer and continue to do so. One of the latest projects has been working with BRIT and the Global Genome Initiative for Gardens, collecting living tissue and storing herbarium specimens at Mercer. Another is Mercer’s involvement with the Global Conservation Consortium for Oak. Personally, I am thrilled to have known some folks for 25+ years as volunteers who are great friends outside of work. The more folks we touch through gardening and nature, the word gets out to protect plants and biodiversity everywhere.

In the early 2000’s, Anita Tiller brought the Millennium Seed Bank (MSB) project to Mercer through Michael Eason from the Ladybird Johnson Wildflower Center. Michael Eason is the author of ‘Wildflowers of Texas’ and conservation botanist for Texas Flora – Facebook, and San Antonio Botanic Garden. At that time, as a volunteer, I and others accompanied Michael to East Texas for many seed collecting forays. Staff from Kew also joined us, and this gave me a perfect opportunity to reconnect with Janet Terry while on vacation visiting family in England. We were given a behind the scenes (or should I say underground) tour of the MSB at Wakehurst Place/Kew, a real treat!

What advice do you have for newcomers to the field of plant conservation?

I am excited by the enthusiastic young folks entering the field of plant conservation. Mercer has had some amazing interns. During the COVID pandemic in 2020, one intern working from home designed signage and prepared a guide to grasses for the HCP4 Prairie Dawn Preserve. It’s very rewarding to work with like-minded folks, co-workers, volunteers, interns and friends. I love to to see that spark in someone new to plants, gardening and conservation.

Connect with everyone you can! Even with COVID, we attended fabulous online meetings to keep up to date on projects and meet new folks. One of the rewards from last year was to see more folks with their kids getting back outside and learning to garden!

What has it meant to you to be a member of the CPC network? How has CPC supported your work?

It’s exciting to be part of a network of people working in the same field and see their successes. CPC provides opportunities to share best practices and techniques for working with rare plant propagation. Real-time information is increasingly available to everyone online, and we enjoy more collaboration among groups. Thanks to the involvement and encouragement of CPC conservation work in addition to other programs at the MBC, our needs have grown from one staff botanist to a full-time staff of four, with seasonal interns and over 20 volunteers.

What advice would you give to the public who want to learn more about how they can help save imperiled plant species?

We need to feature how amazing plants are, and that they are crucial to all life on the planet. Plants provide the habitat that supports all the charismatic endangered wildlife. We are an integral part of nature, not just viewing it from the sidelines!

Get involved with local public gardens and look at their conservation programs. At Mercer, check out the Endangered Species Garden, and consult the conservation interpretive signage and educational booklets for details on protecting plants.

In your home gardens, save some space for the wild to sneak in. Keep native trees, ditch the lawn, save the leaves, learn the plants, plant for pollinators, feed the birds, and embrace the wilderness close at hand.

-

Neches River Rosemallow (Hibiscus dasycalyx) plant at east Texas preserve site, July 2017. Photo by Suzzanne Chapman courtesy of Mercer Botanic Gardens. -

Suzzanne Chapman at the dedication of support for the Endangered Species Garden by the Kingwood Garden Club, June 2004. Photo courtesy of Kingwood Garden Club -

Closeup of Large-fruit Sand-verbena (Abronia macrocarpa) at Mercer growing in sandy soil. Photo by Greg Wieland.

UN Climate Change Conference

The 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) is currently underway in Glasgow, Scotland, bringing together world leaders to commit to urgent global climate action. The adverse effects of climate change impact all life on Earth, including imperiled rare plants. As a lead-up to the COP26, CPC President & CEO, Joyce Maschinski, partnered with the Earth Project to share about our network’s plant conservation initiatives, and how swift action must be taken to safeguard rare and native plants from the threats of climate change. Watch the video and hear from other leading conservation organizations here.

As Seen on Rare Plant Academy

Alpine ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to climate change. Learn how the Denver Botanic Gardens is seeking to protect rare species from these regions, banking seeds from multiple Alpine populations by maternal line, performing germination trials, and growing seedlings to be reintroduced. Plants are also added to the living collections at Denver Botanic Garden and the Betty Ford Alpine Botanic Gardens to further preserve these rare species.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Employment Opportunities

MS Position Available

USDA-NRCS: Deciphering Diversity for Landowners

South Dakota State University

Department of Natural Resource Management

One funded Masters graduate research position is available beginning in Spring semester 2022 in the

Department of Natural Resource Management under the supervision of Drs. Maribeth Latvis and Lora

Perkins for students interested in conservation and management of biodiversity, ecosystem services, soil

heath, and stakeholder engagement and education.

This graduate position is part of a collaboration among the SDSU Native Plant Initiative, The Nature

Conservancy, and the U.S. Geological Survey with funding from USDA-NRCS. Overall project objectives

include multidimensional assessment of biodiversity, soil health, pollinator response, and development

of educational tools for land management.

Post-Doctoral Researcher Position Available

USDA-NRCS: Deciphering Diversity for Landowners

South Dakota State University

Department of Natural Resource Management

A new position for a postdoctoral research associate is available with the Native Plant Initiative at South

Dakota State University (SDSU). This position is part of a collaboration among the SDSU Native Plant

Initiative, The Nature Conservancy, and the U.S. Geological Survey with funding from and in

collaboration with the USDA-NRCS. The project will use experimental plots at Oak Lake Field Station (26

miles NE of Brookings, SD) to examine multidimensional aspects of biodiversity and their impact on soil

health and pollinators.

Georgia Audubon is hiring a Habitat Program Restoration Coordinator to assist in the implementation of habitat restoration and related conservation programming under the direction of the Habitat Program Manager. To learn more or to apply, please click on the job description below.

The successful candidate will be hired as a full-time, 40-hour per week exempt employee. The employee is expected to work 40 hours per week, including occasional weekends or weeknights. Starting pay will be in the low to mid $30,000 annually, including paid time off. Group health insurance, participation in a voluntary retirement plan, and professional development opportunities will be available, including participation in the Georgia Audubon Master Birder program.

This application period will remain open until the position is filled.

Apply here.

Ways to Help CPC

Support CPC By Using AmazonSmile

As many of us are now working from home and relying on home delivery more and more, we want to remind you that you can keep your home stocked AND Save Plants. If you plan to shop online, please consider using AmazonSmile.

AmazonSmile offers all of the same items, prices, and benefits of its sister website, Amazon.com, but with one distinct difference. When you shop on AmazonSmile, the AmazonSmile Foundation contributes 0.05 percent of eligible purchases to the charity of your choice. (Center for Plant Conservation).

There is no cost to charities or customers, and 100 percent of the donation generated from eligible purchases goes to the charity of your choice.

AmazonSmile is very simple to use—all you need is an Amazon account. On your first visit to the AmazonSmile site, you will be asked to log in to your Amazon account with existing username and password (you do not need a separate account for AmazonSmile). You will then be prompted to choose a charity to support. During future visits to the site, AmazonSmile will remember your charity and apply eligible purchases towards your total contribution—it is that easy!

If you do not have an Amazon account, you can create one on AmazonSmile.

Once you have selected Center for Plant Conservation as your charity, you are ready to start shopping. However, you must be logged into smile.amazon.com—donations will not be applied to purchases made on the Amazon.com main site or mobile app. It is also important to remember that not everything qualifies for AmazonSmile contributions.

So, stay safe inside, and when ordering online, remember you can still help save plants. Please feel free to share this email with your friends and family and ask them to select Center for Plant Conservation.

Thank you all for ALL you do.

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today