Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

November 2020 Newsletter

Landscapes under our care ranging in scale from small gardens to large public landscapes and vast natural areas are the way many of us connect with nature. Without question, all of us can experience great emotional and physical health benefits when we connect with nature. Healthy landscapes and ecosystems are also essential for rare plant species to thrive. In this November issue of Save Plants, we feature CPC network conservation partners, who have incorporated lessons from nature to design intentional, sustainable, water-wise, healthy gardens and public landscapes, and those who have designed experiments in natural areas to help interpret and use nature’s lessons about resilience.

Wishing you and your families continued health and resilience,

Joyce Maschinski

CPC President & CEORestoring Ozark Landscapes at Shaw’s Nature Reserve Missouri Botanical Garden

It’s surprising how much work goes into managing ‘natural’ lands. Removing invasive plants, returning fire to the landscape, and encouraging other ecological processes interrupted by human action takes considerable labor and resources. Each growing season at the Missouri Botanical Garden’s (MBG) Shaw Nature Reserve, Mike Saxton (Supervisor, Ecological Restoration) and his team tackle the removal of herbaceous weeds that pop up on the landscape. It’s a challenge to remove them when they’re big enough to identify but before they have a chance to suppress native species or set seed. The work is unending: herbaceous plants are prioritized in the spring and summer, then in winter the team pivots to woody invasive plants. Sometimes restoring ecological processes such as fire is sufficient to facilitate the return of native habitats. At other times, more active restoration, such as seed addition, is needed. Land management requires a vision and a plan, and the staff who manage the Nature Reserve have one.

The property, located 35 miles west of Saint Louis, has lived several lives under the care of MBG. It began in 1925 as a 1,300-acre sanctuary to shield MBG’s exotic plant collections from the air pollution of the early 20th century. Following a stint as a traditional arboretum during which the land holding expanded by 1,100 acres, the land reached its true potential as Shaw Nature Reserve. The Nature Reserve is now managed to inspire stewardship of the environment through education, restoration and protection of natural habitats, and enjoyment of the natural world.

Transformed by circumstance and design, the property evolved from degraded farmland into a diverse mosaic of natural communities representative of the Ozark region. The location provided conditions amenable to conservation and interpretation of different regional habitats, though not all were present before European settlement. Design played an important role as well, with staff and volunteers working diligently to create, expand, and maintain the distinct habitats. Although much of the site maintained high levels of native biodiversity, many areas were heavily impacted by previous land uses. In highly disturbed areas, land managers were not bound by intact systems and were free to establish tallgrass prairie plantings that were not present at the site before European settlement. Director Quinn Long, Ph.D., points out that the 2,400 acres of the Nature Reserve offer a microcosm of the habitats found in the region, including woodlands, wetlands, savanna, dolomite glades, floodplain forest, and a stretch of the Meramec River. This variety provides valuable opportunities to support ex situ (offsite) collections or experiment with rare plant reintroductions.

Although no endangered or critically imperiled plants occur naturally at the Nature Reserve, Pyne’s ground plum (Astragalus bibullatus) is an example of a rare species that has benefited from experimental restoration. An ex situ population of Pyne’s ground plum is maintained on a glade at the Nature Reserve as part of an experiment, directed by Matthew Albrecht, Ph.D. (Scientist in Conservation Biology at MBG), to examine the impact of fire on the species. On the Nature Reserve, staff are able to control fire seasonality and intensity for the ex situ population – a task that would be incredibly challenging to undertake with natural populations of Pyne’s ground plum.

Understanding how fire impacts a rare plant reflects the staff’s central focus: to restore and understand ecological processes. Fires are known to be an important part of Ozark ecosystems, but their optimal frequency to achieve diverse management objectives is less clear. Prescribed fires undertaken by staff on the Nature Reserve are part of their efforts to manage for ecosystem health. For Mike and Quinn, this means maximizing representation of native species to promote resiliency.

Some of the land is still quite degraded and will not simply recover historic levels of native diversity with the removal of invasive plants or the reintroduction of fire. For each restoration project, the team consults historical records and reference plant communities in the surrounding area to guide their plant palette. Staff members spend substantial time collecting many of the seeds for restoration from the Nature Reserve itself. At times, seeds are brought in from the outside for uncommon species that may be compatible with the habitat but not yet present due to dispersal limitations. Instead of only conserving species conclusively known to occur on the site historically, the team strives to maximize representation of local diversity throughout the Ozark border region. As Quinn explains, “Even if we had a time machine to document the precise historical composition of plant communities at the Nature Reserve, we are operating in a very different, contemporary landscape.” This approach opens the door to introducing a rich array of native species, including experimental populations of rare ones like Pyne’s ground plum, or—perhaps eventually— reintroduction of species such as running buffalo clover (Trifolium stoloniferum) that may potentially have occurred on site historically.

Although ecosystem management is central to the mission, Shaw Nature Reserve is also a valued learning resource and was designated as a National Environmental Education Landmark by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior in 1972. A variety of amenities encourage the public to engage with nature. These include 17 miles of hiking trails, an interactive outdoor classroom space, formal outreach programs, and the Whitmire Wildflower Garden, which is one of the finest examples of native plant horticulture in the Midwestern US. The team aims to provide educational experiences that highlight the planning and work required to steward nature, in the hope that visitors to the Nature Reserve will bring new insights home and become active in promoting conservation throughout their communities.

The Power of Volunteers

Managing 2,400 acres requires many, many hands. Fortunately, in addition to staff, Quinn and Mike engage a community of dedicated volunteers in the Volunteer Stewardship Program. These volunteers don’t just participate in regular workdays with staff—they have the opportunity to take on a sense of ownership for individual stewardship units. Except for training and regular guidance, the excited (mostly retired) volunteers are largely left in charge of their acreage to remove invasive plants, collect and sow native seeds, and organize their own volunteer workdays. In the process, they become leaders and ambassadors for land stewardship, both on the Nature Reserve and beyond its boundaries.

The community-driven stewardship program promotes appreciation and stewardship, making a vital contribution to the Nature Reserve’s outreach programs. But it offers more than a place of learning and a sense of ownership—the participants achieve truly valuable results. Volunteers now manage 60 acres of the Nature Reserve, creating more time for staff to invest in other areas. It’s a win-win situation for volunteers, staff, and—most importantly—the Nature Reserve!

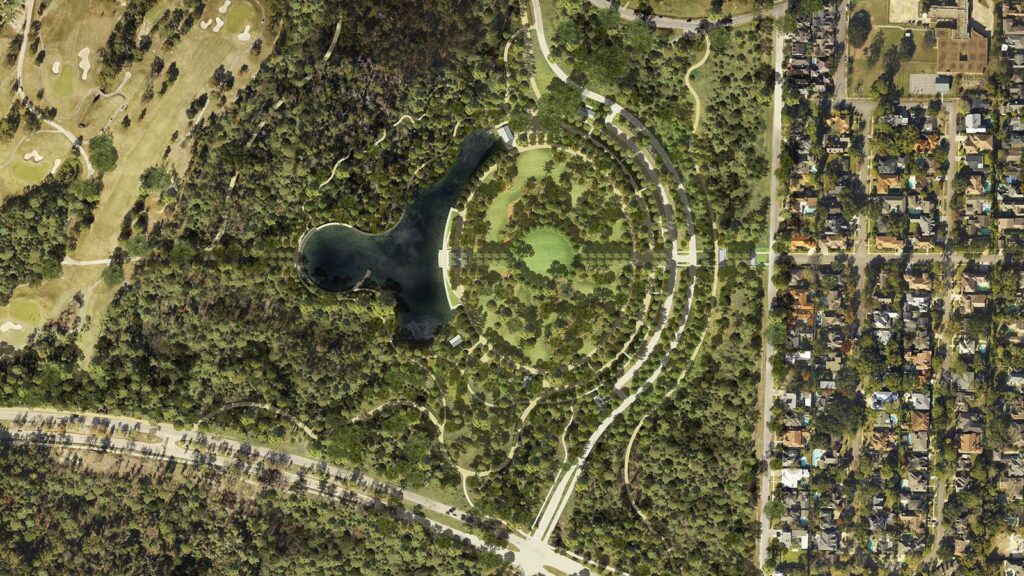

Ecology and Design for Houston’s Memorial Park Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects

Not too long ago, native aggressive yaupon holly thickly overgrew soggy ground in the Eastern Glades area of Memorial Park in Houston, Texas. What seemed to be a thousand mosquitoes lay in wait for the unwary. A serene and beautiful wetland, created by a geological fault line, was disrupted by desire line paths (unplanned, from repeated use) following the old roadways of Camp Logan, a World War I training camp. The Glades—clearings in the forest from tree mortality after Hurricane Ike and the subsequent drought—offered moments of relief from the oppressive weight of dense vegetation.

But a very different experience now awaits the visitor, brought to fruition by the staff at Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects (NBW). Through years of planning and work with various partners, NBW introduced a vibrant new feel to the Eastern Glades. Distinct, expanded neighborhood paths invite visitors in. Once inside, a feeling of immersion in wetland quiet is unaccompanied by hordes of mosquitos and persistently wet feet. With most of the yaupon and tallow trees gone, the Glades offer a sense of open airiness among oaks and towering pines.

The largest transformation is perhaps the 5.5-acre lake, where a vista opening to the west presents ever-varying encounters of sunsets and the movement of air and light across the water. The lake edge, accessible by boardwalk and two central terraces, is benched to create a zone of shallow water for planting. This zone is shaded by swamp lily, swamp milkweed, Texas spider lily, water hyssop, maidencane, and lizard’s tail—perfect habitat for frogs, hatchling fish, and the wading birds that prey on them. The lake has become a theater of nature that draws people in and connects them to what is real and observable—and often quite beautiful.

Implementation of this 100-acre project took place in two stages. To begin, East Memorial Loop was shifted to move the roadway closer to the edge of the park, opening an area for recreation, restoration of park ecologies, and storm water management. This was followed by construction of the glades, the lake, the boardwalks, and various amenities. Despite COVID-19 limiting NBW team travel from one of their central offices in Charlottesville, Virginia to their field office in Houston, the project was finalized in 2020 and opened to an excited public. With a happy client and an effusive public, NWBLA Senior Associate Jeff Aten rates this first major project of the Memorial Park Master Plan a success. “There is nothing quite so rewarding as seeing a place used in ways we imagined and in ways we could not have imagined, by people who seem genuinely thrilled.”

The project meets all of the guiding tenets of the master plan: to restore, consolidate, tend, reconnect, and enhance. Restoration is achieved with the creation of adaptive systems, such as bioretention and runoff capture, and implementation of a savannah ecology in the Glades’ islands of preserved vegetation. A shift in circulation orchestrated with the road redesign and creation of new social opportunities fall within the task of consolidation. The parklands are tended and enhanced through a number of project elements, including strengthening Houstonians’ connection to cultural assets such as Camp Logan history and improving a beloved 3 mile running loop. Linking storm water systems and providing an accessible entrance at Blossom Street build on the principle of reconnection.

At NBW, the landscape architects embrace a variety of projects at a variety of scales. A private or institutional garden design might include an existing or proposed building that would dictate certain constraints. But for the Memorial Park Eastern Glades, the landscape comes first and always will. As Jeff puts it, “The ecology, the cultural history, and the way in which the human visitor interacts with those elements lends richness to the push and pull of constraint and opportunity. This means the constraints have more to do with soils, sunlight, water, capacity, access, and maintenance, and less to do with how the landscape might ‘serve’ the building; and the opportunities have to do with how to find what is beautiful and essential and either preserve it or enhance it so that it becomes visible and apparent.”

The beauty of the elements, although central, is not the only message conveyed by the Eastern Glades. Visitors encounter conservation messaging in both interpretive signage and design. Signs throughout the project explain restoration work on native woodland islands between the glades and the Memorial Park Conservancy’s work to establish healthy forests and savannahs. Conservation and stewardship of the park’s resources are also reflected in the capture of runoff from parking lot and roadway in a series of low-slope bioretention channels that feed into the lake. Stored water can be drawn down to irrigate the lawns and native landscape of the Eastern Glades. This captured rainwater offsets millions of gallons of potable water that would otherwise come from the City of Houston.

No one person that can take credit for the design, construction, or funding of this project. It takes an incredible number of people working together to make something so amazing. Jeff Aten muses, “I think my favorite part [of the project] is reflecting on the collective that made this possible.” The Memorial Park Conservancy, the Kinder Foundation, the Uptown Development Authority, and the City of Houston all provided expertise, fund-raising, management, and input essential to making this project a reality. An outstanding group of volunteers formed an advisory EcoTech panel to support the Master Plan development, providing feedback on ideas about restoring various ecologies, the cultural and ecological history of the site, and management of various proposals through time. Soil scientists, ecologists, archaeologists, and engineers on the NBW team did deep dives into their focus areas. Everyone played a fundamental role in moving this project from master plan to concept design to implementation. It was through collaboration and commitment to design excellence that all of this was made possible.

This incredible group is moving on to implement more of the Memorial Park master plan. The Land Bridge and Prairie project is now under construction, with earthwork underway and precast tunnel sections ready for setting toward the end of this month. With the success of the Eastern Glades, NBW is eager to do their part to update this impressive park for Houston.

Adapting Design

Extensive research went into developing the Master Plan for Memorial Park. Yet all the information needed for a final design may not be available during the design phase. It is after the contract is awarded and underbrush and invasive species are removed that one can really see what assets are available to work with. An openness on the part of the client and the designer are essential to let the design evolve with the receipt of new information. When the client is interested, the designer sees possibilities, and funds are available to expand or evolve scope, amazing things can happen during the construction administration phase of a project. In the Glades, a tree inventory of areas adjacent to the fault line and wetland allowed for such an evolution of design. The original concept of a path at grade through this area shifted to that of a boardwalk—less tied to the ground and more easily able to handle fallen snags or low wet areas. The boardwalk now allows for an immersive experience of the wetland area without undue impact on the ground plane of this unique habitat.

Adaptive, Sustainable Options for Waterwise Utahans Red Butte Garden

“Dramatic curving stone walls … transform the hillside into a sculptural composition of vegetation, masonry, flat planes, and sensual slopes. … Stone colors soften as they ascend the slope, reds and oranges within the lower portions of the Garden; beiges and creams predominate in the upper regions. The lower walls are the most refined and gardenesque. The uppermost walls are the most rustic and naturalistic, echoing the foothills rock formations.”

These beautiful words of designer Tres Fromme (3 Fromme Design) describe the impact of Red Butte Garden’s three-acre Water Conservation Garden. The garden, designed by Studio Outside (Dallas, Texas) and 3 Fromme Design (Sanford, Flordia), recently earned Studio Outside a well-deserved Award of Excellence from the Texas Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects.

The Water Conservation Garden opened to the public in May 2017, but planning for the project began years before. Because Utah is the second driest state in the nation, a major focus of the Water Conservation Garden from the beginning was to provide a living showcase of beautiful and dense plantings while using less water than more traditional gardens. The Water Conservation Garden is arranged around eleven themes and offers a range of gardening aesthetics to entice different tastes. Each theme demonstrates a unique way that waterwise plants, both native and non-native, can be used in landscaping to reduce water use and entice people to conserve water.

From bold sweeps of ground covers to masses of waterwise shrubs, the garden includes an impressive diversity of plants. More than 460 different species were obtained from sources across the Salt Lake valley and western states, or grown at Red Butte Garden. A few endangered plants are featured, including Uinta Basin hookless cactus (Sclerocactus wetlandicus) and Pariette cactus (Sclerocactus brevispinus), and the rare but culturally important Four Corners potato (Solanum jamesii). Coordinating the procurement of plant material was a challenging but necessary task in order to fill one of Red Butte Garden’s largest landscaped gardens.

Education as well as inspiration awaits the visitor. Interpretation throughout the garden describes the many ways that incorporating water-wise and native plants into a landscape design can reduce water use. The signage shows how to design, plant, and irrigate plants according to their respective water requirements (“hydro-zones”) and install efficient irrigation methods and systems to capture and reuse rainfall in the landscape. Additional materials explain how various plant adaptations reduce the loss of water they absorb from the landscape. Where native plants are used, the public is able to learn how those natives support local wildlife, including native bees and pollinators.

In addition to promoting water conservation, the guiding principles of the project addressed a broad range of sustainability practices and goals. These included considerations for the identification and sourcing of plants; reusing site resources, such as topsoil and boulders; and using local, sustainably produced, and recyclable materials. Being water-wise, however, was the central focus. Many methods for achieving that are showcased. In multiple areas, the garden collects and reuses rainwater on-site through a passive rainwater harvesting system. To maximize water-efficient irrigation, 85% of the beds are irrigated with low-volume drip emitters and check valves, and highly efficient sprinkler nozzles replace traditional spray heads in the remaining locations. The overall system also includes “smart” irrigation technology with an on-site weather station and irrigation management software.

Successful completion of the project required continual communication and collaboration between the project design firms, Gramoll Construction, project managers from the University of Utah and Red Butte Garden, and Garden staff, including the Executive Director, Development staff, and Horticulture and irrigation staff. The stunning results are perfectly designed to inspire Utahans to embrace a new, water-wise approach to landscaping.

Water Conservation Garden Themes

- Waterwise Mixed Border — Drought-tolerant and -adapted plants, displayed in a western interpretation of the classic English perennial border, showcase how gardeners can maintain traditional aesthetics with water-wise plantings.

- Adaptive Beauty — Hardy plants, whose appearances or lifecycles (such as summer dormancy) directly relate to their water-conserving physiological adaptations.

- Groundcover Tapestry — Patterns of large-scale, crisp, bold sweeps of groundcover perennials and ornamental grasses run perpendicular and parallel to the slope, with accents of shrubs, small trees, and evergreens.

- Prospect Point Pavilion and Rain Garden — An open-air pavilion serves as a gathering place and landmark, beckoning guests to the upper portions of the Garden with colorful adjacent plantings of shrubs, perennials, ornamental grasses, and bulbs.

- Desert Harvest — A series of five depressed planting beds show how vegetable, herb, and fruit production can be achieved in dry land climates. Woody shrubs and fruit trees requiring larger amounts of water flourish in the lower levels. Plants tolerating drier conditions are found higher up on the basin walls and rims, sharing space with nitrogen fixers and pollinator-friendly plants.

- Gravel Garden — This small section overlooking the entire Water Conservation Garden uses plants 12 inches tall or less, showcasing both ornamental characteristics and extreme resilience.

- Flowering Shrub Hillside — This west-facing slope is planted in masses of waterwise shrubs. It derives inspiration from the patterns of native vegetation on the distant hillsides and the seasonal changes and transformations of the native landscape.

Photos: All photos courtesy of University of Utah.

As Seen on CPC’s Rare Plant Academy

Reintroductions, like other land management activities, require design and planning for successful implementation. The Center for Plant Conservation has distilled guidelines and a framework of questions to walk through as you design a rare plant reintroduction. This invaluable resource can be found as part of the Rare Plant Reintroduction and Translocation section of the CPC Best Practices Guidelines.

CONSERVATION CHAMPION

Todd Bittner

Charged with the stewardship of 3,600 acres of breath-taking beautiful natural areas at Cornell Botanic Gardens, Todd Bittner has the joy and challenge of overseeing a diverse landscape, which includes gorges, bogs, glens, meadows, wildflower preserves, lakes, and old-growth forests. His careful attention to his charges, including federally endangered plants, and his wonderful commitment to engaging students and the public to connect and care for nature are exemplary.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

Growing up on a small Midwestern farm, my connection to plants formed early. But what really sparked my interest was my first experience walking through a restored burr oak savanna in northern Illinois. This once common community type is now among the rarest globally. Learning that we were responsible for their destruction, but could have a role in bringing them back, was transformational for me.

What was your path to becoming a Director of Natural Areas at a botanic garden?

I have had the privilege and benefit to have so many amazing mentors throughout my career. I owe each one a debt that I am working to pay forward to this next passionate generation. Learning from and engaging with plant conservation partnerships and networks throughout my career has been foundational for me personally, allowing me to grow professionally and contribute to the science of plant conservation and ecological restoration. Striving to conserve our collective natural heritage has been a goal that I brought to each stage of my career, whether it was organizing a volunteer effort to restore U.S. Forest Service shale barrens in Southern Illinois as a graduate student or working toward recovery of the Federally threatened prairie bush clover (Lespedeza leptostachya) as a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Recovery Team Member. Working with and for a diversity of conservation organizations, including not-for profits, state or federal agencies, and education-focused institutions, has been tremendously valuable, allowing me to gain perspective through various lenses. My most formative professional engagements were with Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, The Nature Conservancy, the Illinois Plant Society, the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, and presently with Cornell University and its Botanic Gardens.

What about working with plants has surprised you?

Resilience. I am typically hesitant to share this perspective, as I fear some in our society will take this out of context to justify conservation inaction, or worse. Yet I am astounded regularly with the resilience our native flora has had in the face of so many stressors. It gives me hope that our collective conservation and education work, coupled with nature’s resilience, will be a successful recipe for a new paradigm in our relationship with nature.

What is your biggest challenge in managing the natural lands at Cornell Botanic Gardens?

When I talk to and teach Cornell students, I encourage them to not only become subject matter experts for their particular field, but also learn and develop effective communication skills. One may think that, in managing 3,600 acres of natural area holdings across dozens of preserves (including a third of the campus), managing the resource is the primary work. It does take a fair amount of my time, but managing people – and their positive or negative interactions with the environment – is paramount. Accommodating and balancing recreation, academic use, community benefits, volunteer and staff stewardship, neighbor relations, and politics is all about communicating with people effectively, and it constitutes a principle strategy toward conservation.

In your experience, how are horticulture and landscape design connected to natural lands management?

One of the great revolutions underway in our higher education systems is breaking down some of the artificial constructs we previously created for disciplines, degrees, and careers. Today, students are increasingly pursuing interdisciplinary studies. This is a welcome change, as anyone involved in natural land management would benefit from the intimate knowledge gained from horticulture, landscape design, or other related fields. Equally beneficial, I see an increasing cross-pollination of knowledge and practice from natural land management outwards to these sister disciplines, as well as to studies in global development, sustainability, and international conservation agriculture. Cornell Landscape Architecture students, as an example, have used the Gardens’ natural areas as living laboratories for their capstone studio planning and design course. The more we recognize and model our natural systems in our cultivated and built environments, the better it is for nature and for ourselves.

Why do you think it is important for students and the public to engage with natural lands?

Your question reminded me of the quote from Baba Dioum, “In the end we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught.” Nature can be a wonderful mentor in her own right, and often our role initially is simply to invite and foster a connection. As appreciation and curiosity grows, we can then cultivate a deeper understanding of the all the values that nature provides – spanning the intrinsic to the personal. This connection then becomes infectious, but in a good way, as connection evolves into engagement and action.

What current approaches or research in conservation excite you most?

I am keenly interested in how we can adjust our land management practices to concurrently address biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation strategies. In the Northeast, our forest systems are under stress from climate extremes, including increased average and extreme precipitation events, multiple invasive forest pests, and white-tailed deer overpopulation. At the Botanic Gardens, we are experimenting with reshaping how we manage our landscapes to address these challenges at different spatial scales.

At the private landowner scale, we are focusing on habitats and landscaping that benefit pollinators and wildlife, through demonstration sites with accompanying “how-to” planting guides. We also strive to conserve our rarest flora. Here the American globeflower (Trollius laxus) and Leedy’s roseroot (Rhodiola integrifolia ssp. leedyi) have been a focus for seed bank collections, ex situ propagation, and augmentation and introduction projects.

On a regional level, we have been at the cutting edge of testing and assessing novel approaches to managing deer overpopulation in urban, suburban, and rural landscapes.

At the ecosystem level, we have been partnering in the development of various biocontrol agents to address the invasive hemlock woolly adelgid, an aphid-like insect threatening eastern hemlocks (Tsuga canadensis) and associated biodiversity in hemlock-dominated forests.

And at the global level, we are embarking on an initiative we call Future Forests, to augment and replant trees that will be more resilient in a future climate and sequester carbon for years to come.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Employment Opportunities

The Nature Conservancy is a global conservation organization dedicated to conserving the lands and waters on which all life depends. Guided by science, our teams create innovative, on-the-ground solutions to our world’s toughest challenges so that nature and people can thrive together.

The California Chapter is searching for an Island Scientist to work with Conservancy colleagues and partners to conserve the islands of the Californias, including the eight California Channel Islands, and the Pacific Islands of Mexico’s state of Baja California. The Island Scientist will be a member of our Santa Cruz Island Preserve project team and will contribute to our Island Resilience Strategy as well. The Island Scientist will focus on the terrestrial biota of the islands of the Californias, with a concentration on terrestrial vertebrates and invertebrates. The Island Scientist contributes to and leads development of climate-change-adapted conservation planning documents, applied research projects, and implementation of conservation management strategies on Santa Cruz Island and across the islands of the Californias archipelago. The Island Scientist coordinates and advances the Santa Cruz Island Project’s applied research agenda and facilitates field work and logistical support for research, monitoring and conservation management. The Island Scientist independently identifies conservation challenges and applies the scientific approach to help address them. The Island Scientist strategically and effectively communicates –through publication and oral presentation –the science to inform conservation in islands and island habitats in California and to export select, high priority conservation strategies and practices to islands elsewhere.

This video provides an aerial tour of the Preserve.

The preferred location for this position is in Ventura, California.

If you have questions about this position, please contact The Nature Conservancy in California’s Talent Manager, Amber Mello at amber.mello@tnc.org or connect on LinkedIn. See full job posting and apply with CV/resume and cover letter here (careers.nature.org Job # 49144)

Are you an experienced professional with expertise in native plants, their production, and use in habitat restoration? If so, this may be the job for you. The Institute for Applied Ecology is hiring a Program Director for our Plant Materials Program.

Position: Program Director, Plant Materials Program

Office location: Corvallis, Oregon

Status: Regular, full time

Compensation: $26.42-$33.00, depending on experience, plus competitive benefits package (health insurance, 401k, paid time off, etc.).

Closing date: November 27, 2020.

About Us: The Institute for Applied Ecology (IAE) is a dynamic nonprofit organization founded in 1999 whose mission is to conserve native species and habitats through restoration, research and education. We fill a unique niche among nonprofits and work with a diverse group of partners including federal, state and county agencies and municipalities to accomplish our mission. We maintain an open and convivial office environment with approximately 24 regular staff in our main office in Corvallis, OR and branch office in Santa Fe, NM. We are committed to diversity and equity in our work place and the communities we serve. Please see our mission and diversity statements.

Position Summary: IAE is seeking a Program Director with a diverse skill set to manage our Plant Materials Program. This program works in all areas of native plant and seed production, from wildland seed collection to agricultural production, and partnership coordination through outreach to professionals and the public. The Plant Materials Program Director manages IAE’s native plant farm, wild seed collection activities, native seed partnerships in Oregon, and the Native Seed Network website. This position also coordinates the production of the National Native Seed Conference. Our farm facilities are located in Corvallis, Oregon, and include seed production for restoration of habitats (e.g. prairie, coastal grassland), and conservation and recovery of rare plants (e.g., Nelson’s checkermallow and Bradshaw’s lomatium) and wildlife (e.g., Fender’s blue butterfly and streaked horned lark) using a variety of plant materials. IAE works with agencies to collect wild seed for conservation and increase, hiring and coordinating seed collection staff in Oregon and elsewhere. This program serves a coordination role for the Willamette Valley Native Plant Partnership and the Coastal Native Seed Partnership in Oregon, and manages the Native Seed Network including its website (www.nativeseednetwork.org) and national conference. This Program Director supervises up to five staff.

Department: Horticulture

Supervisor: Director of Horticulture

Supervises: Volunteers, Gardeners, Conservation or Horticulture Intern(s)

FLSA Salary Classification: Full-Time

Availability: Ability to work a flexible schedule, occasional extended work hours, including evenings, weekends and holidays.

General Summary: Coordinate the propagation of plants for conservation, collections, fundraisers and education programs to align with Huntsville Botanical Garden mission, conservation and sustainability initiatives. Manage operations, staff and volunteers involved with propagation, conservation growing in greenhouse and nursery area.

How to Apply: To apply to any open position, download and complete the Employment Application. Then submit your completed Employment Application, cover letter, and resume as follows:

Download and complete the Employment Application

E-mail: hr@hsvbg.org

*Please include the position in which you are applying for in the subject line of your email.

Or Mail:

Huntsville Botanical Garden

4747 Bob Wallace Ave.

Huntsville, AL 35805

All applications submitted need to indicate the name of the position for which you are applying as well as your recent salary history and requirements.

Ways to Help CPC

Support CPC by Using AmazonSmile

As many of us are now working from home and relying on home delivery more and more, we wanted to remind you that you can keep your home stocked AND SavePlants. If you plan to shop online, please consider using AmazonSmile.

AmazonSmile offers all of the same items, prices, and benefits of its sister website, Amazon.com, but with one distinct difference. When you shop on AmazonSmile, the AmazonSmile Foundation contributes 0.05 percent of eligible purchases to the charity of your choice. (Center for Plant Conservation).

There is no cost to charities or customers, and 100 percent of the donation generated from eligible purchases goes to the charity of your choice.

AmazonSmile is very simple to use—all you need is an Amazon account. On your first visit to the AmazonSmile site, you will be asked to log in to your Amazon account with existing username and password (you do not need a separate account for AmazonSmile). You will then be prompted to choose a charity to support. During future visits to the site, AmazonSmile will remember your charity and apply eligible purchases towards your total contribution—it is that easy!

If you do not have an Amazon account, you can create one on AmazonSmile.

Once you have selected Center for Plant Conservation as your charity, you are ready to start shopping. However, you must be logged into smile.amazon.com—donations will not be applied to purchases made on the Amazon.com main site or mobile app. It is also important to remember that not everything qualifies for AmazonSmile contributions.

So, stay safe inside, and when ordering online, remember you can still help save plants. Please feel free to share this email with your friends and family and ask them to select Center for Plant Conservation.

Thank you all for ALL you do.

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today