Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

May 2022 Newsletter

In this May issue of Save Plants, we explore the importance of plant parentage. I suspect that most of us don’t think much about “Who’s your daddy?” in the plant world, however, research shows that appropriate mating does play an important role in the persistence of rare plants. One of the consequences of small population size is the loss of suitable mates. Knowing this problem, our CPC Participating Institutions are working to use the same sorts of breeding stud book techniques that are used by zoos to ensure healthy rare plants are produced in our gardens. This may involve human-assisted pollination or specific horticultural techniques to ensure healthy reproduction. Yet plants have evolved their own tricks to encourage good seed production, too. Learn about the tricks the Texas Poppy-mallow uses to ensure the best mating possible and how clever Australian cycads use heat and chemicals to attract specific thrip pollinators to specific cycad cones. These are just more examples of the very intricate and amazing wonders of plants!

We hope you are enjoying this beautiful spring with plentiful bees and birds,

Joyce Maschinski

CPC President & CEOConservation Horticulture and Parental Controls

Based on an interview with Mike DeMotta

Over 200 types of rare plants in Hawai’i are thought to have fewer than 50 individuals remaining in the wild. For many of these plants, ex situ conservation may be key to both learning more about the plants and growing more to spark their revival — or at the very least, to prevent their extinction. The National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) is one of the institutions in Hawai’i that helps these and the many other rare plants of the state. Yet maintaining such rare species in their gardens and nurseries, when only a limited number of wild plants can contribute to their genetic pool, presents unique challenges and decision making for the horticulturalists who care for the plants.

Bringing a species into the garden may offer a chance to boost breeding in that species. In Hawai’i, many species have lost their pollinators and become fragmented, remaining in only small, isolated populations. The federally endangered ‘awiwi (Kadua cookiana) is one such species, currently having only two populations. The ‘awiwi is also suffering from low production of strong pollen. By taking cuttings (genetic clones) of the wild plants and hand pollinating the mature plants, NTBG horticulturalists are able to generate more seed than can be collected in the wild. This process allows them to control both mother and father plants and mix the two populations, resulting in seed for both long-term conservation and additional conservation efforts. Another federally endangered plant, the culturally important uhiuhi (Mezoneuron kavaiensis), struggles from low recruitment in the wild but has found some breeding successes on NTBG grounds. The garden is a great place to grow uhiuhi and develop plant material to enhance wild populations as there is nothing for the plants to hybridize with!

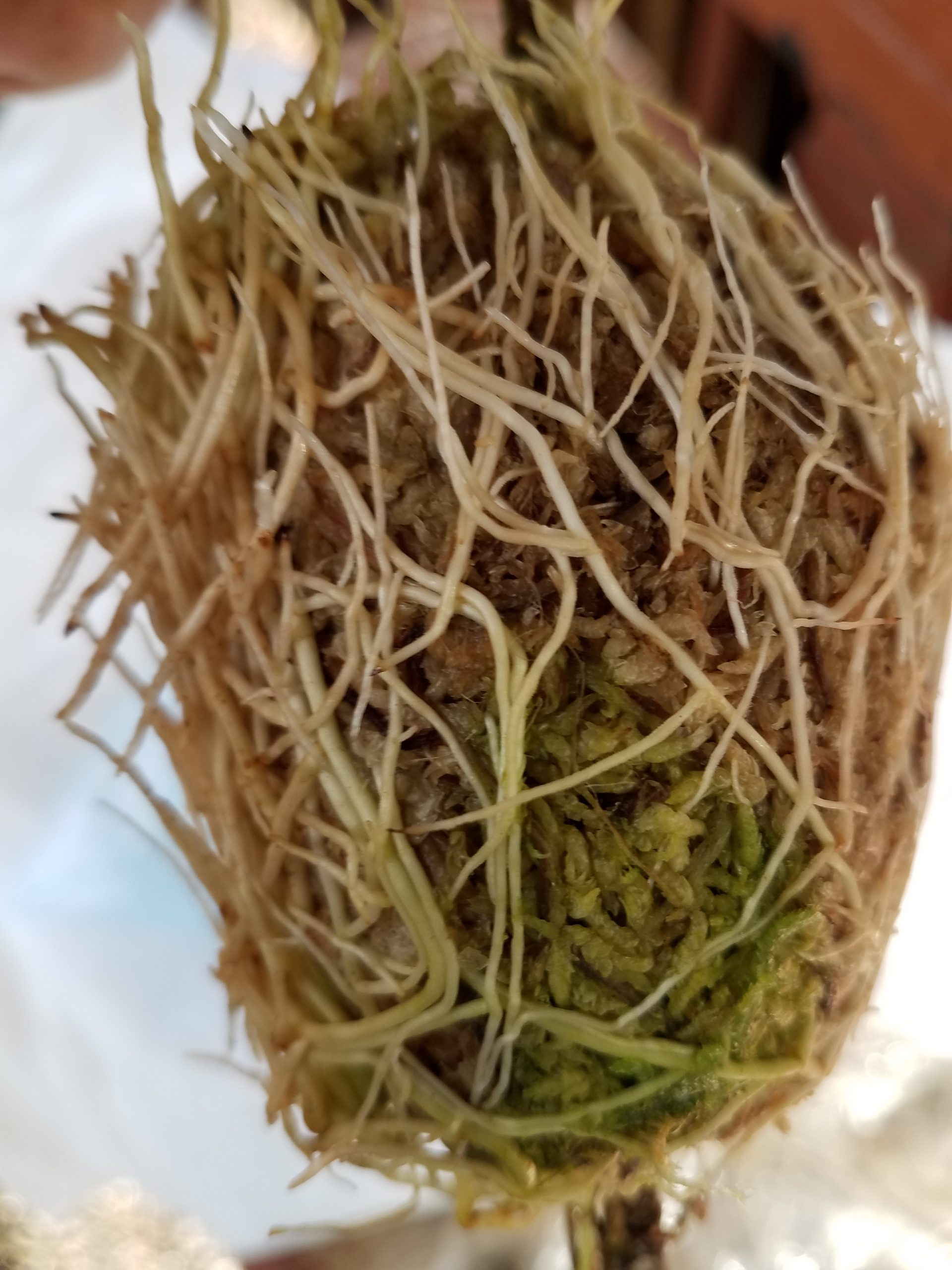

The experienced horticulturalists at NTBG are increasingly using their expertise to bring species into conservation collections. Air layering is a method of propagating new trees or shrubs from stems still attached to the parent plant. The stem is treated and wrapped in moist medium in a manner that promotes root growth from the stem, then eventually the newly rooted branch can be cut from the parent plant as a new clone. After demonstrating air layering on a specimen already held in an NTBG garden, their team received approval from the Hawaiian Department of Forestry and Wildlife to use this method to create a conservation collection of māhoe (Alectryon macroccus var. macrococcus). Air layering has proven to be quite useful in securing māhoe, as it has been difficult to obtain seed from the plant – the seeds have a tasty component which once fed humans and now attracts rats, and bagging the fruits to secure them is rarely an option due to twig borer infestations weakening the many small supporting branches. By hiking or helicoptering out to the few sites with māhoe on Kaua’i to set air layers, NTBG botanists don’t need to guess the timing of seed ripening or try to beat the herbivores – they can simply return in 3-4 months when roots have established and take their newly propagated plants with them.

Once at the garden, the air-layered clones of their wild parents are used to produce seed for long-term conservation and research. Unlike seeds collected from wild plants, the horticulturalists can hand pollinate to control the identities of both mother and father plants. With numbers of wild plants declining from around 500 to under 300 in the last 25 years, it is critical to capture as much genetic diversity from the wild populations as possible — and this horticultural technique has been the perfect tool to do so.

When horticulturalists breed plants — especially rare plants — record keeping is key. To better track parentage of plants at the garden, NTBG has made some changes to its living collections database. The placement of the parent information for the first generation of cultivated plants (known as F1 plants) is moved to a more prominent place in the database, and hot links help the horticulturalists track down the information they need to make decisions about the next generation of plants or evaluate their restoration potential. Not only are maternal plants recorded, but the pollen donor (paternal plant) is also noted when an individual is hand-pollinated. Such record-keeping will help the team maintain diversity through many generations.

At NTBG, horticultural techniques and the tools to record breeding efforts are part of their conservation tool box and demonstrate the importance of conservation horticulture for rare plants. With so many Hawaiian plants under threat of extinction —and hundreds already at critically low population numbers — conservation horticulture will continue to play a key role to help these wonderfully unique species survive. Yet survival is insufficient. The horticulture staff works with the hopes that the threats to Hawai’i’s flora can be reversed, allowing the plants to return to their important roles in the natural ecosystem.

-

Once widespread on the leeward side of the all Hawaiian islands, mahoe (Alectryon macrococcus var. macrococcus) has only a few hundred individuals remaining in the wild. Besides loss of habitat and competition from invasive plants, the species lacks recruitment as rodents are drawn to its seed and it is plagued by the black twig borer. -

The horticultural technique of air layering, promotes the growth of roots from a treatment on a branch that does not make contact with the soil. Instead, soil or moss is wrapped around the treated area. Here, a nana (Gardenia remyi) was successfully propagated from an air layer generating lots of roots. photo by Mike DeMotta, NTBG. -

The difficult terrain of many of the natural areas supporting rare plants prompts the use of helicopters to aid conservation work. Helicopter dropoff and hours of hiking were required to reach some of the remaining populations of mahoe (Alectryon macrococcus var. macrococcus). The difficulty of getting to seed in a timely manner (before rodents!) and inability to bag flowers makes airlayering a great option for brining this species into a conservation collection. photo by Mike DeMotta.

Are We Related? Delving into Genetics to Build a Palm Breeding Program

In the southern peninsula of Haiti, just over one dozen carossier palms (Attalea crassipatha), one of the rarest palms in the Americas, remain in the wild. All the trees are mature, and there appears to be no natural recruitment of new seedlings. Fortunately, in the 1990s botanists collected seeds from carossier palms and sent them to botanical institutions. This act may help the rare palm persevere into the future — but only if all the remaining plants can be managed as one population, no matter where they are found. Montgomery Botanical Center (MBC) and Chicago Botanic Garden (CBG) are pulling together the information that will help the botanical institutions holding ex situ collections and conservationists in Haiti to do just that.

Historically, management of the species was largely passive – trees were left to reproduce with other individuals at each institution without oversight or intervention. Most seeds produced and shared as a result of the breeding between just a few individuals. Now MBC and CBG are adapting zoo studbook management software (PMx) to manage exceptional plant species like this rare palm. Initial efforts include developing a PMxceptional program and working with several species to determine the best way to integrate the program in conservation management for plants. MBC executive director, Patrick Griffith, Ph.D., points out that carrosier palms are not only a perfect candidate for its use, but that they provide a great model to guide the management of other species.

As a first step, the program needs information on the relatedness of all individuals to be bred and managed. Zoe Diaz-Martin, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at CBG, has generated genomic data on the remaining carossier palms. In addition to the wild palms, 60 palms spread across five botanical institutions remain from seed sent to them in the 1990s and 14 individuals comprising a captive-born generation were included in the study. Using next-generation sequencing to genotype the palms, Zoe delved into the levels of genetic diversity found in the wild population, the founders, and the first generation of captive-born individuals. Identifying levels of diversity and inbreeding will help guide management of the palms to keep the captive population genetically robust, and ideally enable the development of optimal plant material for reintroduction.

While still refining the relatedness table needed for the PMxceptional software program, Zoe has found some interesting results. First, a subset of the captive-born plants appear to be extreme genetic outliers. They could not be matched to father plants and may be hybrids — or even a different species included in the study as a result of mislabeling. Overall, the captive-born population shows significantly lower genetic diversity and significantly more inbreeding than either their founder parents or the wild population. Both of these results highlight the need for the software as well as a more active hand in managing carossier palms.

The team also wanted to know the extent to which the founders of the garden population were representative of the wild population. Many of the garden trees could not be matched to wild mothers or fathers or both. This means that the native populations may yet harbor some diversity not represented in gardens; therefore additional collections from Haiti could bolster the ex situ collections. And, although the parents of these unmatched founders appear to have been extinguished, their progeny in the collections can contribute more genetic diversity to the wild. Botanists in Hawai’i have been creative and innovative in their use of drones for conservation work, and it is conceivable that drones could be used to pollinate the wild palms in Haiti with pollen from captive founders or their offspring. A reintroduction may also benefit from selecting plants with founders of unknown parentage. These approaches would truly involve managing all of the carrosier palms as one population, ideally using the PMxceptional program as the guide.

Enacting the guidelines from the breeding program will require extensive coordination. The gardens have already begun this cooperation, working together to get the project started and sharing genetic samples and collection data. Most of the gardens are located in Miami – MBC, Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden, the Tropical Resource and Education Center at University of Florida, and Chapman Field (USDA ARS Subtropical Horticultural Research Station). The Singapore Botanic Gardens is also on board, as well as conservationists in Haiti – particularly William Cinea at the Cayes Botanical Garden (Jardin Botanique des Cayes).

The carrosier palm project and plant studbook work highlight how a collaborative framework can advance conservation. Conservation through collaboration offers both hope and practical pathways for this critically endangered palm, as well as many other endangered species, to flourish in the future.

The Wonderful World of OZ Cycads

Cycads, one of the most endangered plant groups on earth, belong to an ancient lineage of tropical and semi-tropical gymnosperms with male and female plants. More than half of all cycad species are threatened or endangered. Conservation efforts for some of the endangered species are underway on most continents where cycads are native, yet little effort has focused on their pollinators. Most species have very specific pollinators — and in many cases, only one species of pollinator. This makes it essential for long term viability to conserve not only each species of cycad, but also its host-specific pollinators. Unfortunately, the pollinators for many cycad species are still unknown.

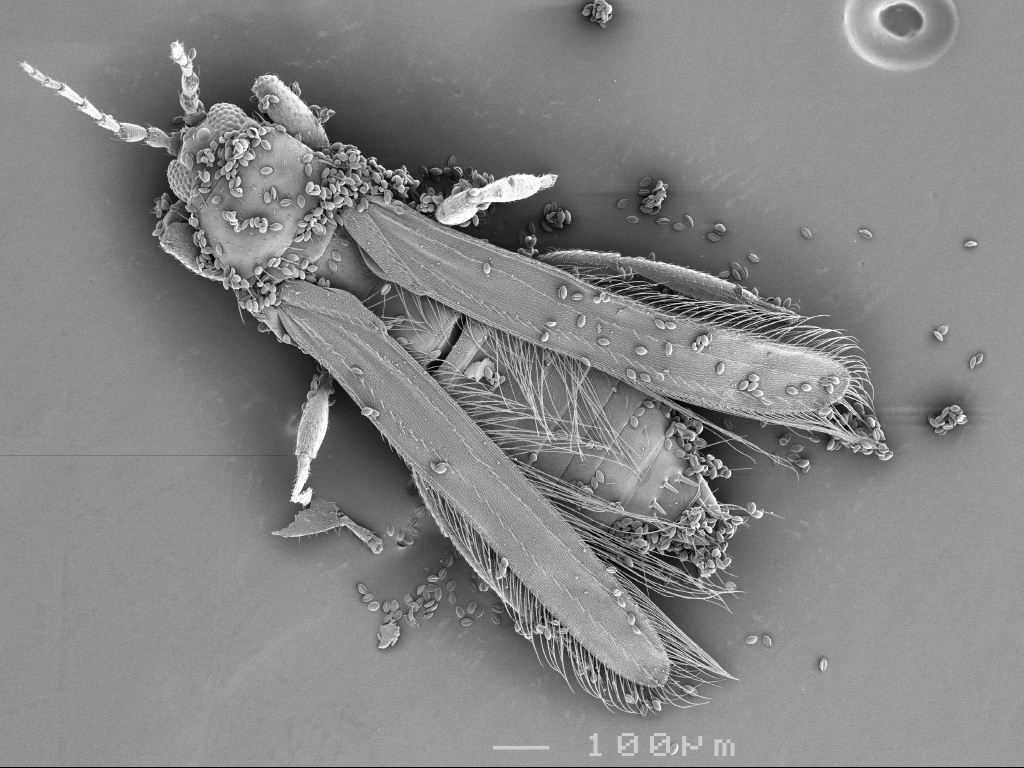

Australia (‘OZ’) is well known for its many iconic and fascinating animals. But the continent is also home to some very unusual plants and the mutualistic animals that interact with them, including endemic cycads and their specific pollinators. OZ has a high diversity of cycads, with four of the 10 cycad genera (Cycas, Bowenia, Macrozamia and Lepidozamia) and more than 60 of the ~ 300 described species. Most cycad pollinators are beetles, but one exception is found in Australia. Thrips in the genus Cycadothrips (Order Thysanoptera) — tiny insects not much larger than a pencil point — are the specific pollinator of many species of Macrozamia, a genus endemic to Australia.

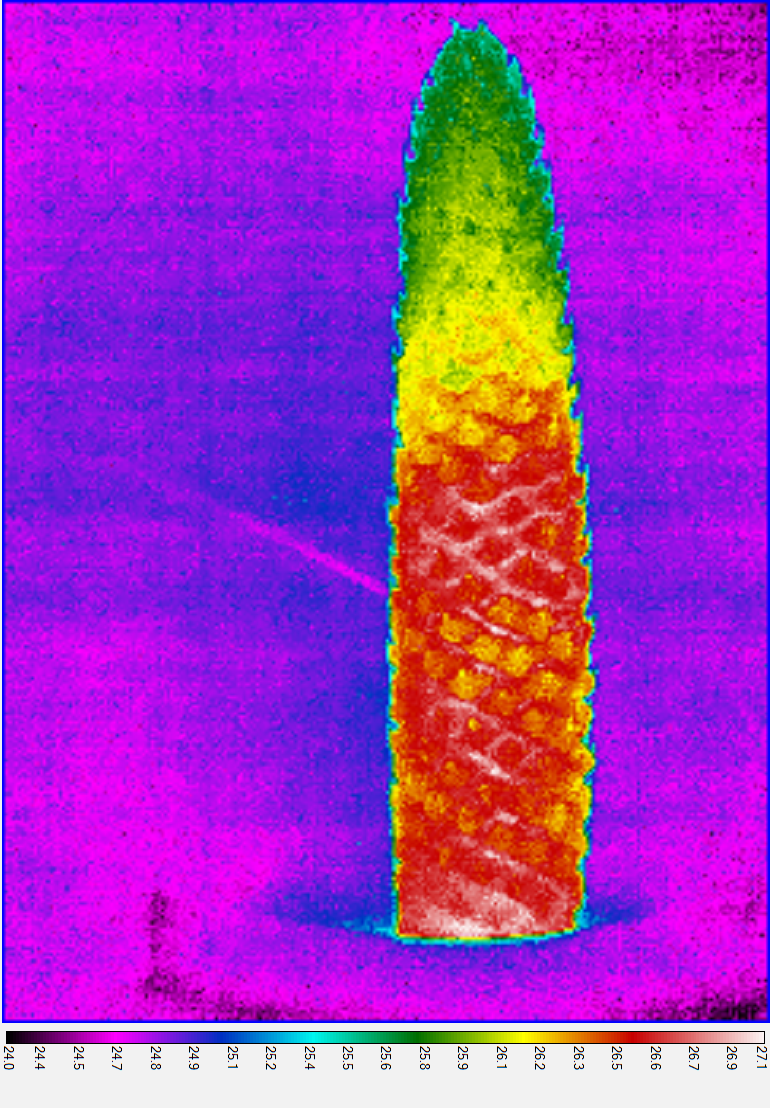

Macrozamia pollination is a story of mimicry and deceit. Male cones release pollen and female cones become receptive over a period of a week to ten days for each cone. Throughout this time, both male and female cones release strong chemical odors and become thermogenic for a few hours each day — heating up to 25°F (~15°C) above the ambient temperature. The heat expels and scent attracts Cycadothrips — but the thrips thrive only on the male cone, where they feed on pollen, breed, and depart, covered with pollen. Returning later in the day, some thrips fly to female cones, where they pollinate but do not breed. In essence, the female cone tricks the tiny pollinators to bring pollen inside by mimicking the male cone’s chemical volatiles. The deluded thrips fly out of the female cone the next day to continue the dance.

The story gets even more complicated, based on molecular biology and chemistry. In eastern Australia, Cycadothrips chadwicki is the named species of pollinator for these Macrozamia species. Although the Cycadothrips all look alike from region to region in the east, molecular genetic studies show that they actually segregate into many different ‘cryptic species’ that are markedly different. Each one is found in a different geographic region from north to south. Furthermore, the chemical lure emitted by cones of Macrozamia varies from region to region, and each cryptic Cycadothrips species appears to be attracted only to specific cone chemicals produced by the Macrozamia within its own region.

What does this have to do with conservation of cycads and their pollinator? Cycads cannot reproduce without their host-specific pollinator. The pollinator cannot survive without the food and breeding sites provided by male cones. Pollination cannot occur if thrips are not induced to move out temporarily from the comfort of their host cone, and the involvement of thermogenesis and specific cone chemistry is a vital part of the process of expulsion and attraction. Before the molecular studies of the thrips pollinator and the accompanying pollination research, conservation planners only considered having to manage each of the eastern Macrozamia species along with a single thrips pollinator, regardless of the thrips’ home region. Now efforts are needed to better understand how to protect and manage each of the cryptic Cycadothrips species along with its particular host plant. And this type of diversification of cycads and their pollinators appears to occur in other parts of the world, further emphasizing the critical need to fully understand the pollination systems of these iconic plants.

References:

1. Donaldson, J. 2003. Cycads status survey and conservation action plan. International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland.

2. Fragnière, Y., S. Bétrisey, L. Cardinaux, M. Stoffel, G. Kozlowski. 2015. Fighting their last stand? A global analysis of the distribution and conservation status of gymnosperms. Journal of Biogeography 42: 809-820. Doi: 10.1111/jbi.12480.

3. Brookes, D. R., Hereward, J. P., Terry, L. I., Walter, G. H., 2015. Evolutionary dynamics of a cycad obligate pollination mutualism – Pattern and process in extant Macrozamia cycads and their specialist thrips pollinators. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 93: 83-93. DOI:.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2015.07.003.

4. Terry, I., C. Moore, R. Roemer, and G. Walter. 2021. Unique chemistry associated with diversification in a tightly coupled cycad-thrips obligate pollination mutualism. Phytochemistry 186: article 112715: 1-19. doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2021.112715.

Lauren Weisenberger

This month’s conservation champion, Dr. Lauren Weisenberger is an exemplary spokesperson for rare plant conservation. Working with the critically endangered Schiedea kaalae, she learned first-hand about the challenges of seed germination and reintroduction. In 2016, Dr. Weisenberger received the David Given Award for Excellence in Plant Conservation. Her professional accomplishments are many including her service on the Hawaiian Plant Specialist Group of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and the Advisory Council for Laukahi: The Hawai’i Plant Conservation Network. She co-authored the Hawaiʻi Strategy for Plant Conservation and recently coordinated the Hawai’i Rare Plant Genetics Workshop, where among many topics discussed was the important concern of hybridization. Lauren’s unyielding support and collaborations across many stakeholders is truly an essential formula for Saving Plants. We are so grateful for you, Lauren!

When did you first fall in love with plants?

When I was a kid in Pennsylvania. I loved hiking around the forest with my grandfather in the Pocono Mountains and along the Pocono Creek, as well as picking blueberries and walnuts. Looking back, I guess those were my first fruit collections!

What was your career path to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service?

I began my career in plant conservation in Hawaiʻi at the Lyon Arboretum Seed Conservation Laboratory as a student hire, learning about seed germination and storage behavior of plants native to Hawaiʻi from Alvin Yoshinaga. That position grew into a fulltime job. We eventually started another seed bank for the Army Natural Resources Program on Oʻahu, where we were able to imbed the seed banking operations into the rare plant management to support reintroduction and restoration efforts for many endangered plant species.

When I left the program after 14 years with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, I wanted to utilize what we had to learned to support more plant conservation efforts, and to have the opportunity to learn from and work with more conservation practitioners.

Also, in 2012, prior to joining USFWS, I was fortunate to work with a colleague on a project for the National Tropical Botanical Garden, Lyon Arboretum, and the State of Hawaiʻi, to determine whether a plant conservation network in Hawaiʻi would be beneficial. The Hawaiʻi Strategy for Plant Conservation was then drafted, building off the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation, and Laukahi, the Hawaiʻi Plant Conservation Network, was established in 2014. These experiences helped me to understand how critical collaboration and communication are for conservation. In 2016, I started my current position as Plant Recovery Coordinator at the Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office, working on recovery efforts for 442 threatened and endangered plant taxa in Hawaiʻi and the Mariana Islands — almost half of all the listed plants.

In your experience, what are some of the pressing conservation needs related to Hawaiʻi’s rare and native plants?

In Hawaiʻi, I think invasive species are the primary drivers of extinction. Invasive species directly consume, damage, or outcompete native plants, and they indirectly degrade and destroy native habitats. We need better tools to control a large suite of invasive species, especially plants, invertebrates, and diseases. We also need more support to implement large-scale controls for wide-spread invasive species, such as the rodents and feral ungulates that prevent the establishment of resilient habitats and populations of plants where they are present. We need to prevent further decline of habitats in order to have healthy watersheds and biodiverse, functioning ecosystems.

I think another need is to strengthen the connection between people and plants. It is so hard to access a lot of natural places, and the hikes can be challenging. Many people do not see native plants regularly, and it is hard to form a personal connection to them. I think that communicating the value and role that plants and people have for each other can benefit not only conservation efforts, but also the well-being and connection people have to plants and native habitats, especially those near where they live.

What new research or methodologies show promise in advancing the conservation needs of Hawaii’s rare and native plants?

We have made a lot of progress with ex situ tools and research, including seed storage, tissue culture, and cryopreservation. When the Lyon Arboretum seed bank started, there was not a lot known about long-term germplasm storage for plants native to Hawaiʻi. Now, thanks to amazing collaborations, including the formation of the Hawaiʻi Seed Bank Partnership, we have an idea about how well most species will store in seed banks, and we are working on tissue culture and cryopreservation protocols for the species that cannot store conventionally in seed banks long-term (i.e., exceptional species). This research has allowed us to secure species in ex situ collections, and buy us time to do the in situ habitat restoration. However, we need more technology, research, and resources to maintain healthy ecosystems for in situ habitats to prevent further population declines and reintroduce new populations and augment existing populations from the ex situ collections.

What are some of your current projects at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service? What successes or challenges have you encountered in your work?

This year we are working on several Recovery plans for over 100 listed plants, and an additional similar number of plants are going through their five-year status review. Currently, I am working on support and resources for the University of Hawaiʻi’s Plant Extinction Prevention Program (PEPP), which focuses on preventing extinction and recovery efforts for ~250 taxa endemic to Hawaiʻi that have 50 or fewer individuals remaining, and the State of Hawaiʻi Rare Plant Program, which works with PEPP and also supports a number of rare plant nurseries and ex situ facilities throughout Hawaiʻi.

I recently was part of an organizing committee comprised of partners from academic institutions and botanical gardens. We just completed facilitating a 10-part workshop series on how genetic and genomic techniques can be applied to rare plant management, using species examples from PEPP. We were excited to bring together groups of people from 80 different organizations — including students and faculty, conservation practitioners, landowners, government agencies, and non-governmental organizations — that might not have met or partnered before, but were eager to work together and learn from each other how to best utilize their research to help prevent extinctions and support the recovery of rare plants.

Many of the examples of questions or problems that PEPP presented are now being studied by the researchers who attended! And I cannot thank Dr. Joyce Maschinski enough for her participation and presentation during the workshop series, all of which provided perspective from examples across the country and applicable guidance for our preventing extinction goals.

What has surprised you about working with and learning more about rare plants?

There is so much to learn! When I first started working at the Lyon Arboretum Seed Conservation Lab, we could not get over how a single daily task, such as looking at germination assays, could lead to breakthroughs that are critical for species survival and recovery. It was astonishing to see how squeezing the seed of this species, or noting the color variation in the seeds of another species, could be the difference between knowing whether or not you have a backup germplasm collection of an individual. With the help of partners such as CPC, these useful observations eventually grew into protocols and best management practices that we hope build confidence and reliability in our seed banking collections.

I would not say that I am surprised, but I am incredibly humbled and grateful for all the amazing people tirelessly working on rare plants. Their perseverance and optimism provide the most creative ideas, collaborations, and results. The skills, expertise, and motivation of the plant conservation community, in the face of extinctions and lack of resources, are so inspiring and bring so much potential to all the future work to come.

What advice do you have for newcomers to the field of plant conservation?

There is so much to learn and observe and discover, that can really help save plants. So look, observe, study — but most importantly, ask questions and communicate. Don’t be afraid to reach out to someone, to ask questions, to speak up. Collaborate and share every chance you have, because that is how you make an impact.

What advice would you give to the public who want to learn more about how they can help save imperiled plant species?

There are many ways to help, no matter your interests or skills. From outreach and education supplies and curriculum to technology to field logistics, if there is a way to make any part of rare plant management a little more effective or a little cheaper, it can go very far. We have so many questions about the ecology of all these species, what they need to persist and thrive, and how to protect them. You do not have to be a botanist to get involved.

National Collection Spotlight: Texas Poppy-mallow

The federally endangered Texas Poppy-mallow (Callirhoe scabriuscula) is a perennial herb with stunning wine-purple, cup-shaped flowers that bloom from May to June. The flowers serve as a key source of nectar, pollen, and shelter for local bees, which help the Texas Poppy-mallow reproduce by spreading pollen between plants. This process includes a fascinating daily ritual performed by the flower petals. Each flower opens in the morning a few hours after sunrise and closes right before sunset. If a flower is lucky enough to be pollinated by a visiting bee, however, it will close 30 to 90 minutes later and never open again, as it focuses its energy on producing seed. If a flower is not pollinated, it continues its daily opening and closing ritual for six to eight days before wilting, unpollinated.

In the wild, the Texas Poppy-mallow is limited to a loose, deep sand habitat in the Rolling Plains vegetation zone of Texas. Much of this habitat has been lost in recent years to sand mining, agriculture, improved pastures, residential and business development, and oil and gas development. Due to its beautiful flowers, this species is also susceptible to flower picking, which harms the wild population. The San Antonio Botanical Garden, a CPC Participating Institution, has collected seed from this species and propagated it in their greenhouse, yet transplanting these plants into test plots has proven to be difficult. Plant conservationists will continue working to address these challenges to ensure the Texas Poppy-mallow survives well into the future.

We invite you to learn more about the Texas Poppy-mallow on its National Collection Plant Profile and support its conservation with a Plant Sponsorship.

As Seen on CPC’s Rare Plant Academy: All in the Family: The Case for Collecting by Maternal Lines

Having a connection to your mother is important to a plant–well, at least to a plant record. In a video prepared specifically for the Rare Plant Academy, Heather Schneider of Santa Barbara Botanic Garden makes the case for collecting seeds along maternal lines–that is, keeping seed from different mother plants separate. Collecting along maternal lines provides depth to a collection. The general rule is that 50 maternal lines captured evenly through a population can capture the vast majority of the genetic diversity within that population. Processing and storing seeds along maternal lines ensures that each line can be represented in restoration and reintroduction efforts, and also provides the opportunity to ask more questions when conducting research on a species.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Employment Opportunities

The Executive Director, U.S. Botanic Garden (USBG) maintains the USBG as a nationally recognized scientific and educational institution and living plant museum. The Executive Director has oversight for all major functions, including administration, education, outreach, science, conservation, horticulture, facilities maintenance and capital renewal. The USBG is an independent federal agency administered by the Architect of the Capitol, a legislative branch agency in Washington, D.C.

Please share as you’d like and for more information and to apply: https://www.usajobs.gov/GetJob/ViewDetails/652301000

Applications due: May 31, 2022

Eligibility: Applications are accepted from all U.S. citizens.

Major Duties:

Oversees all administrative operations including strategic planning, personnel management, budget formulation and execution, asset management and safety.

Exercises executive responsibility for the operation, maintenance and renovation of the physical facilities, including recommendations for short-term and long-term capital improvements. Leads master planning efforts to establish future directions and position the USBG as a model sustainable facility.

Directs and oversees all communication activities for the USBG, including with the media, external leaders in public gardens, botany and plant science and Congress. Sets and oversees the strategic direction for public outreach, educational programming and exhibits. Ensures the USBG reaches diverse adult and youth audiences locally and nationally through a range of formats and through in-person and online tours and programming, both on and off-campus.

Serves as a technical expert in botany, horticulture and plant conservation. Presents papers and lectures as a professional expert in the fields of botany, horticulture and public garden administration to national and international professional societies and organizations.

Develops and oversees implementation of policies and guidelines for plant collections. Provides for plant rescue, in conjunction with the Animal Plant, Health Inspection Service (APHIS) of the USDA, for plants traded in violation of international trade agreements for endangered species.

Ensures the care, health and curation of a documented and diverse plant collection that serve the USBG’s educational and conservation mission. Engages with the horticulture community to develop plant collections, test new varieties and support plant conservation through collection and in-situ preservation of threatened and endangered plants.

Advances institutional priorities of conservation, sustainability and plant science through national and international partnerships, outreach activities and in-house internships, training opportunities and research. Makes the USBG facilities and collections available to the scientific community and advances the USBG-led plant science and conservation work.

Interacts with AOC staff, senior staff, officials from other agencies and public. Demonstrates skill in developing and delivering oral and written presentations as well as making recommendations on management issues in concise and convincing language.

Builds coalitions internally and with other organizations and stakeholders to achieve common goals. Consulted by congressional members, staffs and constituents on policies and programs regarding relevant professional problems, issues and practices. Represents the USBG to local, national and international professional groups and societies and other government agencies.

Provides an inclusive and equitable workplace that fosters the development of others, facilitates cooperation and teamwork and supports constructive resolution of conflicts.

Complies with all safety and health practices, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations and ensures employees wear required protective equipment.

The Morton Arboretum is a world-renowned nonprofit public garden dedicated to the planting and conservation of trees for a greener, healthier, and more beautiful world. The Arboretum founded ArbNet — the global, interactive network of arboreta and tree-focused professionals — in 2011. ArbNet facilitates the sharing of knowledge, experience, and other resources to help arboreta meet their institutional goals and works to raise professional standards through the ArbNet Arboretum Accreditation Program. ArbNet is an award winning initiative that has grown considerably in its programmatic scope and global reach. We seek a highly motivated, innovative professional to lead ArbNet into its second decade. This person will oversee the entire ArbNet program, from staff supervision to strategic planning and the creation and implementation of new programs and initiatives. This is an incredible opportunity for an emerging leader in the public garden community to influence and advance the cause of arboreta globally. This is a senior role based at The Morton Arboretum, with the opportunity to work closely with the Arboretum’s leadership team as well as directors and program leaders from arboreta around the world.

Position Summary: Manage, grow, and promote ArbNet—the global interactive network of arboreta—founded and led by The Morton Arboretum. ArbNet programs include the Morton Register of Arboreta, The ArbNet Arboretum Accreditation Program, the BGCI/ArbNet Partnership Programme, and other ArbNet projects and initiatives that advance the goals and professionalism of the global arboretum community. Manage all aspects of ArbNet including strategic planning, programming, arboretum network support and growth, and budget management. Lead efforts to continually improve how ArbNet operates, the information and services it provides, and how best to reach its key audiences and stakeholders.

Essential Functions:

- Responsible for overseeing the daily management of ArbNet, including supervising staff, ensuring programs are operating at the highest standard, building and maintaining relationships with new arboreta and tree-focused networks, developing new resources and programming opportunities, and improving ArbNet processes and procedures for efficiency and effectiveness.

- Lead and implement strategic planning for the growth of ArbNet, exploring new opportunities to support and build the global arboretum community.

- Work closely with The Morton Arboretum’s Global Tree Conservation Program and Chicago Region Trees Initiative to advance two strategic priority areas for ArbNet: 1) tree conservation and establishing/supporting arboreta in global biodiversity hotspots and 2) arboretum-led urban and community forestry.

- Work in concert with other Arboretum staff members within the realm of the Science and Conservation, Collections, Learning and Engagement, and other program areas to ensure unity of goals and strategies that advance both ArbNet and The Morton Arboretum’s strategic plan.

- Ensure up-to-date, relevant resources and information to support the growth and learning of the global arboretum community.

- Generate sustainable growth of ArbNet through innovative ways to create revenue through ArbNet services and programming, secure grant funding and corporate sponsorship, and pursue other opportunities as appropriate.

- Build the global community of arboreta through organizing and attending networking events, conferences, site visits, and training workshops. Represent ArbNet at national and international conferences, meetings, and through various media channels.

- Supervise the ArbNet Coordinator. Supervisory duties include scheduling and job assignments, performance feedback, recognition, and staff development and training, as well as recruitment and selection as needed, in keeping with the Arboretum’s policies and procedures.

- Other duties as required.

Qualifications: Bachelor’s degree in plant sciences, horticulture, environmental science, environmental education, or related field required. 5+ years of related work experience required, or a combination of a higher degree or related certification plus relevant work experience. Demonstrated experience with and knowledge of public gardens and arboreta required. Supervisory experience, as well as experience leading diverse teams of people, required. Program or project management experience required. Excellent written and verbal communication skills required. Fluency in language(s) other than English beneficial.

Success Factors: Ability to maintain a professional, courteous, and enthusiastic presence with both internal and external audiences. Ability to maintain many meaningful, inclusive relationships with a diversity of stakeholders, and to understand the needs and values of many collaborators. Innovative thinker, with an ability to horizon scan for new opportunities to advance program goals. Actively seeks out opportunities for collaboration with other staff and external partners, including liaising with senior leadership at arboreta around the world. Confident and engaging public speaker and communicator. Proficiency with Microsoft Office and Google applications beneficial. Ability to learn and evaluate new technology and digital tools when appropriate. Ability to weigh decisions, establish priorities, and set goals for self and team members. Ability to embrace and align with the organization’s employee core values to be inclusive, take ownership, work together, keep learning, and make the Arboretum exceptional.

Physical Demands and Work Environment: The physical demands and work environment characteristics described here are representative of those that must be met by an employee to successfully perform the essential functions of this job. Reasonable accommodations may be made to enable individuals with disabilities to perform these essential functions.

- Physical Demands: May require some physical activity: walking over uneven terrain, bending, limited lifting and carrying. Requires some local, national, and potentially international travel.

- Work Environment: Work is performed primarily indoors. This position is designated as a hybrid-eligible position, allowing for some work to be performed off premise, during regular hours of work.

- Equipment: General office equipment.

To apply, visit: https://mortonarb.org/join-support/employment/

For full consideration, please include resume and cover letter with application.

All Arboretum employees will be required to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 and provide proof of that status in order to maintain their employment.

The Morton Arboretum is a champion of diversity, supporting a culture of inclusion that attracts, inspires, and engages people to achieve success. The Arboretum is committed to hire and develop employees based on job-related qualifications irrespective of race, religion, color, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, age, disability, or veteran status. To increase diversity in professions related to the public garden realm, we encourage applications from underrepresented minorities, persons with disabilities, and veterans.

The Morton Arboretum is dedicated to complying with our obligations as an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer. All applicants are guaranteed equal consideration for employment.

Ways to Help CPC

Support CPC By Using AmazonSmile

As many of us are now working from home and relying on home delivery more and more, we want to remind you that you can keep your home stocked AND Save Plants. If you plan to shop online, please consider using AmazonSmile.

AmazonSmile offers all of the same items, prices, and benefits of its sister website, Amazon.com, but with one distinct difference. When you shop on AmazonSmile, the AmazonSmile Foundation contributes 0.05 percent of eligible purchases to the charity of your choice. (Center for Plant Conservation).

There is no cost to charities or customers, and 100 percent of the donation generated from eligible purchases goes to the charity of your choice.

AmazonSmile is very simple to use—all you need is an Amazon account. On your first visit to the AmazonSmile site, you will be asked to log in to your Amazon account with existing username and password (you do not need a separate account for AmazonSmile). You will then be prompted to choose a charity to support. During future visits to the site, AmazonSmile will remember your charity and apply eligible purchases towards your total contribution—it is that easy!

If you do not have an Amazon account, you can create one on AmazonSmile.

Once you have selected Center for Plant Conservation as your charity, you are ready to start shopping. However, you must be logged into smile.amazon.com—donations will not be applied to purchases made on the Amazon.com main site or mobile app. It is also important to remember that not everything qualifies for AmazonSmile contributions.

So, stay safe inside, and when ordering online, remember you can still help save plants. Please feel free to share this email with your friends and family and ask them to select Center for Plant Conservation.

Thank you all for ALL you do.

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today