Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

March 2021 Newsletter

In this month’s Save Plants, we explore the nature of rarity and give examples of our participating institutions’ efforts to conserve plants that exhibit different types of rarity. Species may have few individuals, few populations, and very few areas where conditions are appropriate for their growth. The extremely rare Showy stick seed exemplifies this kind of rarity. Alternatively, a species may be rare because its specific habitats, such as the bogs of the Green Pitcher plant, face threats wherever the species occurs. Pathogens pose particularly serious threats even to species once considered common and abundant, like the Hawaiian Ohi’a lehua. At CPC, we care about all of these rare plant species and the people like our Conservation Champion, Anna Strong, working to save them for future generations.

Joyce Maschinski

CPC President & CEOWhat Makes a Plant Rare?

The Center for Plant Conservation works to save plants –specifically rare plants. In 1981, Deborah Rabinowitz described seven forms of rarity –each depending on geographical distribution, habitat specificity, and/or local population size.

A plant can be broadly distributed over a wide range, but still be rare because it occurs only in specialized habitats and has small populations, as with climbing vine fern (Microgramma heterophylla). Very narrow range-endemics are also often very rare, such as the cliff palace milkvetch (Astragalus deterior) found only on the south rim of Mesa Verde in the white zone of the upper cliff house sandstone formations. Still others may have populations of large numbers, such as San Diego thornmint (Acanthomintha ilicifolia) with a few population searching tens of thousands in good years, but is restricted to specific habitats in small area –in the thornmint’s case clay soils in coastal San Diego county.

The reason why a plant is rare relates to its biogeographical history and the threats it has faced. Historically, some species were once broadly distributed, but are now restricted to small fragments due to habitat destruction. Other species are naturally rare, meaning they never had a broad distribution, never had large numbers of individuals. They are vulnerable to habitat destruction and climate change, especially if they have highly specific habitat requirements. They may be more susceptible to unpredictable events, such as landslides and fires, which cause catastrophic loss. NatureServe, a CPC network partner, gathers information on plants throughout their range to evaluate their rarity and the degree of threat they face. They have developed a consistent method for evaluating the imperilment of a species, ranging from critically imperiled to demonstrably secure.

The roles rare plants play within their ecosystems –past, present, and future –is rarely understood, largely because it is unexamined. CPC partners are learning more about these plants as they work to save them. We do know that each has a unique story and we hope you enjoy reading some of them here and in exploring plants in CPC’s National Collection.

A Carnivorous Ambassador

A rare treat greets scout troops guided by Carrie Radcliffe on lands managed by the Nature Conservancy (TNC) in Georgia: endangered green pitcher plants (Sarracenia oreophila) in their natural, boggy habitats. Faces of scouts and adults light up as they experience the reality of carnivorous plants and the special places in which they live. Although the species’ range stretches over several states, such encounters are rare. Green pitcher plants reside in isolated and scattered see page bog habitats. These bogs, already few in number, are declining further in the face of agricultural development, changes in disturbance regimes (such as fire), changes in hydrology, and other threats. Fortunately, Atlanta Botanical Garden (the Garden), where Carrie works, has a bog display in its Conservation Garden where visitors can experience the wonder of these carnivorous plants.

The green pitcher plant is a charismatic ambassador for the plight of endangered plants. Pitcher plants have a unique shape that begs a closer look, rewarding admirers with insight into how these botanic predators trap insects for nutrients. At the Garden, the education department collects pitcher plant material for children to explore in classes, and the plants are often on display at a fundraising events. Carrie describes the reactions of children and adults as a “spark of wonder as these plants’ mysteries unravel before their eyes.” The staff use the charisma of pitcher plants to promote both an appreciation for plants and an awareness of their needs. The green pitcher plant provides a superb example of a conservation success, showing how imperiled plants can be helped when their needs are addressed. Carrie’s hope is that this story will continue to inspire the public, especially future conservation biologists and stewards of nature.

-

Green pitcher plant. Photo by: Carrie Radcliffe -

Green pitcher plant (Sarracenia oreophila) in its bog habitat during recovery plan monitoring with the Bog Learning Network in Georgia in the spring of 2018. Photo by: Carrie Radcliffe -

The green pitcher plant gains new colors as the year progresses, here sporting orange and yellow during floral monitoring for maternal line seed collections. Photo by: Emily Coffey

The green pitcher plant has drawn many to its cause. Population sites in Georgia and North Carolina are conserved by TNC and have been actively managed for a long time. Management efforts continue to improve as researchers working with conservationists in the Southern Appalachia Bog Learning Network (BLN) increase the understanding of the bog hydrology and plant needs. The Georgia Plant Conservation Alliance (GPCA) has helped lead monitoring, management, and plant enhancements for green pitcher plants in Georgia. They have also served as a mentor for the Alabama PCA as it began to reverse the decline of the their Populations where we have supplied plants and helped with work days included public and private lands. The work of these collaborative groups benefits multiple pitcher plant species (Sarracenia oreophila, S. jonesii, and S. purpureavar. montana), as well as many other plant and animal species endemic to boggy habitats in the mountains, such as swamp pink and bog turtle.

Within this web of conservationists, the Garden plays a few key roles, both leading and supporting. Their primary work continues to be conservation horticulture and seed banking. When called upon, the team will also hop over to Alabama to help with a work event and monitor populations. They maintain indexed conservation collections –living plants with origin and parentage tracked. In 2006, a population augmentation using living collections was conducted at a microsite adjacent to the main Georgia population. Seed collections are being made to include the species in CPC’s upcoming IMLS longevity study and to maintain collection diversity by maternal lines. The Garden’s efforts to capture the diversity of the North Carolina and Georgia populations through seed banking will soon extend to Alabama. And use of material supplied by the Garden for reintroductions at new sites within the natural range of the species remains a hopeful possibility.

In the meantime, the Garden continues to monitor the 2006 augmentation and promote the plight and progress of green pitcher plant to the public. According to Carrie, the species may never reach the goal of having 18 stable populations on protected lands, as is currently required for delisting. Yet great advances have already been made through the work of the Garden, The Nature Conservancy, the PCAs, the BLN, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and future benefits for this species will grow out of further collaboration across its range. Conservationists working with green pitcher plant have great hopes that it will continue to be a model for success and an ambassador for developing partnerships, including the Southeastern Plant Conservation Alliance, as well as other plants in need of collaborative efforts.

The Lone Population on a Slippery Slope

As Wendy Gibble, Program Manager for the Rare Plant Care and Conservation Program (Rare Care) at University of Washington Botanic Gardens, spends hours upon hours staring into a microscope, gently scraping the seed coat off the root radicle of showy stickseed seeds, she has plenty of time to contemplate how the need for this meticulous step might relate to a species adaption. Showy stickseed (Hackelia venusta), like many other Hackelia species, inhabits steep slopes with loose, well-drained substrates and low competing vegetation. Wendy can imagine the seeds tumbling down a steep slope, scraping between sand and rocks, not germinating until the soil environment is just right. This is just one of the ecological principles that she enjoys contemplating while growing increasingly familiar with this special, endangered plant.

Though showy stickseed may be adapted to the loose-soiled and steep environment of Washington’s Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest, the location of the species’ only known population in the Cascades, its human helpers are definitely not. The Rare Care team and their partners find the terrain highly challenging for conducting monitoring and out planting efforts, in terms of safety and limiting impact on the site. The soils are shallow, well-drained sand with low organic matter content and high rock and gravel content. This habitat was historically maintained by frequent wildfires that kept the understory vegetation, particularly shrub cover, sparse. With today’s emphasis on wildfire control, however, human efforts are often needed to reduce tree and shrub cover. Although the U.S. Forest Service has been able to remove some trees when snow is present, other vegetation controls would be too disruptive to the soil. Even otherwise low-impact monitoring activities need to be limited to prevent soil disturbances that might bury or damage plants. To develop a safe and statistically robust method to track changes in population, Rare Care is currently working on a monitoring plan that uses photo points, point counts and other no-impact techniques.

Showy stickseed’s limited range and habitat specificity complicate recovery efforts, by reducing options for establishing new populations to build redundancy. The sole existing population includes just 300 individuals. This makes it exceedingly vulnerable to catastrophic loss from an unpredictable event, such as a landslide. Wendy’s team and others working with the species are currently searching for reintroduction sites to develop three stable self-sustaining populations, the goal of this endangered species’ recovery plan. Each site needs to support an average of 1,000 individuals. Finding suitable sites to introduce new populations has been difficult, however, and as yet none have been found.

Despite the challenges, the Rare Care team is working steadily towards showy stickseed’s recovery. An early step was learning how to grow the species, which proved quite difficult. Prior to 2004, only limited success with seed germination was achieved, and micropropagation techniques were instead used to create 30 clones placed in an introduction site. Techniques for seed germination were subsequently developed by Jeanie Taylor, a graduate student of Dr. Sarah Reichard, and refined by Rare Care, providing today’s preferred method for propagation. The seeds require cold stratification and embryo excision (hence Wendy’s hours under a microscope) for successful germination. With propagation methods now established, the team’s recent focus has been on augmenting the existing populations and attempting an introduction at a new site.

As an aid for locating suitable sites, Rare Care completed a physical and vegetation characterization of showy stickseed’s habitat to inform habitat modeling efforts. The team is currently working with University of Washington Professor Monika Moskal and her graduate student Drew Foster to complete a habitat characterization model this spring and evaluate the use of drones to identify potential areas with suitable habitat. While the site search is in progress, the U.S. Forest Service will develop a habitat management plan, working with Rare Care and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to set the endangered species on a path towards recovery.

Why is so much effort is being put into one small species? Assigning a measurable value to a single species, especially one that seems to live right on the edge of survival, can be difficult. Yet so much is unknown about the plant’s role in the broader ecosystem. What insects or other life forms does this species support? What are its potential effects on evolutionary change? We do know that the habitat in which showy stickseed occurs is unique and may harbor other unique taxa. Whether or not this species was abundant at one time is unclear, as surveys for additional populations occurred long after fire suppression had fundamentally altered its dry conifer forest habitat. Will this be a high-elevation species that blinks into and out of existence over the long arc of evolution? Or will adaptation lead to species survival in the hotter, drier conditions of future climate scenarios?

Regardless of success over geologic time, showy stickseed offers a noteworthy lesson in species radiation and adaptation. One thing is certain: humans have impacted and changed its environment. Loss of biodiversity, both for this species and others it touches ecologically and evolutionarily, is a consequential outcome of our activities. And so Wendy, and many plant conservationists like her, follow an imperative call to do all that can be done to preserve this one population on the edge.

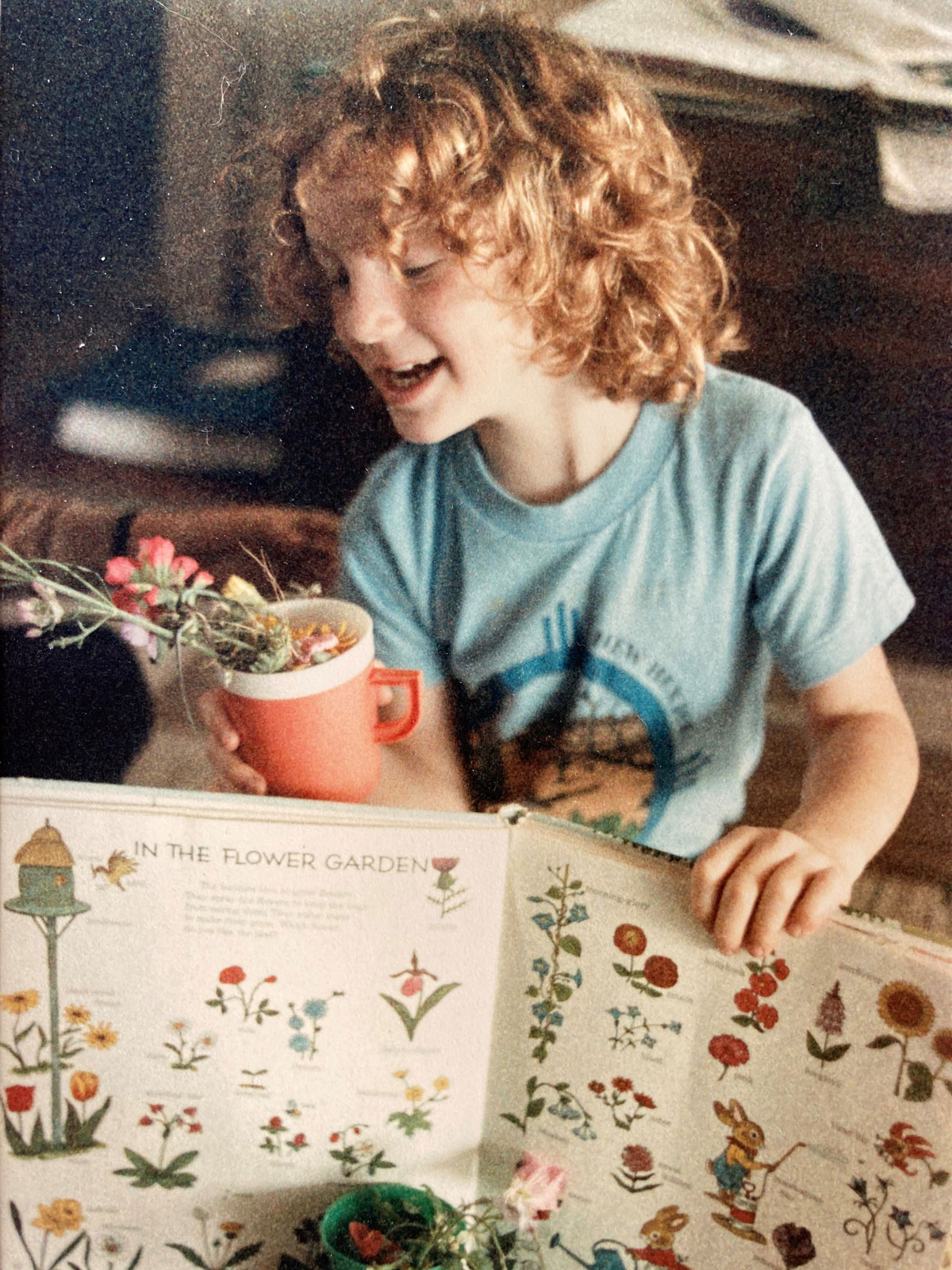

Anna Strong

Working for a state Natural Heritage Program gives a person good perspective about rarity in a state. Our March Conservation Champion has the challenge of working in the very big state of Texas tracking the conservation status of over 400 rare plant species. As a former CPC National Office staff member, Anna knows the importance of tracking rare plant species and is among those dedicated to making good conservation work happen. Texas and all of us say, “Thanks, Anna!”

When did you first fall in love with plants?

Although I did not know it would become a theme in my life, I was introduced to rare plants at a very young age. My dad has a Master’s in Botany and was one of the three initial employees of the now long-defunct Rare Plant Studies Center led by Dr. Marshall Johnston at the University of Texas at Austin. Before I was born in the 70s, they were scouting for and relocating rare plant populations and, to a limited extent, propagating rare plants.Dad was no longer working for the Center by the time I was born, but his interest in plants was very influential to both my brother and me from an early age. We went on family hikes, had plant ID lessons, camped, visited national parks, and learned about native plant gardening. By the time I was a senior in high school, I knew my major in college would be Botany.

What was your path to becoming a botanist with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department?

I was not actually keen on working on rare plants whenI was first introduced to the idea. I wanted to work on pollination biology in graduate school when I applied to Texas State University. Dr. Paula Williamson, who would become my major advisor, had applied for a Section 6 grant (a federal grant from the U.S.Fish and Wildlife Service, administered by the states to support endangered species) to study the federally endangered star cactus (Astrophytum asterias). My first thoughts were on how limiting it would be to work with a rare organism.How would I find enough plants to have a study/thesis? But I was offered a research assistantship and the university was only 30 minutes from home, so I took the challenge. After grad school, I worked for 5 years at CPC as its Conservation Projects Coordinator while it was still based in St. Louis. I then applied and received funding in 2012 for another Section 6 grant to create status assessments of a dozen Texas plants that had been petitioned for listing. I worked at the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) to write the assessments and to have access to their files and expertise. This allowed me to slip into my predecessor’s position when they retired in 2015.

What are the biggest influences on rare plants in Texas?

You may have heard that Texas is a big state. And because of its size and location, it houses a wide variety of ecosystems and geological settings. Texas has mountains, deserts, forests, coastline, scrubland, and short-, mid-and tall-grass prairies. It spans four plant hardiness zones. Annual rainfall ranges from 16” arid West Texas to 60” humid subtropical East Texas. All of this variation has created the opportunity for many rare plants to evolve and persist. But Texas is also a state of great growth. The entire eastern portion, starting from Laredo in the south and Fort Worth in the north, continues to be a rapidly growing area, with Texas projected to have the highest population increase of any U.S. state for the second decade in a row. Roads and water are needed for all these inhabitants. Texas also houses healthy agricultural and oil/gas/wind industries. All of these directly compete for the same soil as Texas’ rare plants.

What are the greatest challenges you face in your work?

You may have heard that Texas is a big state. TPWD has two botanists, a species-focused botanist (that’s me) and a rare plant community ecologist. In addition to many other things, I am responsible for our list of Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN),with over 400 plants. We also have an SGCN list of over 200 rare plant communities. Maintaining these lists is a big chore for two people in addition to our other tasks. It feels overwhelming most days

What about working with plants has surprised you?

There is so much we don’t know! And there is so much I don’t remember!

What new or upcoming research, process, or policy relating to the understanding and conservation of rare plants excites you?

My broader program, the Wildlife Diversity program, was able to hire 1½ temporary data analysts to tackle the immense backlog of plant data we have housed in paper and electronic files at the Texas Natural Diversity Database. These two new employees will be able to focus on the backlog, starting with two federally and state-listed plants in East Texas. This is not a sexy project, but we only have three full-time data specialists for seven taxa biologists and a whole state’s worth of rare plant, plant community, and animal data. To be able to zero in on plant data entry makes accessing and interpreting rare plant data easier for both our external data users and me!

As Seen on Rare Plant Academy

‘Ohi’a lehua’s (Metrosideros polymorpha) large populations, and its status as the most common native tree in Hawaii, may stretch some people’s concept of rare (although anything endemic to Hawaii has limited distribution). Yet a species does not have to be rare to be at risk. ‘Ohi’a lehua and other ‘ohi’a species (Metrosideros sp.) face a dire threat–a fungal infection causing rapid ‘ohi’a death (ROD) that can quickly wipeout large forest stands. At the 2018 National Meeting, Seana Walsh of National Tropical Botanic Garden shared the ambitious plan to conserve these ecologically and culturally important trees. Learn more about the project by watching her engaging video and exploring related information on the Rare Plant Academy platform.

Registration Now Open!

We are delighted to invite you to the 2021 Center for Plant Conservation National Meeting. For the safety of our network, the CPC National Meeting will be held virtually again in 2021. This year’s meeting will focus on reconnecting with our network and sharing plant conservation successes from the past two years, those achievements we have made despite considerable adversity. As we see the light at the end of the COVID-19 tunnel, now is the time to build plans toward a collaborative future in plant conservation research.

Presentation sessions will include updates from the CPC National Office on network wide initiatives and lightning talks from CPC network partners on plant conservation research, accomplishments, and challenges. Working sessions will engage the network. We wish to gather network input for CPC policy paper on the threat of climate change to rare plants. We will ask the network to beta-test our IMLS-funded plant conservation education platform, CPC Rare Plant Academy. Back by popular demand, we will hold our second annual National Meeting Photo Contest, and we will introduce a new communication tool contest. We are looking forward to seeing you there!

Registration closes to CPC PI presenters April 9th, 2021 & to all participants April 30th, 2021.

This year, CPC’s Board of Trustees meeting will take place the Friday following the CPC National Meeting on May 14th, 2021.

LEARN MORE & REGISTER

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Employment Opportunities

POSITION TITLE: Conservation Safeguarding Nursery Horticultural Coordinator

DEPARTMENT: Conservation & Research

REPORTS TO: Conservation Horticulture Manager

FLSA: Exempt

POSITION DESCRIPTION: This position reports to the Conservation Horticulture Manager. The successful candidate will be responsible for curating the ex situ conservation collections of rare and endangered plants, and ensuring the nursery’s physical structures and systems operate efficiently and effectively. This position is based full-time in Gainesville, GA but requires bi-weekly trips to the Atlanta Botanical Garden’s Midtown Atlanta location, and some travel to field sites.

Please email resume, cover letter, and list of three references to Careers at careers@atlantabg.org, all files should include applicants last name, document title, and title of the position you are applying for (Smith_Resume_ConsNursCoord). Review of Applications will begin immediately with interviews starting March 29, 2021.

https://atlantabg.org/employment/conservation-safeguarding-nursery-coordinator/

Lucinda McDade Receives Liberty Hyde Bailey Award

Wonderful News – The American Horticultural Society announced its 2021 Great American Gardener awards yesterday and our very own Lucinda McDade is the recipient of the Liberty Hyde Bailey Award.

The American Horticultural Society’s highest award, the Liberty Hyde Bailey Award is given to an individual who has made significant lifetime contributions to at least three of the following horticultural fields: teaching, research, communications, plant exploration, administration, art, business, and leadership.

North Carolina Botanical Garden Wins Garden Stewardship Award

Given to a public garden that embraces and exemplifies sustainable horticultural practices in design, maintenance, and/or programs. New for 2021.

For more than 50 years, the North Carolina Botanical Garden, a part of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has been engaged in native plant conservation and education. It has worked diligently to cultivate an international reputation as a garden that weaves a conservation ethic through all its programs. Each year, the garden welcomes more than 100,000 visitors. As the region’s most comprehensive knowledge center on native plants, the garden manages over 1,138 acres of land containing 4,500 accessions and 2,500 species. It supports university classes through field trips, community engagement, research facilities, long-term ecological research, and ecosystem monitoring sites. The garden oversees the conservation and management of approximately 1,200 acres of natural areas and conducts research on ecological restoration and germplasm storage. It is a founding member of the national Center for Plant Conservation and holds genetic resources of 80 imperiled southeastern plants for use in restoration and as a safeguard against extinction in the wild.

“Driven By Nature” | Peter Raven Autobiography

DRIVEN BY NATURE

A Personal Journey from Shanghai

to Botany and Global Sustainability

PETER H. RAVEN

FOREWORD BY E.O. WILSON

EDITED BY ERIC ENGLES

US Publication Date: April 15, 2021 Cloth: $35.00 / ISBN: 9780226350554

It’s safe to say that few people have lived lives as thoroughly devoted to plants as Peter H. Raven has.

The longtime director—now president emeritus—of the Missouri Botanical Garden, author of

numerous leading textbooks and several hundred scholarly articles, Raven has been a tireless

champion of sustainability and biodiversity, earning him the plaudit “Hero for the Planet” from Time.

Please contact Tyler McGaughey at tmcgaughey@uchicago.edu for more information.

Published by the Missouri Botanical Garden Press and distributed by the University of Chicago Press

2021 Florida Rare Plant Task Force Meeting

Bok Tower Gardens, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, the Endangered Plant Advisory Council of DOACS/DPI, and the Florida Plant Conservation Alliance are pleased to announce the 2021 Florida Rare Plant Task Force meeting! This year, the meeting will be held virtually during the week of Monday, April 26th – Sunday, May 2nd.

The 2021 Florida Rare Plant Task Force will feature a live introduction and live keynote on April 26th. Pre-recorded presentations on a variety of rare plant topics, and virtual tours will be available throughout the week via links on the meeting page; you will be provided a link to this page upon registration. The Florida Plant Conservation Alliance will lead a discussion or information gathering session for select species in order to inform their listing status and provide updated information to federal and state agencies. The Center for Plant Conservation (CPC) will be providing information about the Florida seed collection initiative, and a myriad of talks from the CPC Rare Plant Academy will be available.

Registration will be free this year, but is required in order to access the meeting content. Registration will be through Bok Tower Gardens’ website, and will open in mid-March. Please look for an email with registration information and a list of speakers in upcoming weeks!

The annual Florida Rare Plant Task Force is a state-wide meeting that brings together the network of conservation professionals from a variety of disciplines and agencies to share approaches and findings, forge new partnerships and discuss rare plant conservation priorities. This annual meeting is made possible by grants from the State of Florida, Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry.

The Mission of the Florida Plant Conservation Alliance (FPCA) is to study and preserve Florida’s flora through multi-disciplinary research, education, and advocacy; facilitate the recovery of rare, threatened, and endangered plants of Florida and the southeastern US through collaborative efforts in our state; and communicate the importance of preserving biodiversity worldwide.

Plant Conservation Alliance, 2021

Native plants are the true green infrastructure we rely upon for healthy, biodiverse ecosystems. They protect us against natural disasters; create wildlife, rare species, and pollinator habitat; and are vital for carbon sequestration. Without native plants, especially their seeds, we do not have the ability to restore functional ecosystems after natural disasters and mitigate the effects of climate change. Investing now in coordinated, research-driven native seed production is an efficient and cost-effective risk management strategy.

Link to preliminary fact sheet: https://www.blm.gov/sites/blm.gov/files/docs/2021-02/NSS%20Progress%202020%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf

Introducing Sonoma Botanical Garden!

Exciting news from Northern California. CPC Board of Trustee member Scot Medbury, executive director for the Quarryhill Botanical Garden, has announced that on March 17th the garden officially became the Sonoma Botanical Garden. Further, the garden has refined its mission and will be focussing on both Asian and Californian plants in the future.

Learn More

Ways to Help CPC

Support CPC By Using AmazonSmile

As many of us are now working from home and relying on home delivery more and more, we want to remind you that you can keep your home stocked AND SavePlants. If you plan to shop online, please consider using AmazonSmile.

AmazonSmile offers all of the same items, prices, and benefits of its sister website, Amazon.com, but with one distinct difference. When you shop on AmazonSmile, the AmazonSmile Foundation contributes 0.05 percent of eligible purchases to the charity of your choice. (Center for Plant Conservation).

There is no cost to charities or customers, and 100 percent of the donation generated from eligible purchases goes to the charity of your choice.

AmazonSmile is very simple to use—all you need is an Amazon account. On your first visit to the AmazonSmile site, you will be asked to log in to your Amazon account with existing username and password (you do not need a separate account for AmazonSmile). You will then be prompted to choose a charity to support. During future visits to the site, AmazonSmile will remember your charity and apply eligible purchases towards your total contribution—it is that easy!

If you do not have an Amazon account, you can create one on AmazonSmile.

Once you have selected Center for Plant Conservation as your charity, you are ready to start shopping. However, you must be logged into smile.amazon.com—donations will not be applied to purchases made on the Amazon.com main site or mobile app. It is also important to remember that not everything qualifies for AmazonSmile contributions.

So, stay safe inside, and when ordering online, remember you can still help save plants. Please feel free to share this email with your friends and family and ask them to select Center for Plant Conservation.

Thank you all for ALL you do.

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today