Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

April 2022 Newsletter

Plants are the foundation of life on our planet and underlie human well-being. They provide our oxygen, food, fuel, and shelter. They clean our air and water, and they moderate our climate. Yet despite these critical functions, many people do not understand why we should conserve plants and why rare plants matter. In this issue of Save Plants, we explore the notion that plants give us a sense of place and how they serve as indicators of healthy ecosystems. Bringing back healthy ecosystem function brings back rare and common species, which collectively provide a suite of services that we need. Our Participating Institution, the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, describes their efforts to connect people to desert plants and the animals and people that use them. Our colleagues at the Mattole Restoration Council describe their work to restore healthy ecosystem function. We hear from our Conservation Champion, James Kwon, who describes the native Hawaiians’ indigenous knowledge, practices, and proverbs—ʻōlelo noeʻau. These collective stories beautifully illustrate why plants matter.

Wishing you a beautiful spring,

Joyce Maschinski

CPC President & CEOBuilding a Sense of Place

Visitors to Tucson—and many residents—come from various locales that are often wetter and greener. Some may feel a bit intimidated by the prickly plants, the unusual animals, and the desert they inhabit. Even long-term residents may not be acquainted with the long history and rich natural heritage of their corner of the Sonoran Desert. Fortunately, the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum helps both residents and visitors feel comfortable approaching the desert to take a closer look at its wonders. A central goal of the Museum is to help residents build a sense of place and to inspire all to live in harmony with nature.

Displays at the Museum are designed to encourage this connection, placing animals side-by-side with the plants that they depend on. Visitors can connect the presence of pollinators in the air and lizards underfoot to the plants growing among them. This visible plant-animal connection is enough to entice some people into taking native plants home to add to their own landscaping. Botany Curator, Erik Rakestraw, likes to point out how the Museum’s plant sales provide benefits to wildlife. “It is a tangible way for them to kind of partake in conservation themselves,” he states. “They can actually see the changes they make at home firsthand by adding a few plants … they can see these changes take place: the birds, bees, and lizards coming back.” Some gardeners return year after year, discussing their plant additions and observations with the nursery staff and demonstrating their joy in the plants. Native plant additions to local landscapes also serve to boost pollinator corridors throughout Tucson and keep these important ecosystem service providers thriving.

The Museum’s native plant sales are a great opportunity for people already interested in mitigating their footprint on the environment. But others may need help to move beyond a desire to recreate the green and flowery landscaping in which they grew up. The Museum shows visitors that the desert has its own beauty to offer. Its displays concentrate unique, intriguing plants and expose people to a large variety of species found in the desert. A common refrain around the Museum—“What is this plant?”—presents an opportunity to share information about the plants and the roles they play in desert ecosystems.

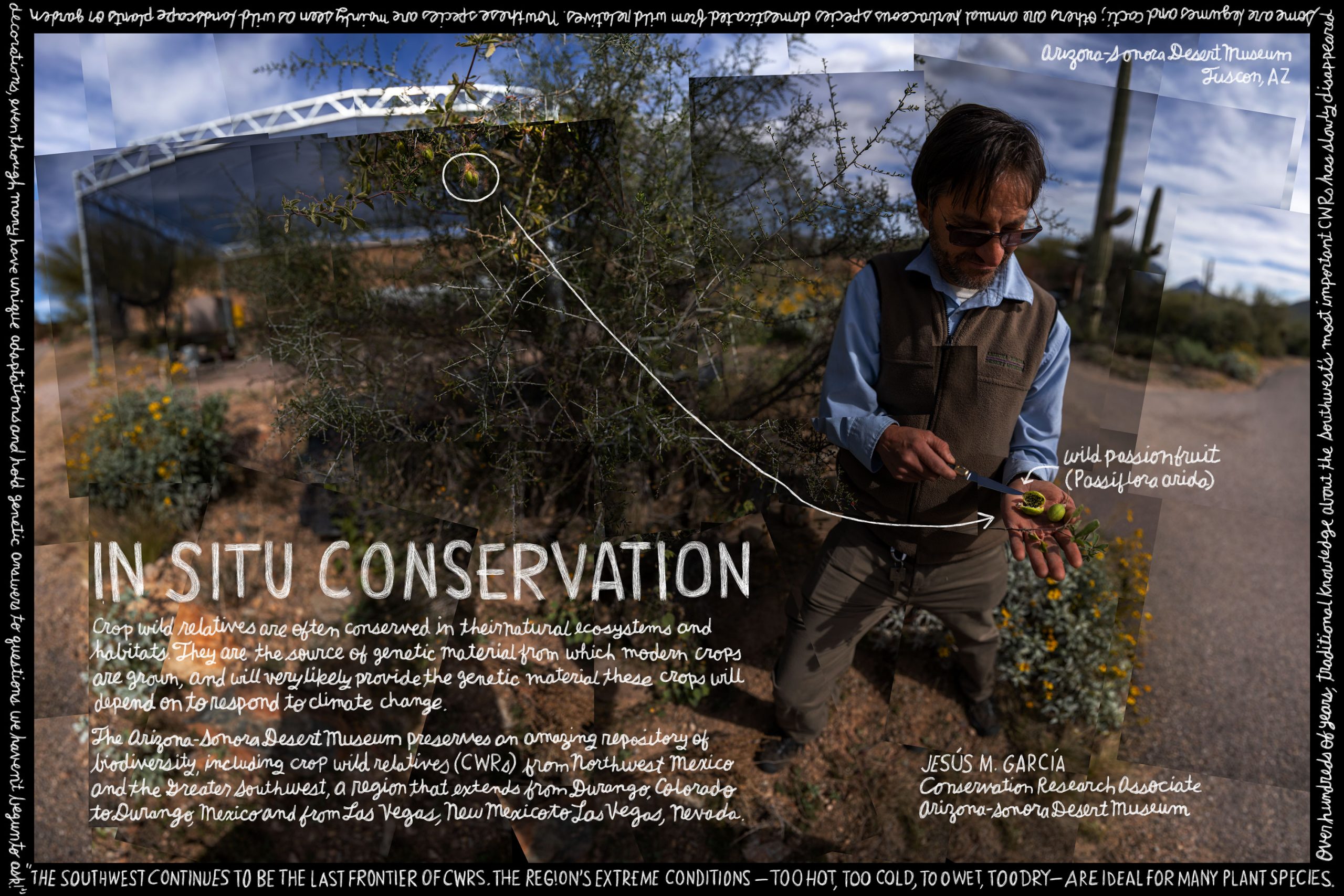

Another hook that builds interest in native plants is … their tastiness! Spicy chiltepín (Capsicum annum) and delicate passion flower (Passiflora arida) are among Erik’s edible offerings to the public. In addition to delicious treats, the Museum shares a great deal of ethnobotanical information about desert plants. Associate Research Scientist Jesús Garcia has been incorporating increasing amounts of ethnobotanical material into school kits and programs for the public. He points out that the Museum has always had a saguaro fruit harvest program, as well as strong ties to noted ethnobotanists such as Richard Felger, Mark Plotkin, and Gary Nabhan. Over time, public interest has been growing in learning how people have related to and used plants, and so have the ethnobotanical offerings of the Museum.

Jesús’ interest in plant-human relationships goes beyond the uses of plants in indigenous cultures. He helped spearhead the Kino Heritage Fruit Trees project, which grows plants brought to the region from the Spanish Mediterranean, such as pomegranate and citrus. Having grown up the Sonoran Desert south of the border, Jesús sees his own history and identity in the flavors of these plants, the blend of Hispanic influences on the desert, and indigenous traditions. The Kino Heritage Fruit Trees project exposes new transplants to Tucson to this rich history, which shows how personal identity has related to plants grown, eaten, and used in the region throughout history.

An interest in food crops native to the area is also increasing, especially in the light of climate change. Desert species are better suited to growing with less water for large food production as well as in gardens. The Museum has been involved with evaluating crops for desert agriculture and has observed an increase in the use of foods such as agave and mesquite by the public. A recent project highlights the plethora of food plants in the desert in the publication Desert Foods for a Resilient Future and is now set to expand. Wild, domesticated, and crop-wild relatives found in the Sonoran Desert offer opportunities to honor the past by understanding and exploring indigenous knowledge, as well as ways to prepare for a more arid future.

The benefits of desert crops—either native to the region or adapted from the Mediterranean or other sources—in the broader food system will only increase with climate change. Erik also sees the influence of climate change on a growing public interest in native gardens. Whether or not they attribute it directly to climate change, people are increasingly interested in how to save water and other natural resources. Jesús believes there is a greater awareness of the need to “understand the beauty of the place where you live, but also understand the nature in a way that [lets you recognize] that this requires less maintenance, less water, less money.”

At the Desert Museum, people find inspiration to become more in tune with nature and discover ways to create their own mini-Museum at home. Whether they focus on plants that draw in pollinators and other animals, or on plants that save water but are also useful or taste good, the desert has plenty to offer. Through plants cultivated for display and sale, and programs shared with the public, the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum encourages visitors to develop strong connections to their desert home and inspires them to live in harmony with it.

Restoring Native Coastal Prairie on California’s Lost Coast

Perched on the Western-most edge of California’s coastline—what is known today as the famous Lost Coast—elk historically grazed thousands of acres of native coastal prairies. Fire regimes kept natural succession from converting the grassland into forests dominated by Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), relegating the iconic conifer to riparian areas and isolated pockets throughout the region.

In the early 1900s, many of these prairies were still intact, providing abundant diversity and healthy habitats for species throughout the food web. Then the area began to experience dramatic land changes. Sheep grazing practices, while maintaining much of the natural prairie structure, decreased the diversity of natural species and introduced non-native annual species via imported feed. Later, tanbark harvesting and logging further reduced the natural diversity and threatened the well-being of the area.

And then the late 1980s arrived. An even greater ecosystem threat reared its head when fire suppression was enforced throughout the region. Unleashed from its hidey-holes in the drainages, the Douglas-fir marched into newly available and abundantly moist open areas. No longer beaten back by a fiery force, the conifer began a rapidly expanding encroachment. Within a decade, Douglas-fir dominated the coastal prairies.

The Mattole Restoration Council (MRC) was established in 1983 to address some of the concerns faced in the Mattole Watershed as a result of these land use changes. The non-profit MRC partners with local, state, federal, and non-governmental agencies to improve ecosystem health. Many projects have been implemented across the watershed, including here in the King Range National Conservation Area (KRNCA) near the Northern trailhead for the Lost Coast Trail on the precipice of the Pacific.

In 2008, the MRC partnered with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to instigate removal of encroaching Douglas-fir and coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis) and replanting with native species—particularly the perennial native bunchgrass species that previously had free reign over these rolling prairies. One such bunchgrass, known as Cape Mendocino reed grass (Calamagrostis foliosa), is endemic to the KRNCA and neighboring Sinkyone State Park—native exclusively to this secluded coastal community. This charismatic bunchgrass will make folks think twice about the grasslands that they generally see as an amorphous expanse of green. Clinging to cliff sides and waving cute fluffy flowers, it tests the limits of exposure and root-to-soil ratios while nestling in the heart of any true plant lover.

Another notable species in this area is western dog violet (Viola adunca), a native prairie-dwelling purple or white violet that grows low to the ground and can withstand the harsh coastal conditions of wind-blown bluffs. Despite its common name, this species is found throughout the U.S. It is the state flower of four states (Rhode Island, New Jersey, Wisconsin, and Illinois), is endangered in two states (Massachusetts and Connecticut), and is the host species of three federally endangered butterflies.

The MRC has achieved some incredible restoration on the Prosper Ridge area and throughout the KRNCA prairies since the project began in 2008. Encroached Douglas-fir and coyote brush have been removed from 350 acres, more than 300 large burn piles (each roughly the size of a single family home) have been burned, and over 260,000 native plants and 1,500 pounds of native seed have been installed. As part of an ongoing effort, the MRC looks forward to increasing its involvement with the local indigenous tribe (the Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria) and implementing prescribed fire, to ensure that these luscious coastal prairies provide for local populations for generations to come.

To learn more about the MRC and coastal prairie restoration efforts, as well as our native plant nursery and native seed farms, visit www.mattole.org or follow us on Instagram.com/mattolerestorationcouncil.

James Kwon

James Kwon has an enviable position that takes him across the Hawaiian and Mariana Islands, promoting the conservation of more than 170 threatened and endangered species that reside on military lands. His early experiences with botany and the wonders of diversity on the Hawaiian Islands helped shape his career path. We appreciate the Hawaiian proverbs he shares with us, which help us see the deep connection people have with plants.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I took a class on Island Biology, taught by Dr. Sherwin Carlquist, when I was an undergraduate at Pomona College. In addition to his research in Hawai’i, I was amazed by the examples of endemism and plant radiations/evolution on islands and island systems around the world. Going way back, looking under a microscope at cytoplasmic streaming in an Elodea leaf for the first time was pretty cool, too.

What was your career path to becoming a FWS Biologist?

During my M.S. program in Botany and Conservation Biology at the University of Hawai’i, I worked various part-time jobs in research and natural resources management. I interned at the U.S. Army Environmental Program on O’ahu, worked as a Co-operative Education Student for the Air Force, and participated in the restoration of Kahoolawe Island. For my master’s research, I studied the genetic variation of two rare Hawaiian hardwood trees in the Rhamnaceae (Colubrina oppositifolia and Alphitonia ponderosa), both given the native Hawaiian name, kauila. The trees were treasured by native Hawaiians for their dense, richly-colored wood that was crafted into weapons, musical implements, and kapa (barkcloth) beaters. Occurring in the dry and mesic forest ecosystems, both species are in decline due to ongoing threats, such as habitat loss, invasive species, fire, drought, and climate change. After completing graduate work, I continued working with the Air Force natural resources program until a position with USFWS became available. Though I was a “botanist” for many years, the positions were very generalist and I worked on a variety of projects. More recently I stepped into my current biologist position.

How would you describe your role as a biologist in the Pacific Islands FWS Office?

In my current role as a Fish and Wildlife Biologist, I serve as the Department of Defense Coordinator for the Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office. I work with all branches of the military to ensure Endangered Species Act compliance and promote conservation for over 170 threatened and endangered species—including 100+ plants—that occur on lands managed by the military in Hawai’i and the Mariana Islands. The work is challenging because, in addition to so many species, I work with so many branches of the military.

In its efforts to abide by the Endangered Species Act and the Sikes Act, the Army set the precedent in natural resources management in Hawai’i and has been the gold standard for some time. They have been on the cutting edge of strategy and able to invest a lot of resources. Along with other biologists in our office, we’re currently working with the Army as they re-evaluate their conservation program. We’re making an effort to keep the standard high, even as the training needs evolve. The majority of the 100+ plant species I mentioned above, occur on lands managed by the Army, so they are an important partner for conservation. It’s great that they are up for the challenge.

How do you communicate the importance of plants to people?

We all have a connection to plants. For the recently completed Hawai’i Rare Plant Genetics workshops, I was part of the group of FWS biologists who sought to establish connections between the indigenous knowledge and practices of native Hawaiians and plant conservation, through the use of ʻōlelo noeʻau, or Hawaiian proverbs. “I ulu nō ka lālā i ke kumu”—roughly translated “the branches grow because of the trunk,” or “without our ancestors we would not be here”—highlights the connectedness between people and plants. We see this connection in the story of Haloa, the first Hawaiian, whose older brother was a kalo (taro) plant. Another example is the Kumulipo, a cosmogenic and genealogical prayer or chant, which traces Hawaiian genealogy and links families to spiritual representatives of all phenomena—great and small—on the earth, in the sea, etc.

What has surprised you about working with and learning more about plants?

When traveling, I enjoy visiting natural areas and learning about the local flora. I’ve been struck by the incredible biodiversity and richness of the plant world. Yet there is overlap as well, with interesting connections between areas.

Plants are also incredibly resilient. It’s fascinating visiting the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Some of the islands were denuded 100 years ago as a result of invasive animals and extractive practices, but they are now maintained as wilderness areas and demonstrate a level of resiliency of the previous human disturbance and ongoing stressors such as invasive species and climate change. It is gratifying to see all the plants on these islands, and the birds they support.

In general, why do you support work to Save Plants?

I think it is important to conserve the incredible diversity exhibited by plants. Though we continue to learn about natural processes and systems and how they are sustained, there is so much more we don’t know. Systems are incredibly complex; with missing pieces, we do not know what will happen. We need to protect the processes that created such diversity.

I enjoy making lei using native and non-native flowers, and talking to people who ask about my garden plants as they go by. We all like to see how plants can be used in daily life—I think that can be key to increase public appreciation and knowledge of plants.

What new approaches or initiatives in conservation excite you?

There is so much going on! Species distribution modeling for surveys and planning purposes. Assisted migration to mitigate climate change impacts. Drone surveys to find and monitor new populations or otherwise inaccessible areas. Local organizations restoring areas, local nurseries growing native plants, ex situ storage techniques to prevent extinction, indigenous knowledge and worldviews to inform our work. There are so many exciting directions because saving plants is such a big task—especially in Hawai’i.

The Hawaiian proverb “ ʻAʻohe hana nui ke alu ʻia” translates to “No task is too big when done together by all.” Collaboration, interest, and passion across governmental and non-governmental agencies, botanical gardens, academia, non-profits, and private citizens is key to success. So, with the task before us and the many needs of rare plant resources, let’s continue to work together, build long-lasting relationships with each other, and deepen our commitment to the flora.

National Collection Spotlight: Pink Sand-verbena

Pink sand-verbena (Abronia umbellata ssp. breviflora) has the distinction of being the first North American plant collected and described from west of the Mississippi—plucked from Monterey Bay, California, on a 1786 scientific expedition. It was found all along the Pacific Coast, from northern California to British Columbia. Over two hundred years later, this species is imperiled—and even thought to be extirpated from British Columbia and Washington.

The pretty pink flowers pop up off succulent-leaved stems that sprawl across sandy beaches in California and Oregon. Populations of pink sand-verbena appear to be correlated with the snowy plover, a small native shorebird that may use this sand-verbena for forage and cover. Both species are impacted by habitat destruction caused by human activity and exotic plant invasion. The Institute for Applied Ecology has been working with pink sand-verbena for decades, including monitoring, seeding and translocation experiments, and population monitoring.

Rae Selling Berry Seed Bank’s early collection of pink sand-verbena made it a perfect candidate for CPC’s Seed Longevity Research effort, funded by the IMLS. Comparing a fresh seed collection to the original will help CPC partners understand how to best conserve this species and others for decades to come.

Learn more about the rich history of and conservation actions for pink sand-verbena on its National Collection Plant Profile, and support its conservation with a Plant Sponsorship.

As Seen on CPC’s Rare Plant Academy: Orchid Micropropagation

Micropropagation is an effective conservation tool for producing tissue clones or for germinating spore or seed in vitro. Orchids are known to be quite difficult to propagate, as they typically require fungal symbionts during their germination. In this video, Jason Ligon and Tito Tomei of Atlanta Botanical Garden explain how to propagate orchids in the lab using sterile micropropagation techniques. They show each step and emphasize how important sterility is for the process.

Watch more Rare Plant Academy videos.

This video was made possible through an IMLS grant.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Employment Opportunities

The Medicinal Plant Collections Research Scientist is responsible for coordinating and performing activities related to a) assembling a use-driven medicinal plants collection at the San Diego Botanic Garden; b) establishing a consortium of experts to advise the ongoing development of the collection; c) developing collection maintenance strategies and coordinating with partners to enable metabolite discovery; and d) establishing a publicly accessible medicinal plants garden for public education and engagement. The position will also perform other duties to advance SDBG’s science, conservation, and education objectives, to include acquiring new funding opportunities to potentially extend the position. This is a two-year, full-time (40 hours/week), exempt position with starting pay at $65,000-70,000 plus benefits per year. This position reports to the Senior Director of Science and Conservation.

Apply here: https://www.sdbgarden.org/employment.htm

Position: National Seed Strategy Coordinator

Location: Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Deadline: April 8, 2022

Overview: The National Seed Strategy Coordinator is a role responsible for development of a framework for a National Native Seed Strategy. The successful candidate will be capable of convening multi-stakeholder groups (indigenous, federal, provincial, territorial, municipal, non-profit and private partners) across Canada to facilitate the development of a Vision, Mission, guiding principles and values of a national conservation program that will enhance the way Canada achieves its climate change and biodiversity targets.

How to Apply: Cover letter and resume should be submitted online. See the full announcement: https://canadianwildlifefederation.applytojob.com/apply/4d3EcI76f3/National-Seed-Strategy-Coordinator

The Newingham Aridland Ecology Lab (http://newinghamlab.weebly.com) is seeking a full-time technician to assist with aridland ecosystem research. Our lab evaluates the effects of fire, climate change, and invasive species on plant and soil properties, as well as how restoration affects ecosystem recovery. The technician will primarily work on a project evaluating how fuel treatments affect subsequent wildfires and ecosystem trajectories; however, other projects include climate change effects on post-fire rehabilitation, wind and water erosion post-fire, and restoring native habitat in the Great Basin and Mojave deserts. We work closely with universities, state, and federal agencies to address natural resource issues and land management.

Job duties include:

● Oversee project management and personnel; coordinate activities with others in the lab and collaborators.

● Conduct ecological research by contributing to research design, establishing experiments, collecting data, and reporting results.

● Lead field crews and work in collaboration with graduate students and technicians.

● Data entry, management, and analysis; participate in scientific conferences; write scientific documents.

● Assist with hiring technicians, purchasing, and budget management.

● Conduct field research in remote and primitive areas under strenuous physical and climatological situations.

● Interact with scientists and land managers from state and federal agencies, such as the US Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, Nevada Department of Wildlife, University of Nevada Reno, and other universities.

Minimum Qualifications

● Education: BS degree in biology, ecology, natural resources, or closely related field. MS degree is preferred.

● At least four years of field ecology research experience.

● Previous experience with soil and plant sampling and sample analysis. Plant identification skills required; experience with soil sampling and micrometeorological equipment preferred.

● Strong knowledge of field plot establishment, monitoring, and experimental design.

● Experience with field and laboratory safety protocol and procedures, including basic analytical chemistry skills; maintaining and troubleshooting equipment.

● Experience with data management, graphing, and statistical analysis. Ability to use Excel, as well as other graphing and statistical software packages, such as R. Preferred knowledge of multivariate statistics.

● Experience using GPS and GIS (ArcGIS or QGIS) to locate and establish field plots, as well as conduct spatial analyses.

● Ability to contribute to written reports, peer-reviewed manuscripts, and give presentations at scientific conferences.

● Willingness and ability to camp and work in varied field conditions possibly for extended periods that may involve: 1) off-road hiking up and down hills, 2) carrying loads up to 30 lbs, and 3) withstanding periods of inclement weather during all seasons.

● Possess a valid driver’s license and experience operating 4WD vehicles.

● Demonstrated ability to work independently and in a group.

● Supervisory experience, including leading field crews.

● Ability to communicate with stakeholders and collaborators.

Employment and Application Information

The candidate will work with the USDA Agricultural Research Service and University of Nevada, Reno. The position is based in Reno, NV, with a preferred start date in May or June 2022 continuing for one year or more pending funding. Salary is commensurate with experience and includes health insurance, paid leave, and retirement benefits. Please send a resume, list of four references, unofficial transcript(s), and a letter detailing your skills, experience, and/or interest to Dr. Beth Newingham at beth.newingham@usda.gov. Review of applications will commence April 11, 2022 and remain open until the position is filled. Please contact Dr. Newingham with any questions.

The Abella Conservation Ecology Laboratory in Las Vegas, NV is seeking at least two full- and at least one part-time field and laboratory assistants/technicians to assist with desert and dryland upland and riparian vegetation monitoring and restoration projects in the west and southwest United States. Positions start May 1 or June 1, 2022 and end October 31, 2022 with the potential for extension through February 2023 pending additional funding. Positions will remain open until filled. The latest application date for a June start is May 1, 2022.

We have several summer projects, including assessing the effects of drought on desert ecosystems, assessing the effects of nonnative plant invasion and wildfires and fuels reduction treatments on P-J woodlands, determining if recent tree encroachment into meadows is a natural or recent phenomena due to ecological change, and assessing the effectiveness of native plant restoration in a desert riparian zone to promote plant and pollinator community recovery. We will be traveling to field sites in southeastern California, southern Nevada including the Gold Butte area, Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument, and Bryce Canyon National Park. During the fall, we will be conducting soil sampling at field sites in southeastern California and southern Nevada and conducing soil analyses in the laboratory, while continuing soil seed bank and seed ecology laboratory and greenhouse studies associated with the projects listed above.

Research assistants/technicians provide important support to research staff and UNLV graduate students by assisting with maintaining laboratory, greenhouse, and field components of projects. Project activities include botanical inventories, seed bank assays, seed ecology and pollination experiments, dendrochronology, soil analyses, and phenology and pollinator observations. These positions are professional contract positions and a great opportunity for early and mid-career professionals in ecology and botany. We will provide training and guidance to employees to achieve successful project participation, implementation, and management.

Minimum qualifications:

-A bachelor’s degree in the sciences, or biology, ecology, environmental science, or a related degree.

-If applying for a full-time position, some field or outdoor experience (e.g., previous field work, camping and hiking, or backpacking) is necessary.

-Be a United States citizen, have a current and valid state driver’s license, and have no personal at-fault accidents in the last three years.

Other qualifications:

At least two years field ecology research experience

Ability and willingness to camp and hike

Field navigation (GPS, map and compass) and 4WD experience

Experience with mapping programs, such as ArcGIS or Google Earth

Previous plant identification and soil analysis experience

Forest measurements and dendrochronology experience

Pollinator survey experience

Ability to work in a group or independently

Please feel free to contact us before applying if you have any questions. To apply, please send a CV or resume, two-three references, and a note to introduce yourself and extrapolate on your qualifications to Lindsay Chiquoine (lindsay.chiquoine@unlv.edu). Applicants are encouraged to briefly elaborate on their personal, academic, or professional experiences. Salary (full-time) and hourly (part-time) are commensurate with experience. Full-time employment includes benefits. Please include in the subject line the position “Research Assistant 2022” otherwise your email may be missed.

We actively participate in disseminating our research. Please see Dr. Scott Abella’s website to check out our recent work and publications: https://sites.google.com/site/scottrabella/

Ways to Help CPC

Support CPC By Using AmazonSmile

As many of us are now working from home and relying on home delivery more and more, we want to remind you that you can keep your home stocked AND Save Plants. If you plan to shop online, please consider using AmazonSmile.

AmazonSmile offers all of the same items, prices, and benefits of its sister website, Amazon.com, but with one distinct difference. When you shop on AmazonSmile, the AmazonSmile Foundation contributes 0.05 percent of eligible purchases to the charity of your choice. (Center for Plant Conservation).

There is no cost to charities or customers, and 100 percent of the donation generated from eligible purchases goes to the charity of your choice.

AmazonSmile is very simple to use—all you need is an Amazon account. On your first visit to the AmazonSmile site, you will be asked to log in to your Amazon account with existing username and password (you do not need a separate account for AmazonSmile). You will then be prompted to choose a charity to support. During future visits to the site, AmazonSmile will remember your charity and apply eligible purchases towards your total contribution—it is that easy!

If you do not have an Amazon account, you can create one on AmazonSmile.

Once you have selected Center for Plant Conservation as your charity, you are ready to start shopping. However, you must be logged into smile.amazon.com—donations will not be applied to purchases made on the Amazon.com main site or mobile app. It is also important to remember that not everything qualifies for AmazonSmile contributions.

So, stay safe inside, and when ordering online, remember you can still help save plants. Please feel free to share this email with your friends and family and ask them to select Center for Plant Conservation.

Thank you all for ALL you do.

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today