Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

January 2019 Newsletter

CPC’s model of collaborative work and a shared responsibility to Save Plants, a world first, has been used as the basis for other national and global efforts. At the core of this effort are the CPC Best Plant Conservation Practices to Support Species Survival in the Wild. These guidelines, developed over decades of intensive, shared work, are used by CPC Participating Institutions and many others around the world to save plants from extinction.

To date, we now have over one third of North American imperiled plants (1,500 of 4,400 kinds) secured in the CPC National Collection of Endangered Plants. This work has led to the most advanced and effective set of plant conservation guidelines in the world. Challenges such as seed storage, plant propagation and preservation/recovery of species in the wild, are all being addressed by CPC partners and find their way into each new iteration of the guidelines. In doing so, we continue to advance the science of saving plants. And with our new online, interactive capacity for the guidelines, we now will continually update these in real time to better than ever share relevant and timely conservation methods with all those who use them to Save Plants.

In this month’s issue of SavePlants, we highlight the tools and techniques that are on the cutting edge of plant conservation science, encapsulated and shared via the CPC guidelines. From cryopreservation to advanced genetics, plant conservation involves far more than collecting and growing out seeds. Read on to understand more about what it takes to Save Plants and marvel as many of us do at the expertise and dedication the CPC network has to offer our world!

Strategizing Collections with Genetic Research Montgomery Botanical Center

Trekking around the world to amazing habitats palms and cycads call home to make collections, the staff at Montgomery Botanical Center strive to make sure those collections truly conserve the genetic diversity of these diverse and fascinating groups of plants. Patrick Griffith and his team are using model species to study the genetics of collections to help them tackle the fundamental problem on developing conservation collections — which plants and how many?

The 120 acres of the Montgomery Botanical Center (MBC) on the bay in a quiet neighborhood in Coral Gables, Florida, are home to thousands of palms and cycads, as well as other tropical species in their care. Many of these majestic plants are part of conservation collections, that is a collection of seeds, tissue or whole plants that supports species’ survival and reduces extinction risk. But conservation collections require many plant individuals from the same population to fully conserve the genetic diversity of the species that occurs in the wild, and 120 acres quickly seems small when you’re trying to conserve several species. Space and other limited resources drive fundamental questions about these collections that beg answers: which plants should be grown? How many plants do you need to collect to maintain a conservation collection? Fortunately, MBC had the staff and funding support, including a few key Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) grants, to start answering these questions.

Starting with key thatch palm (Leucothrinax morrisii) as a model, Patrick Griffith, director of MBC, and his staff set to work trying to figure out just how many palms were needed to capture the genetic diversity found in the wild. To do this they looked at microsatellites, or distinct repeats within a sequence of DNA that have relatively high rates of mutation, to identify population genetic markers and compare the ex situ (off-site, not wild) collection with its wild counterpart. They found that the more individuals in the collection, the more genetic diversity saved – up to a point. Eventually the benefits of adding another individual to the collection start to taper off… and for key thatch palm this occurred at a surprisingly few number of plants (15!). Key thatch palm was a good general model because it is a monoecious, (having both male and female organs in same plant) wind-pollinated, and widely distributed species, but many species – especially many rare species – don’t fit that model, limiting its application. So, for the next round of research they moved on to rare cycads with very different biology.

They turned to sinkhole cycad (Zamia decumbens), a rare species occurring with just a few small populations in southern Belize. Partnering with the Belize Botanic Garden and drawing on the support of Dr. Lin Lougheed and his generous support of MBC’s Plant Exploration Fund, Dr. Griffith and his staff collected genetic samples from the ex situ (collections) and in situ (wild) populations of the cycad. Using the same techniques as with key thatch palm, they found that the added genetic value of collecting more individuals tapered off at over 200 individuals… a far cry from the palm’s result. It was at this point that Dr. Griffith realized that there was not going to be one right answer: people making conservation collections will need to consider the circumstances and biology of the plants they are striving to save.

Some general guidelines did emerge – that populations should be managed separately, that gardens should collect and maintain multiple accessions, and collect over multiple seasons. For sinkhole cycads, a consideration of its reproductive biology pointed to the need to make collections over multiple years, as only a handful of cycads may be producing seed in any given year.

Every plant species is unique, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t value in learning more from model species. Comparing sinkhole cycad to a related cycad, bay rush (Z. lucayana) with very different circumstances (one continuous population in a restricted habitat, a different life history, etc.), reinforced the idea that each species’ biology should be considered. Yet, still a very high number of individuals would be needed to capture diversity. It proved very valuable to do a pair-wise comparison of these related cycads to better inform collection strategies for other similar species.

Now MBC is moving forward with the pair-wise approach under a new IMLS National Leadership Grant, along with several US and international partners. MBC will work with the Bahamas National Trust, the Rafael Moscoso Botanical National Botanical Garden in the Dominican Republic, Belize Botanic Gardens, and the USDA-ARS to examine two more rare palms, buccaneer palm and cacheito (Pseudophoenix sargentii and P. ekmanii). Meanwhile, Chicago Botanic Garden, CPC, BGCI, National Tropic Botanic Garden, and the Morton Arboretum will tackle the genetics of oaks, magnolias, and hibiscus – each in a pairwise comparison. Though a broad spectrum of trees, all of these are long-lived species with limited seed banking potential, the types of species where the questions of which plants and how many are particularly important for ex situ collections. The project is already generating some good results. Soon, there will be more information out there on determining optimal level of genetic capture for trees that can be managed within a garden’s resources… helping more gardens save more plants.

Learning from Monitoring: Improving Plant Reintroductions Over Time Missouri Botanical Garden

Reintroductions are tricky, but also an important opportunity to learn about the species being reintroduced. Using lessons learned from nearly 20 years of working with Pyne’s ground plum, and drawing on information about reintroduction efforts from across the CPC network, Dr. Matthew Albrecht has learned the importance of using long-term monitoring to learn more about rare species and using that knowledge to manage their reintroductions.

John Harper, the world-renowned British botanist and ecologist, once famously said that “plants stand still and wait to be counted.” Many of our conservation colleagues in the CPC network know this quote well: we have spent many hours in the field bending over, crawling on rough terrain, and sometimes contorting our bodies in unimaginable yoga-like positions to locate, measure, count, and monitor imperiled plant species. Year after year we revisit the same population sites, tracking the survival, growth, and flowering of individual plants. Over time, this seemingly mundane task helps us understand the long-term health, status, and population trends of our beloved wildflowers. Importantly, monitoring reveals whether our conservation actions are making a positive difference, or whether we need to adjust our methods and techniques to improve the long-term survival prospects of a species in the wild, a process known as adaptive management.

For nearly 20 years, the conservation team at the Missouri Botanical Garden has been involved in monitoring populations of the endangered wildflower, Pyne’s ground plum (Astragalus bibullatus). In 2001, my predecessor Dr. Kim McCue (currently Director of Research, Conservation, and Collections at Desert Botanical Garden), initiated an experimental project to reintroduce populations of Pyne’s ground plum, which was tottering on the brink of extinction, to select sites in Tennessee. Although those reintroduced populations eventually dwindled in size, they were not without benefit. Careful monitoring revealed important information on how individuals performed when planted at different times of the year and from different genetic origins – information that was applied in subsequent reintroductions. Through repeated experimentation and monitoring, the process of adaptive management has continued and taught us those early reintroductions dwindled because the geology and hydrology was unfit for Pyne’s ground-plum at those sites. More recent experiments show the importance of herbivores, soil microbes, pollen limitation, and light-gaps on growth, flowering, and fruit set; data that will influence the design of future reintroductions.

Many of our CPC colleagues are similarly involved in long-term reintroduction projects that apply an adaptive management framework. They have generously shared monitoring data with me and my team of collaborators so we can learn more about what helps plant reintroduction succeed and share that information more broadly. With this wide-ranging data set we looked at how different life-histories, pollination mechanisms, seed dispersal syndromes, seed production rates, and so on, might influence rates of seedling recruitment in plant reintroductions. Seedling recruitment is an important indicator of success, as it demonstrates that reintroduced plants can cross-pollinate, set seed, and that the site conditions can support the next generation. Early work on reintroduction success of CPC species focused mostly on the establishment of ex situ propagated plants at reintroduction sites, rather than on longer-term success metrics. But the true goal of reintroduction is to establish a healthy, self-perpetuating population, which isn’t always a given once propagated plants have established.

Previously, CPC’s guidelines simply recommended monitoring reintroductions for a minimum of three years and, if possible, for ten years. Yet our analyses of the CPC reintroduction data, recently published in Conservation Biology, suggests this timeframe is probably far too short for some imperiled species. It turns out that some plants live life in the fast lane. Individuals of these species are short-lived, grow and reproduce quickly, and recruit new seedlings within a matter of a year or two after reintroduction. For example, species adapted to fire often had the highest recruitment rates. Other plants live life in the slow lane. These tend to be species with long-lived individuals that grow very slowly, investing in large root reserves to survive in place over the long haul. Such species often experience long lag times before new seedlings ever appear in reintroduced populations. A classic example is the reintroductions of Mead’s milkweed by our colleagues, Marlin Bowles and Tim Bell, at the Morton Arboretum. This slow-growing grassland endemic takes many years before reintroduced individuals reach reproductive maturity. Once they flower and set seed, though, another decade or longer may pass before a seedling recruit makes an appearance. CPC’s updated guidelines reflect the difference in monitoring requirements for different species to ensure long-term success.

Back in Tennessee with our Pyne’s ground-plum reintroduction program we are beginning to see glimpses of success, after repeated cycles of adaptive management. Recently reintroduced populations are thriving and flowering, but we now know that Pyne’s ground plum lives life in the slow lane. Like Mead’s milkweed, monitoring must continue for several years before we will likely ever observe a new seedling recruit. The lessons we have learned from this project and those of our CPC colleagues reminds me of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s call to “Adopt the pace of nature: her secret is patience.”

Branching Out For Oak Conservation Morton Arboretum

Over 30 percent of tree species globally have seeds and can’t be saved through seed banking – including all oaks. Fortunately, Murphy Westwood, Director of Global Tree Conservation and her team of researchers and collaborators are working towards making the most of living conservation collections to protect these important trees.

As people who love plants, we know that plants, as a rule, are pretty amazing. But some are exceptional. In the world of plant conservation, this means that seed banking is not suitable as a long-term ex situ (off-site, not in the wild) conservation technique for these species. This may be because the seed cannot be dried down (i.e. recalcitrant seed), the seed doesn’t last long in storage, or that reproduction of the species does not provide sufficient seed. Whatever the reasons, other forms of ex situ conservation need to be used to help us save these species: one of the main alternatives to seed banking promoted for tree conservation is the creation of conservation groves, or field gene banks, which capture the genetic variability of wild populations in living plants. Murphy Westwood, Ph.D., Director of Global Tree Conservation, and her team at The Morton Arboretum (and beyond) are working to expand and improve conservation groves of one group of exceptional species, the oaks.

Oaks are in dire straits. The updated IUCN Red List, a internationally recognized list of world’s endangered species, identifies one quarter of our native oak species in the U.S. to be of conservation concern. This number is likely to be much higher in the two global diversity hotspots for oaks – Mexico and Southeast Asia. Westwood and her team are spearheading the global effort to Red List the world’s ~450 oak species and expect to have the assessments complete by the end of the year.

Oaks can be challenging when it comes to managing conservation groves as many require a lot of space, they readily hybridize with other oak species, and though they are popular in gardens, their provenance is not always known. To discuss and address some of these issues, it makes sense to collaborate. Thus one of the things Murphy is working towards is establishing a Conservation Collections Consortium for Oaks for North America.

-

Shinnery oak grows atop a rocky outcrop in Cedar Mesa, UT. Photo credit: Sean Hoban, courtesy of the Morton Arboretum. -

Sean Hoban in the field with shinnery oak (Quercus havardii) in Fall Creek. Photo credit: Sean Hoban, courtesy of the Morton Arboretum. -

A shinnery oak (Q. havardii) acorn from Cedar Mesa, Utah. Photo credit: Sean Hoban, courtesy of the Morton Arboretum.

The consortium includes not just botanical gardens, but crosses sectors. Nursery managers, U.S. Forest Service staff, private collectors all have collections and knowledge, and a desire to contribute to the conservation of oaks. Murphy states that securing a diversity of partners was an important goal, and an exciting aspect, of the initial meeting held this past fall at the International Oak Society Conference, held at UC Davis Arboretum and Public Garden. The idea is to make the group broad and welcome participation at many levels. A small garden could hold a few individuals of one population, whereas a federal or state facility may be able to support hundreds or even thousands of individuals across several species.

While still formalizing the consortium, Murphy and her partners have already identified some tenants, and set to work on some species. Drawing on the CPC’s Best Plant Conservation Practices to Support Species Survival in the Wild, they are outlining their best practices and expectations for participants, and defining what success is going to look like. Not waiting for molecular genetics studies on all species, the group is making an effort to capture the geographical and ecological spread of each species. The collections will be spread across multiple institutions and be available for research, breeding, providing restoration material, and for educational outreach. A conservation collection may have a single institution taking the lead, but consist of 50 or up to 100s of individual trees housed across gardens 100s of mile apart, and even have the possibility of those gardens spreading their portion of the collection more locally to partners such as schools, retirement communities, and other “non-traditional” gardens.

In finding the right number of trees per institution, there is a tradeoff between spreading the risk of damage to any one site and the need to have multiple individuals together. Something that will help with this is using the ‘stud book’ approach towards breeding within the collections (discussed in November 2018 issue). Hopefully, this approach will allow the consortium to maintain a coordinated conservation collection across many institutions through generations without losing the genetic variation of the wild population.

There is much to consider when planting conservation groves, especially, of such long-lived species. And the Consortium is providing great opportunities for research. The Morton Arboretum is a hub of oak research, with the group being one of their flagships. Some of their research, and that at Dawes Arboretum is prompting the group to consider climate change when thinking through host institutions of the conservation groves. Some southern and southeastern species can just about survive in Chicago currently, but in 80-100 years, they may actually thrive there. Some of the species, including Oglethorpe oak (Q. oglethorpensis), Georgia oak (Q. georgiana), and the endangered maple-leaved oak (Q. acerifolia) have already had acorns collected with good representation and are getting a good start in the Morton nursery.

Some of the other research The Morton Arboretum is taking on in conjunction with this project centers on the population genetics of shinnery oak (Q. havardii), a highly clonal oak that ranges across three states in the southwest in fragmented populations. With this research, Arboretum researchers led by Sean Hoban hope to inform the consortium’s strategy to most efficiently represent the geographic and ecological ranges of a species to ensure genetic variability is being captured in a conservation collection.

Through collaboration, we can do more and learn more, to save oaks and other exceptional plants!

If your plants don’t have records, do they exist? San Diego Zoo Global

Rare plant collections require a daunting combination of skill, time, and luck. To ensure that this hard work provides the maximum possible value to the conservation community, collectors must maintain detailed and shareable records.

Philosophers have long asked, “If a tree falls in the wood and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” As a plant conservationist, it’s hard to answer this question without a botanical bent: For me, the death of a plant (especially a rare one!) makes a philosophical and ecological impact that can be “heard” even if no one directly observes it. This belief is shared by our community of conservationists who scale cliff faces, trek through brambles, and endure mosquitos-laden swamps to collect the seeds that ensure the survival of rare plants species. During these hectic field trips, the mundane process of recording details about the location, habitat, and habit of the plant may fall by the wayside. Similarly, the data entry of field records might take a back seat to day-to-day work place deadlines. However, to all those with data languishing un-entered in their lab or green house I ask, “If you collect a plant and no one has time to document it, does it still have conservation value?”

Without detailed, shareable plant records, a plant collection is unlikely to help save a species from extinction. For instance, location information is critical to assessing where a population of plants could be reintroduced in to the wild, and germination records are the best way to estimate the quantity of seeds needed for such an effort. In addition, sharing plant records across institutions can prevent duplicate collections of already rare plants species, and ensure that the limited resources available for plant conservation are being used efficiently. Finally, plant collections records are the basis of much of the current research into species distributions and migrations due to global climate change. By providing accurate collections data, conservationists facilitate additional research about the rare plants they are working to save.

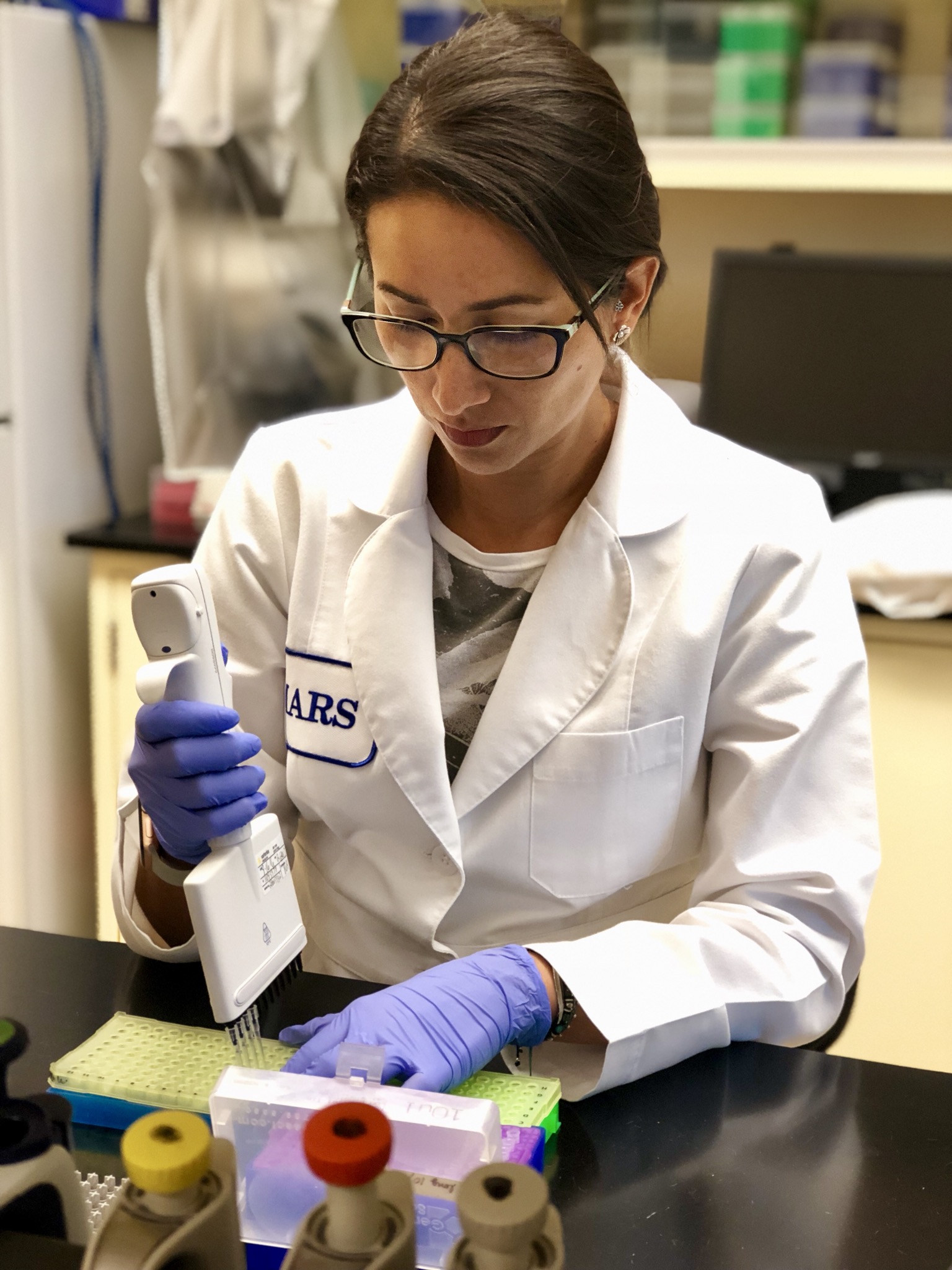

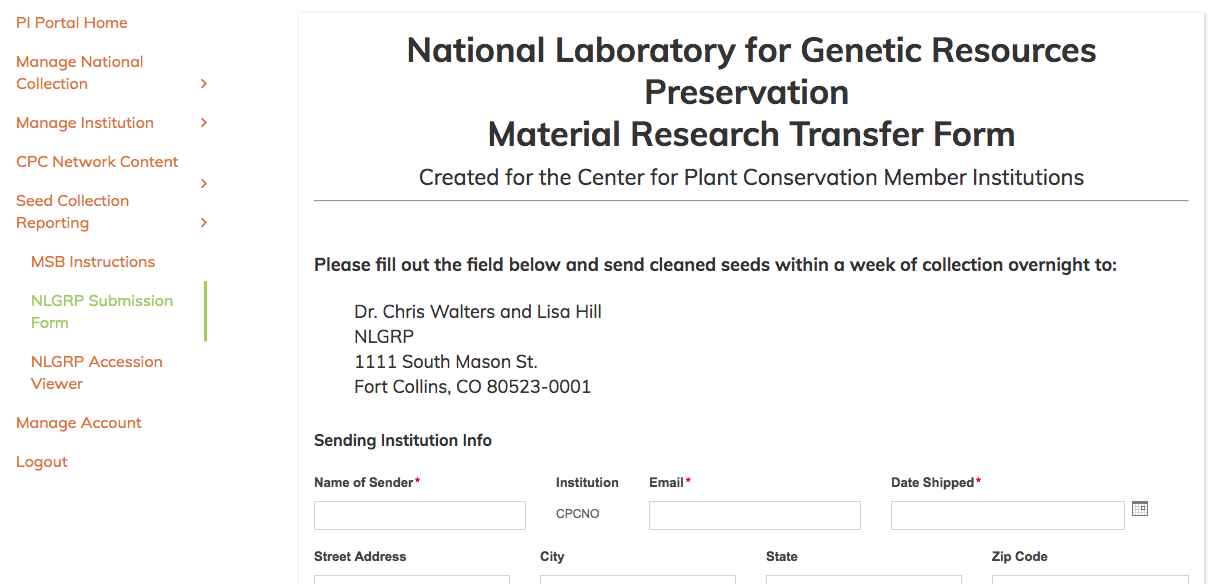

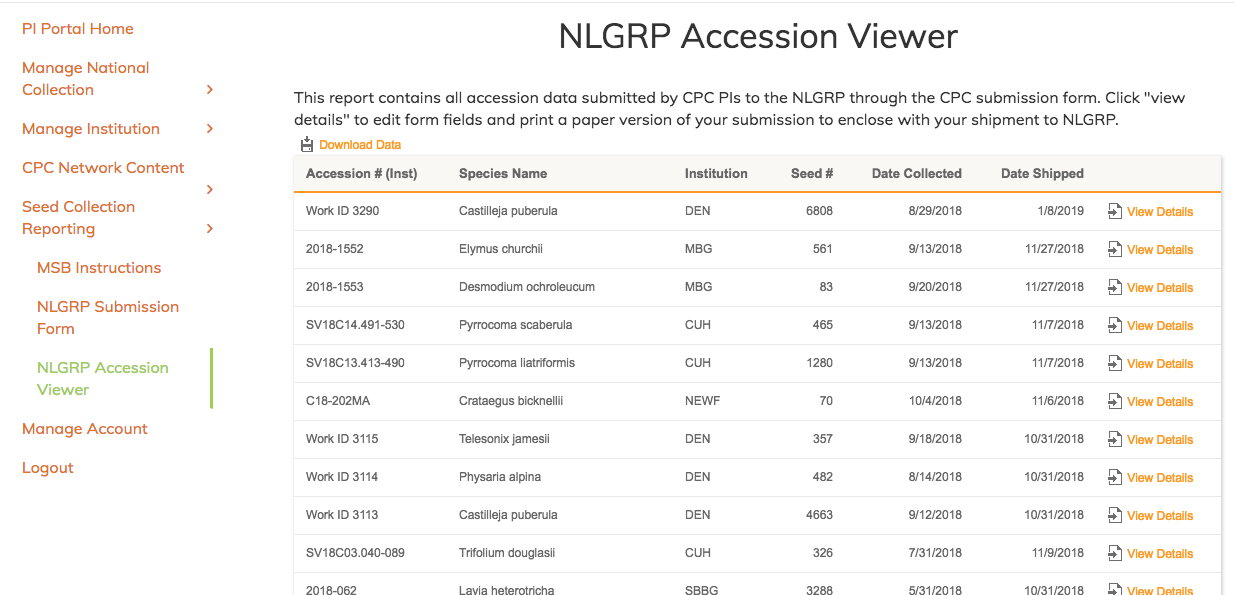

CPC has developed a set of tools to help our network of plant conservationists record and share high quality rare plant records. In the “Documentation and Data Sharing” portion of CPC’s Best Plant Conservation Practices to Support Species Survival in the Wild, our best practices guidelines, we provide a field collection form that outlines the information that conservationists should make at the time of each plant collection, as well as describe other best practices for data collection and management. We also provide an electronic form in our CPC Participating Institution (PI) web portal that allows CPC Conservation Officers to transmit collection data directly to the National Laboratory for Genetic Resource Preservation (NLGRP), where our institutions send “back up” allotments of rare seed. By using this form, our PIs are not only facilitating the seed research of NLGRP, but they are also communicating their collections with a community of plant conservationists. Sharing data helps track progress on collective goals and allows for more people to learn from the data.

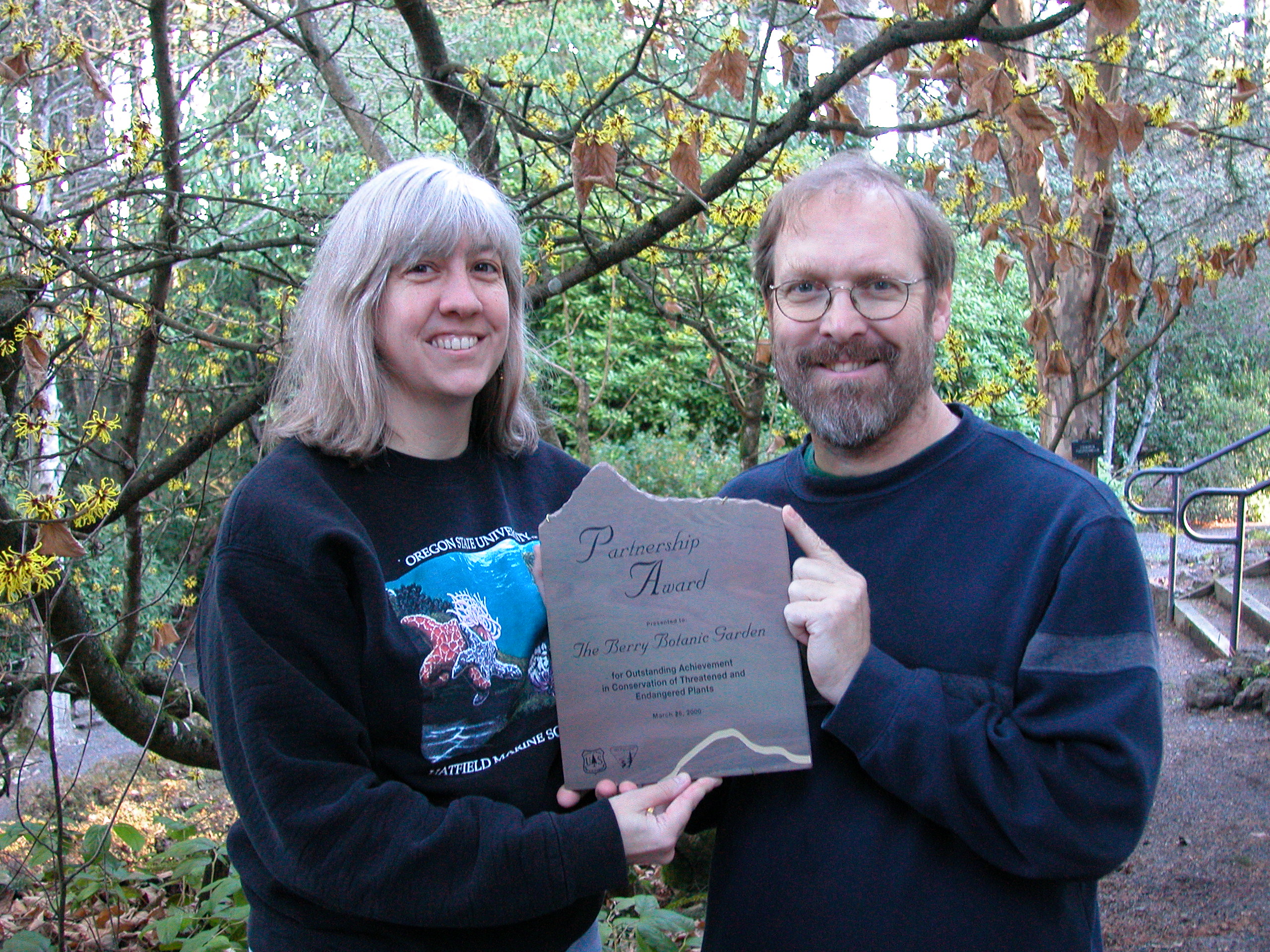

Ed Guerrant, Ph.D.,

The CPC family pays tribute to our friend and colleague Ed O. Guerrant, Jr. as he embarks on his new adventures in retirement. Ed’s contributions toward refining our best practices for ex situ care and defining CPC values and ethics are part of his lifelong legacy to plant conservation. – Joyce Maschinski

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I can’t remember a time when I didn’t love the out of doors. Growing up in the suburbs east of Los Angeles in the 1950s, I spent a lot of time outdoors. We lived close to the mountains and had a family cabin in the San Bernardino Mountains. From the more intellectual side of things, I was a junior zoology major in college when I took a plant biogeography class. That did it, and I soon became a double major in Zoology and Botany. A two quarter plant taxonomy class with C. Leo ‘Hitchy’ Hitchcock sealed the deal.

What was your career path in becoming Director of the Rae Selling Berry Seed Bank and Conservation Program?

My career was more a result of a series of unpredictable events than any sort of intentional path. After I finished my PhD in Botany, I followed my girlfriend, later wife and mother of two wonderful children, and moved to Portland, OR. I taught biology, ecology, genetics and evolution as an adjunct at Lewis and Clark College from 1986 to 1990. The Berry Botanic Garden – a small 6-acre estate garden – was only a mile away from Lewis and Clark College and historically a faculty member sat on its board. The other two botanists had done it several times each, so I was recruited.

I joined the board at a tumultuous time for the Garden. We were transitioning between Executive Directors, with the new hire unable to change coasts for many months. During this time, my predecessor suddenly and unexpectedly resigned. Not surprisingly, the board was distressed. But I had what I thought would be the perfect solution: hire me.

Thrilled with the idea of working in plant conservation overall, I was initially skeptical about the practice of ex situ plant conservation: taking seeds out of nature to protect them in nature seemed sketchy. It was a question I thought about a lot, and along with others, this quest eventually led, at least indirectly, to the CPC book Ex Situ Plant Conservation: Supporting Species Survival in the Wild. The subtitle alludes to the solution: ex situ methods are not an end in themselves, but a means to an end.

The book you co-edited, Ex Situ Plant Conservation, provided a base and framework of the recently updated CPC guidelines. Can you tell us a little about how that book came about and the process of putting it together with your colleagues?

The idea for the book occurred at the 1996 CPC annual meeting, in Denver, CO, arising out of a conversation I had with Kay Havens and Carol Dawson. We perceived a need to fill the gap between collection and reintroduction that then existed in the first two CPC books. It grew from there, ultimately in the attempt to address storage, to complete the trilogy: collect, store, and if necessary, use. We also wanted to address broader strategic issues of how, in plant conservation overall, ex situ plant conservation fit into the larger scheme of things.

Carol was unable to continue, but Kay and I, feeling the need for an international perspective, invited Mike Maunder, then at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, to join us.

One thing that I didn’t realize before we outlined the book, and the associated symposium at the Chicago Botanic Garden, was how creative an endeavor it is to edit a book. I had naively thought of it as simply editing chapters that other people wrote. I was pleasantly surprised to find a lot of creative opportunity in the conception and organization of the book, and the conference on which it was based. Island Press was wonderful to work with, and instilled in us the need for the book to cohere as a larger whole. They helped keep us grounded and moving forward.

What are a couple of the major threats/challenges facing rare plants in the Pacific Northwest? How has your/your institution’s work addressed them?

It depends on scale in time and space. In the near term, it is the regular suspects: habitat destruction, effects of invasive species.

In the longer term, and, like the high wispy cirrus clouds in an otherwise blue sky that announce the coming of a warm front, we are beginning to see the first wispy effects of global climate change in the increased intensity of extremes in temperature and precipitation. This realization led us at the seed bank to begin adding seeds of more common species to our ongoing efforts with rare species.

What about working with seeds/seed banking has surprised you?

Perhaps the most unexpected aspect of working with seeds and seed storage is the astonishingly diverse array metaphorical connections they have to so many aspects of life. It is not much of a stretch to think that agriculture as we know it could not have happened without some means of saving seeds for use in later years. Some have suggested that early community seed storage facilities in ancient Egypt might have contributed to the origin of currency, and the concept of credit, are based on them. Like money, a quantity of grain is fungible, making it and easier means of doing business than barter.

More broadly, I think Gary Paul Nabhan sums it up beautifully: “We need seeds because they are the physical manifestation of the concept we call hope.”

Please share one of your plant conservation success stories.

Rather than any one project, I find success in the tremendous growth of the Berry Seed Bank, and in the improvement I have seen in our seed bank practices. The Berry Botanic Garden Seed Bank for Rare and Endangered Plants of the Pacific Northwest which began with an exclusive focus on rare and endangered plants, has expanded to include more common plants as well.

What accomplishment are you most proud of achieving in your career?

I would like to think my work was important in establishing the practice of collecting and maintaining seed samples by maternal line, as opposed to bulk collections (with apologies to so many whose work load was increased by the switch from bulk collections. I feel your pain.)

How has the world of plant conservation changed throughout your career?

Perhaps the biggest change was the increased scientific and technical rigor, due in no small part to the CPC itself. When I began this work, the Berry Botanic Garden was a tiny, out of the way estate garden that had a seed bank. Although trained in botany, ecology and evolution, I didn’t really know anything in particular about collecting and banking seeds, or the role ex situ methods played in the larger plant conservation picture.

I found in the CPC annual meetings a fabulous group of conservation practitioners and scientists, who formed the essential core of my professional community.

Through its experience and the books that experience has informed, the CPC is a world leader in the development of ex situ plant conservation of rare plants. I have been privileged to have my career begin early in this process, and thus be able to play a part to help conserve rare plants in the USA and around the world.

In what area of plant conservation do you see the need for research and hope someone picks up?

The specter of global climate change has begun to emerge as perhaps the most significant threat to biodiversity with which the world’s ecosystems have had to contend, certainly during the lifetime of the human species.

I think the CPC is well positioned to serve as a catalyst to help develop an expanded vision and methods to include currently common species. Assuming climate change will cause serious ecological disruption over the coming decades and centuries, what sort of collections will our descendants one, two hundred years from now value the most?

What are you looking forward to most in retirement?

First, I’m looking forward to less stress and to having more time for other pursuits than working as much as I have. Ultimately, I want to travel more and get back to drawing and watercolor painting. I’d like to combine travel, art and whatever professional plant conservation skills I have, and put them to use in different places.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today