Save Plants: February 2020 Newsletter

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

February 2020 Newsletter

One of the important reasons for saving rare plants from extinction is that a healthy natural world promotes human well-being. In urban settings, gardening can help connect people to nature around them, and the gardens can help pollinators. Helping insects thrive in a native plant community will help rare plants, because many generalist pollinators visit both common and rare plants. Planting native plants in one’s home garden is a very good thing to do. Yet there are some important biological reasons why all of us should be aware of the source of the native plants we buy commercially for our gardens. From an insect’s perspective, one milkweed is not the same as another. In some cases, a southern source of a host plant can be very different from a northern source. Explore this issue of Save Plants to understand how urban connections to nature are being formed in South Florida, and how your home garden may become part of a solution – especially if you understand the nuances of what it means for a plant to be native.

Joyce Maschinski

CPC President & CEOConnect to Protect Network for Pine Rocklands

When asked to picture the habitats of Florida, a non-Floridian will likely think of sandy beaches or the swampy forests of the Everglades. Pine rockland doesn’t fit this typical image, yet the pine rockland plant community of South Florida once covered hundreds of thousands of acres of Miami-Dade County. This unique plant community brings together temperate and tropical species, with pines, palms, and several rare herbaceous species in the understory. Unfortunately, only 2% of the county’s pine rockland remains today. Much of it has been lost to development, and the existing fragments are often denied processes such as fire that are needed to maintain populations of some of the rare understory species.

Restoration options are limited by special substrate requirements – the rocks of the pine rocklands are actually ancient coral reefs. This habitat is restricted to South Florida, the Keys, and a handful of Caribbean islands. Happily, Joyce Maschinski (now Executive Director of CPC) came up with a novel approach when she was working on conservation of pine rockland endemics at the Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden. It occurred to her that the plants of this globally imperiled ecosystem can be supported on their native soils by using the yards, parks, and right-of-ways that dot the urban and suburban landscape of Florida.

Starting in 2007, Joyce worked to build the Connect to Protect Network, which promotes planting some of the 400 plant species in these public and private spaces to better connect remaining fragments of the pine rocklands. The program uses education and outreach – and free plants – to increase awareness of the benefits of planting pine rockland natives and encourage locals to learn and experience more of their local environment.

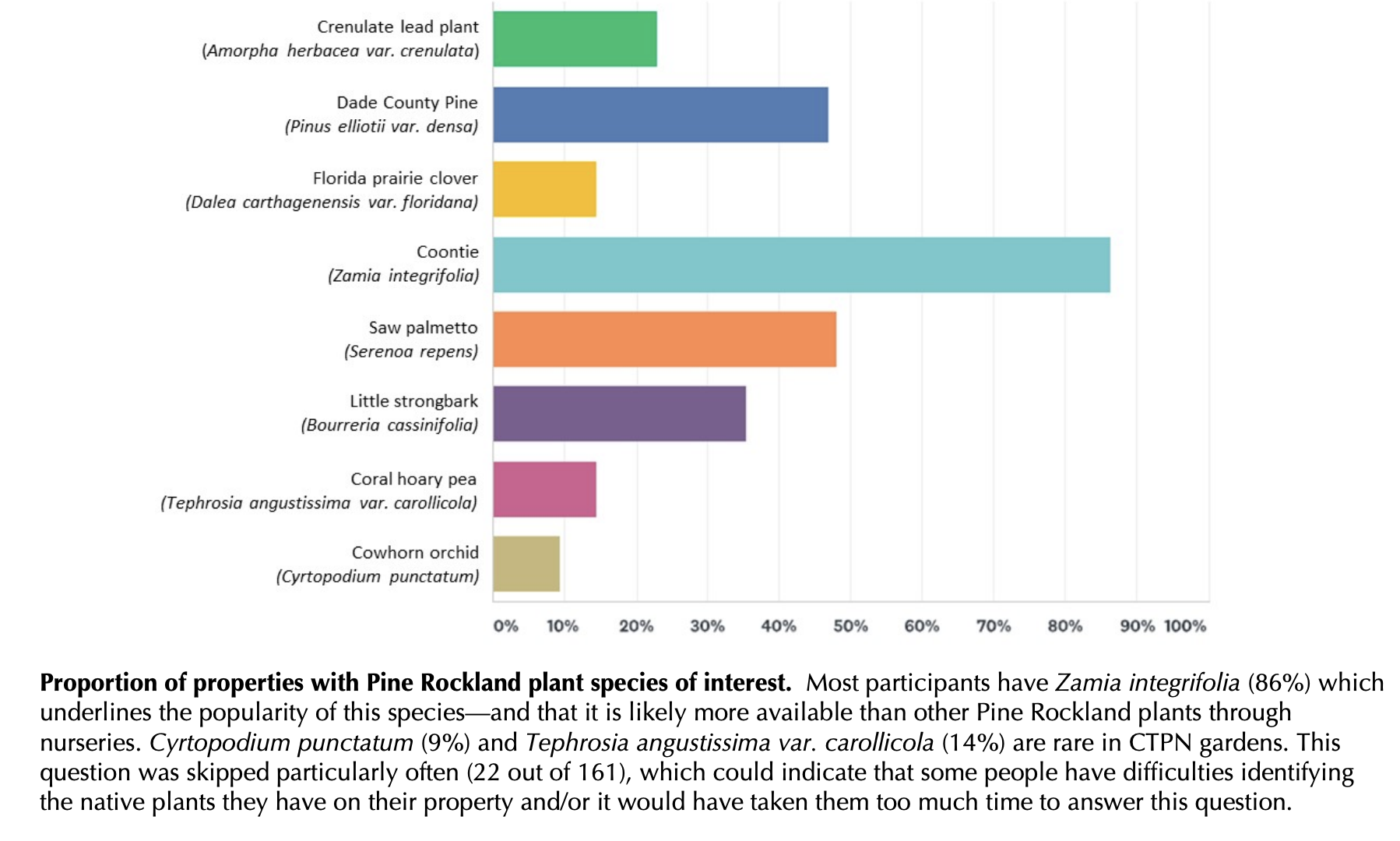

The success of the Connect to Protect Network has inspired other institutions inside and outside the CPC network to develop similar programs. During CPC’s 2019 National Meeting, Fairchild’s conservation officer Jennifer Possley reported on the lessons learned in administering and expanding the program. Fairchild, like every nonprofit, has worked hard to grow programs despite limited resources, and the program has quadrupled since 2015. Now nearly 700 members participate in the Connect to Protect Network across Miami-Dade County – growing and promoting the special flora (and fauna) of the pine rocklands.

Lessons Learned in Growing Connect to Protect

1. Conserve your energy.

Don’t try to give personal attention to everyone… but do make good information available to everyone. The program makes commonly needed information available online, including locations of native plant nurseries and a restoration guide. In offering events, the program connects members to experts to make sure they are getting the advice they need to succeed. With hundreds of people in the network or expressing interest, you will be overwhelmed if you try to attend individually to everyone. A better approach is to anticipate needs and get information out in other ways. Events provide opportunities for participants to learn more about the program, select new plants, and get advice from the experts.

2. Control your image.

Images are powerful – they can attract new members and deter others. In trying to draw in participants who aren’t hardcore naturalists, you should be aware that the cool endemic snake may be a deterrent. Some members will embrace the habitat idea and be unconcerned with aesthetics of their garden, but others may be discouraged by a perceived inability to achieve a conventionally attractive yard. You can avert this by providing expertise and examples, and use a photo contest to capture and share the results. A Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden photo contest helped gather attractive photos of native plant gardens to help entice new participants. Here are the top three winners from the contest held by the garden.

3. Don’t do it yourself.

It may take a while to find the right help, but it’s worth finding good staff, volunteers, and strategic partnerships. Being open-minded to new ideas from potential partners can open the door to greater success.

How native is that native?

Monarch butterflies are perhaps the most well-known butterflies in North America, with their eye-catching orange and black patterning and huge swarms that strike a chord in the public’s imagination. Millions of butterflies migrate each year to winter in warm areas of the U.S., including California and Baja California. Their numbers have been declining drastically, however. The Xerces Society reported a 97% decline in butterflies from the 1980s to the 2010s. This report spurred gardeners across the country into action, eager to help the butterfly by making up for lost habitat and planting caterpillar food – milkweed – in their gardens.

Unfortunately, the local nurseries only had tropical milkweed (Asclepias curassavica) to offer. While the caterpillars ate it up, the impact on the butterflies was not positive. The tropical milkweed doesn’t die back, offering a breeding ground year-round for monarchs (who then may not migrate) as well as for parasites of the butterfly. The tropical milkweed plantings were actually leading to parasitic infections in adult butterflies and potentially leading to further decline. The simple solution would be to provide native milkweed for gardeners, yet it turns out to be not so simple. One has to ask, how native is native?

Is it native if it occurs in your region, state, county, or within a 20-mile radius, or if it would likely thrive in local conditions? Wikipedia sums up what many native plant websites describe: “Native plants are plants indigenous to a given area in geologic time. This includes plants that have developed, occur naturally or existed for many years in an area.” While helpful, this definition does not address issues that may arise when plant species occur across a wide range or are native to a general area but have specific habitats. Populations of a species that occur across a wide area may have adapted to specific local conditions and may not thrive if planted in other areas, even those within the species range.

I have been working on a project in Southern California to plant natives that will assist the recovery of the struggling Western Monarch population. The obvious solution is to plant native milkweed (Asclepias) species, which provide food for caterpillars, in addition to native nectar sources. California botanists have identified 16 distinct species of milkweed native to the state, six of which occur in San Diego County, the site of my project. Of these six species, five are predominantly found in the desert or mountain habitats of the county, while only one ranges from the coast to the mountains –where most of the people hoping to promote monarchs live.

-

Narrow-leaf milkweed (Asclepias fascicularis) looks quite different in foliage from its common cousin. Though naturally ranging throughout southern California, it is also found further north. Seed sourced from northern populations may not be suitable. Photo credit: © 2008 Keir Morse. -

In addition to milkweed, native plants that provide nectar, will also be important to conserving monarchs. For San Diego County, this could include various species of California lilacs (Ceanothus spp.). -

In addition to milkweed, native plants that provide nectar, will also be important to conserving monarchs. For San Diego County, this could also include various species of monkeyflower (Diplacus aurantiacus).

The coastal species, California narrowleaf milkweed (A. fascicularis), occurs across much of the state. It is also fairly easy to find in nurseries seasonally. However, as I started speaking with local nursery owners and managers, I found that the source of their stock is seed from northern California. These plants may not be ideally suited to environmental conditions in coastal southern California. Casual observation indicates that these plants go into dormancy later than expected for the species, often do not flower, and may not persist in the landscape beyond a year or two. Finding specimens grown from a local source is very difficult at this time, although a number of organizations and government agencies have begun to develop programs to change this.

To maximize the benefits of a native plant garden, care should be taken in selecting plant species. While it is encouraging and exciting to see an increase in native plant availability in nurseries, gardeners should look for species that are truly adapted to the local conditions. Precipitation patterns and totals, soils, and temperature ranges are all factors to consider. I have found species in my local nurseries that will not thrive in my garden, but are ideal for one further inland. I have also found species that are far out of their native range and probably will not thrive. Have I tried some of these species anyway? Absolutely, but with mixed success. Why have I tried them? In some cases because it is rare and I want to do my bit to help preserve the species even if it is ex situ, but usually it’s due to plant lust! New plant species are just so cool!

As I learn more about plant-animal interactions and co-dependence, I recognize that creating a thriving local habitat requires me to look for plants that are truly native and would occur naturally in my area. While many pollinators do not limit their foraging to a particular species or even to native plants in general, others visit only a single plant species. For example, many native bees gather pollen from one plant species, and no other pollen will meet their nutritional needs. Even for generalist pollinators, one cannot be certain that plants not native to the local area are meeting their nutritional needs. The same is true for herbivores, such as caterpillars.

Providing the plants species that have coevolved with local pollinators and herbivores best supports maintaining a food web and biodiversity within an area.

In summary, planting a native plant garden is always a worthwhile endeavor, but the best results are achieved when care is taken to select species appropriate for the area.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service with the Xerces Society and other partners is taking a lead in promoting native milkweed plantings to support monarch butterflies. San Diego Zoo Global is working with CPC locally to promote the use of appropriate plants within San Diego County. Currently, Lesley and others at the San Diego Zoo and CPC have presented to the City of Solana Beach’s Climate Action Commission. The commission is seeking ways to maintain healthy habitats in the face of climate change and seeking advice on plantings, including those that would aid monarchs, in their open spaces, medians, and right-a-ways.

In the future, the program may expand to be more active in increasing demand for local milkweed in both local government and among the public as well as work with local nurseries to ensure the plant material is available.

Native Plant Gardens Don’t Need Rare Treasure to Have Real Value

When learning about the plight of native plants – especially rare plants – and the animals and habitats that depend on them, people often want to help. It seems intuitive that simply growing some of the plants in private homes would help. Yet there are reasons that Center for Plant Conservation partners can’t hand out rare plant seed to their garden visitors to ensure continued existence of the species.

First, growing rare plants is not always straightforward. Not all species are suited to garden environments. Even some that may prove to be so in the future are as yet untried and in desperate need of propagation research. Seed may not be readily available, even for the more common species. Increasingly, nurseries and other growers are looking into developing native plant material (seed and potted plants) for gardeners and restoration efforts. But rare plants are seldom seen as economically viable, as their very rarity limits economies of scale. However, a few more aesthetically pleasing rare plants, with true ornamental horticulture potential, can be found.

Even so, the botanical gardens of the CPC network are not likely to give rare plant material to their plant-loving guests, unless the guests are a part of special program. Though the gardens largely serve their local communities, handing out seed or plants to guests from various locales could send species to inappropriate regions. Precious seed may end up in places where it has no chance of growing, let alone thriving. Worse yet, if the plants are well-tended and thrive far from their native home, they may mix with related species and dilute their unique genetic make-up. It’s not unusual for local plants of the same species to have a different genetic makeup, carrying genes for adaptations specific to their corner of the earth. Bringing in new genes with new adaptations may therefore negatively impact a native population. This is also an important consideration for restoration projects, as detailed in the CPC Best Plant Conservation Practices. This is not to say that eager gardeners shouldn’t grow rare plants. They simply need to be careful about the origin of the plants and the location where they plan to care for them.

Eager gardeners certainly should grow more common native plants, again paying attention to origin and local adaptations. Many CPC participating institutions do have plant sales or advice on horticulturally-friendly species to offer those interested in growing native plant gardens. Though still not common, an increasing number of nurseries are providing native plants, too. Growing a native garden can help many plants wildlife in your area, including rare plants. The pollinators of rare plants often need to visit other plants to collect enough pollen to sustain them. Gardening with native plants thus supports the pollinators that in turn support all native plants. And that’s not the only role that native gardens can play.

Plants are an important part of the complicated food webs of nature. Researchers have documented how neighborhoods filled with beautiful exotic trees can leave wildlife without important food sources. Many birds and insects cannot survive on nectar alone. While generalists are happy to eat whatever is available, many species only thrive on the plants they evolved with. For some, survival may totally depend on the availability of a single plant species. In fact, specialized relationships between animals and plants are the norm in nature rather than the exception.

Plants that evolved in tandem with local animals provide for their needs better than the exotics that dominate most urban and suburban landscapes. By growing natives, people can support natural food webs and use their residential landscapes to connect isolated habitat fragments.

Growing rare plant species in residential gardens might not be the answer to saving them. But growing native plants is an incredibly valuable contribution people can make to conservation of plants and animals. The more local the plants are, the more likely you are to succeed, because the plants will be better suited to that environment. An added benefit is that you will be providing food and habitat to native plants and animals.

More Information

Learn more about the benefits of growing local native plants: Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants

Learn more about appropriate plants from your area through your closest CPC Participating Institution, or your state native plant society.

Polly Pierce

Native plant enthusiast only begins to capture the essence of Polly Pierce. Undaunted by hurricanes or climate change, Polly is truly a conservation champion for native plants. In 2018, the Garden of Club of America awarded Polly the Natalie Peters Webster Medal “for sharing her love of native plants, showing us their beauty, encouraging their creative use, and ensuring their continued availability.” Polly was part of the circle of people instrumental in ensuring the early success of the Center for Plant Conservation and dedicated many years to serving on the CPC board. Today, Polly continues to support CPC with her generosity and wisdom.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

When I was a little kid. I guess it was the hurricane that got my attention – my first memory is of the hurricane in 1938. A tree crashed through my grandmother’s garage, and many oak trees had fallen at our home. The next day, I got to run around and explore the tops of the fallen trees, with the bird’s nests and everything in them. I still live in the same house I grew up in, and know the remaining pines and oaks very well.

My dad liked to garden, and my grandmother across the pond from us liked to have a garden. Her gardener was a jolly Irishman with four girls of his own – and he put me to work, no problem. I was 5, maybe 7. I’ve been surrounded by beautiful gardens all my life.

When I was married, I took a gardening class from Lucien “Kitty” Taylor (also a former New England Wild Flower Society president) through the Massachusetts Horticultural Society. Our last class was a field trip to the Garden in the Woods, and it was like going to heaven. I don’t know if it hooked others, but she certainly hooked me.

You have been involved with several conservation and gardening entities. What draws you to a nonprofit (as a member, donor, trustee, or any other capacity)?

I have always been, and continue to be, a very active person. I’ve been blessed enough to not have to work, and in my era women didn’t have the same opportunities and access to the same jobs. But I wanted to be involved, volunteer. Instead of sewing clothes or doing dinners as a volunteer, I turned to my interests. I loved plants. So gardening and conservation work made perfect sense.

The same goes for my donations and other types of volunteering. I wanted to fill a societal need – and CPC certainly needed resources! Though I still gave and still give to what others may call “normal” repositories for donations, such as hospitals and the like – – gardens, native plants, and education for these activities are my interests and what I give to more often.

In your experience, what are the benefits of gardening?

Joy. You get to see and experience what is there in the garden. I love learning about native plants, and through gardening I can see them up close. We all love the spectacle of a garden, but there is something special about a native wildflower garden – you see what belongs there, what the Lord put there. Gardening, especially native plant gardening, teaches you about where you are. You learn about the soil, light through changes in the year, temperature, and all that. You gain a sense of place.

Why do you believe it’s important to plant and protect native species?

They will vanish if we don’t. In horticulture, we may breed different varieties, but you have to keep the originals! We need to carry this over to nature as well. No extinction! Keep the originals.

Climate is changing. In living in one place my whole life, I see that climate has changed. Plant ranges are expanding northward – trillium did not occur in New England forests 50 years ago, and now it’s considered a native plant. The pond behind my house no longer freezes enough for me to ice skate. Summer birds can be seen here in winter. The threats are real and we need to do what we can.

What advice do you have for a gardener just dipping their toes into native plant gardening?

Attend to the soil! Study the plants and find out what soil they want, what exposure they want, and give it to them. NEWFS [now the Native Plant Trust] makes that easy for people. They provide resources, courses, and an outstanding garden showcasing native plants. It is very instructive to see what should be growing in your area in such a beautiful setting.

Can you share a story about your biggest challenge or most rewarding experience in working with and for native plants?

When CPC was being founded, I was president of NEWFS and was brought in because I knew Peter Ashton at Arnold Arboretum, who then introduced me to Peter Raven. I accompanied Peter Raven to talk to people at the Smithsonian about the budding idea for CPC to get their collaboration and support. Peter,who is a force and very persuasive, talked to them for half an hour solid or so, and they were on board. It was a new concept to me that people in authority, like those at the Smithsonian, really cared. That was very gratifying.

One little triumph was the work with Potentilla robbinsiana (Robbins’ cinquefoil). In supporting NEWFS, and Bill Brumback’s work, it was a true triumph in which Dan (my husband) and I had a hand. Bill was working with the seed from the one known population a mountain top and trying to get it to grow to help conserve it. Meanwhile, the one population was in the middle of the Appalachian Trail and threatened by trampling. We happened to know the president of the Appalachian Mountain Club and talked to him about moving the trail. Bill was able to germinate the seed at high altitudes, bring it down to nurseries and grow it very well. Eventually there was material for reintroductions. There are now four populations on different mountain tops and it was delisted from the endangered species list.

As an original CPC board member, what would you hope for the future of the organization?

Do what you’re doing. But better and more of it. Especially in the face of climate change, and the idea of what is native to where will be changing as the plants travel, we need to bring in more partners. Try to gather the Canadian and Mexican entities to do more for the plants of North America.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Beauty and the Beast: California wildflowers and climate change | A new book by CNPS Press and Winter-Badger Press

Climate change and other human impacts on the environment are threatening wildflowers and the life that depends on them. In this special and timely work, conservation photographers Nita Winter and Rob Badger give us a spectacular view of California’s extraordinary wildflowers as both a cause for celebration and protection.

Read more

Order the book

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today