CPC Best Plant Conservation Practices

to Support Species Survival in the Wild

to Support Species Survival in the Wild

The primary purpose of a conservation collection is to support species’ survival and reduce the extinction risk of globally and/or regionally rare species. A conservation collection is an ex situ (off-site) collection of seeds, plant tissues, or whole plants that has accurate records of provenance, differentiated maternal lines, and diverse genetic representation of a species’ wild populations. To be most useful for species survival in the wild, a conservation collection should have depth, meaning that it contains seeds, tissues, or whole plants of at least 50 unrelated mother plants from each population, and breadth, meaning that it consists of accessions from multiple populations across the range of the species. Conservation collections of seeds should have initial germination and viability testing, developed cultivation protocols, and periodic long-term viability testing.

Questions to Ask Before Acquiring a Conservation Collection

Questions to Ask Before Acquiring a Conservation Collection

Questions to Ask To Determine the Most Efficient Way to Preserve the Plant Tissue Long-Term

Questions to Ask To Determine the Most Efficient Way to Preserve the Plant Tissue Long-Term

How many plant seeds should I collect in a year?

CPC recommends collecting no more than 10% of an individual or population seed production in one season.

CPC recommends collecting no more than 10% of an individual or population seed production in one season and no more than 10 out of 90 years.

The research that supports this recommendation is derived from Menges et al. (2004). Note that it is important to know some aspects of the species population demography, life history, and the initial population size to determine whether your population could be impacted by harvesting 10% of its seed crop in multiple years. If you have enough data, it is possible to generate models to examine the sensitivity of population growth to reduction in fecundity caused by seed harvest. In the absence of this data, realize that generally a population with fewer than 50 individuals will have a higher extinction risk than larger populations. Species that depend on annual fecundity would be most sensitive to harvest. These would be short-lived species (especially annuals) that don’t store seeds in a persistent seed bank (Figure 1.1).

Menges et al. (2004) used theoretical modeling in which they categorized 22 species (25 populations with published demographic data) into three types: Extinction Prone, Sensitive I (high initial extinction risk), Sensitive II (low initial extinction risk), and Insensitive. Insensitive species, nine species with populations with 50 or more individuals, could withstand any intensity of harvest over 100 years and had no extinction risk. The insensitive species they modeled were: Ardisia escallonioides, Calochortus obispoensis, Erythronium elegans, Neodypsis decaryi, Pedicularis furbishiae at Hamlin, Primula vulgaris, Themeda triandra, and Thrinax radiata. Note that these species are trees, shrubs, and iteroparous herbaceous perennials. Species categorized as extinction prone had 100% extinction probability with or without seed harvests. They included: Arabis fecunda, Ariseaema triphyllum, Eupatorium perfoliatum, and Pedicularis furbishiae at St. Francis. The Sensitive I species (Danthonia sericea and Eupatorium resinosum) were iteroparous herbs with clonal growth that had high extinction risk >40% without seed harvest and increased extinction risk with seed harvest above 10% in 50% of the years, while Sensitive II species (Arabis fecunda, Astragalus scaphoides, Calathea ovandensis, Dipsacus sylvestris, Fumana procumbens, Heteropogon contortus, Horkelia congesta, Pana quinquefolium, Pedicularis furbishiae, and Silene regia) had initially low extinction risk that increased with seed harvest frequency and intensity at levels above 10% harvest in over 10% of years. Frequent low-intensity harvests produced models with lower extinction risk than infrequent high-intensity harvests.

After a successful seed collection, it is important to document the collection. Below are some guidelines of how to appropriately document the seed collection:

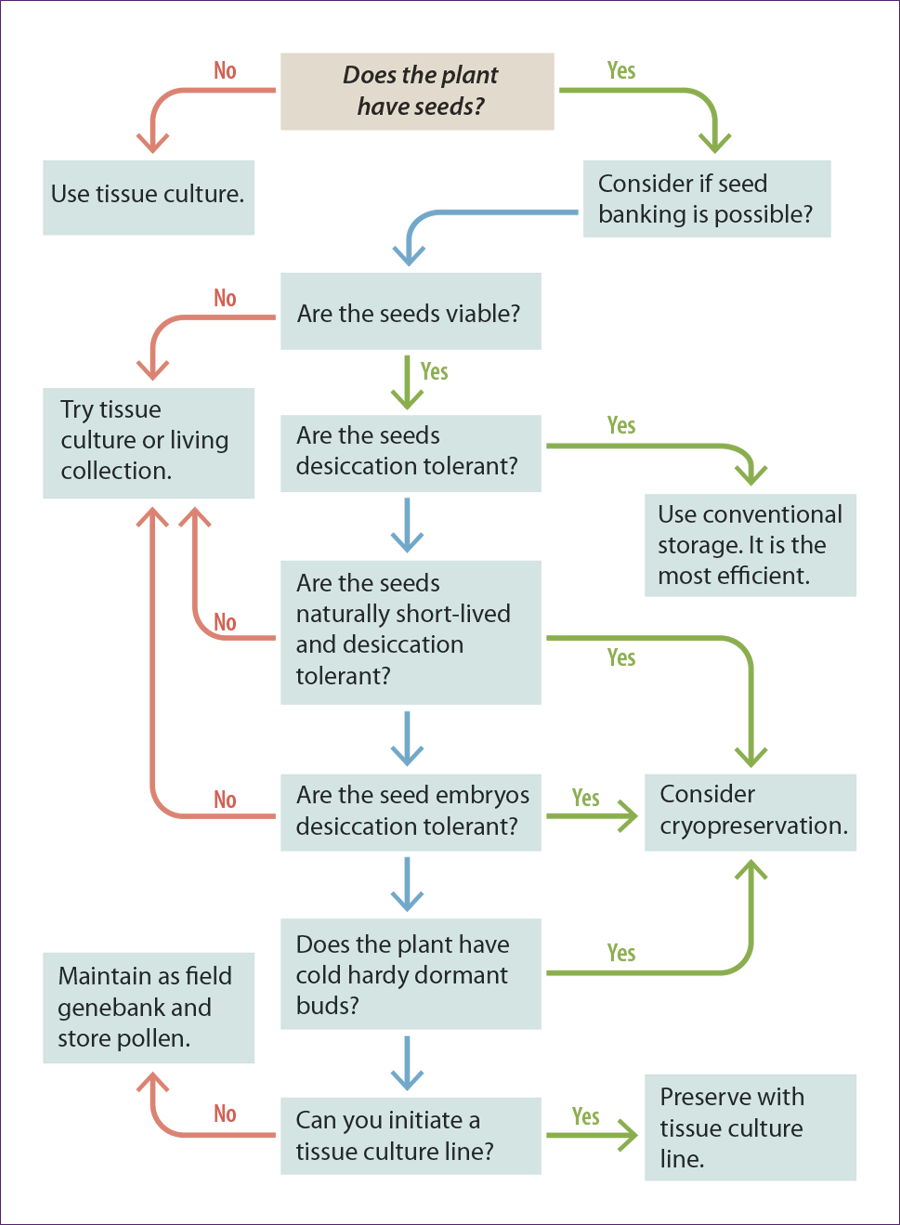

Several authors have examined patterns in seed storage behavior (see references) that can help collectors. Begin with a literature review to check if any previous research has been done on your taxon. You can check congeners, but beware that this is not always reliable or conclusive. Our Hawaiian colleagues have found quite varying storage behavior within a single genus (Walters, Weisenberger and Clark, personal communications). Many factors determine variation in seed tolerance to desiccation or freezing. The following are some general patterns observed in seeds that tend to withstand orthodox storage or not.

| Trait | Likely to Be Orthodox (Desiccation and Freezing Tolerant) |

Questionable Tolerance to Orthodox Storage |

|---|---|---|

| Habitat | Arid is especially likely; If it is not growing in a wetland, it is likely | Wetland, riparian |

| Conditions in nature | Seeds normally experience dry down and/or hard freezes | Seeds normally remain moist and do not experience hard freezes |

| Season of seed production | Not spring | Spring |

| Life form | Not tree | tree |

| Seed bank | Persistent | Not persistent |

| Dormancy | With dormancy | No dormancy |

| Seed moisture content at time of maturation | Dry when it is naturally shed from plant | High (30%–70%) |

| Seed size | Very large (avocado seeds aren't desiccation tolerant) or very small (orchid seeds and fern spores require storage in liquid nitrogen) |

| Plant Groups with High Proportion of Desiccation Sensitive Seeds | Plant Groups with Predominantly Orthodox Seeds |

|---|---|

| ANITAGrade Arecales Ericales Fagales Icacinales Laurales Magnoliales Malpighiales Myrtales Orchidaceae Oxalidales Santalales Salicaceae Sapindale | Solanaceae Poaceae Asteraceae Brassicaceae |

Equipment List

Equipment List

Baskin, C. M., and J. M. Baskin. 2014. Seeds: ecology, biogeography, and evolution of dormancy and germination. 2nd ed. Academic Press, San Diego.

Brown, A. D. H., and D. R. Marshall. 1995. A basic sampling strategy: theory and practice. Collecting plant genetic diversity: technical guidelines. CABI, Wallingford, UK: 75–91.

Bureau of Land Management. 2016. Technical protocol for the collection, study, and conservation of seeds from native plant species for Seeds of Success.

Falk, D. A., and K. E. Holsinger. 1991. Genetics and conservation of rare plants. New York, Oxford University Press.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2014. Genebank standards for plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. Rome, Italy. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3704e.pdf.

Gordon, D., and C. Gantz. 2008. Screening new plant introductions for potential invasiveness: a test of impacts for the United States. Conservation Letters 1:227–235.

Gordon, D. R., D. A. Onderdonk, A. M. Fox, and R. K. Stocker. 2008a. Consistent accuracy of the Australian weed risk assessment system across varied geographies. Diversity and Distribution 14:234–242.

Gordon, D. R, D. A. Onderdonk, A. M. Fox, R. K. Stocker, and C. Gantz. 2008b. Predicting invasive plants in Florida using the Australian weed risk assessment. Invasive Plant Science and Management 1:176–195.

Griffth, M.P., M. Calonje, A. W. Meerow, F. Tut, A.T. Kramer, A. Hird, T.M. Magellan, and C.E. Husby. 2015. Can a botanic garden cycad collection capture the genetic diversity in awild population. Int. J. Plant Science 176: 1-10.

Guerrant, E. O., Jr., and P. L. Fiedler. 2004. Accounting for sample decline during ex situ storage and reintroduction. Pages 365–385 in E. O. Guerrant, Jr., K. Havens, and M. Maunder, editors. Ex situ plant conservation: supporting species survival in the wild. Island Press, Washington, DC.

Guerrant, E. O., Jr., K. Havens, and M. Maunder, editors. 2004. Ex situ plant conservation: supporting species survival in the wild. Island Press, Washington, DC.

Millennium Seed Bank Partnership (MSB). 2015. Seed conservation standards for “MSB Partnership Collections.” Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK.

Reichard, S., H. Liu, and C. Husby. 2012. Is managed relocation of rare plants another pathway for biological invasions? In J. Maschinski and K. E. Haskins, editors. Plant reintroduction in a changing climate: promises and perils. Island Press, Washington, DC.

Seed Conservation Hub. Accessed August 3, 2017..

Volk, G. M., D. R. Lockwood, and C. M. Richards. 2007. Wild plant sampling strategies: the roles of ecology and evolution. In Plant breeding reviews, volume 29. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, New York.

Wieland, G. D. 1995. Guidelines for the management of orthodox seeds. Center for Plant Conservation, St. Louis.

Wyse, S. V., and J. B. Dickie. 2016. Predicting the global incidence of seed desiccation sensitivity. Journal of Ecology. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12725.