Save Plants

Center for Plant Conservation

Message from the President

Systematics includes taxonomy – the naming and categorization of species, as well as elements of genetics, anatomy, ecology and behavior – all used to understand and classify the origins and diversification of life, including plants.

Historically, systematics focused on physical attributes of species. Characters such as shape, structure, size and color were all used to best approximate how species were related to one another. Today we still use these widely informative methods but also extensively use molecular methods – DNA – to ascertain relationships. Combined with advanced computational methods to reconstruct evolutionary histories, we now have the best ever picture of how, when and why life evolved on planet Earth.

What systematics means for conservation is multifaceted but simply put, it helps us to know what species, populations and individuals need to be saved. As important, systematics helps us separate these imperiled species from the more common ones. CPC conservationists are on the cutting edge of using systematics to help ensure we know and save all of the remarkable plants out there. Please read on to learn more about systematics and what it means to classify and then act on that knowledge to Save Plants.

Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden

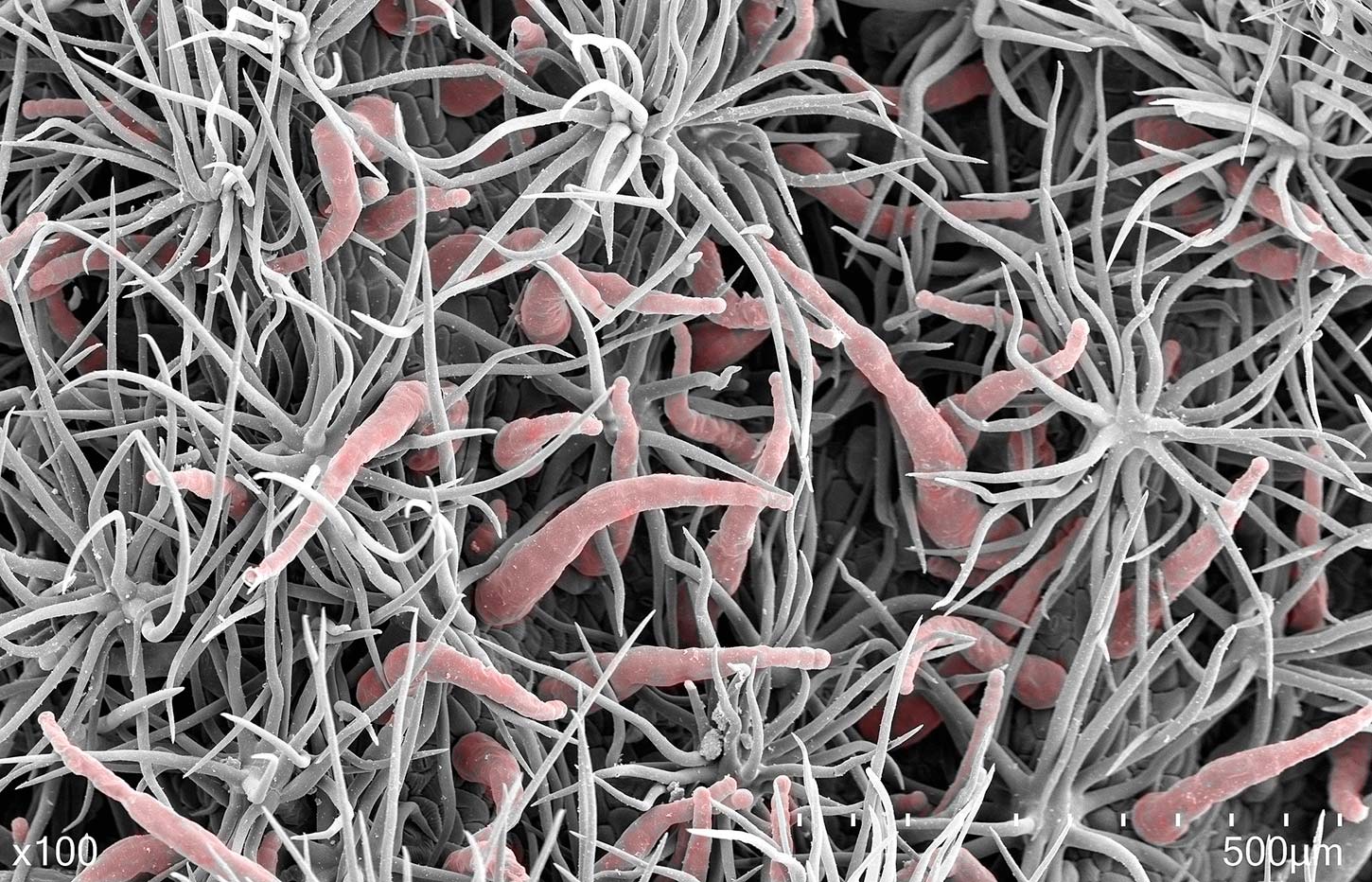

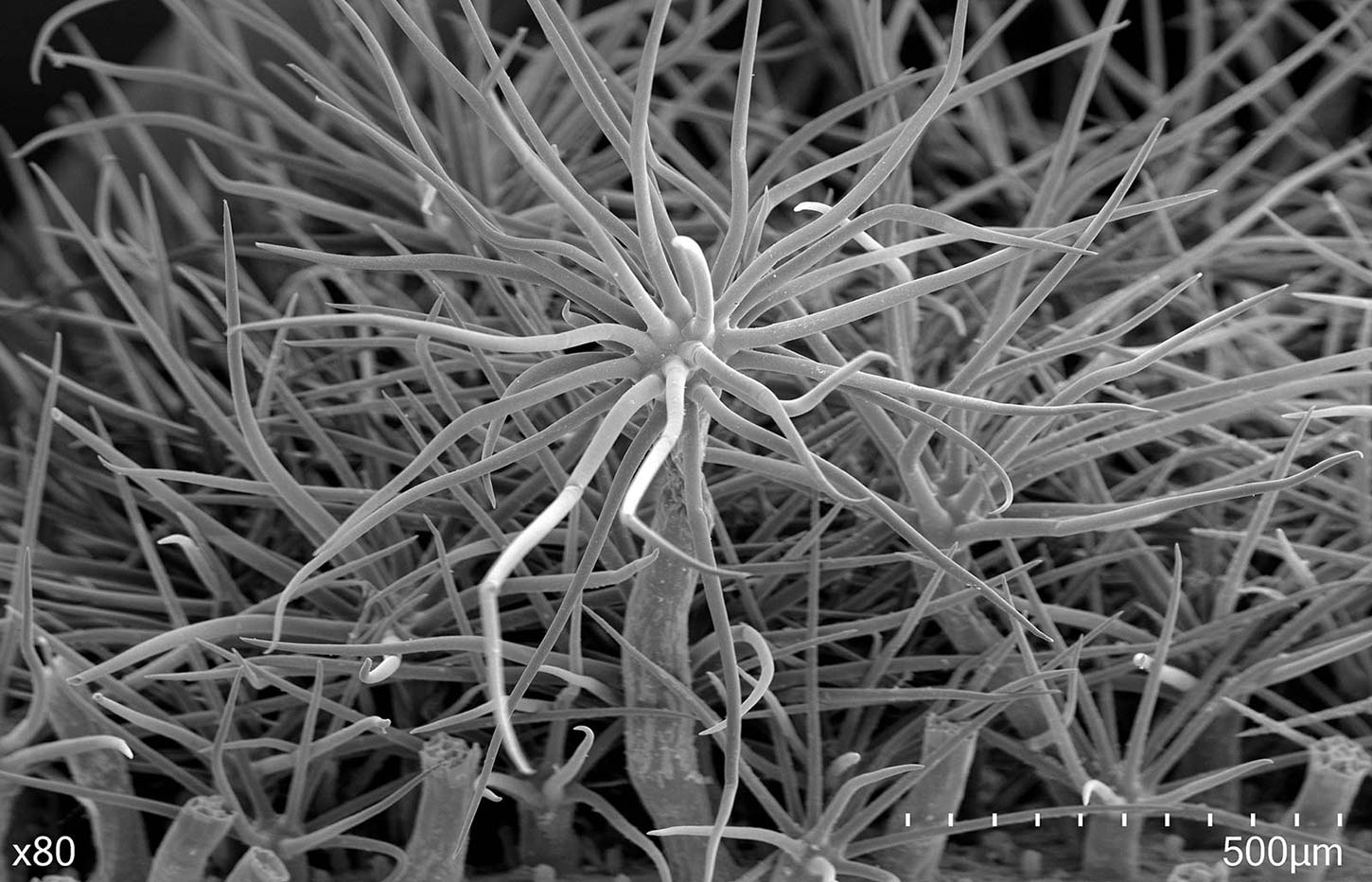

Heller’s bush mallow (Malacothamnus helleri), a rare species currently lumped in the more common Fremont’s bush mallow (M. fremontii). Keir’s research will help determine if M. helleri should be recognized as a separate taxon and thus retain its rare status or if it is just a minor variant of M. fremontii not distinct enough to warrant conservation status.

Coming across a set of beautiful pink to white globe-shaped flowers on a shrub with delicate star-shaped hairs on its leaves while hiking in San Diego might grab your attention. If you’re a botanist, you might be inclined to figure out what it was. You may recognize it as being in the mallow family (Malvaceae), or even as in the genus of bush mallows (Malacothamnus), but as you worked through your taxonomic key, you might run into some trouble. Field botanists quickly become familiar with taxonomic keys, working through the series of choices is the key to help them identify an unknown plant they have come across. These keys are important tools for conducting vegetation surveys, botanical surveys, and more but they can also have problems. Problems often stem from different approaches and results in the study of a group’s systematics (the classification and study of evolutionary relationships among species). Such was the case with keying out the Malacothamnus aboriginum found in San Diego County.

A seasoned field botanist, Keir Morse, was very aware of the keying difficulties with bush mallows in general and the taxonomic treatments, delineations, and descriptions of species. So, with the prompting and help of another San Diego area botanist, Tom Chester, Keir decided to look into the issue with M. aboriginum. The San Diego County populations were highly disjunct (not connected) to the more northern populations and had not been included in the previous studies of bush mallow morphology (physical features) that helped define the species. Conducting their own morphological study, looking at physical characteristics that are commonly measured, as well as new characteristics, they determined the San Diego populations to be their own species.

Keir knew there were issues throughout the genus: there are currently three different treatments of the genus in use, which conflict with each other. Emboldened by the success of the M. aboriginum work, he became interested in resolving the issues throughout the genus. To do so, he would need to learn more about how the lines between taxa (species and infraspecies, such as subspecies and varieties) are drawn and what information is needed to draw those lines – that is learn more about research in systematics. Working towards a doctoral degree at a place well known for their focus on systematics and floristics seemed like the next step and he soon found himself enrolled in the graduate program at Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden (RSABG) through Claremont Graduate University.

As he started this program, Keir quickly defined his project: to resolve the taxonomy of the genus, with an emphasis on the conservation questions. Systematic research is very important to conservation because deciding where species lines occur affects how rare those species are considered. The oldest bush mallow treatment to examine all named taxa recognizes 28 taxa in total, while the other more recent treatments recognize 11 or 17. Largely using the older treatment, the California Native Plant Society, through their Rare Plant Ranking system, recognizes 16 as rare. If some of these rare taxa are found to be just minor variations in highly variable taxa, then perhaps they should be lumped into these more common taxa and be delisted. This would allow any rare conservation resources going towards those species to be used on taxa more in need. Likewise, if some of the rare taxa lumped in the more recent treatments should be recognized, a new treatment needs to be put forth to easily identify what is rare and what is not. Better defined species lines that are easy to key out, are also helpful in determining what seed stock is appropriate to use for restoration or even landscaping. Using seed of a species from a different region could introduce hybridization problems. Tackling the species history and systematics is not just a botanical curiosity, there are conservation concerns tied to these results.

Keir is taking a total evidence approach to resolve the various issues within this complicated group of species. This means he’s not relying solely on morphological analyses, nor any other single type of data or analysis to make conclusions about taxon borders. Instead he is using a combination of morphology, genetic analyses, flowering time (a possible reproductive barrier), and extensive field evaluations to look at the larger picture.

Collecting all the data has presented its own challenges. All the field experience and time in the world does not help you find a species that simply is not showing up: many of these plants are fire followers (only germinating after fires) and then only live for a few years (3-20) before being outcompeted by returning vegetation. So it has been challenging to find plants in areas that have not burned. Here, the extensive resources of RSABG and other botanical institutions have been an enormous help to Keir. Herbarium specimens (many over 100 years old) can be used to measure some of the morphological characteristics of those populations that are now only dormant in a seedbank awaiting a fire or otherwise inaccessible. Though herbarium specimens can be used to provide DNA samples, the extractions can be difficult due to the degradation of the DNA. Fortunately, some of the herbarium specimens have seed which can be grown to new plants for high quality DNA extraction or seed is available in the long-term seed bank.

Also, aiding Keir in data collection is the online citizen scientist platform, iNaturalist. The pool of scientists and hobby naturalists across the range of the genus throughout California (and bits of Arizona and Baja Mexico) has helped Keir move past the difficulty of making multiple visits to all field sites to capture phenology. Over 1,000 people have contributed to his project, making over 2,700 separate observations. With thousands of observations, many locations have been found allowing for fresh specimen (including DNA) collection and more data to be taken.

Results thus far are pretty preliminary but also pretty promising. Keir’s keen observation skills helped him define a new characteristic for the genus, the fact that the flowers of M. fremontii dry open while other species dry closed, which has proven useful in distinguishing two similarly looking and occasionally lumped species that are also supported as different through genetic analyses. That the two methods support each other is encouraging. And so Keir continues mining iNaturalist (you can contribute, too!), spending hours in the herbarium or in the lab, and days in the field. He is confident that a clearer picture of this interesting group of mallows is forthcoming.

All photos Courtesy of Keir Morse, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden

Banking Biodiversity

Based on an interview with Morgan Gostel, Ph.D., Director of GGI-Gardens, Research Botanist at BRIT (brit.org)

It’s hard not to sound alarmist when we realize the urgency of the threat of species extinction: we are at risk of losing species before we are able to identify and understand them. Fortunately, there are people working to understand these species before they are lost – increasingly through genetic and genomic approaches – and documenting diversity is often the first step to conserving it. Genetic techniques are becoming more common and accessible, with costs having dropped such that it is no longer the prohibiting factor in research – obtaining tissue samples is. The need for genome-quality tissue samples combined with threats to species diversity has pushed the scientific community to coordinate and proactively preserve the world’s diversity.

The Global Genome Initiative (GGI) was founded with this goal at heart – to capture half of the world’s genomic diversity – that is collect samples from half the genera on earth – by 2022. Based at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, GGI has grown into an international program that facilitates collections-based research. As Director of GGI, Dr. Jonathan Coddington, will tell anyone that part of what drives GGI is awareness that the fundamental limiting factor for biodiversity genomics is no longer the cost of sequencing genomes, but access to genome-quality tissues. Since GGI was founded, Senior Research Botanist and Curator, Dr. Vicki Funk recognized its importance, but also saw the need to collaborate with botanical institutions around the world. Vicki imagined two things for how the botanical community could rally behind GGI’s mission: 1) forge closer bonds between botanic gardens and the herbarium community – two communities that are on the front lines of plant conservation and research; and 2) she made a bet (for a fine bottle of wine, no less) that half of the genera of plants on Earth could be found living in gardens around the world. That bet paid off big time and in 2015 GGI established the Global Genome Initiative for Gardens.

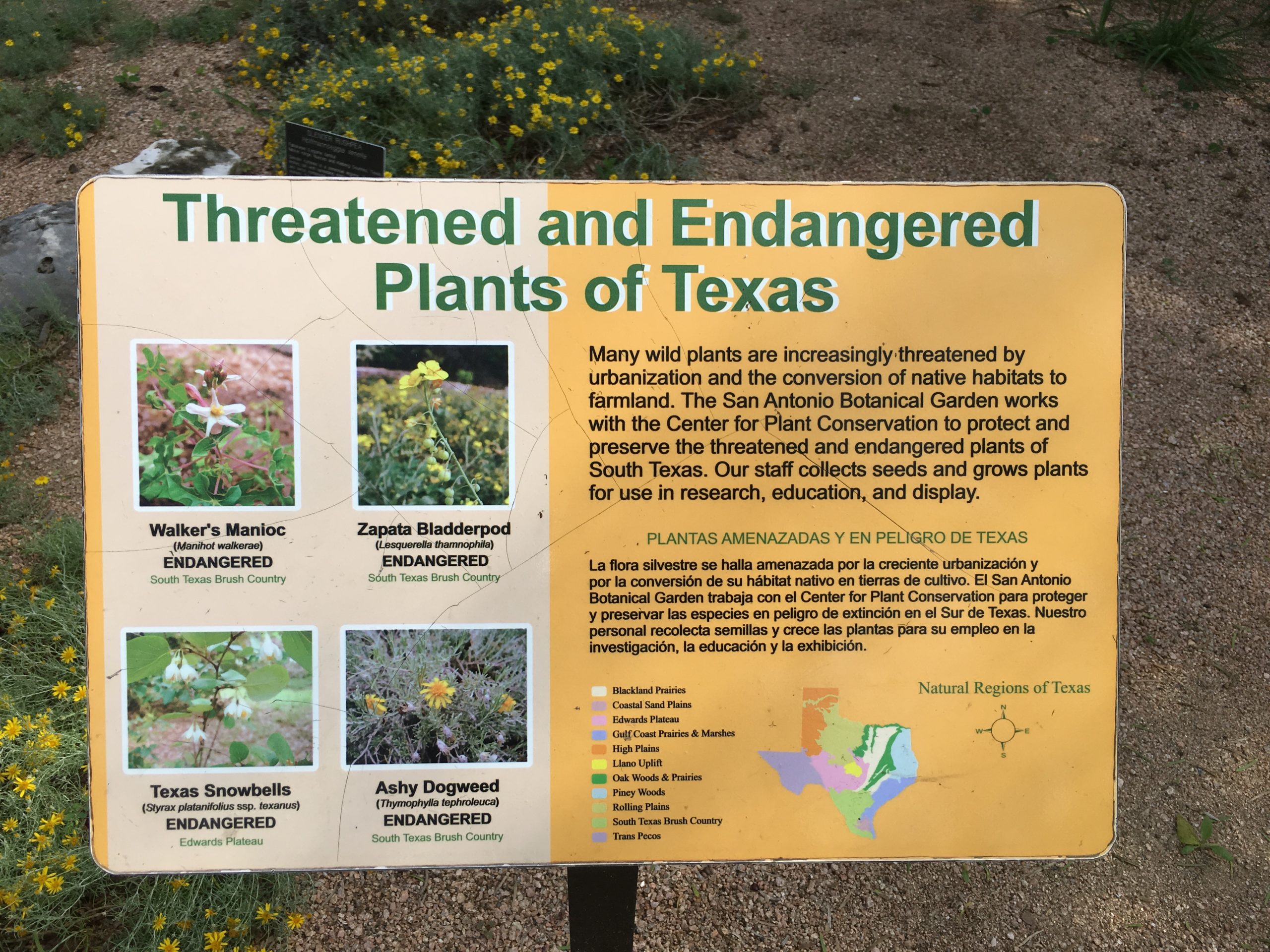

With GGI’s support, GGI-Gardens has been working to increase the amount of botanical biodiversity represented in biorepositories and available for research since 2015. In this way a major outcome for GGI-Gardens is to increase the impact and visibility of gardens in botanical research. Dr. Morgan Gostel was brought in as Program Manager for GGI-Gardens in 2015 to coordinate the program’s efforts and last year, GGI-Gardens moved with Morgan to the Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT) in Fort Worth, TX. With research interests in evolution and systematics, Morgan is keenly aware of the central role botanical gardens play in collections-based research, the importance of collecting a broad array of genetic material, and making tissues more available for research and conservation. Botanical gardens have been at the center of Morgan’s research on the evolution of species diversity occurring from Madagascar to Brazil. Throughout his career, gardens have facilitated Morgan’s research – from the Cullman Program for Molecular Systematics at New York Botanical Garden, to the Missouri Botanical Garden’s Africa and Madagascar Program, and his new home in Fort Worth, TX at the Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT) where he is working across the state to partner with and build capacity for botanic gardens in Texas.

The GGI-Gardens ethos is rooted in understanding resource limitations – particularly at institutions such as gardens and stresses a partnership approach focused on synergism rather than novelty. For instance, in addition to their diverse living collection Denver Botanic Gardens has an active seed banking program that focuses on the collection and preservation of rare, Alpine flora throughout Colorado. It was easy to identify synergies between GGI-Gardens goals and what the garden was already doing on rare and threatened alpine plants. The team was already out collecting seed for seed banking and material for the living collections. After partnering with GGI-Gardens, collecting genetic samples on silica is a regular part of the field protocol.

Helping bridge ties between research and horticulture departments is also key. Morgan cites an example of a garden that maintained an impressively diverse Compositae (sunflower family) bed in the garden for years. A researcher, thinking of the easy access to genetic material from this garden, sought samples only to learn that the bed had recently been replaced – and that herbarium vouchers had not been taken, let alone genetic samples. It is particularly concerning when one considers a high percentage of the plants brought into botanical gardens are lost within one year of their arrival. This diversity can still be useful to science if captured in voucher specimens and/or genetic samples. Working with gardens to better connect research and horticulture programs and to catalogue the diversity they already collect, will benefit more than just their institution.

Making the material available for researchers is another large part of the project. GGI was instrumental in the establishment of the Global Genome Biodiversity Network (GGBN), a worldwide community of biorepositories whose mission is, among others, to develop and ensure best practices for tissue storage and facilitate accessibility to biodiversity tissues for basic research. GGBN partners don’t just store tissues, they facilitate genome sequencing, data accessibility, and ensure material is accessed and utilized in accordance with national and international policies. They also work to connect botanical gardens to researchers, ensuring that the botanical gardens are acknowledged for their contribution.

All bets aside, Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) helped facilitate an assessment of garden inventories in 2017 that confirmed that over 50% of vascular plant genera are kept in botanical gardens. But perhaps more importantly, the assessment lays out a road map for identifying gaps and priorities, where the conservation community might focus efforts to document, preserve, and conserve at risk and vulnerable flora. Much of this is outside of the United States and so the Global component of GGI is essential. GGI-Gardens has recently partnered with the Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro to increase representation of the unique Brazilian flora. An estimated 25% of the worlds plant species occur in Brazil and their push to collect the native flora is important not just for this institution, their students, and researchers, but for scientists more broadly.

What GGI-Gardens is working towards is creating a collection that complements herbaria and seed banks with genomic tissues that will provide instrumental resources for botanical research in the 21st Century. Like all natural history collections, the tissue samples being collected have untapped, perhaps limitless potential. There are secrets hidden in plant DNA that can change the world; building collections that facilitate genome sequencing will lead to discoveries that help us better conserve and understand Earth’s remarkable biodiversity, and open doors for the future.

Read more on Nature.com: Ex situ conservation of plant diversity in the world’s botanic gardens.

Plant Genetics Workshop – Wielding a Powerful Tool

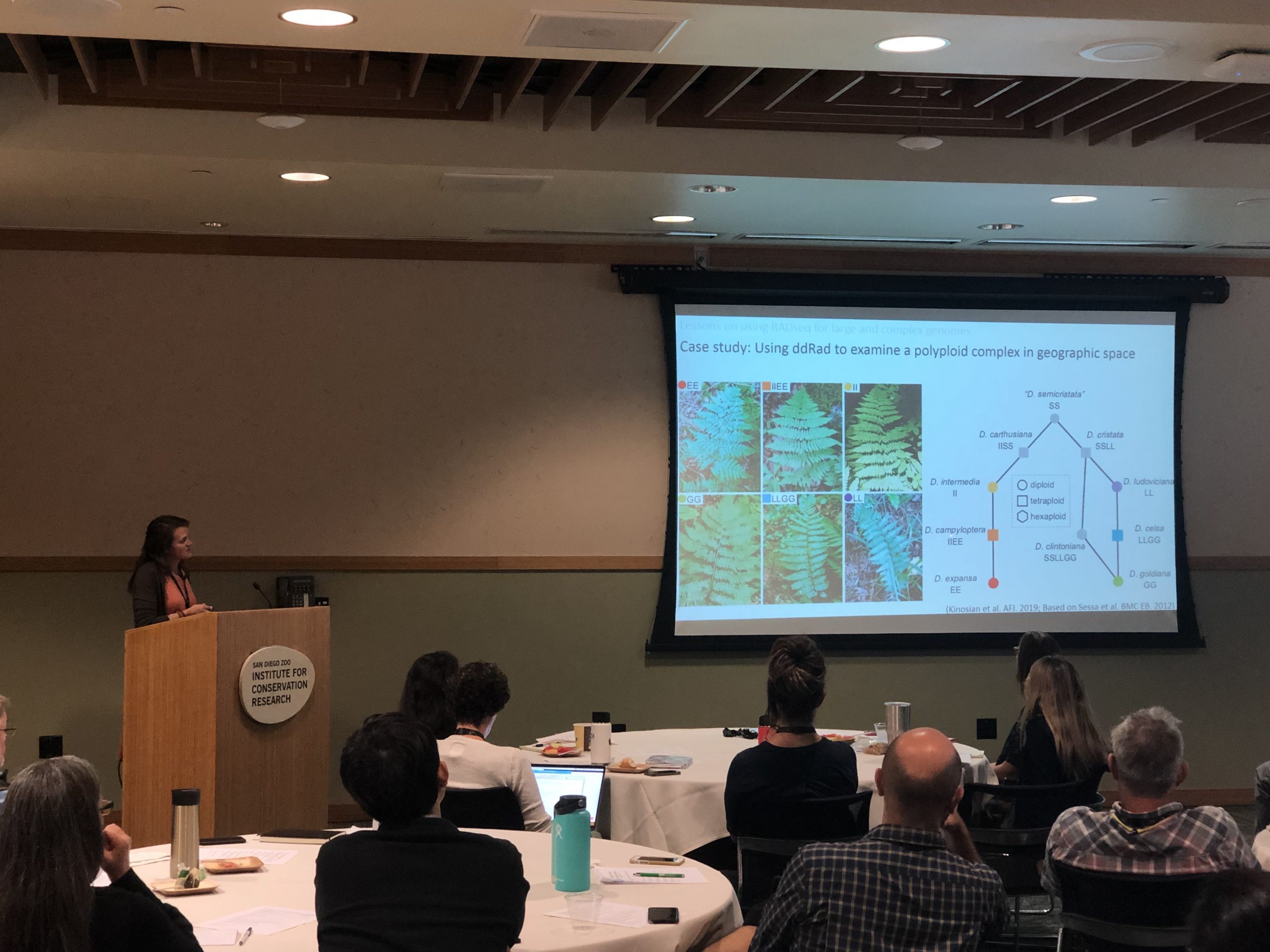

In the field of systematics, genetic analyses have become a powerful tool to help understand where to appropriately draw lines between species, how genes flow between populations or even species, and how different taxa are related. Last month, San Diego Zoo Global brought together a variety of researchers for a two-day Plant Conservation Genetics Workshop.

In the field of systematics, genetic analyses have become a powerful tool to help understand where to appropriately draw lines between species, how genes flow between populations or even species, and how different taxa are related. Last month, San Diego Zoo Global brought together a variety of researchers for a two-day Plant Conservation Genetics Workshop. The workshop attendees addressed many issues associated and provided many experiences, though there was a focus on methodologies, particularly related to restriction site associated DNA sequencing (RAD-seq), which is a method that can provide comparisons of up to thousands of points within a long sequence of DNA. Many CPC Participating Institutions participated in the workshop, sharing their experiences using genetic techniques to better understand species relationships.

Sally Chambers, Ph.D., of Marie Selby Botanical Gardens presented her work using double-digest RAD-seq (using two enzymes to digest DNA rather than one, allowing for more control of digestion sites) in her attempt to resolve relationships within a group of North American ferns. The technique has its limits with large or complex genomes (of which ferns have both), and the project hit some barriers. For instance, some known relationships among hybrids were not appearing in the sequencing data. But in understanding some of the problems with the technique, Sally’s experience can inform others working with species with complex genomes.

From Denver Botanic Gardens, Jennifer Ramp-Neale, Ph.D., showcased a few of the many conservation projects that the Gardens undertake. Combining genetics work with demographic monitoring, niche modelling, and morphology studies, they were able to learn more about the rare Colorado hookless cactus (Sclerocactus glaucus) – including that it was not significantly hybridizing with its more common, hooked brethren – and allowing them to better refine the geographic boundary. Their integrated approach helps provide a broader context to land managers helping to conserve this species and enforcing policies to protect it.

A prime example of the importance of describing and naming species for conservation, Alex Lignan, Ph.D., from Missouri Botanical Garden shared his work on species of ebony (Diospyros) endemic to Madagascar. Naming a species helps provide legal protections to protect against logging within the group of trees.

Of course, genetic analyses have power beyond informing systematic studies. UC Botanic Garden’s Vanessa Handley, Ph.D., unveiled their plans to conserve the genetic diversity of an important ex situ cycad collection and the genetic research aiding that effort. San Diego Zoo Global’s Stephanie Steele, Ph.D., discussed her efforts to understand the role of genetics in bark beetle and drought resistance in Torrey pines, and the potential management issues the genetic information can provide.

The power of genetics analyses to contribute to systematics as well as issues of management and for genetic rescue is clear. The unique challenges presented by plants, many of which have complex genomes or issues of polyploidy (having more than two paired sets of chromosomes), are still being worked through and are being met head on; and the more we learn about and share the methods, the more powerful the tools will become.

Naomi Fraga, Ph.D.,

A few years ago, Naomi Fraga became Director of Conservation Programs at RSABG, tasked with formally bringing together their well established and diverse plant conservation projects under one umbrella. Having built her career to help conserve the plants she loves, she has thrived in the role, building upon the garden’s rich history of conservation work.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I would like to think that I have always been in love with plants but I distinctly remember the time when my love became undeniable. I was an undergraduate at Cal Poly Pomona and was fortunate to find a volunteer opportunity in the herbarium at Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden (RSABG). My first job was to transcribe label information from specimens into a database. I learned so much about plants working in the collection; they became an inspiration to me and they are now the basis for my life’s work. After that volunteer opportunity, I never looked back. I was not only in love with plants but I was also committed to their conservation.

What was your path to becoming the Director of Conservation Programs?

Once I found the herbarium at RSABG, my path became pretty straight forward. As my love and appreciation for plants grew, I knew I wanted plant conservation to be at the center of my work. I thought in order to conserve plants, I ought to know them well, so I undertook a M.S. degree in Botany. My master’s work set me up to lead the field studies program at RSABG, implementing botanical surveys and rare plant studies. While working in the field studies program, I thought there was more I could do to contribute to plant conservation but I needed more tools in my toolkit. So, with my strong foundation in field botany, I returned to graduate school, this time to earn a Ph.D. in Botany studying systematics of a group of conservation concern, the monkeyflowers (family Phrymaceae).

While I was working on my dissertation, I maintained my full-time position at RSABG. This was very challenging but also very rewarding because as I was growing as a scientist, our conservation program was growing as well. Upon my graduation in 2015, I was ready to move into my new role as Director of Conservation Programs. It was a new position at RSABG, so it allowed me the creativity to bring my vision of conservation of California native plants to the forefront. This was an opportunity for me to bring RSABG’s magnificent resources together in a unified fashion to enable and advance our work of conserving plants. I have been happy in this position ever since, and it is perfect for me.

What about working with plants has surprised you?

What surprises me the most about working with plants is that it is just as much about working with people as it is about working with plants. I oversee a diverse program that includes mentoring staff who are working in the fields of restoration, seed conservation, field botany, conservation genetics, and invasive plant management. The team I work with is incredibly talented and diverse in skills; and I feel fortunate that through them I get to work across these diverse disciplines within plant conservation. I also work in partnership with a diverse set of agencies and organizations to advance the science of plant conservation and to apply the principals of our work on-the-ground to make real tangible change. I enjoy working collaboratively, and if there is anything I have learned about plant conservation, it is that working together in a community (like CPC!) can have a huge effect for good. I have also found that public support and education are central to plant conservation. As such, a significant part of my work more recently has been centered on education and outreach to broader audiences. I hope through this work to guide more people to (re-)discover their love for plants just as I did when I was an undergraduate working in the herbarium.

What has been the most challenging aspect of your work?

By far the most challenging aspect of my work is deciding which projects to focus on and where to devote my time and energy. There is so much good work going on in California and a lot of opportunities to make positive change but we also face a lot of significant conservation challenges. I have learned that I cannot be in three places at one time (although I have tried!) and that prioritization is necessary because we all have limited time and resources.

Why do you believe good systematics research is important for conservation?

My training as a botanist and plant conservationist has been in plant systematics so I hope I do not seem too biased but I do believe that plant systematics is foundational to the science of conservation. Plant systematics is essentially biodiversity science; it enables us to carefully study, document, and increase knowledge about all the parts we are trying to conserve. The Endangered Species Act is a bedrock environmental law that relies on the understanding of diversity, namely species, as a unit of protection. Therefore the description and understanding of species diversity is central to our efforts to conserve them. In all of my diverse work as a conservation scientist, I find that I rely heavily on my training as systematist to inform conservation decisions. My training provides a key perspective on biodiversity that is not always well-represented in the multidisciplinary field of conservation.

What current projects or approaches in plant systematics excite you most?

There are so many exciting developments in the field of plant systematics – it is too difficult to pick just one area. Our ability to understand and document the tree of life will only grow as technology increases. From high through-put sequencing to the pace and scale at which we are able to digitize our collections; it seems like the possibilities are endless. However, as we try to construct the tree of life, there is one motivating factor that is always resident in my mind and it is that extinction is forever. To lose any segment of diversity on the tree of life, no matter how big or small, is tragic. This is what motivates me to increase our understanding of plant diversity on earth. To understand diversity is a mechanism to protect it: after all, we can’t protect what we do not know that exists. With those principles I hope we can empower the next generation of systematists to build on our knowledge of the green tree of life, as this will begin our path forward as we work to protect all life on our planet.

-

Naomi worked with her mentor Steve Boyd at Hidden Lake to conserve Hidden Lake blue curls – a taxa which was recently delisted. -

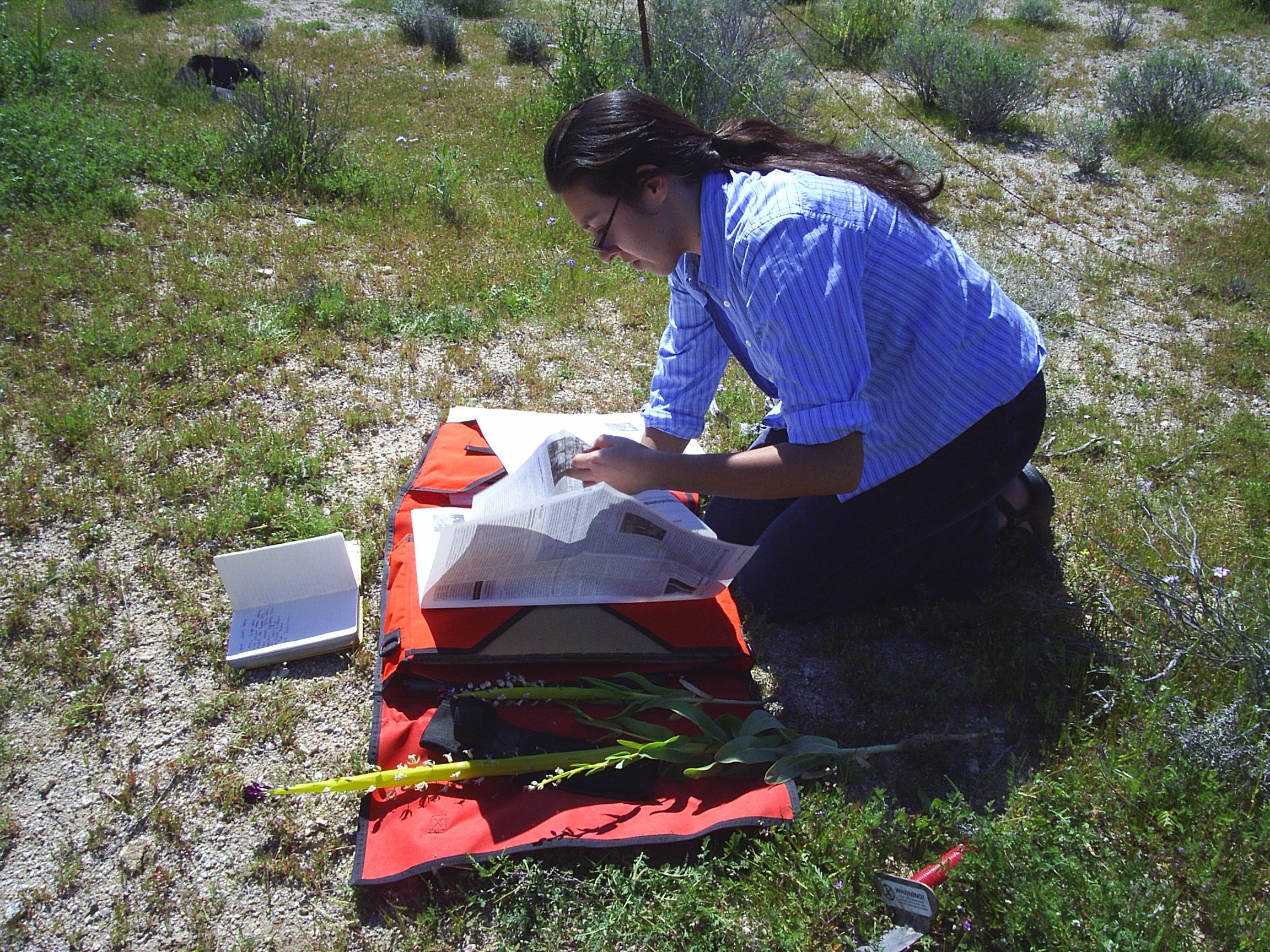

Naomi’s time in the field for her master’s project laid the foundation for her to lead the field studies program at RSABG, in which position she implemented botanical surveys and rare plant studies. -

Long involved in CPC projects, Naomi conducted field surveys with Tasha LaDoux in Joshua Tree National Park in 2006 as part of a larger CPC-National Parks program.

Photos Courtesy of Naomi Fraga, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Employment Opportunities

Red Butte Garden has launched a nationwide search for a new Executive Director (ED) to succeed a seventeen-year incumbent who will be retiring in the Spring of 2020. The new ED will build upon the Garden’s strong foundation to increase the organization’s visibility, extend its educational programs, strengthen its financial resources, update and implement its Master Plan for future growth, and generally continue to expand Red Butte’s local and national influence and recognition.

The ED reports to the Chief of Staff in the Office of the President and works closely with a variety of departments within the University, the Garden’s Advisory Board, and Garden staff to develop and implement the strategic vision, priorities, and policies of the Garden. The ED is directly responsible for the overall management and direction of Red Butte Garden.

VIRPI is a conservation project based at the St. George Village Botanical Garden. In this grant-funded project, rare plants in the Virgin Islands, as well as other areas of the Caribbean region deemed appropriate, will be identified. As much information will be gathered about these species as possible, and propagation material, preferably seed, will be used to grow the plants. Some seed will also be seed banked if feasible. Genetically significant plantings will be maintained at the botanical garden, as well as other locations. Plants will be returned to their native islands for replanting and supplied to other areas for education.

Key Functions of the VIRPI coordinator:

Coordination and facilitation among partners

Prioritize and strategize collection trips

Assist with propagation

Provide label and data administration

Distribute plant material

Develop grant proposals

Network with the conservation and botanical garden communities

Disseminate information through articles, social media, etc

Qualifications:

Management, or related field

Organizational skills required and program development experience

Excellent written and oral communication skills

Proficiency in Microsoft Office suite, social media, web content development, Google applications

Success Factors:

Experience with horticulture, environmental science, botany, natural resources

Strong interest in plants and threatened species

Self-motivated with the ability to collaborate

Understanding of national and international conservation policies

Ability to understand, interpret scientific literature and peer-review articles

Ability to use data bases, spreadsheets, and proficiency with internet research

Attention to detail

Bachelor’s degree

For more information contact Dewey Hollister

News and Events

CNPS Workshops: Mitigation measures & monitoring

California Native Plant Society’s plant science training workshops provide botanists, biologists, ecologists, and others with the scientific skills and practical experience necessary to assess, manage, and protect native plants and lands in California and beyond. Small classes offer hands-on learning from field-leading experts in both the classroom and field.

Details & registration are available now for all 2019 workshops.

MITIGATION MEASURES & MONITORING – taught by David Magney

October 22-24, Sacramento, CA

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today