Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

November 2018 Newsletter

Let’s face it, we live in a technologically-focused world. Most people these days spend more time glued to their smart phones than they do stopping to smell the proverbial roses. While technology has certainly removed us from nature in many ways, it is also critical to the future of saving species on this planet. Today, plant conservationists have embraced technology to Save Plants in ways we never could before. Advances in science, communication and conservation application are all led by our ability to embrace and harness the potential of technology. In this month’s issue of SavePlants, we explore some of these advancements including how we use modern genetics to manage living collections of rare plants, how we communicate conservation needs and values, and how we share cutting edge results on the science of saving plants with other conservationists. By all counts, CPC partners are at the forefront of the interface between technology and plants, and the plants – and our planet – are better for it. Read on to learn how the tree huggers and geeks have come together to Save Plants!

Changing the Approach

Chicago Botanic Garden

Based on contributions from Jeremie Fant, Ph.D.

Growing on a cliff side in Hawaii a lone alula, or cabbage on a stick (Brighamia insignis) is the last natural, wild member of its species. Fortunately, seed from some 15 individuals had been collected decades ago and the species has persisted in ex situ, that is away from its natural environment, in collections at CPC institutions, allowing the species to persist. But that didn’t mean this unique, Hawaiian endemic was in the clear.

Though seeds were collected along maternal lines and the lead institution, National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG), has taken great care to make sure those lines are all represented in each generation they propagate, the main alula collection has shown signs of inbreeding depression (some flower anthers were not developing and hand pollination efforts were not always taking). A genetics study revealed that some of the genetic diversity from the wild had been lost. Preserving the remaining diversity, and maybe even gaining the lost diversity, became a primary goal in maintaining this species. This is where Jeremie Fant, Ph.D., and his molecular ecology lab at Chicago Botanic Garden have been able to help.

Jeremie and his team are drawing on various technologies, from genomics to data sharing, to help take a new approach to maintaining ex situ collections, starting with alula. And the inspiration for the approach came from an unexpected place – the tale of the black-footed ferret.

Once extinct in the wild, U.S. Fish and Wildlife began a breeding program with just 18 ferrets to serve as the founders in the late 1980s. Using assisted reproduction and carefully planned studbooks (a record of pedigrees that informs who should breed with who next) to maintain genetic variability, black-footed ferrets have thrived in captivity and have been successfully reintroduced in the wild. Now there are 18 wild populations, five of them self-sustaining. When Jeremie was thinking about alula and other rare plants with a small number of individuals, he couldn’t help but think of the ferrets and their immense success with such a small number of founders. It dawned on him that careful use of pedigrees could be used to help plant species.

Zoos have been using studbooks for decades to help them maintain ex situ populations and help rare species recover. But the plant world has relied more on maternal lines maintenance – even when hand pollination has been necessary and thus the plant paternity controlled, this hasn’t been recorded. But it could be. And like zoos trading animals or sending sperm to enact the studbooks’ recommendations, botanical gardens could share pollen and help breeding efforts maintain genetic diversity. Having a studbook guide breeding would also help prevent horticultural convenience (i.e., using more seed from the individual that produced the most flowers) from overriding best practices.

The alula was a great species to test this approach on because much of the initial genetics work for the species had been done, its seed can’t be stored, and seed from the initial collection had been shared with other institutions. Finding those institutions was an early step for Jeremie. Though each institution maintains excellent records, the information is not always available to others. He was able to use Botanic Gardens Conservation International’s (BGCI, a CPC partnering institution) database to identify plants which originated from that initial wild-collected seed, held at not just NTBG and Chicago Botanical Garden, but also UC Botanic Garden, San Diego Zoo, and even Switzerland. Data sharing is, and will continue to be an important part of this collaborative project.

Advanced genetic technologies will soon be a part of the effort. Jeremie has been working in the lab building the genomic libraries to look at adaptive traits. Many years ago a genetic study using microsatellite markers was conducted with Kayri Havens, Ph.D., at Chicago Botanic Gardens. These techniques focused on neutral traits (those that may or may not be used by the plant) and helped guide the initial studbook and pollen trades. But Jeremie hopes to use more genomic analyses to make sure they are conserving adaptive genes – the parts of the alula’s genome actually being expressed by the plant.

Advancing technologies mean a lot of genetic information can be collected, but how to incorporate that into studbooks, or population management in general, will need to be worked out. Moving forward it would be ideal for the genetic information and breeding history of the plants at each location to be in one place, to better inform the studbook. Sharing more data and information in accessible databases will be key in helping expand this work.

Technology has opened many doors, but how to best use these new tools and information is often another step. Thus far, the studbook approach is getting good results. The alula at several of the BGCI located institutions have genes no longer being carried in the main NGBT population; these gardens have been sharing their pollen and improving breeding output. With such a promising start Jeremie is hoping the studbook approach can help other rare species. He doesn’t have to look far – one third of the relatives of alula known as the Hawaiian lobelioids, have under 50 individuals and unbankable seed. Hopefully studbooks can be used to save more plants and, like the black-footed ferret, become a conservation success story.

Maternal Lines

Plants are, as a rule, promiscuous individuals. Pollen is released in the air or hitches a ride on a pollinator with the hopes of landing on the same species and developing seed. Thus we can’t be sure of paternity (i.e., which plant was the pollen donor) without genetic analyses. Flowers on the same individual, even the same cluster of flowers on that individual could have very different pollen sources, but they will all have the same mother – be from the same maternal line. Tracking maternal lines helps track genetic diversity in ex situ collections.

-

Chicago Botanic Garden cares for several alula plants, descendent from the original wild collected seed as the main ex situ population at National Tropical Botanic Gardens (NTBG). And they aren’t the only ones, with individuals at San Diego Zoo, UC Botanic Garden, and more. Some of these collections have the genetic diversity that has disappeared from NTBG’s population and will be key to interbreeding using the studbook approach. -

B.insignis flowers -

B.insignis outplanted at Makauwahi cave Gardens have been working to save this species for sometime, propagating plants to maintain diversity as well as for outplantings to ensure this special Hawaiian endemic stays in the landscape.

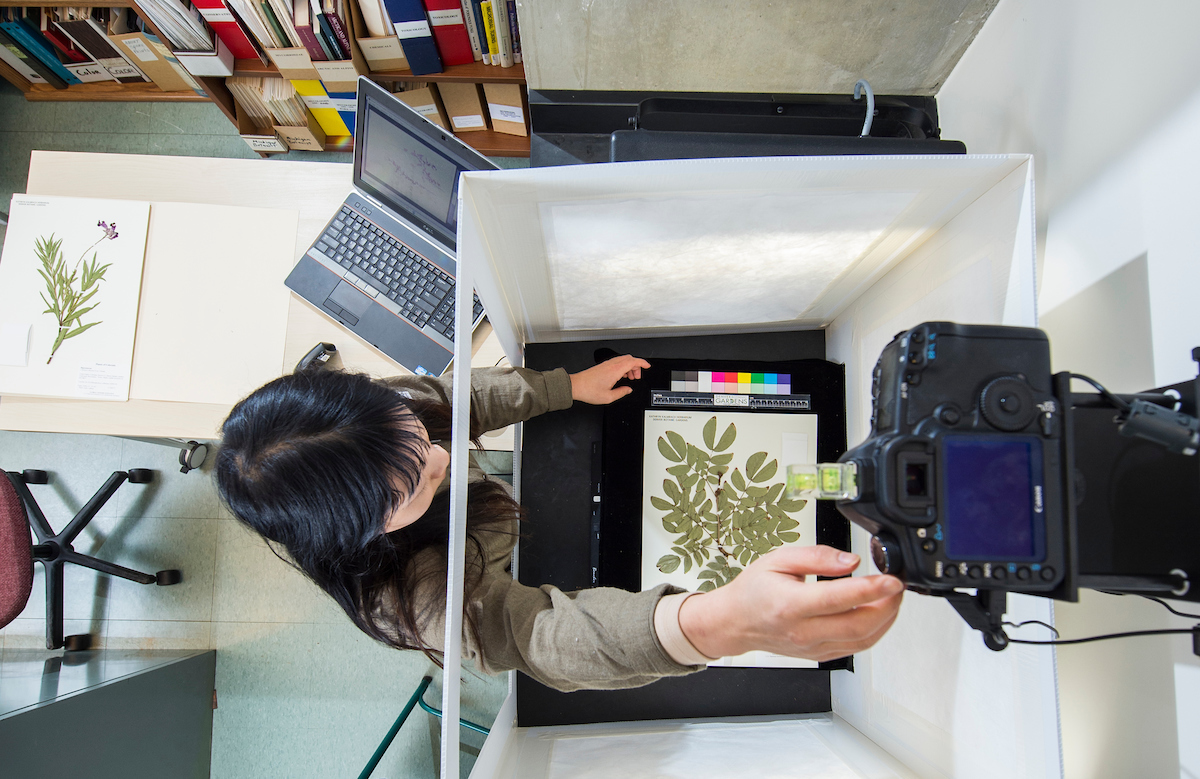

Tech to Connect

The demanding work of plant conservation often leaves little time or energy to share its importance and impact with the broader community. Detailed data and herbarium vouchers that are vital in documenting species distribution and diversity as well as population trends over time can be tucked away in herbarium cabinets and computers. The amazing story of how a species adds life and color to intermountain steppe habitats is shared only among the handful of people who track these species closely. But technology has allowed Denver Botanic Gardens to more easily go that extra step of sharing their data and telling their plant stories to a wider audience. Through technology, the Gardens are able to connect to both researchers and the public, thereby expanding the reach of their work.

Seeing the Value of Plants

While Colorado plants of conservation concern are incorporated in the living collections with many on display at Denver Botanic Gardens, most of the conservation work happens out of the public eye. Labs, herbaria, and nurseries are tucked away, and field sites are dispersed across Colorado. Creative use of technology at the Gardens not only helps visitors connect with the conservation science its scientists undertake; it also helps them view plants and nature through a scientific lens. Much of this outreach takes place within the Science Pyramid at the Gardens, an impressive piece of architecture that draws on nature for inspiration in its design and pulls visitors in to learn more about Colorado and the steppe environments of the world. In Colorado, these shortgrass prairies and sagebrush valleys are habitat for the rare species studied by the Gardens’ scientists.

Within the Science Pyramid, exhibits full of interactive technologies – touchscreens, sound, video, and even a globe – share tales of science and plant exploration. Tall, slim structures reminiscent of an aspen glade, feature digital overviews for visitors showcasing the biodiversity of Colorado, plant adaptations, and the science conducted by Gardens staff. Interactive boulder-like structures provide detailed vignettes of conservation and citizen science efforts to visitors. The integrated touch screens of a large topographic map table not only introduce the visitor to the diversity of ecosystems in Colorado; they also allow the user to explore images of major ecosystems and highlight similar ecosystems in other steppe regions around the world. Bringing the outdoors in, various components of the Science Pyramid exhibits respond to the outdoor temperature and windspeed.

Yet, the public need not visit the Science Pyramid, nor even the Gardens, to learn more about the work being done to save plants. Videos aren’t just for exhibits, but can be found on the Gardens’ YouTube channel. Here, a viewer can be transported to the Colorado steppe as a team monitors the National Collection species Colorado hookless cactus (Sclerocactus glaucus) or to the Gardens’ Chatfield Farms site as they work to restore the creek that runs through it.

These technologies help connect the public to nature. But the tales also empower them to get more involved. Visitors to the Science Pyramid, the YouTube channel, or even the Gardens’ blog, gain an understanding of the breadth and depth of scientific programming at the Gardens. They are also invited to learn about citizen science efforts in which they can participate.

Sharing Valuable Data

Bringing experiences from the field and the lab to others isn’t just a key part of outreach; it is an important part of participating in the scientific community. As such, Denver Botanic Gardens doesn’t collect plants from across Colorado just to keep them locked away in the herbarium. They take advantage of technological advancement, and open access data sharing efforts, to publish the information describing their specimens on various internet databases so that scientists worldwide can incorporate the data into their research and statistical models. What’s more, it’s not just their herbaria data that are shared.

Denver Botanic Gardens has worked hard in the past few years to standardize all of their data collection. This allows them to better combine data from ecological and floristic projects and to expand its use. Data is entered using Darwin Core standards which helps them share data with the broader scientific community in a standardized way. Thus they can share genetic data through the Global Genome Biodiversity Network, specimen data through iDigBio, ecological datasets on GBif, and more. All of their efforts help more scientists work towards increasing our knowledge and understanding of the plant world, hopefully helping us save more plants.

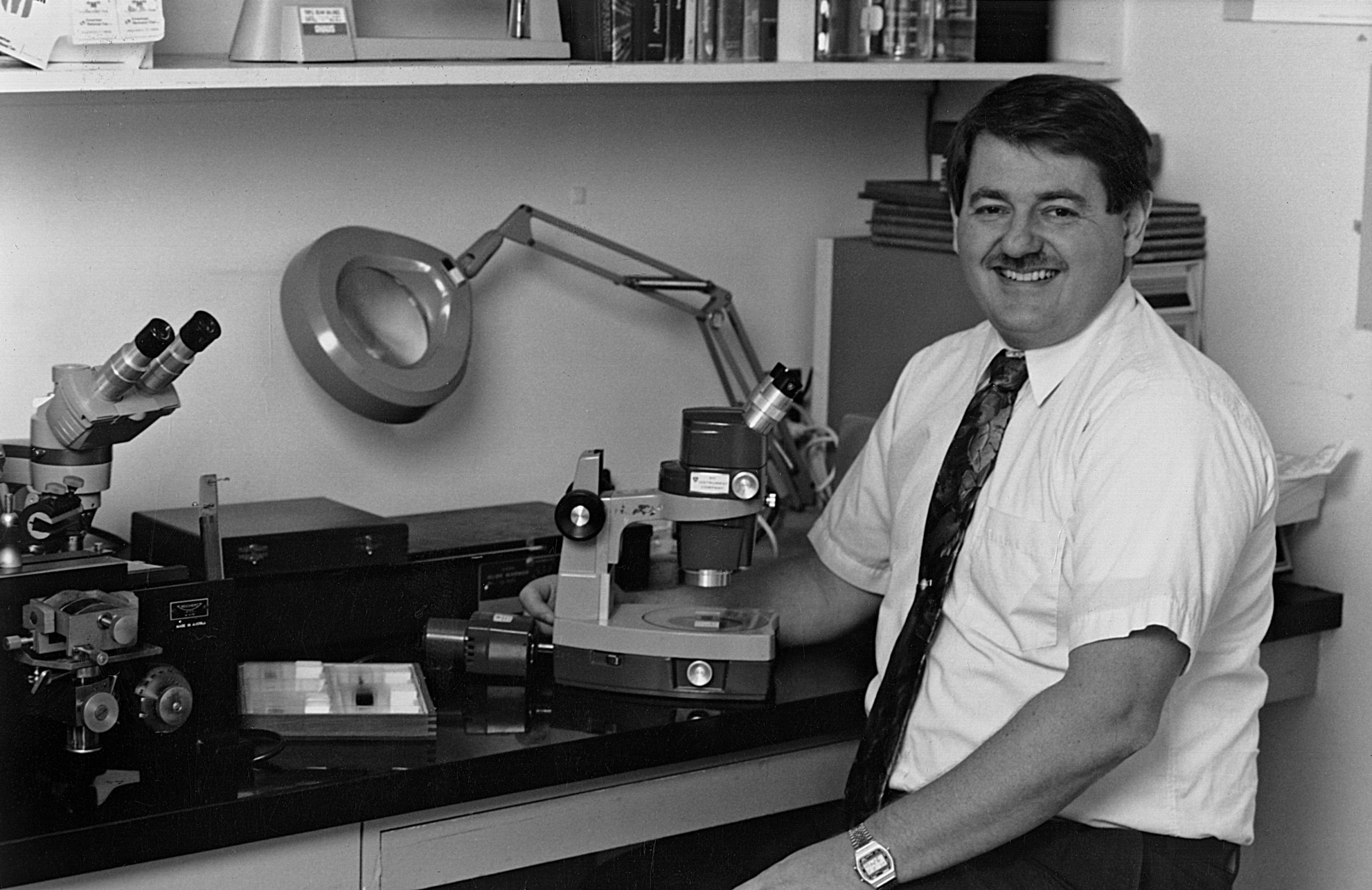

Edward Schneider, Ph.D.

Trustee Edward Schneider Ph.D., currently serves as President and Executive Director of BRIT, but has also served as the director of Santa Barbara Botanic Garden and University of Minnesota Landscape Arboretum and ushered those organizations into the CPC network. For his efforts at these three institutions, he was awarded CPC’s Star Award this year.

Where did you grow up? What is your favorite hometown plant?

I had the privilege of growing up in Cashmere, Washington, small town in the apple and fruit country. This upbringing instilled in me at an early age the economic importance of plants. My favorite hometown plants were the conifers and fir trees that populated the countryside landscapes.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

During my high school years. I had the good fortune during my junior-senior year to be part of a National Science Foundation Grant at the University of Nevada, Reno where I spent a summer doing study and research at the Desert Research Institute (DRI) with Dr. Fritz Went.

What was your path to becoming Director of a botanical garden (i.e., education, career path)?

After completing a doctorate in botany at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), I began an academic career at Southwest Texas State University in San Marcos, TX. Ascending through the professorial ranks, I eventually was appointed Dean for the College of Science. I found the administrative functions rewarding, including donor prospecting. One day a former mentor at UCSB called and asked if I would consider running the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden. The rest is history.

When you aren’t busy saving plants, what do you like to do with your free time?

My wife Sandy and I love to travel, visit gardens and explore natural areas.

When did your garden become a CPC Participating Institution? Do you know – and can you share – the impetus for joining?

Actually, I’ve guided four Gardens into the CPC Participating Institution network: Santa Barbara (1995), University of Minnesota Landscape Arboretum (2009), Botanical Research Institute of Texas (2016), and the Fort Worth Botanic Garden (2018). In each garden, geographic location and the need for Plant Conservation were the driving forces for joining CPC.

In your opinion, how has your garden benefited from being a CPC participating institution?

Numerous benefits and rewards come to Participating Institutions: knowing that your efforts help save plants; networking with local, regional and state-wide individuals who share the same concerns for saving plants; participation in the annual CPC meeting with colleague’s from other gardens who are doing the same kind of work; and increased visibility for the garden among community members, donors, and philanthropists.

What aspect of your garden and its work are you most proud of?

If we are still focused on the outcomes for conservation work, I am most proud to have witnessed the capacity of each Participating Institution garden to expand; to see conservation become a growing element of the garden’s mission, and most important to prevent loss of our critically imperiled plants.

What accomplishment are you most proud of achieving as Director of your garden?

Ensuring the financial stability of the Garden and its programs and growing revenue streams that add new resources to existing and new program expansion. Encouraging the professional development of staff to become leaders in their program areas.

What is the biggest challenge you face as Director of your garden?

Providing the resources needed by staff and keeping programs relevant to stakeholders.

What do you think is the single most important thing your garden does to save plants?

Forming collaborative networks and improving channels of communication among all constituents.

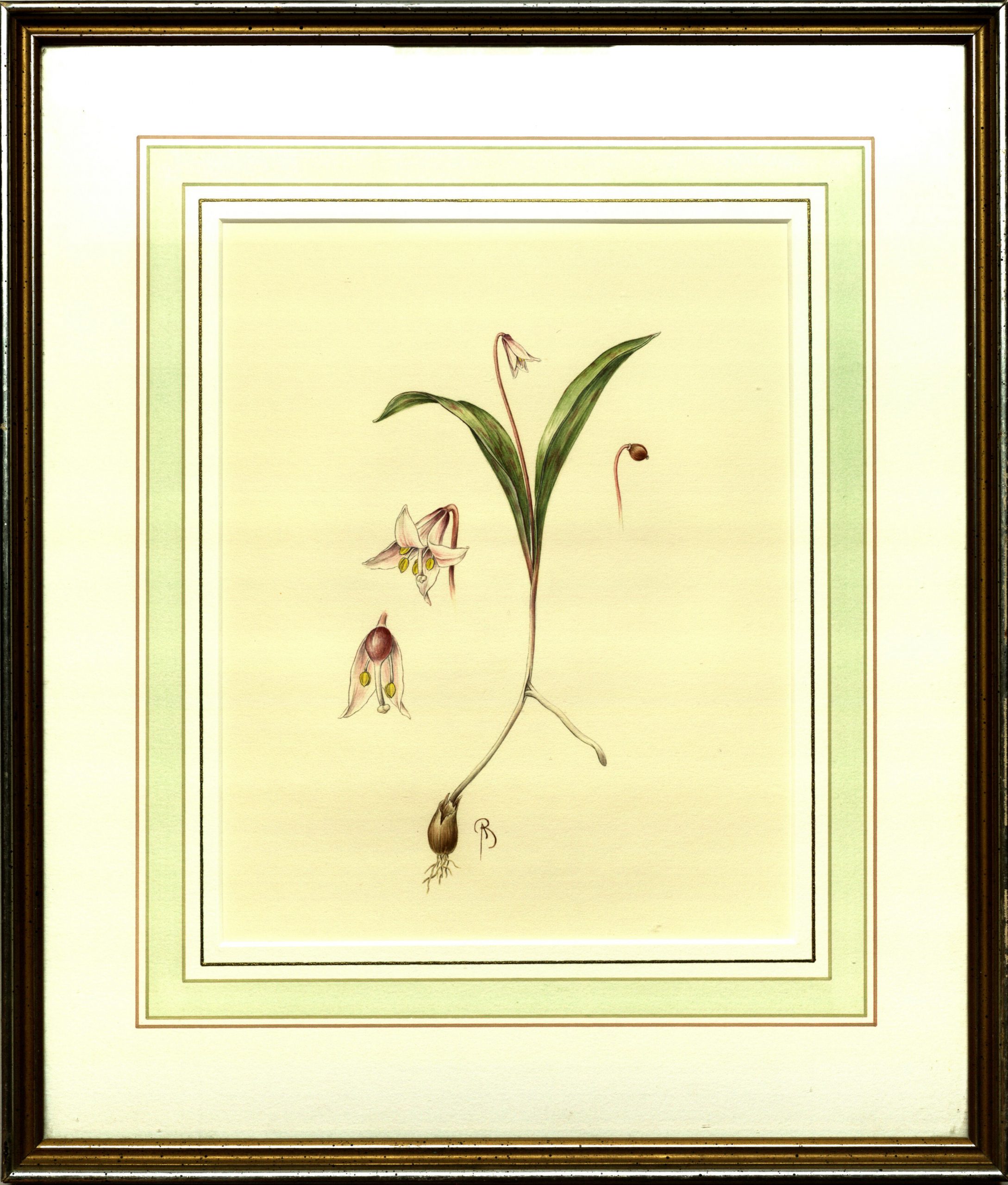

What is your favorite National Collection species?

All of them are my favorite (and I especially liked the watercolor images done by Bobby Angel as part of a CPC commission), but if I had to choose one, my favorite is the Minnesota dwarf trout lily (Erythronium propullans).

Why do you think it is important for Garden Directors to be represented on the Board?

Garden Directors have played a critical role, historically, as all PIs were Gardens. With the CPC network expanding, other type of institutional Directors, institutions that are not gardens, but also play a critically important role in conservation, may be asked to join the CPC Board of Directors. Looking forward, the role of Garden Directors needs study and clarification.

What prompted you to agree to become a Trustee for CPC? What unique perspective do you think you bring to the board?

I was asked by the CPC Director to please consider the position, which I gladly accepted. I bring the perspective of successful administration of multiple institution, skills in governance, fundraising, and the building of collaborations.

What excites you the most for CPC moving forward?

Expanding the CPC network and the partnership with San Diego Zoo Global.

-

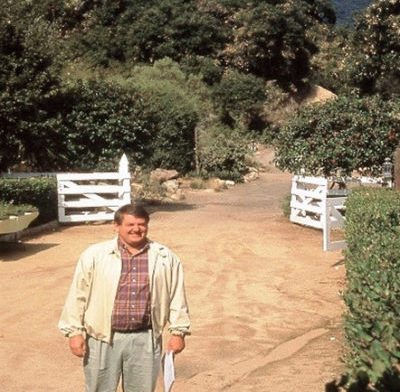

The first institution that Dr. Schneider brought into the CPC network while he was at the helm was Santa Barbara Botanical Garden in 1995 – the year of this photo. -

Water color illustration by Bobby Angel of the endangered Minnesota dwarf trout lily (Erythronium propullans). -

In 2006, the Botanical Society of America marked their 100 years as an organization with the creation of the Centennial Award. Both Dr. Edward Schneider and Dr. Peter Raven were presented the award, recognizing outstanding service to the plant sciences and the Society.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today