Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

June 2019 Newsletter

This month’s issue of SavePlants highlights one of the most inspiring of all plant families, the orchids. Orchids possess the trifecta of desirable traits – scent, beauty and diversity. As such, orchids are coveted by enthusiasts, collectors and plant growers alike. With over 30,000 kinds of natural species, and even more hybrids and cultivars, orchids are one of the most sought after and economically valuable plant families. Unfortunately, what makes orchids so irresistible also makes them prone to exploitation and loss. Many orchids are among the most imperiled species on the planet. And of these, many are difficult to grow and maintain in cultivation, seeds are difficult to store, and conditions in the wild are increasingly threatened. Fortunately for us and the orchids, CPC Participating Institutions are hard at work knowing and growing these amazing plants to ensure their long term survival. Read on to learn about orchids and the dedicated efforts to preserve them for the future.

Onward!

The Land of a 10,000 Lakes – and Dozens of Orchids

In 2015, the University of Minnesota Landscape Arboretum (MLA) won the state lottery. Well, they were awarded a grant through the Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund – funded by the state lottery. The grant helped their fledgling Native Orchid Conservation Program reach new heights.

When first developing their conservation program, MLA sought to focus their work on a group of plants in need that had the appeal to draw visitors and the broader public into plant conservation. As Curator of Endangered Plants, David Remucal, states, orchids “are one of the most emotionally evocative plants for people.” With that potential visitor connection and so many biological unknowns for temperate orchids, the state’s 48 native orchid species were a clear choice as a conservation focus. Giving themselves the mandate to preserve all of Minnesota’s native orchids, 20% of which are rare or endangered, and none of which are exactly common, MLA has put its lottery funds to great use. Over 30 of the species are represented in their seed bank, they have expanded to cover other parts of the country, collaborated on reintroductions, and participated in research to better understand orchids’ mycorrhizal fungi associations.

Handing over the first couple thousand rare small white lady’s slipper (Cypripedium candidum) and moccasin flower (Cypripedium acaule) to collaborators in Wisconsin for reintroduction was a thrilling moment for the program. The seedlings resulted from years of work collecting seed, working through their unique propagation needs, and waiting patiently for the resultant plants to be of suitable size. The hand-off of those seedlings moved the Native Orchid Conservation Program’s work from research to application. More reintroduction and restoration projects with orchids are on the horizon. For example, the white lady’s slipper will be part of The Nature Conservancy’s effort to restore an agricultural tract to a prairie ecosystem. Using orchids during an active, full-landscape restoration isn’t something that is really being done, so the team is excited by the possibilities for the project and its monitoring data.

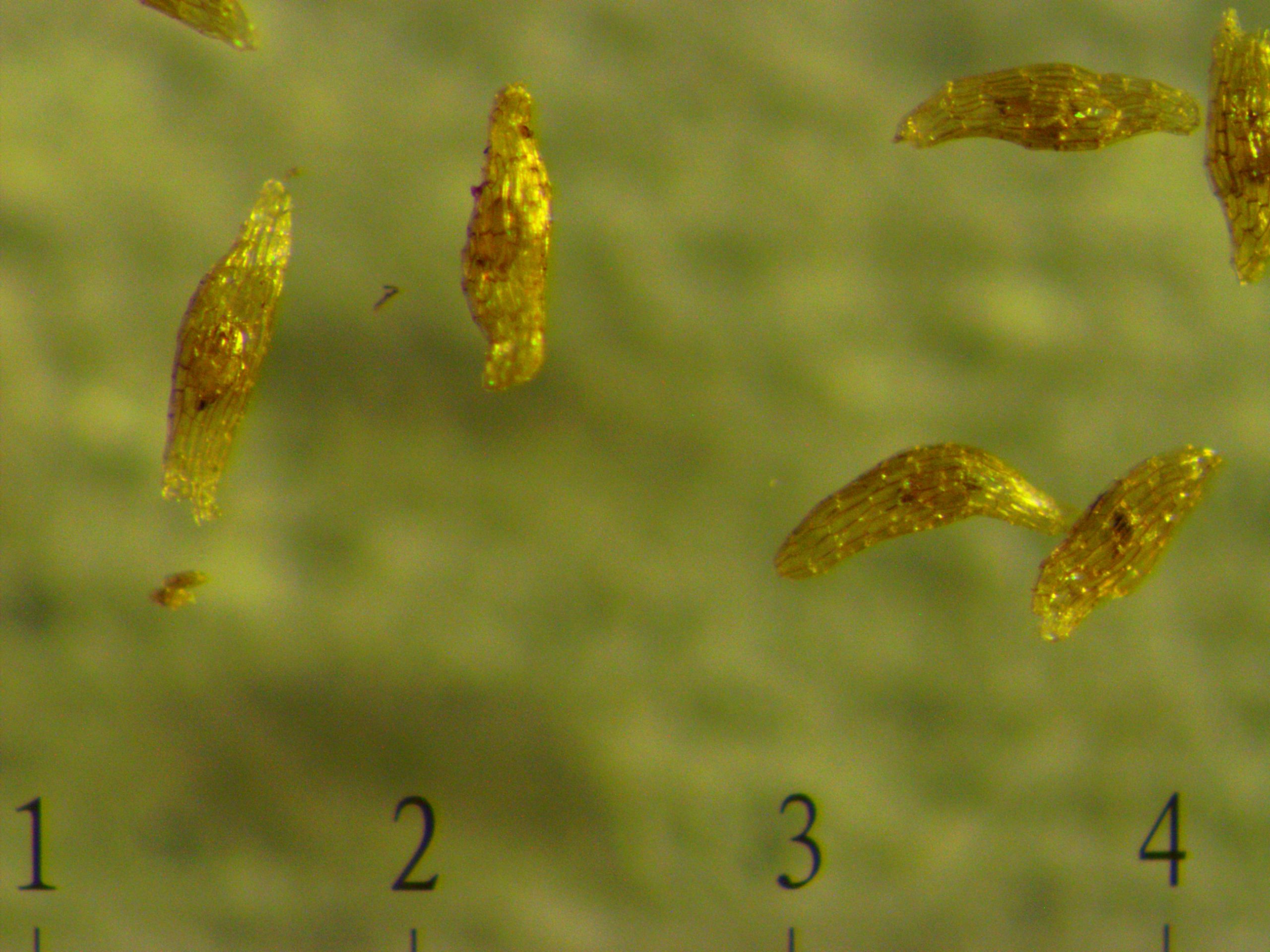

Though a few species are being readied for restoration, the core of the Native Orchid Conservation Program is seed banking. Just locating populations and timing collections can be a challenge. The less flashy or more common species, such as green adder’s-mouth orchid (Malaxis unifolia) and blunt-leaved orchid (Platanthera obtusata), have proven the most lacking in initial information. Their great progress in seed collecting comes from an ability to draw on many sources of information – state biologists, academics, iNaturalist, local land stewards, and more – to learn more about the location, population sizes, and phenology of their targets. Once the seed is acquired, the team works species-by-species to figure out the best storage protocol and testing their viability – the seed banking basics.

While making big strides in ex situ conservation, the MLA program has also worked to better understand the orchid-fungi relationships. Many orchids have delicate relationships to fungi and soil – relationships threatened by changes in land use, disturbance levels, and climate change. Some of their many partners in this area are found all the way over in Belarus. Sharing a few rare species, and one Belarusian native/Minnesota invader, makes for an interesting opportunity to understand orchid-fungi affinity. And orchids have a few other delicate relationships worth studying: orchid-pollinator relationships and ties to specific hydrologies. The complex biology of orchids means that MLA’s Native Orchid Conservation Program will have plenty to research, to apply, and definitely identified a group in need. You might say that Minnesota orchids won the lottery in getting such a dedicated team on their side.

Connecting With Orchids

North American Orchid Conservation Center

Based on information from

Julianne McGuinness, Program Development Coordinator,

and Dennis Whigham, Founding Director

Since its inception, NAOCC has connected more than 50 collaborating entities around North America, and is growing. NAOCC plays a variety of roles with regard to the many different types of partner groups, which vary from universities and botanical gardens to schools, independent botanists, and land trusts. For some, NAOCC is a research partner in guiding scientific trials, and for others, an educational resource or restoration consultant. The overarching leadership role, however, is to be a “bridge” – a communication facilitator and connector to bring the people and groups working on orchid conservation together to tap into the power of collaboration and move the collective efforts forward. Working alone, each initiative or project may make a “drop in a bucket” towards conserving native orchids for future generations, but working together, the collaborators can turn that drop into more powerful gallons or barrels.

NAOCC has had great success in building up the collection of both orchid seed and their mycorrhizal fungi in regional seed and fungal banks. The Smithsonian Environmental Research Center now has the largest living collection of orchid mycorrhizal fungi in the world – and NAOCC researchers are only starting to “scratch the surface” with regard to capturing the diversity and functionality of the mycorrhiza.

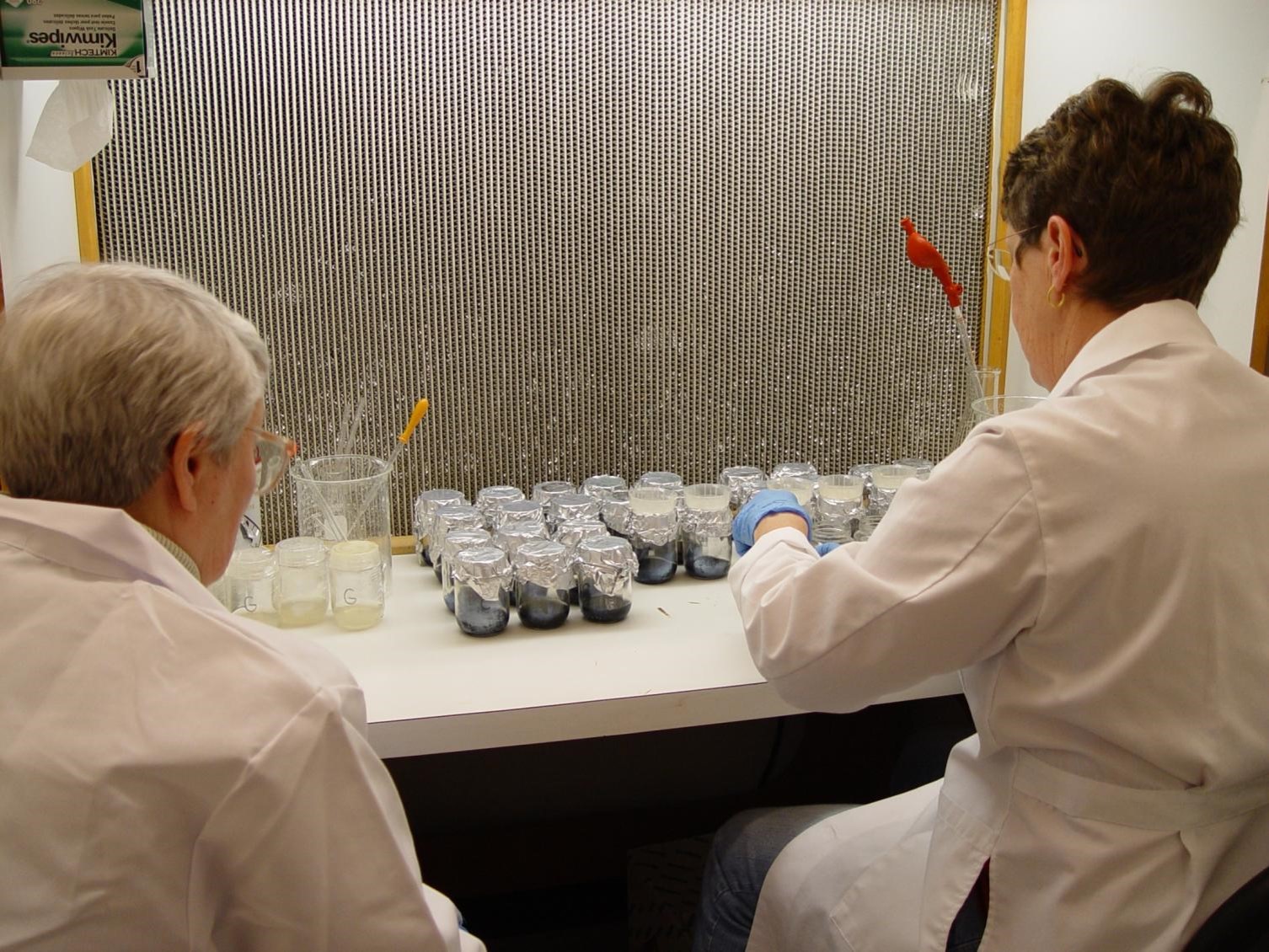

The interaction between orchids and mycorrhizal fungi is especially fascinating, and may be a key to conservation efforts. One of NAOCC’s goals is to obtain roots from all North American native orchid species within each physiographic province in each US state and Canadian province – with an objective to isolate, culture, and identify the specific mycorrhizal fungal species associated with all native orchids, and every life history stage. Thus far almost all of the orchid mycorrhizal fungi that have been identified using molecular techniques are new to science! NAOCC is making progress towards this goal through the assistance of Dr. Larry Zettler’s lab at Illinois College, which engages college students to assist with the isolation and identification of fungi from orchid roots sent from NAOCC collectors far and wide – including from volunteers of the Native Plant Trust in New England, Mt. Cuba Center in Delaware, land trusts and preserves in Wisconsin and Michigan, and so on. Indeed, Rach Helmich, a student in Dr. Zettler’s lab, recently paired mycorrhizal fungi with seeds of the white fringeless orchid (Platanthera integrilabia) – both stored for 28 years – to achieve successful germination.

Engaging with students in research labs isn’t the only educational connection NAOCC maintains. The Go Orchids website is an educational tool modeled after the Native Plant Trust’s Go Botany site – it is a “one-stop shopping” resource for the public and professionals alike to find information and identification detail about all of the native orchids of the US and Canada. It is now widely used and appreciated by citizen science volunteers, photographers, botanists, naturalists, landowners, and schools. NAOCC’s outreach work has expanded beyond the web, too. Orchids-in-the-Classroom is a new initiative – a collaboration between NAOCC, the Fairchild Botanical Garden, and Longwood Gardens to bring orchid science into middle and high schools in the Maryland and Washington, DC area and Miami. Students have helped develop propagation protocols for two native orchids – the downy rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera pubescens) and the pine pink orchid (Bletia purpurea). This program has been so successful with engaging students in hands-on orchid conservation science that NAOCC is now planning to develop the initiative into a nationwide curriculum.

Ensuring the conservation of more than 200 native orchids within the U.S. and Canada will be no easy feat. The task is now becoming easier with the connections NAOCC has developed in order to better understand these special temperate orchids and their unique connections to their habitats.

Blooming Successes in Georgia

The Atlantic Botanical Garden (ABG) team had hoped to see some population increase of the white fringeless orchid (Platanthera integrilabial), when they went out last summer to monitor one of the restoration sites on privately-owned lands. They had started the project just two years earlier, removing the woody plants shading the area to provide better habitat for the white fringeless orchid and weren’t expecting too much of a change from the remaining three orchids that comprised the original population. The team definitely wasn’t expecting to arrive at the site and find a blooming field of 24 individuals. The whole team excited by the remarkable progress, Emily Coffey, Ph.D., noted how gratifying it was to see the hard work they put in to saving this species paying off.

Though it was just two years of active restoration at this site, the hard work to save the white fringeless orchid started many years ago. Atlanta Botanical Garden has led efforts to collect seed, store seed, propagate, and produce plants for ex situ safeguarding as well as in situ population augmentations since efforts to help the species in Georgia began. They lead an extensive partnership that public agencies, land managers, regulating agencies, interns, and more, and have recently expanded their work into other states in the orchid’s range, North Carolina and Tennessee.

White fringeless orchid is a standout species, with beautiful clusters of delicate white flowers, being considered for the listing under the Endangered Species Act. Threatened by the usual suspects (e.g., habitat loss, invasive species), as well as an increase in shading from woody plants due to a decline in fire and lack of active land management, in addition to roadside management practices such as mowing and herbicide application. When ABG began their work on the species, there were just nine populations in Georgia, hosting 120 individuals. Significantly, six of these populations were on private, unconserved lands.

Dr. Coffey notes that many of the major challenges to saving the species pertain to the need to work on private property. The team needed to introduce land management practices on private lands and set up conservation easements. Outreach became a large part of the project, as convincing private land owners to allow prescribed burns or mimicking fire’s impact through mechanical removal of woody plants was an important step. Some of the properties also had established rights of way – and so some of the outreach was directed at the Georgia Department of Transportation and Georgia Power to alter herbicide use and adjust mowing regimens to allow white fringeless orchid to flower and set seed. Persuading land owners and these large public entities took time – as well as patience and perseverance.

Patience and perseverance also come in handy in tackling the biological challenges of conservation work. ABG has been successful in handling those challenges as well, and not just with white fringeless orchid. The stately flower is just one species of twelve orchids in the garden’s ongoing conservation program. Focused on the Southeastern U.S. and Caribbean, they are applying their myriad of skills to a variety of other species in need. Their projects range from ex situ conservation of Kentucky lady slipper (Cypripedium kentuckiense), geographic surveys and predictive monitoring of many-flowered grass pink (Calopogon multiflorious) and Chapman’s fringed orchid (Platanthera chapmanii), to propagation and reintroduction of cigar orchid (Cyrtopodium punctatum).

For each species they work with, the team makes sure to celebrate the successes where they can. Conservation can be hard, and focusing on successes keeps moral up. Like the day last year where the monitoring team was rewarded with a beautiful bloom. They are excited to see how they have done this year and hopeful that they’ll have another increase in blooms when they survey in August.

The Orchid Conservation Program at Longwood Gardens

By Peter J. Zale, Ph.D.

When founder Pierre S. du Pont purchased the property where he would create Longwood Gardens, he did so to conserve a historic collection of trees and old growth forest remnants, solidifying conservation as part of the legacy of the gardens. Not long after, he began construction of the conservatory complex, a first step towards one of his primary goals of developing a world class collection of orchids. Several plants from his original collection remain today, and the collection has expanded considerably to become a “Core Collection” – a collection of the highest importance to the institution for its ties the founder’s legacy, display initiatives, and conservation value. Both conservation and orchids have been rooted in Longwood Gardens since the beginning, and when the idea to begin a formal plant conservation program was initiated in 2015, it was decided that native orchids would be a logical and strategic choice on which to build the program. The focus on native orchids not only provides a way to expand the current collection in a novel way and display orchids in the outdoor gardens, it’s also an avenue for expanding the scope of the plant exploration program, designing and conducting original, applied horticultural research, and forming new partnerships with various agencies interested in restoring native orchid populations in Pennsylvania and the mid-Atlantic.

Since the program’s inception it has expanded to include not only regional native orchids, but also species from across the U.S. and temperate terrestrial orchids from around the world. The goals of the program are 1) to stem the loss of local, regional, and global orchid diversity, 2) build orchid collections with high conservation value, 3) disseminate research and germplasm for collections development, and restoration purposes, and 4) dispel horticultural myths surrounding some species. We use a multi-faceted, research-based approach that involves seed collection, fungal bank development, seed germination, in vitro seedling development, greenhouse acclimatization, collections development, and restoration. To accomplish this work, developing partnerships with state government agencies and conservation-minded organizations has been paramount. Species included in the program are chosen by Longwood staff to meet various needs, but also in conjunction with numerous partners that have expressed concern about the status of certain species across the region that may need future restoration efforts or could benefit from ex situ collections development.

The first taxon in our program was the large yellow lady’s slipper (Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens). This flagship species has become locally rare in Chester County due to habitat loss, a booming white-tail deer population, and pollinator limitation. At the beginning of the project, only a single, small population was still known in the county. Despite its wide natural distribution and availability in the commercial horticulture industry, propagation protocols still required work and local genotypes (plants adapted to this specific habitat) were not available. Using hand pollination and subsequent embryo culture, we have been able to successfully propagate this species in large numbers that are being used for collections development and restoration of the small source population. Plus, the resulting propagation protocol has been proven successful for other Cypripedium species. Expanding beyond yellow lady’s slipper, other genera of native orchids have been included in the program: Arethusa, additional Cypripedium, Goodyera, Platanthera, Spiranthes, and many others.

One of the early successes of the program is checkered rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera tesselata), a state endangered species that reaches the southern limit of its distribution in Pennsylvania. Working with the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR), we collected seeds of this species in 2016 and devised a set of asymbiotic (that is, without its associated mycorrhizal fungi) germination experiments to learn more about its propagation requirements. There is conflicting information on the propagation of Goodyera, and it has been suggested that it is difficult to propagate. Our experiments resulted in a high rate of germination that yielded hundreds of seedlings that were successfully grown in vitro and acclimatized to greenhouse conditions. In October 2018, 78 seedlings were transplanted along two transects into the preserve where they were originally collected. The restoration experiment was done in conjunction with partners from the Pennsylvania DCNR, Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program, and Mount Cuba Center. Data from this study will help determine the best practices for re-introducing orchids to the wild and the information will directly influence and inform similar future studies with other species of native orchids.

While still a young program, Longwood Garden’s conservation work has made great strides in saving orchids. Building on horticultural strength and partnership development, the program promises to extend this success to even more species both domestically and internationally to help protect threatened orchids.

Treasured Collections

Orchids have proven enduringly popular, and they have been called the “pandas of the plant world” because of their rarity and beauty. In many cases, they also serve as a flagship for conservation, raising public awareness of the need to protect rare plants and their fragile habitats. At Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, an impressive collection of orchids rotates through display areas so that the public can enjoy the wonders that the Gardens’ researchers have brought back from the tropics and subtropics. Like the other collections at Selby, they serve the broader purpose of elucidating patterns in plant diversity and distribution.

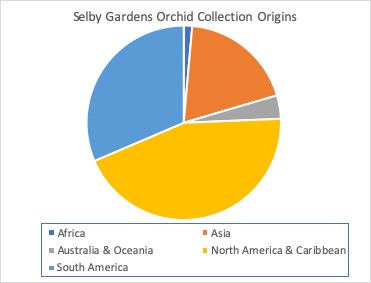

Ex situ collections of wild species are important for conservation efforts as global biodiversity continues to decline at an alarming rate. To this end, Selby Gardens aims to be a leader in programs of research and conservation, and to help stabilize or restore wild plant populations. As the world’s only botanical gardens dedicated to the study and display of epiphytes (plants which grow on other plants), the majority of Selby Gardens’ collections consist of species from epiphyte-rich plant families – including Orchidaceae, but also, Bromeliaceae, Araceae, Cactaceae, and Gesneriaceae, and various families of ferns and lycophytes. Much of Selby Gardens’ living collection is housed behind-the-scenes, in over 20,000 square feet of greenhouses, though collection plants often rotate on display in the public Tropical Conservatory. Fittingly for one of the largest families of flowering plants, the Orchidaceae has the most representatives in Selby’s living collection, with over 1,300 species represented, originating from more than 50 countries.

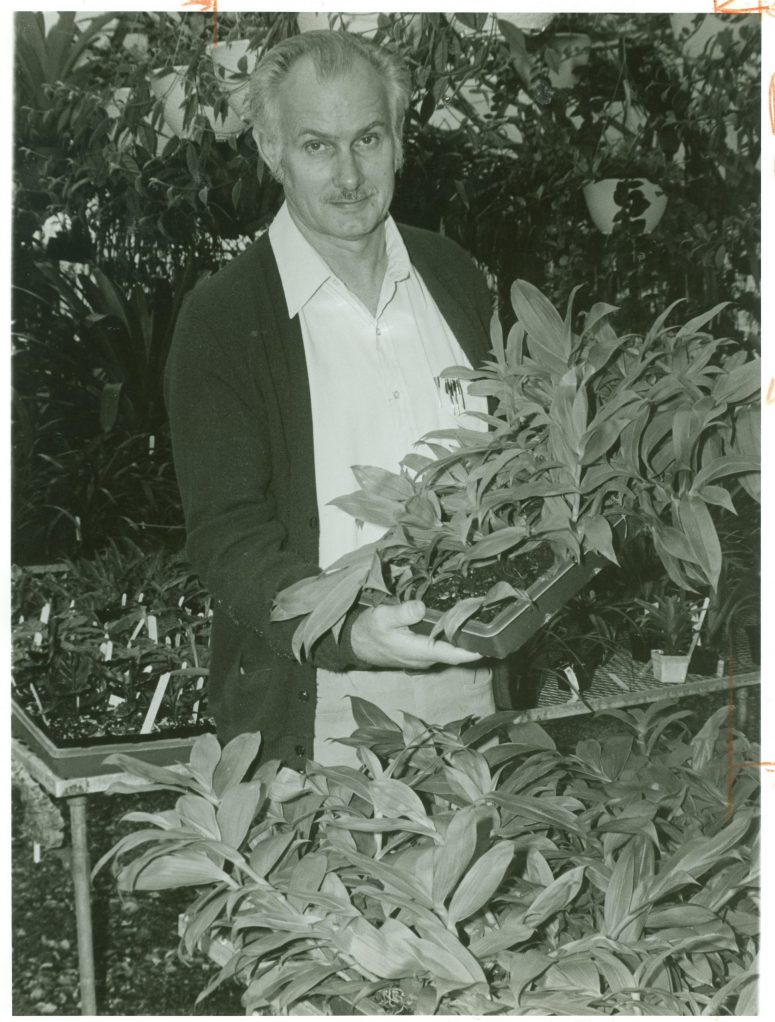

Not only do these collections increase our knowledge of the orchid family as a whole, they help staff learn more about the biology and horticulture of these species to support conservation efforts. Conservation has been a part of Selby Gardens from the very beginning. The Gardens was founded in 1973, and one of the senior scientists and founders, Dr. Calaway Dodson, was already showing off a flat of the extremely rare orchid, Epidendrum ilense, being prepared for out-planting in the wild in 1978 (pictured below). Similar work continues today, as Selby Gardens endeavors to not only build up their living collection, but to employ their botanical and horticultural skills in support of rare plant species in Florida and around the world.

Jason Ligon

Applying the horticultural expertise necessary for maintaining botanical gardens to conservation, Jason Ligon’s work exemplifies an important role botanical gardens can play in conservation. The special requirements of orchids have been dialed in by Atlanta Botanical Garden staff to produce plants for the garden and reintroductions, a process Jason has been a key part of while volunteering at the garden and as the Tissue Culture and Seed Bank Coordinator.

When did you first fall in love with orchids?

I had such a once-in-a-lifetime experience working with orchids while studying abroad in Equatorial Guinea. Having that opportunity to see orchid diversity in the wild forever made this family of plants special to me.

What was your path to becoming the Tissue Culture & Seed Bank Coordinator?

Lots of free labor. I interned with the National Park Service and assisted in field research abroad before volunteering for three years at the Atlanta Botanical Garden in multiple capacities. Above all my favorite volunteer position was in the tissue culture lab learning from then Conservation Horticulture Manager Matt Richards. I then worked for four years for the Fuqua Orchid Center here at ABG. That gave me the chance to hone my greenhouse horticulture skills and continue to monitor the seedlings that had been produced from the lab. Now as Tissue Culture & Seed Bank Coordinator I have an amazing opportunity to improve the lab’s yield by addressing issues I had observed in the previous 7+ years while around the garden.

Can you share why micropropagation is a powerful tool in the conservation toolkit?

Micropropagation is such an excellent technique because it is so concentrated. In the lab, versus in the field, you can grow and monitor development of plants in a smaller, more controlled environment. This is especially useful for species with low success rates facing high pressure in situ.

What about working with orchids has surprised you?

You would think that all orchids would share similar characteristics. That may be true when it comes to flower morphology, but the commonality stops there. At a glance, all the containers of seedlings on the shelf in the lab may look the same, but surprisingly many orchid seeds respond drastically to minor changes in vitro. Often a tweak in the recipe of temperature, growth media composition, dormancy length, or surface sterilization technique can change the outcome of a species’ growth.

Are the challenges of conserving temperate orchids different than those of tropical orchids? How have your program’s efforts met those challenges?

In some ways yes. The two categories of orchids have different horticultural needs in the lab that we must always keep in mind. For example, the temperate growing terrestrial orchids need a dormancy period whereas the tropical orchids do not. Also Atlanta’s climate is temperate so traveling farther to collect seed and monitor projects in tropical zones can be problematic. However, to help meet the challenges of our more distant or labor intensive projects, ABG has adapted by establishing partnerships with organizations beyond Georgia and by hiring ample staff that reach beyond Atlanta.

Please share one of your orchid conservation projects and how what you’ve learned could benefit others working to conserve orchids.

I recently became more involved with ABG’s partnership with Jardín Botánico de Quito to conserve the lady slipper orchid, Selenipedium aequinoctiale. Its extremely restricted habitat range in Ecuador puts it at high priority for conservation concern. Through this project, I’ve learned that the shared network of resources is undoubtedly stronger than either organization attempting to pursue conservation efforts alone.

What has been the most challenging aspect of your work?

A lot of what is known to work in ABG’s tissue culture lab has come from trial and error, and learning from those failures and successes. My biggest challenge so far has been honing in on the unexplored in vitro methods that could improve the scope of our operation. Cross referencing new micropropagation research against our historical experimental data has been both frustrating and fun.

Beyond propagation, you have helped with recovery efforts of several species. How has your horticultural background helped inform these efforts?

I’m thankful to have grown so many species of orchids in my greenhouse horticulture background. Now everything else seems easy. To me, horticulture at its core is observing plants in detail over time. That skill can then be taken into the lab or field to make best restoration decisions.

-

Jason visits Ecuador through ABG’s partnership with Jardín Botánico de Quito. -

Visiting habit range in Ecuador to study lady slipper orchid (Selenipedium aequinoctiale) conservation. -

Jason Ligon, Tissue Culture & Seed Bank Coordinator, Atlanta Botanical Garden teaching orchid care at Lockerly Arboretum.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today