Desert Botanical Garden's Herbarium: A Crucial Resource for Botanical and Conservation Research

A herbarium (herbaria, pl.) is a collection of dried herbarium plant specimens collected over broad geographic ranges over many years for study. There are nearly 100 ways we use herbarium specimens, a number that will increase in the future. They provide basic information to understand the world’s biodiversity by providing plant identification, distribution, morphological, geographical, phenological, geological, cytological, molecular, climatological, biochemical, ecological and evolutionary data. They represent a plant growing at a particular place and ecological niche at a particular time. Specimens provide information on the health of an ecosystem. Future generations will use specimens in ways we do not yet know.

Who knew more than 20 years ago that herbarium specimens could provide DNA that facilitates our understanding of the evolution of plants and the identification of new species and the processes by which new species arise? Or that specimens could provide material to use in climate studies that are so important today? Both of these uses are critical for addressing conservation issues.

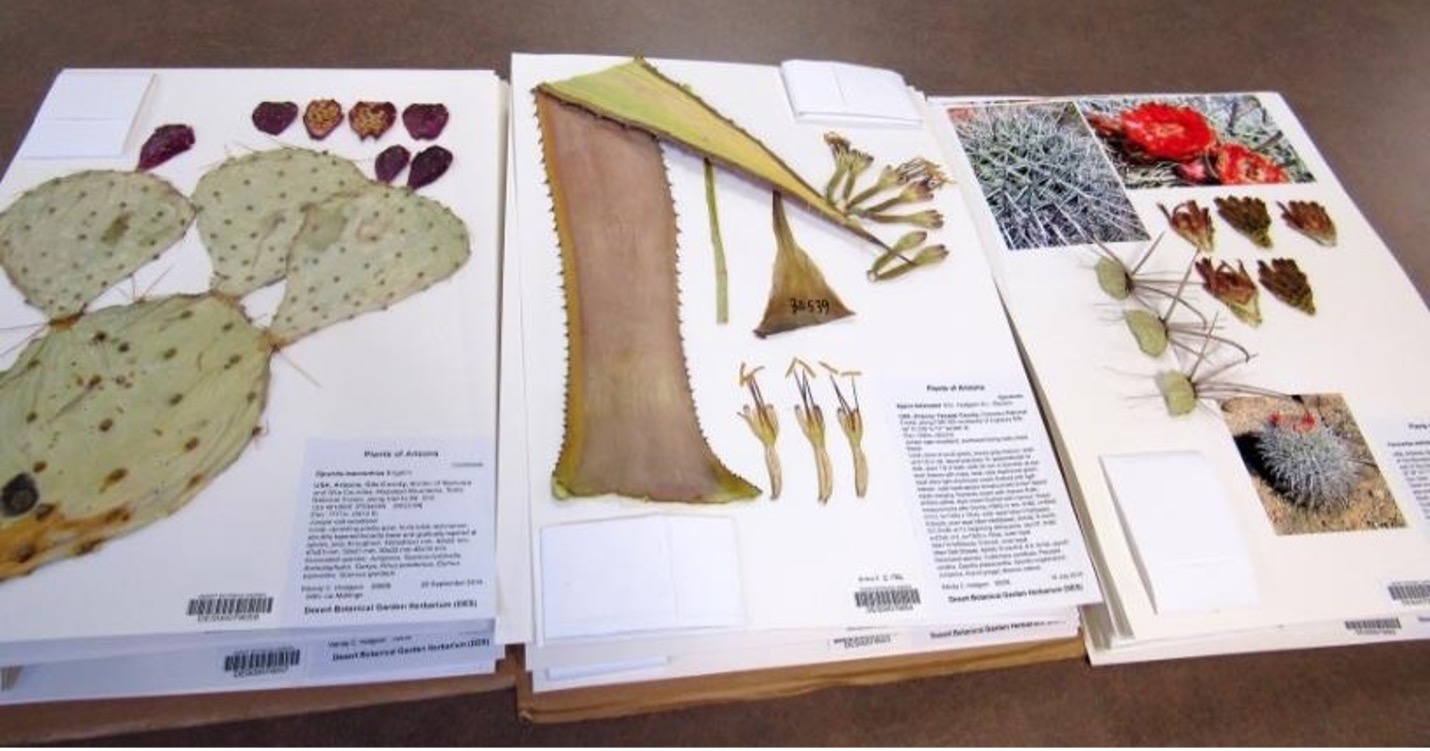

We credit Luca Ghini (1490-1556) with mounting dried plants on paper, a practice that spread over Europe by his students. However, he glued several specimens on a page inserted into a book, thus placing them into a fixed order from which no one could remove without destroying the specimens. In 1751, the Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus advised people to mount one specimen per sheet rather than binding the sheets together and storing them in a specially built cabinet similar to those we use today, so one can insert, remove and reinsert individual sheets easily at any place or time, allowing for more growth. If only Ghini and Linnaeus knew what the impact of their ideas would be on the world centuries later!

Desert Botanical Garden’s herbarium in Phoenix, AZ is the largest herbarium in Arizona that is supported by a nonprofit institution and is the fourth largest herbarium in the state. E.R. “Jim” Blakely, Desert Botanical Garden’s Assistant Botanist, assembled the Garden’s first set of herbarium sheets in 1950, and under J. Harry Lehr’s direction, the herbarium grew from a modest start of approximately 2200 specimens to become a designated National Resource in 1976—one of only 105 herbaria in the nation to be designated as such.

The herbarium continues to focus on the flora of arid and semi-arid regions of the world, with particular emphasis on the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico. Taxonomic specialties include the often difficult to press Cactaceae and the subfamily, Agavoideae, which includes agaves, yuccas and hesperoyuccas. Today, it houses over 100,000 specimens, including one of the best collections of cacti and agaves in the world, providing essential data for numerous taxonomic and systematic treatments, including Intermountain Flora and Flora of North America, respectively.

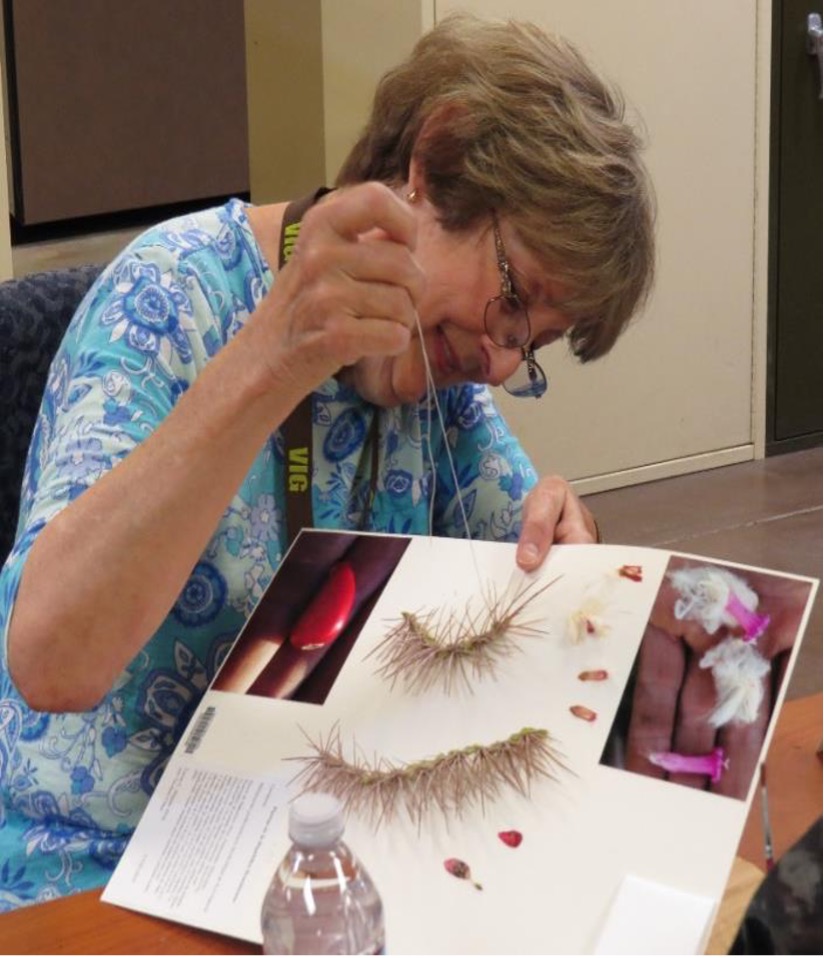

This is especially significant considering that cacti are the fifth most endangered organisms on the planet and many agaves are threatened. Because many of the Garden’s Living Collection has provenance data, they are especially valuable for study. Recognizing this, in 1993, Edward Anderson and I developed a formal program to voucher the Garden’s Living Collection conducted solely by Garden volunteers who have and continue to play an integral role in the herbarium’s growth for many years. We currently have 16 volunteers from all walks in life, including retired professors, helping in the herbarium.

The Garden’s herbarium and other herbaria continue to play an especially important role during these climate-challenging times. Climate scientists estimate that 41% of the land surface is arid and semi-arid. By the end of the 21st century, 56% will experience desertification, dramatically affecting human health, especially in deserts. Arid zones, including Phoenix and the greater Southwest, are laboratories providing scientists with numerous opportunities for study. Floristic, ethnobotanical, systematic, and eco-physiological studies in the Southwest, supported by herbarium specimens, are especially critical.

Herbaria, like the one at Desert Botanical Garden, not only preserve the botanical history of our planet but also provide critical data for current and future scientific research and conservation actions. As climate challenges and other threats to rare and native plants intensify, the invaluable resources and knowledge held within these collections will continue to be essential in understanding and protecting our natural world.

-

A volunteer sewing specimen on herbarium sheet at Desert Botanical Garden. Photo courtesy of Wendy Hodgson. -

A volunteer collecting material for herbarium specimens from Desert Botanical Garden’s Living Collection. Photo courtesy of Wendy Hodgson. -

Volunteers mounting specimens at Desert Botanical Garden's herbarium. Photo courtesy of Wendy Hodgson.