Alexandra Seglias

Our Conservation Champion, Alexandra Seglias, truly exemplifies an emerging professional Conservation Partner, whose early experiences led her to this career path and her important work to save plants. From agricultural seeds to endangered wetland plants, Alexandra steadily built the skills she uses in her work today. We greatly appreciate her dedication to research on alpine plants, and her collections that contribute to our knowledge of seed longevity – not to mention her optimism and passion!

When did you first fall in love with plants?

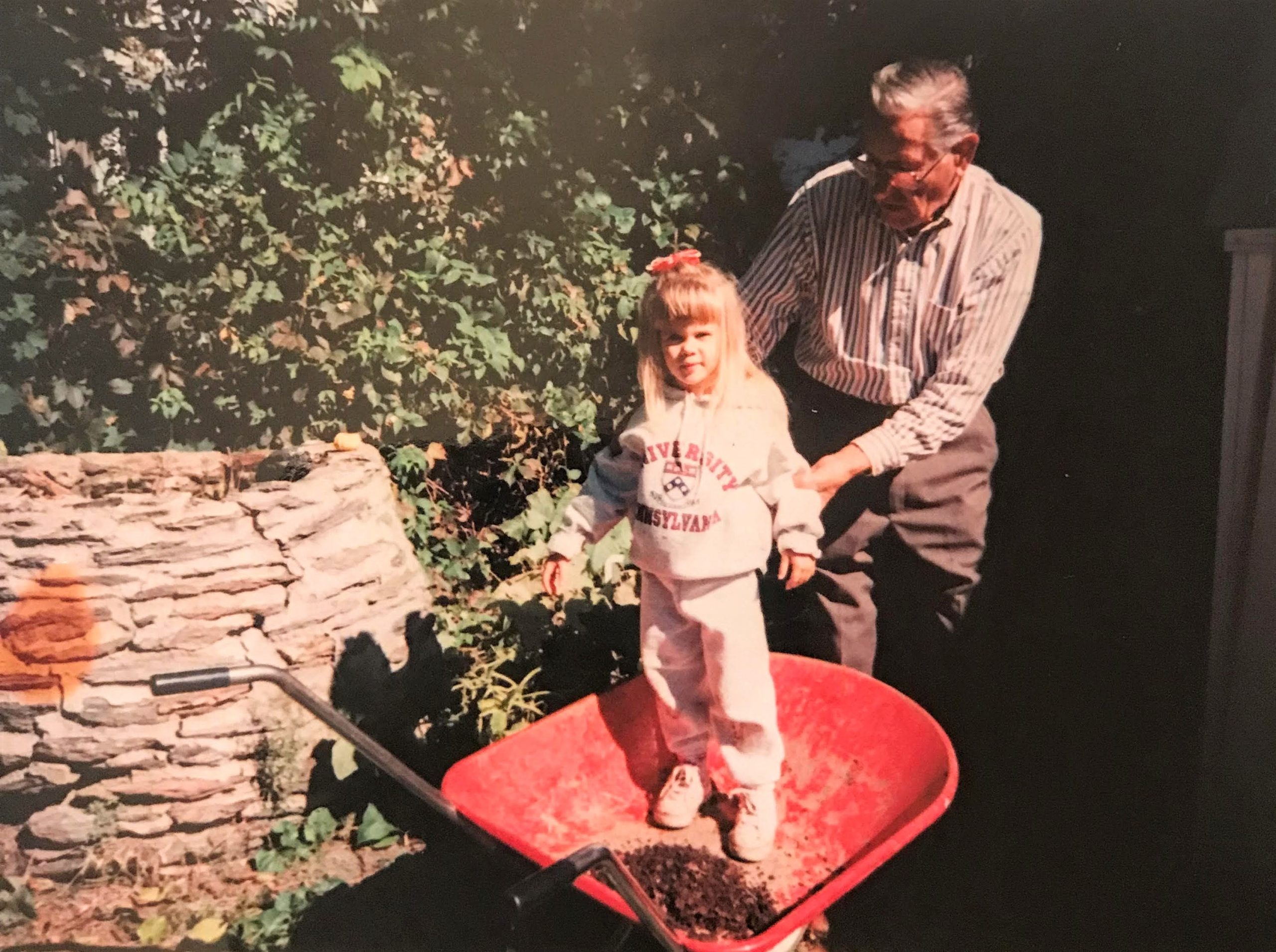

Growing up, I was always drawn to animals. In large part, this had to do with the comfort they provided – as a shy child, it was easy for me to talk to and display emotion around them. But thinking back to those younger years, even though I may not have realized it at the time, I also felt drawn to plants. I am typically not great at remembering specific events from my childhood, but I have such vivid memories of playing inside a large shrub in our front yard, the bright yellow flowers of the forsythia lining the fence, and lying under a majestic willow, admiring how the flowing branches swayed in the breeze. However, it wasn’t until college – during field trips in the woods of central Pennsylvania with my enthusiastic botany professor – that I started seeing plants as fascinating and complex organisms. And that is when the love truly blossomed.

What was your career path to Denver Botanic Gardens?

In college I majored in Biology and minored in German. These two seemingly disparate interests led me to an internship at BASF in Germany, where I worked in an agricultural seed lab. Working in a different country was a great experience, but I knew my passion didn’t lie in working for a large corporation. Returning to Pennsylvania, I explored opportunities to work with native plants and got a position as the Plant Protection intern at Morris Arboretum. The internship title more literally meant integrated pest management (an important piece of keeping living collections alive and healthy), but I took it to mean more than just that. Through an independent project on an endangered, diminutive wetland species, I learned about rare plant conservation and what it means to protect plants in other ways. I went on to receive my master’s degree in Plant Biology and Conservation from Northwestern University and Chicago Botanic Garden, where I researched the seed ecology of southwestern forb species. Working and studying at two public gardens solidified my interest in research and plant conservation at botanic gardens. Perhaps by fate, a seed conservation position opened at Denver Botanic Gardens just as I was finishing my thesis. Next month marks five years since I started working at the Gardens.

In your experience, what are some of the pressing conservation needs related to Colorado’s rare and native plants?

Wildfires, drought, and warmer temperatures are becoming the norm in Colorado, and the plants already considered rare or threatened will face challenges at a graver scale. Seed banking allows us to have an insurance policy in case of population destruction or extinction. However, we can’t collect seeds and put them into storage haphazardly – we need to have a plan for viability testing, recollection, and storage longevity studies to ensure we have a viable collection for a reintroduction or restoration project. Oil and gas development is also a major threat to the rare and native plants of Colorado. In these cases, in-situ protection measures are primarily needed.

The Colorado Natural Heritage Program has been working on a cool and important project to create species distribution models for Colorado’s Plants of Greatest Conservation Need. These models identify potential occurrences for the species. Organizations and volunteers can then go out and look in these areas to ensure we have accurate population information for species of concern.

What are some of your current projects at Denver Botanic Gardens? What successes or challenges have you encountered in your work?

Last summer I set up an open top chamber warming experiment in the alpine region of Colorado to study the effects of increased temperature on two rare species, Avery peak twinpod (Physaria alpina) and Weber’s saw-wort (Saussurea weberi). Although I encountered some challenges with the setup of the chambers, I am hoping to get things more secured this summer and continue the project with just P. alpina. I’m also planning a germination experiment in the lab to understand how increased temperatures affect germination requirements and growth of a few rare alpine species. Before the pandemic, I conducted an accelerated seed longevity experiment and found that Colorado alpine species may be short-lived in ex situ seed banks. I am particularly interested in how rare alpine species will respond to climate change and conservation measures we can put in place. This research contributes to the North American Botanic Garden Strategy for Alpine Plant Conservation, which was recently published by Denver Botanic Gardens and Betty Ford Alpine Garden.

Please share more about how you are contributing to CPC’s IMLS-funded seed longevity study.

First, I identified old seed collections that we have at the Gardens that would work for the project. Once the species/accessions were finalized, I used element occurrence records from the Colorado Natural Heritage Program to locate the historical source populations of the collections. Last summer, I scouted three of the five populations and was able to make seed collections from two of them. Those seeds were sent to NLGRP to be tested against the historical collections. I will target the other three populations this field season. It’s a really cool project and I’m excited to see the results!

What advice do you have for newcomers to the field of plant conservation?

I know that I can sometimes get discouraged about plant conservation when thinking about climate change, political barriers, and public apathy. But it is important to remember that the work of plant conservation is so important, and every person working in the field has something to contribute to help protect our threatened plants. There can be challenges and disappointment, but every day can also offer new and exciting information. One of the most important things is to stay optimistic and passionate!

What has it meant to you to be a member of the CPC network? How has CPC supported your work?

My first CPC conference was in 2019 at the Chicago Botanic Garden, where I saw firsthand the closeness among members and the amazing work that folks are doing with rare plants. That was also the year that the Rare Plant Academy was introduced to the network, which I think is such a great resource to connect members of CPC. I’m excited for the annual meeting this May and to see folks in person again!

As one of the first partnering institutions with the CPC, Denver Botanic Gardens has received funding and support for seed collection and conservation for some time. All my work in seed conservation is directly supported by CPC.

What advice would you give to the public who want to learn more about how they can help save imperiled plant species?

I think the first step would be to gain knowledge on the imperiled or threatened plants in your region and spread that knowledge to others. Many institutions have various outreach or volunteer events that may contribute to that knowledge. Find your local organizations that are working with native plants, and sign up for newsletters or follow them on social media to stay up to date on opportunities. I’m perhaps a little biased, but visiting a botanic garden is also a great way to learn more. So many people don’t realize that botanic gardens have research or conservation departments that are working directly with imperiled plant species.