Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

August 2019 Newsletter

Islands are indeed paradise.

These remarkably special places have all of the allure and romance we often imagine, but are also incredibly challenged in the face of a rapidly changing world. In this month’s Save Plants newsletter, we focus on the rare plants under threat on islands and highlight the incredible efforts of those working to save them.

Islands have the dubious distinction of being both hotbeds for species diversity as well as being epicenters of extinction. Island plants are unique and have oftentimes evolved without outside threats and, in many cases, have lost their defenses that mainland counterparts share. In this way, island plants are unprepared for invasive species and disease as well as the disruption brought about by colonization, exploration and land use. All of these threats, of course, are caused or exacerbated by humans.

But lucky for islands, It’s not just the plants that are unique here – those hardworking conservationists that live and work on islands are a special breed as well. And I should know – I got to know many of these conservationists as I completed my dissertation work on plants in the Pacific islands. I’ve found that island conservation biologists are some of the most passionate and hard working off all those toiling to save species. A high fortitude is needed to persevere in these conditions where terrain is daunting, resources scarce and time limited. But despite the challenges, the rewards are great and successes are being had in these deceptively beautiful places.

Read on to learn more about those who refuse to let paradise be lost.

Building a Flora on the Vineyard

The island of Martha’s Vineyard, which lies five miles off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, is many things to many people: a place of magical beauty, a historical landscape, an environmental habitat, a summer vacation spot, a year-round home. And, despite being subject to wide-scale deforestation several times since European settlement in 1602, it is home to habitats rich in biodiversity – a fact that speaks to the resiliency of nature. In particular, the scrub oak (Quercus ilicifolia) dominated frost bottoms (unique pockets of habitat prone to frost) and outwash plains sustain globally rare moths and butterflies, and several rare plants. The island even supports the rarest ecosystem found in Massachusetts: sand plain grasslands, a system that supports a high concentration of rare plants. Yet, the rich flora of the island is understudied.

An understanding of what plant species are present and where they are found, as learned through a floristic survey, provides a foundation for plant conservation work. The original flora of Martha’s Vineyard was published in 1997 by Debra Swanson and Carol Knapp (PHA’s first research associate, serving from 2001-2005). With the appointment of botanist Mellissa Cullina as research associate in 2001, Cullina and Executive Director, Tim Boland, conducted a five-year herbarium voucher study at the New England Botanical Club (NEBC) herbarium at Harvard University examining the historical collections of Martha’s Vineyard. This laid the groundwork for the vouchered based flora in progress today!

Thus, in 2013, Polly Hill Arboretum (PHA) began a floristic study program, called ConServator, that allows their staff, research associates and volunteers, as well as many conservation partners throughout the island to contribute data via a web-based geographic information system (GIS). The software program, a cloud-based platform, called ArcGIS Online, is augmented by a customized program designed by PHA that allows multiple conservation organizations on Martha’s Vineyard to record and map plant locations and additional data in the field.

To date, the ConServator program has enabled the mapping of nearly 1,200 plant locations, and associated each location with a herbarium voucher and associated data. PHA will use the data collected to create a modern flora of Martha’s Vineyard and the adjacent islands. The conservation groups collaborating with PHA manage close to 14,000 acres of land, and some of the rarest plants are found on the properties they steward. The groups focus on the enumeration of the island’s flora lending itself well to the documentation of rare plants, their protection, or re-introduction when appropriate.

-

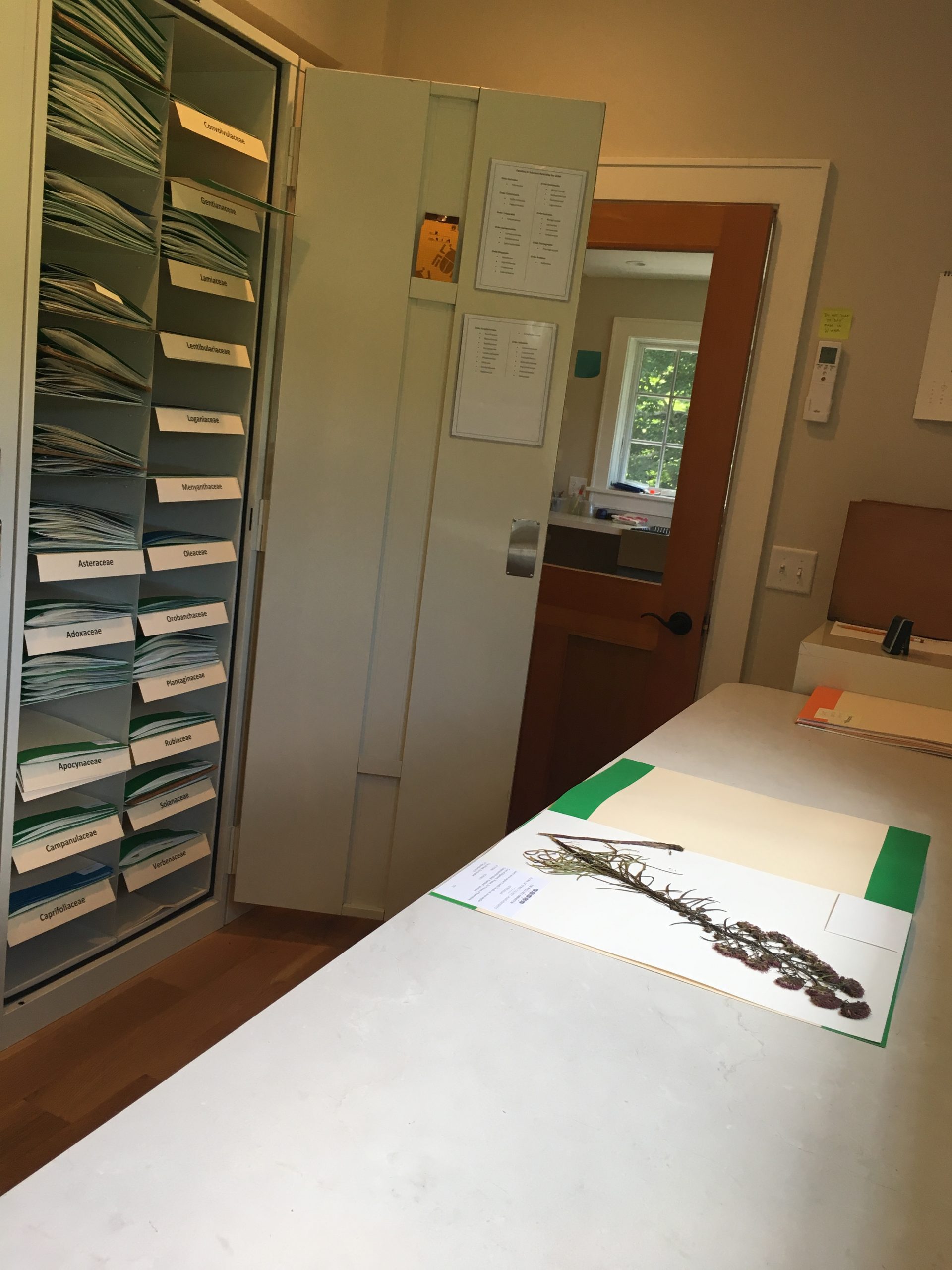

The PHA nursery grows nearly 40 species of native plants for restoration of homeowner use. Here, 1500 New England Blazing Star plugs wait fall planting in the PHA fields. -

A voucher specimen of New England blazing star (Liatris novae-angliae) collected as part of the ConServator project. Herbarium vouchers are important natural history records that capture a species’ presence in a location at a specific time. -

Since 2008 hundreds of locally grown blazing star has been planted in the 4 acres of fields at the Polly Hill Arboretum.

As a result of being able to document the rare plants, an outgrowth of the mapping program has been PHA’s work propagating rare plants in its nursery production facility, and working on restoration projects with local conservation organizations and at the Polly Hill Arboretum. And some of these rare plants certainly need the help. The finite landscape of Martha’s Vineyard is already under developmental pressures for large secondary vacation homes and, or commercial development. The island also supports an extreme density of deer, an estimated 50 per square mile, which threaten rare plants with their browsing. The issue of limited space on the island may only be exacerbated by climate change. Throughout the world, the traumatic effects of climate change are particularly evident on islands. Sea level rise coupled with severe coastal erosion and the omnipresent threat of hurricanes in this region of New England is a great cause for concern.

One of PHA’s earliest efforts was to develop the propagation protocols of the Northern Blazing Star (Liatris scariosa var. novae-angliae). Considered uncommon in New England and a plant of special concern in Massachusetts, it appears in the coastal sandplains where salt-spray, and historic fires have allowed it to persist. On Martha’s Vineyard, it is found on conservation lands and its populations are closely monitored.

Over the last several years, seed collected of Northern Blazing Star was stratified, and grown in PHA’s greenhouse. Hundreds have been planted into the fields at Polly Hill Arboretum both as a conservation measure and as a methodology to look more closely at pollinators.

So much of PHA’s work, including the ConServator program, involves a network of collaborators and their support in obtaining permits, allowing access to rare plants, and growing plants successfully in the nursery facility. It takes a village of talented, dedicated, and visionary conservationists who care about the island’s biological heritage and work to preserve it for future generations. Founder Polly Hill took the long-view and started plants from seed to begin her arboretum at the age of 50 years old. Now the arboretum tries to take the long-view in their conservation work, and the mapping is just step one.

Photos (except where noted) by Tim Boland, courtesy of Polly Hill Arboretum.

Community Collections for ‘Ōhi‘a

If you are not from Hawai‘i, you may not have heard of ‘ōhi‘a. If you are from Hawai‘i, you have almost certainly heard of or seen these forest trees in some form. Featured in hundreds of mele and ‘oli (traditional songs and chants), they are also used in lei, hula, and other traditions. The strong wood is used for building, and is a physical embodiment of the Hawaiian god Kū. Just as ‘ōhi‘a is integral to the Hawaiian culture, the various species of ‘ōhi‘a (Metrosideros polymorpha and closely related species) are critical to Hawaiian ecosystems, providing food and habitat for native animals and understory plants, and services like watershed protection to humans. And they are facing a serious, and growing, threat: Rapid ‘Ōhi‘a Death, or ROD.

Rapid ‘Ōhi‘a Death is caused by two wood-dwelling fungi, Ceratocystis lukuohia and C. huliohia. These fungi were new to science and recently described. The more virulent of the two, C. lukuohia, is new to Hawai‘i, as evidenced by its unprecedented destructive and rapid spread. Being on islands makes the native flora especially vulnerable to invasive pathogens that disturb the natural balance of ecosystems, which evolved in isolation for millions of years. Unfortunately, these fungi can be spread both by wind and by human mediated movement, making them not only pathogens that wreak havoc on islands, but ones that are moving quickly.

Rapid ‘Ōhi‘a Death is considered a crisis. Fortunately, a large interisland, interagency team of collaborators is working to address the many aspects of the threat of ROD, including pathology, ecology, and other scientific research, rapid response planning and implementation, monitoring, education, and a massive outreach campaign to help slow the spread. Lyon Arboretum, a founding member of the Hawai‘i Seed Bank Partnership, is taking the lead on banking seeds of the various species of ‘ōhi‘a.

The Rapid ‘Ōhi‘a Death (ROD) Seed Banking Initiative seeks to preserve the natural genetic diversity of ‘ōhi‘a. The initiative coordinates the systematic collection of seeds from across seed zones on each island, and stores the collections in seed banks for future restoration and disease-resistance testing. Working with nine varieties of Metrosideros polymorpha, two varieties of M. waialealae, M. macropus, M. rugosa, and M. tremuloides – all of which are endemic to the Hawaiian Islands, and across the multiple islands being impacted by ROD means that this effort is no simple task.

-

The workshops Marian has led throughout Hawai’i have brought community members and conservation practitioners together to help save ‘Ōhi‘a. Photo credit: J.B. Friday, courtesy of the University of Hawaii, Mānoa. -

Seeds of ‘Ōhi‘a (Metrosideros polymorpha var. pumila) on Moloka’i, ready for collection. -

Lyon Arboretum Seed Bank Manager, Marian Chau, Ph.D., makes a seed collection from Metrosideros polymorpha var. polymorpha on O’ahu, while sporting a shirt that shares her love for these culturally important trees.

Collaboration is essential in this project, as there is so much work to be done. The Hawai‘i Seed Bank Partnership has been critical for banking seeds locally on each island and backing up collections within islands. In addition to Lyon Arboretum (O‘ahu), the primary partners are Hawai‘i Island Seed Bank, Ulu Lehulehu Seed Bank (Hawai‘i Island), Maui Nui Botanical Garden (Maui), U.S. Army Natural Resources Program (O‘ahu), National Tropical Botanical Garden (Kaua‘i), and Kaua‘i Division of Forestry & Wildlife. However, these seed banks cannot do all of the necessary seed collecting without help from the broader community. For the Seed Conservation Laboratoy Manager at Lyon Arboretum, Marian Chau, Ph.D., outreach training has been one of the best parts of the project.

Marian has led 28 Ōhi‘a Seed Conservation Workshops statewide. Across five islands, over 500 people have been trained to identify different types of ‘ōhi‘a, collect the seeds, and prepare them for submission to the seed banks. Provided free of charge, thanks to generous funders, this has allowed Marian and partners to open the workshops broadly to the local community. Many participants have been people who already work in conservation, but many others have been concerned citizens who just want to help. The rich cultural connections to native plants have created a deeply rooted tradition of stewardship in Hawai‘i, and so hula and other cultural practitioners, teachers, hikers, tour operators, and many more have become involved. “It is always exciting to open people’s eyes to the wonder of seeds, especially if they have never seen ‘ōhi‘a seeds before. This has been such a rewarding outreach effort, seeing how folks from so many walks of life care deeply about our ‘aina (land/earth) and want to help save ‘ōhi‘a,” Marian states.

The public’s engagement with the project has been empowering. People have many reasons for caring about their natural world, and most folks would really love to help, but they do not always know how or where to start. When given options, some people want to get in the field to collect seeds and personally connect with the plants, while some are fascinated by the science and want to help process the seeds in the lab. Some want to provide community venues or materials or local networking assistance, while some want to donate money to support these efforts. Some want to do all of the above. The public’s response has served as proof that in Hawaiian culture, the natural world is a direct extension of ‘ohana (family). With Marian and the rest of Lyon Arboretum, many amazing partners, and the community all as family, the ‘ōhi‘a and the forests they create have a chance of weathering the ROD crisis.

Photos (except where noted) by Marian Chau, courtesy of the Lyon Arboretum.

Strength in Numbers: Working Together to Understand, Protect, and Restore the Rare Plants of California’s Channel Islands

California’s Channel Islands have been described as the Galapagos of North America. Situated across the Santa Barbara Channel from mainland California, the eight-island archipelago supports a rich diversity of flora and fauna. More than 10% of the islands’ flora (>100 taxa) are endemic to the Channel Islands – that is, they are found nowhere else. Dozens of endemic animal species also call the islands home.

Unfortunately, the islands were subjected to nearly two centuries of human-caused disturbance, which led to the extinction of some species and threatened the persistence of others. Perhaps most notable were the impacts from introduced animals such as cattle, deer, pigs and sheep, whose grazing and trampling dramatically altered the landscapes of the islands. Fortunately, these herbivores have been removed from all but one island over the last few decades and the islands’ landscapes are in a period of recovery. Some plants are rebounding more quickly than others, but the overall positive trajectory of the archipelago as a whole has created an opportunity to update the status of rare plants on the islands and to implement recovery actions to help bolster their numbers and increase their resiliency. Our team at the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden and our partners are working hard to take advantage of this opportunity.

Spring 2019 marked the inauguration of an ambitious project designed to advance the conservation and recovery of 14 listed plants on seven of the eight California Channel Islands. With funding from the US Fish & Wildlife Service’s Section 6 grant program, a team led by the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden and comprised of island owner/managers (the Catalina Island Conservancy, Channel Islands National Park, The Nature Conservancy and the US Navy) and conservation and research organizations (California Institute of Environmental Studies, the US Geological Survey and Wildlands Conservation Science), set out to relocate historic populations of rare plants and to begin implementing recovery actions for these imperiled plants. The size of the collaboration gives us the strength in numbers needed to think and act big. Over the next three years, we will conduct surveys and monitor known populations; make conservation seed collections; conduct research; propagate plants from seeds and cuttings; and implement seeding and outplanting projects on the islands. Survey and monitoring data will provide valuable information for updating the status of each species, while the other actions are designed to advance their conservation and recovery.

To achieve such ambitious goals on a short timeline, we needed to think outside of the box and utilize innovative tools and novel approaches to surveys and mapping. This meant developing and adopting a new, standardized protocol for all rare plant surveys across the archipelago and employing a helicopter to increase the efficiency of our surveys. The helicopter not only allowed us to cut down on driving and hiking time, but it also provided the opportunity to scout for our focal species (and potential habitat) aerially while en route to the next drop-off point. In May, a subset of the collaborative group including our team from the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, as well as The Nature Conservancy and Wildlands Conservation Science, spent several days on Santa Cruz Island revisiting, surveying, and mapping historic populations of four focal plants: island barberry, Hoffmann’s rockcress, island rush-rose, and Santa Cruz island cliff aster (Berberis pinnata ssp. insularis, Boechera hoffmannii, Crocanthemum greenei and Malacothrix indecora). In July, traveling on foot over four days, we mapped Santa Cruz Island dudleya (Dudleya nesiotica). Concurrent with both efforts, we made conservation seed collections and collected tissue samples for genetics studies. Meanwhile, other partners were conducting surveys, collecting seeds and outplanting island-grown plants on Santa Barbara, San Miguel, and Santa Rosa Islands.

The abundant rains and long, cool spring of 2018/2019 created the perfect conditions for finding rare plants on the islands – coaxing seeds to germinate en masse and allowing flowers to persist for longer than usual. All told, our collective effort resulted in the doubling of known populations for some species and an increase in numbers by an order of magnitude for others. The information we gathered this year has changed our understanding of where some of these plants grow and redefined where we will look for them in the future, as we found them occupying new areas of the islands and in habitat types with which they were not previously associated. As the season winds down, we’re turning our attention to seed cleaning and curation, data management, and preparing for nursery propagation. Over the next two years, we will gain insights into propagation and outplanting methods for these species as we work toward improving resiliency and redundancy across the islands.

While three years will not be enough to fully recover any one of the rare plants tackled with this grant, this collective effort will go a long way in providing data to state and federal agencies while also laying the groundwork for further conservation and restoration efforts. Channel Islands National Park has already doubled down on this work by awarding three additional years of funding for follow-up surveys, seed collections, and restoration maintenance. By working together across multiple islands, we’re able to give these rare plants a big push forward and help them gain much needed ground on their path to recovery. When it comes to conservation, we are undoubtedly stronger in numbers.

-

Island rush-rose (Crocanthemum greenei) is a federally threatened shrub that is endemic to the Channel Islands. -

Santa Cruz Island is the largest and most diverse of the Channel Islands, with habitats ranging from coastal terraces to native shrublands to pine forests. -

Santa Cruz Island cliff aster (Malacothrix indecora) is a federally endangered annual with an affinity for coastal habitat.

All photos by Heather Schneider, courtesy of Santa Barbara Botanic Garden.

Jennifer Possley

Working in the subtropics at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden means that Jennifer Possley has given plenty of blood and sweat to save rare plants. Her multiple talents as an observant naturalist, GIS specialist, careful scientist, brilliant photographer, not to mention her congenial personality, have made her an invaluable leader helping to preserve endangered plants in the natural areas of South Florida and the Caribbean Islands.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

It happened gradually! Growing up in Michigan on 20 acres of woods and wetland, I was always surrounded by plants, and my parents both had an affinity for plants. But that was just background to me. I majored in biology at Kalamazoo College, but I didn’t even take Botany. When I began a master’s program in Agronomy at University of Florida (UF), a love of plants started to creep up on me. By my second year, I was taking as many botany courses as my major allowed, and I really enjoyed them. Former UF botany professor Dr. Walter Judd deserves much of the credit for igniting my love of plants.

What was your path to becoming the South Florida Conservation Program Manager?

My first job after completing my master’s degree was at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Miami. I was hired as a field biologist, with six months of funding. I didn’t imagine I would stay very long. Over time, I came to adore the flora of South Florida and especially the tiny urban preserves in Miami-Dade County. I had excellent training for well over a decade, working under the guidance of Dr. Joyce Maschinski. When she left to join the CPC, I became the program manager.

What about working with plants has surprised you?

It’s been a nice surprise how many friends I have made through working with plants—locally and around the world. If you have an affinity for a plant group (like me with ferns), the other enthusiasts are a small community of instant friends whom you might visit when you travel or collaborate with on new projects. Even if you don’t speak the same language, you can at least speak botanical Latin to each other!

What are some of the threats to rare plants and challenges to plant conservation in South Florida? How have your program’s efforts met those challenges?

Well, to name a few: extreme habitat loss, sea level rise, a plethora of invasive species, inadequate funding, inadequate legal protection for rare plants, public apathy, rapid population growth, and a transient population. I think one of the things that helps us at Fairchild to meet these challenges is our staying power. We’ve had low staff turnover, good recordkeeping, and therefore good institutional memory. Our program adapts and improves over time. Also critical to our efforts has been strong, longstanding, and collaborative partnerships with land managers and biologists throughout our region. That makes our work more enjoyable as well!

Please share one of your conservation projects and how what you’ve learned could benefit others working to conserve rare plants.

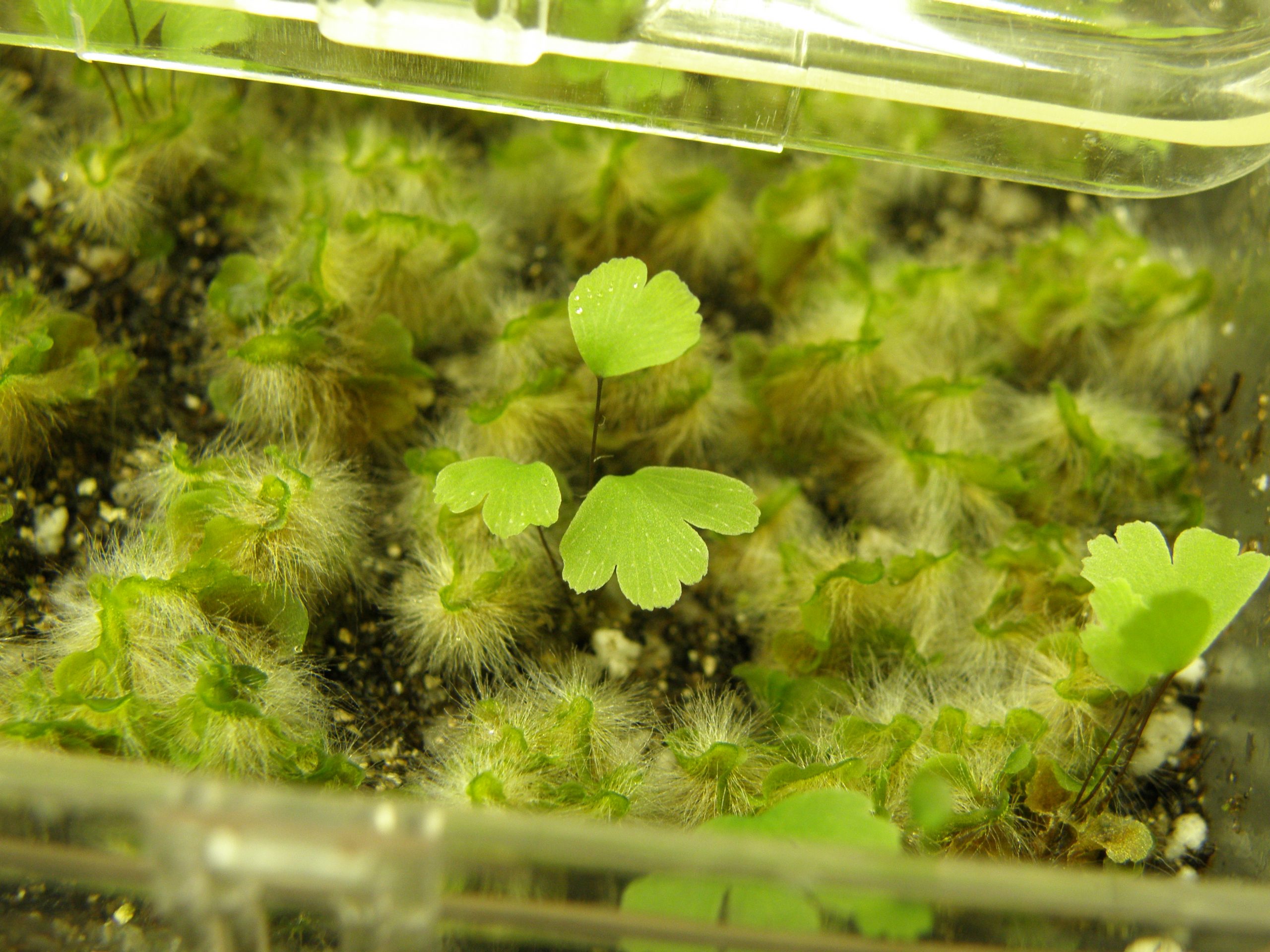

When I first arrived in South Florida, there were not very many people working to conserve the region’s ferns, despite the presence of dozens of rare fern species. Over time, and without really intending to, we built a comprehensive fern conservation program at Fairchild. We collect spores, propagate ferns from spore, and conduct augmentations and reintroductions where populations are shrinking. Guidance from colleagues within Fairchild as well as at CREW (the Center for Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife at Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Gardens) and the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation (USDA-ARS) has helped to fine-tune the program. We have a beautiful and diverse living collections of ferns of South Florida and the Caribbean, which I love to show off to visitors. More than perhaps any other types of plants, ferns may look drastically distinct during different parts of their life cycle. Even young sporophytes may look quite different from mature ones. Actually, growing the ferns myself and learning to identify them at all of their life stages has really helped to inform my field work and is also one of my favorite parts of my job.

What has been the most challenging aspect of your work?

That’s a tough question, but certainly one challenge has been finding a balance between doing plant conservation work versus interpreting our work to the public. I have been a biologist at the same botanic garden for more than 18 years now, and education and outreach has become a bigger part of my job every year. But I don’t resent that aspect of my work; I think that reaching outside of our plant conservation bubble is increasingly necessary. Everyone should understand why plant conservation is important to our planet and to ourselves.

What emerging research or conservation trends for plants do you find most exciting?

I’m happy about all the ways in which smartphones make our jobs easier. So many new apps can help us to save time and be more effective. One of my team members just downloaded “HabitApp” (only available for Android so far), which we intend to use to estimate canopy cover above recently reintroduced endangered plants. I’m excited to not burn my retinas on a mirrored densiometer (hand-held tool to visually estimate canopy cover) anymore, and to have data that will be quicker to obtain and easier to repeat. I also have been getting into iNaturalist and enjoying that. I use the app to identify insects and mushrooms, and I help others out by identifying ferns.

-

Jennifer’s early forays into conservation included working in the national AmeriCorps volunteer program, 1997. -

Carter’s orchid (Basiphyllaea corallicola), a rare orchid Jennifer has monitored in South Florida, seeing it move from a few struggling individuals to two stable populations. Photo credit: Jennifer Possley, courtesy of Fairchild Botanical Garden. -

Jennifer is willing to lay all out for plants – here monitoring ferns from a precarious perch. Photo credit: Courtesy of Fairchild Botanical Garden.

-

Juveniles of the rare holly leaf fern (Lomariopsis kunzeana) are often found around holes, and not uncommonly accompanied by large spider webs. -

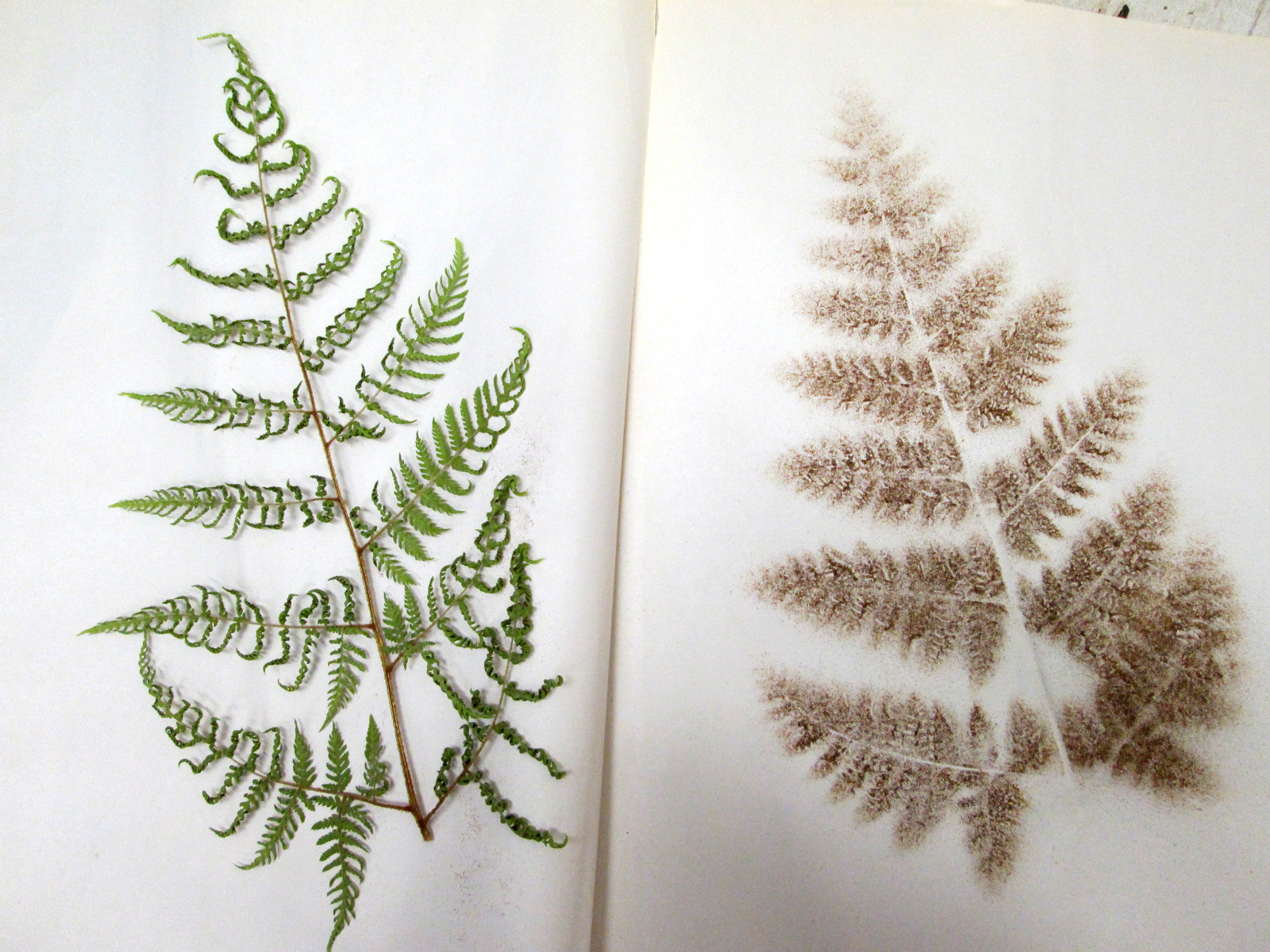

Ctenitis sloanei ex situ spore print. Photo credit: Courtesy of Fairchild Botanical Garden. -

Silver dollar fern (Adiantum peruvianum) puts on vegetative growth while in a growth box. Photo credit: Courtesy of Fairchild Botanical Garden.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today