Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

April 2020 Newsletter

During this unprecedented time of sequestration and working from our homes, it is abundantly clear how interconnected we all are – interconnected to one another and the natural world. Now more than ever, we can appreciate a healthy world, a resilient world. We can appreciate that plants are key and we know that they still need our help… not only here in continental North America, but also in the U.S. territories.

The important research and conservation actions featured this month focus on plants that do not produce flowers. No less beautiful, no less interesting, these plants have benefited from long-term dedication and study by our Participating Institutions. We are pleased to showcase this exceptional work and the people who make it happen.

We wish you and your families good health. Please stay safe!

Joyce Maschinski

CPC President & CEOBeautiful, intricate, or otherwise striking, flowers are one way plant conservationists draw attention to their cause. These splashes of color and unique forms are, in some ways, our answer to the charismatic megafauna that captivate the public. But while flowering plants are the largest group of plants, they are not representative of plants as a whole. In the next couple of newsletters, we will explore some of the non-flowering plants our Participating Institutions work on to understand and protect.

In this issue we explore the non-flowering vascular plants – these are the plants that most everyone would recognize immediately as plants: they have true roots and stems as well as vascular tissue. Some are more familiar than others. Conifers are well known trees in many parts of the U.S.; their evergreen foliage and cones of various sizes are familiar. But cycads, sometimes mistaken for palms, are another cone-producing group of plants found in the southeastern U.S. and in various places around the world. Both conifers and cycads, along with divisions of plants, are gymnosperms – producing seeds that are “naked” in that they are not wrapped in an ovule like those of flowering plants. Ferns are another large group of non-flowering vascular plants familiar to many. Unlike gymnosperms, they do not even produce seed. Instead, they release spores that grow into a free-living gametophyte (a part of the plant life cycle with half the chromosomes, and typically attached to and dependent on the sporophyte ‘adult’ plant in seed producers).

Ferns and gymnosperms once dominated the earth. In the times of dinosaurs, tree ferns and cycads were abundant and diverse. The appearance of those domineering flowering plants didn’t occur until the Triassic or Jurassic period, but they quickly took over. Though not as dominant as they once were, the non-flowering plants are an important part of our modern ecosystem and have their own unique beauty even without flowers trying to steal the show. Learn more about some of the non-flowering plants in the National Collection and what CPC’s Participating Institutions are doing to protect them in the stories below.

Saving Micronesian Cycad with Vital Collections

Micronesian cycad (Cycas micronesica), or fadang as it is sometimes called on Guam, is a large tree-like cycad native to the Micronesian islands of Guam, Rota, Palau, and Yap. The impressive cycad with sturdy green fronds was once extremely common on the island of Guam, and even the most common tree in many parts of the forest. However, this began to change in 2003 with the arrival, via horticultural imports, of the invasive insect pest Cycad Aulacaspis Scale, or CAS (Aulacaspis yasumatsui). The impact of this insect has been devastating.

CAS attacks cycads belonging to the genus Cycas by feeding on its sap. This diminutive insect congregates in enormous numbers, forming large white masses visible on the plants leaves, stems, and roots. The pest progressively weakens individual plants, causing them to deplete their energy stores while under stress, which eventually leads to their death. Being an introduced insect with no natural enemy present on the island, the microscopic scale insect was able to rapidly colonize the island, and by 2007 had spread to all native populations of the cycad in Guam and had recently made its way to the nearby island of Rota.

The scale completely eliminated seedling recruitment in all the cycad populations it colonized and weakened plants so badly in the most affected populations that cones were not being produced and reproduction had stopped altogether. Efforts at biological control attempted in Guam were insufficiently effective, and the situation was dire. Realizing the urgency of the situation, Thomas Marler of the University of Guam approached Montgomery Botanical Center (MBC) to conduct joint collaborative fieldwork to collect genetic samples and secure germplasm (living tissue that can be used to grow individuals, such as seeds, seedlings, or offsets for ex situ conservation).

As a conservation, research, and education facility emphasizing palms and cycads, MBC was fully onboard. In 2007, MBC sampled DNA from all known cycad populations on both Guam and Rota and collected seeds from populations that were still reproductive. After germinating the seeds at MBC’s nursery, some of the resulting seedlings were distributed to other botanic gardens, and others were eventually planted in the field at MBC. New York Botanical Garden led the effort to conduct genetic studies of the species (Cibrián‐Jaramillo et al., 2010) using the samples collected.

Safe from CAS, the plants at MBC have thrived. The garden currently hosts 215 plants of Micronesian cycad in its living collection – grown from seeds collected from a total of 93 separate mother plants sampled across 22 separate wild populations – an impressive collection of the remaining diversity of the Guam and Rota populations. The collection is the largest single-species representation of any cycad at MBC and serves as an important safeguard against the species’ extinction.

The mission of the Montgomery Botanical Center is to advance science, education, conservation, and horticultural knowledge of tropical plants, emphasizing palms and cycads. As such, they have worked to build and maintain conservation collections of 259 cycad taxa. With collections impressively totaling over 7,000 individuals, MBC needs to be strategic about their remaining capacity. The development of MBC’s cycad collection is informed by studying the genetic diversity of wild cycad populations and comparing it with the diversity captured by MBC’s ex situ collection (see “Can a Botanic Garden Cycad Collection Capture the Genetic Diversity in a Wild Population?”, and “Will the Same Ex Situ Protocols Give Similar Results for Closely Related Species?”). These studies have shown that species biology must be considered when developing a collecting strategy, and that the genetic diversity of ex situ collections can best be conserved by managing populations separately, collecting and maintaining multiple accessions, and collecting samples over multiple years (see January 2019 Newsletter). As shown by recent collaborative research in collections genetics by several institutions, the combined holdings of a group of collections can be leveraged cooperatively as a metacollection to advance conservation and research.

This valuable Micronesian cycad collection exemplifies how MBC contributes to the conservation of cycads: by developing population-based collections of high scientific and conservation value, propagating these collections, and promoting the advancement of knowledge about cycads by making these collections available to students and researchers.

The ground collection of Micronesian cycad at MBC is now largely reproductive, and numerous seeds have been produced via hand-pollination for distribution to other gardens and to cycad horticulturalists. Most importantly, seeds produced at MBC have been sent to strengthen the ex-situ collection of the species on the island of Tinian (Northern Marianas), which was established for potential reintroduction of the species to Guam if biological control is ultimately successful. These seeds are of critical importance. The Tinian collection can no longer be strengthened with wild-collected seeds because they are no longer being produced in native populations due to the devastation caused by CAS.

The living collection of this species at MBC, available to students and researchers throughout the world, has greatly advanced our understanding about Micronesian cycad specifically and also about cycads in general. Plants from MBC’s collection have been used in papers covering a broad range of topics, such as phytochemistry, physiology, anatomy, and phylogenetics. Dr. Irene Terry, professor at the University of Utah and MBC Research Fellow, has made extensive use of the collections for pollination biology research. Her studies include topics such as the production of heat and volatiles by C. micronesica cones and possible pollination vectors of open-pollinated cones at the garden.

MBC’s ex situ collection represents the diversity of the wild populations, provides a resource for research to increase understanding of the species, and provides seed to Tinian as potential reintroduction stock. MBC has made sure the populations of Micronesian cycad on Rota and Guam are not without hope.

Searching for Ferns

Ferns abound on the Island of Enchantment – Puerto Rico. The U.S. territory is home to many species of ferns, including 22 endemic species found nowhere else. While stunning tree ferns may capture the attention of island visitors who venture away from the beaches and into the forest, rare endemics are the prize that botanists from Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden have been seeking.

Fairchild staff recently concluded a multi-year project with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), focused on the island’s eight federally listed endemic ferns.

Despite extreme rarity and acute threats, these species had been poorly studied beyond their initial scientific description. In many cases, we don’t even know if their populations still exist. Access and identification present significant challenges. Basic questions remain unanswered, such as whether the species represent valid taxa, distinct and capable of reproduction. To begin addressing some of these issues, staff from Fairchild joined forces with partners from USFWS, the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources, University of Puerto Rico, and the University of Florida to seek out these elusive fern populations. Their goals were to document and quantify occurrences, attempt propagation for the development of ex situ conservation collections, and conduct genetic analyses to determine the phylogenic status of questionable taxa.

These were not quick and simple tasks. Progress towards understanding and conservation was greater for some species than for others. Beginning in 2014, the group made three field surveys to visit or search for seven of these eight taxa – not attempting to visit Thelypteris inabonensis due to its remote locations and the limited timeframe of the trips.

The Fairchild team is well-versed in identifying the native species and ferns in the Miami region. Because the biogeographical roots of many South Florida plants lie in the nearby islands, knowledge of native species in Miami aids in identification of many island species, or at least their close relatives. Team members Jennifer Possley and Jimmy Lange often seek opportunities to use their experience with Miami’s ferns to promote fern conservation throughout the larger region.

Even so, the group struggled with certain taxa. Two surveys failed to find Elaphoglossum serpens in its last known locality (Cerro Punta) – supporting the commonly held belief that this occurrence, like the type locality, was extirpated (completely wiped out) during the construction of a cell-tower. Efforts to make collections of Thelypteris yaucoensis also came up dry, in part due to difficulty in distinguishing this endemic fern from other taxa in the Goniopteris group of Thelypteridaceae.

Field collections were more fruitful for Adiantum vivesii, Tectaria estremerana, and Thelypteris verecunda. Field surveys for these three ferns were followed by genetic studies led by Dr. Emily Sessa and graduate student Lindsey Riibe at the University of Florida. The studies were designed to advance understanding of the very complicated relationships between these rare taxa and their more common relatives. Results suggest that all three of the taxa are of hybrid origin. At least one, A. vivesii, is unlikely to be a distinct taxon – when combined with previous research on its lack of reproduction, the team believes there is support for its delisting. Interestingly, sequencing results for other hybrid Adiantum specimens examined in this study revealed that they may in fact be valid polyploidy (having multiple chromosome sets) taxa in need of formal descriptions and subsequent evaluation of conservation status. Further studies into spore morphology and viability are needed to determine whether T. estremerana and T. verecunda are true species and therefore in need of legal protection.

The biggest conservation progress was made with Cyathea dryopteroides and Polystichum calderonense. The field work was simplified by the fact that the species were already familiar to local USFWS and DNER staff, including this month’s Conservation Champion, Omar Monsegur-Rivera. The increased intensity of surveys during this study, however, increased the number of known individuals of several populations, particularly of C. dryopteroides at Cerro Punta which increased from four to at least 55 plants. As a result of this program, both species have now been successfully cultivated at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, and spores have been cryogenically stored at the USDA National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation (NLGRP) in Ft. Collins, Colorado. The sharing of living material among several botanical institutions has further safeguarded germplasm. In addition, some potential reintroduction habitat has been evaluated and described. Recovery actions, such as reintroductions or augmentations, are therefore very possible in the next decade for both C. dryopteroides and P. calderonense.

Fairchild’s nursery is flush with C. dryopteroides and P. calderonense grown from spores collected during early field surveys. Twenty-three C. dryopteroides are happy and healthy in one-gallon pots, often producing sporangia (spore-forming enclosures on the plants) each winter. The garden’s ex situ collection of 90 healthy Polystichum calderonense individuals has spawned hundreds of small sporophytes in germination boxes. Because this abundance far exceeds the available fern-growing space in Fairchild’s nursery, they sent spore boxes to cooperating institutions, five of which are now cultivating P. calderonense in their greenhouses.

The fern project proved to be productive for all the collaborators and for the conservation of Puerto Rico’s special endemic ferns. However, much remains be done. Continued field work was already clearly necessary for many of the species, and the impacts of Hurricane Maria (2017) and other storms present new unknowns. The project also highlights the potential of ex situ collections in fern conservation on the island. Despite the large number of rare and endemic ferns, none had been secured in ex situ collections prior to this project. Now Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden holds living collections, and the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation holds cryogenically-preserved spores that serve as backstops against extinction for these unique ferns.

Three of the federally listed endemic ferns of Puerto Rico the team studied are species of the genera Thelypteris, a group often known as maiden ferns.

Cones and Clones to Save Florida Torreya

Two hundred years ago, the limestone bluffs and ravines of the Apalachicola River in Georgia and the Florida panhandle were dotted with impressive 30- to 60-foot tall Florida torreya (Torreya taxifolia). The yew-like trees were abundant enough to support harvest, with the light but durable yellow wood transformed into fence posts, shingles, planks, and more. Then came the fungal infection. Florida torreya is now North America’s most endangered conifer, with over 98% of the population lost. The remaining trees are shrubby and short, rarely reaching a top height of 20 feet, and, sadly, rarely reproductive.

Signs of the fungal threat, Fusarium torreyae, had caught people’s attention for decades, but the extent of the impact wasn’t made clear until the 1960s and is still not well understood. In 1984, the tree became one of the first listed under the Endangered Species Act. Soon after, the Atlanta Botanical Garden (ABG) became involved in the conservation of the species. ABG has since led both ex situ and in situ efforts – taking a true full-spectrum conservation approach along with other CPC Participating Institutions, botanical institutions, and a variety of private and government partners.

The Atlanta Botanical Garden was one of the first institutions to receive cuttings from the surviving Florida torreya population in the Florida panhandle. More than 30 years later, many of those trees persist in the ABG’s Gainesville Garden. At the 2018 National Meeting, Vice President of Conservation and Research Emily Coffey, Ph.D., stated that it was a primary objective of ABG to coordinate an effort to have cuttings of all the remaining wild individuals represented in botanical collections – ensuring that their genetic diversity is conserved. Ambitious plans were made for collecting cuttings from many of the remaining 407 unrepresented trees in 2018. Unfortunately, Hurricane Michael hit the Florida torreya’s habitat hard. Nevertheless, 290 trees were visited, material was collected from about two-thirds of those, and 100 individuals were successfully rooted and are doing well ex situ. These will join others taken in by one of ABG’s 22 partnering institutions managing this (soon-to-be) comprehensive collection of the rare conifer.

-

Hurricane recovery monitoring involves establishing a plot around focal trees and monitoring vegetation changes. -

After the storm, saw skills proved key to ABG’s torreya conservation program, as the removed debris that imperiled surviving trees. -

Though fallen trees were plentiful following the storm, some of the torreya escaped being crushed, offering the team hope.

If anything, the hurricane reinforced the need for a focused effort on ex situ conservation. Two weeks after the storm, Dr. Coffey conducted a high-level assessment and was astonished by the damage. Heartbroken, she stood at the top of a ravine and found 80-90% of the mature trees gone. But there was also a glimmer of hope. With the crowns of trees strewn everywhere, she scrambled down a steep ravine in search of one of the largest trees documented in the park – and found it alive. This tall, beautiful female torreya had produced one of the first recorded seedlings in more than 20 years. And the seedling was also still standing! A huge grapevine had prevented a large sycamore from falling directly on the female torreya. It was a very precarious situation, requiring hours of careful planning and saw work to prevent the sycamore from crushing the torreya. “In the end, we were able to save the tree and leave renewed and filled with hope that we would be able to save more trees, and that not all of the individuals had been lost,” Dr. Coffey recalls. “It gave us great resolve and hope, which is what we continue to thrive on.”

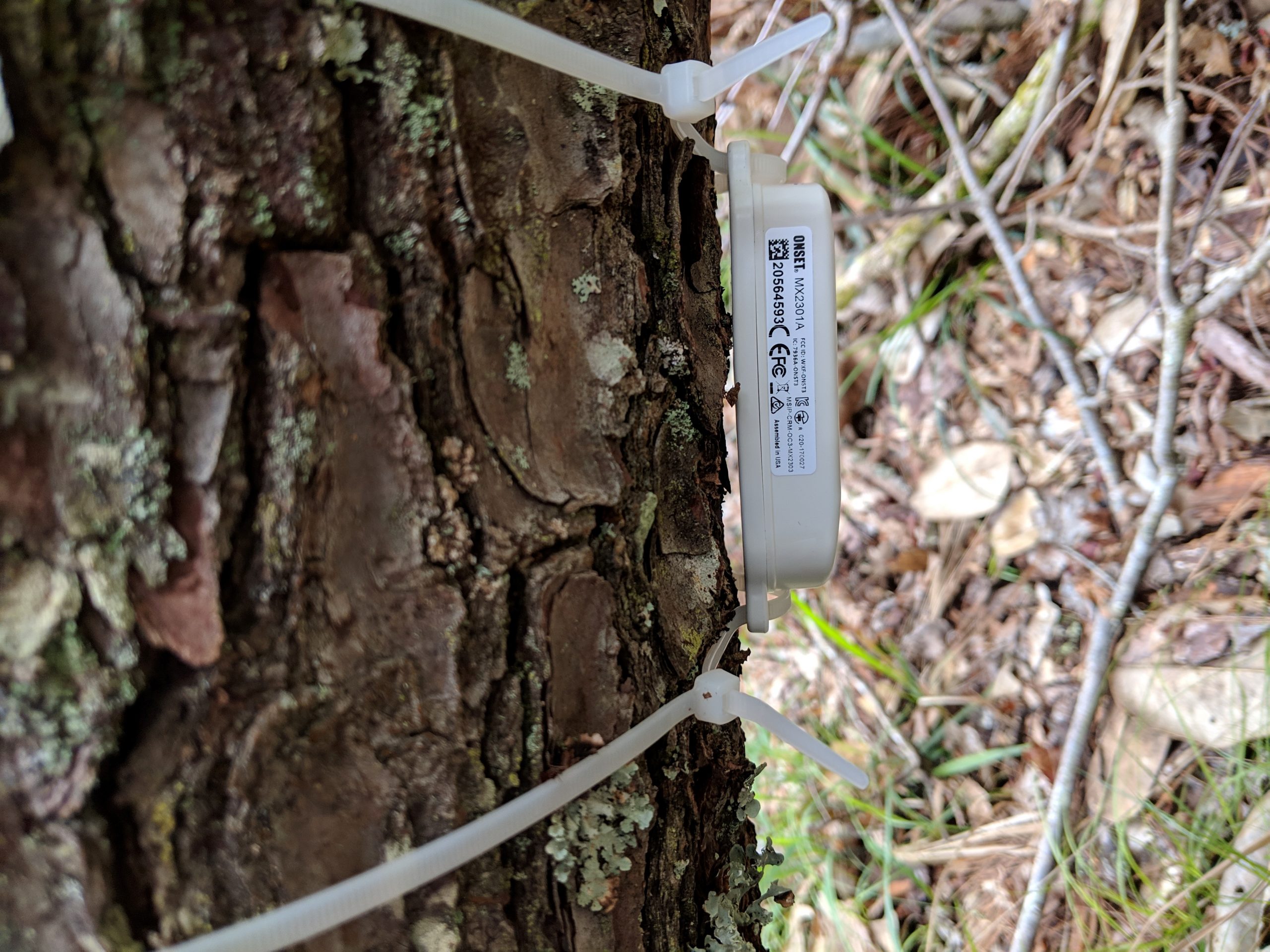

In 2019, adding to its conservation efforts, the Atlanta Botanical Garden team initiated longitudinal tracking of the Torreya population’s response to the unprecedented habitat changes resulting from Hurricane Michael. Forty trees were selected for long-term monitoring for the next five years or more. In permanent plots established around each tree, vegetation will be measured by people and drones, and data loggers will help track key environmental factors. ABG will assess how T. taxifolia responds to the changes across the native habitat as it recovers. Long-term monitoring is a rare yet important data collection method. The results from this work will inform future management efforts and can be used to model population changes following Hurricane Michael.

-

Long-term monitoring is an important part of conservation work and the team hopes to learn a lot about the tree’s needs from this data set. -

Impacted by a fungal infection, many of the Torreya in the wild are short and shrubby. -

Few Florida torreya trees are producing cones in the wild. Many of the seeds the ABG team uses for conservation work come from their grove grown from cuttings.

However, the main threat to the species continues to be the fungal infection. It has killed trees, reduced others to small shrubs, and stunted reproduction. Unfortunately, there have been no advances in controlling Fusarium torreyae. However, ABG has integrated information from a set of experiments testing the susceptibility of other conifers to the fungus. The studies were carried out by Aaron Trulock, a past master’s student at the University of Florida, who found that multiple species of Torreya and a number of species in the southern Appalachians are susceptible to the fungus. This information has given the team caution in their ex situ conservation activities in northern Georgia, especially when choosing sites to continue growth of cuttings from wild plants. It also adds to concerns regarding potential effects of translocation of the species on the spread of the fungus. Some Florida torreya supporters are keen to help the species by relocating the trees or seedlings into the Appalachian Mountains. The garden is working hard to avoid the spread of the fusarium into the Appalachian wilderness.

With the fungal infection still a concern, full recovery of Florida torreya is still a long way off. Atlanta Botanical Garden’s recent work and efforts demonstrate that, as a conservation community, we can work collectively to find creative and new ways to address old problems. “I think in all of our conservation work finding allies is key. It is hard work, but if we can work collectively we can accomplish great things,” states Dr. Coffey. Florida torreya faces significant challenges. With the efforts of dedicated conservationists, such as those at Atlanta Botanical Garden and its partners, this unique conifer is receiving much-needed support to survive for generations to come.

Thanks to the many Torreya partners including USFWS, Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Torreya State Park, Florida Native Plant Society, Torreya Keepers, Jacksonville Zoo and Botanic Garden, Oak Hill Foundation, partnering CPC gardens with ex situ collections, Georgia Plant Conservation Alliance, and the University of Florida, Gainesville.

All photos courtesy of Atlanta Botanical Garden.

Omar Monsegur-Rivera

The Isle of Enchantment has many treasures. Among them is our Conservation Champion for April 2020, Omar Monsegur-Rivera, a man who watches out for the diverse and numerous endangered flowering and non-flowering plants of Puerto Rico. Deeply respected and admired by his colleagues, Omar brings his passion for plants to work each day and effectively moves recovery actions forward. Through his actions, some of the rarest ferns in Puerto Rico are thriving in cultivation at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden. We are grateful for your dedication, Omar.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I grew up in a humble family that used to have a shade coffee plantation in west Puerto Rico. I was indirectly exposed to the concepts of native forests and forest ecology since I was a kid. I vividly remember the open forest understory covered by ferns and the native orchids such as Wydler’s dancing-lady orchid (Oncidium altissimum) growing on the trees. My university career changed in 1998 when I took the General Botany course, and at the same time, I was invited by a friend to join a trip to the Mona Island Natural Reserve (an island between Puerto Rico and Hispaniola). The trip was part of the Plant Taxonomy course – a subject of which I had no clue – and there I was exposed to the basic concepts of plant taxonomy and conservation. Following this, I was hooked. I continued taking advanced botany courses as an undergraduate and even collaborated on a project to conduct germination trials for an endangered grass endemic to southwest Puerto Rico.

What was your path to becoming a USFWS biologist?

In 2002, I started working as a technician on the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) for Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, a project under the Southern Research Station (USDA Forest Service). This opportunity exposed me to different ecosystems and a broader spectrum of forests (from early successional forest to pristine habitats) in Puerto Rico. I returned to the University of Puerto Rico to pursue an M Sc. degree, working on the “Vascular Flora of the Guánica Commonwealth Forest.” This project provided me the opportunity to continue working with endemics and federally listed plant species. I was lucky to work with other graduate students doing research on federally listed species or narrow endemics. During this time, I collaborated on a project to digitize historical collections from Puerto Rico deposited at the New York Botanical Garden. Later, I collaborated on a project to update the conservation status of Gonocalyx concolor and Varronia rupicola, a project sponsored by the USFWS. This was a step forward on my professional career. When I started as a Fish and Wildlife Biologist in 2009, I led the work on the listing rule and critical habitat designation for V. rupicola. This is a plant I had known since the time of my work at the Guánica Forest, when it was considered to be extirpated from mainland Puerto Rico, but we recorded it in several new localities.

With the USFWS, I have been able to extend my work on V. rupicola through collaborations, especially with researchers at Royal Botanic Garden, Kew. These collaborations have grown to include other species – finding information valuable to the recovery of species across Puerto Rico and beyond.

What are the challenges to conserving plants in Puerto Rico/the Caribbean?

The Caribbean is a biodiversity hotspot whose ecosystems are threatened by tourism, urban development, and the unsustainable use of natural resources for subsistence (particularly on the island of Hispaniola). The U.S. Caribbean currently harbors 52 plant species listed under the ESA, and this number will continue to increase. One priority for Puerto Rico is the need to identify and protect areas that still harbor remnants of pristine habitats and high plant diversity. The other challenge is to identify priority species and to develop sound projects that really address the conservation of our species. In parallel, we need to engage key partners and students.

With the impacts of Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017, we learned first-hand the reality of catastrophic hurricanes and the importance of having strong monitoring projects and prioritizing susceptible species. That motivated us to work with partners on the monitoring of key species (e.g., Gesneria pauciflora, V. rupicola and V. bellonis). Fortunately, we have documented that our species are able to cope with such disturbance when habitat remains in good condition. Again, the role of remnants of pristine native forest proved to be critical.

What has surprised you about working to conserve ferns in particular?

Ferns exemplify the problem of knowledge transfer, or lack thereof, in plant taxonomy and conservation. Following the retirement of Dr. George Proctor, the fern expert for Puerto Rico, no one carried on his work, resulting in a gap in knowledge. The taxonomy of this plant group is changing drastically with new approaches in phylogenetics, and the Caribbean is no exception. In addition, ferns are more vulnerable to climate change due to their reproductive biology and microhabitat requirements. They are therefore more susceptible to the effects of the historical deforestation of Puerto Rico for agriculture. The forest cover of the island has rebounded drastically in recent years, from roughly 6% in the 1930s to 50% currently. However, these are predominantly young successional forest dominated by exotics, which may not provide acceptable microhabitat conditions for the establishment of self-sustainable populations of rare and endangered ferns. Collaboration with Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden has allowed us to secure ex situ conservation of some of our endangered ferns and to engage new partners at the University of Florida to address taxonomic issues for other taxa.

What current projects or approaches in plant conservation excite you most?

I am collaborating with colleagues from Kew’s U.K. Overseas Territories Program and the National Park Trust of the Virgin Islands to extend ongoing conservation efforts across a group of islands known as the Puerto Rican Bank. Current efforts focus on population genetics, phylogenetic placement, and the reproductive biology of V. rupicola, V. bellonis and Zanthoxlyum thomasianum. One of the recent outcomes of this collaboration is the discovery of a new population of Solanum conocarpum at Tortola in the British Virgin Islands, a shrub once considered endemic to St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The species is already under ex situ conservation at the J.R. O’Neal Botanic Garden in Tortola, and the team is working to address the species’ population genetics across its range. Parallel to these projects, we are developing an initiative to work with our endemics and plants of conservation concern.

IN MEMORIAM

It is with a sad heart that we share that former Center for Plant Conservation Trustee, Erica Leisenring, passed away. Erica served as a CPC Board of Trustee from 2014 through 2018. She was a former St. Louis City public defender, who had also practiced family law. Besides her board service to CPC, she served on a variety of non-profit boards in St. Louis and volunteered as a tutor at an urban public school. Erica was a member of The Garden Club of St. Louis and loved to spend time in her small, city garden. She was a wonderful, thoughtful colleague and a great champion for plant conservation. Erica is survived by her husband, Robert Sears, and their two sons, Ned and Henry, their wives, and by her mother, Julia Leisenring, also a former CPC Trustee. We will all miss her.

We share sad news from our colleagues in Hawaii that Betsy Gagne passed away in March. Betsy’s breadth and depth of knowledge and work in the protection of Hawaii’s natural resources inspired many to devote their life’s work to conservation. Betsy graduated from the University of Hawaii and taught in Papua, New Guinea. Returning to Hawaii, she participated in the Hana Rain Forest Project where she reported having seen three small birds with black faces, colored like a chickadee. This was the first ever sighting of the po‘ouli. Betsy was the first biologist to see Miconia calvescens in Hana in 1991. Knowing the devastation that the plant inflicted on Tahiti, Betsy and her husband Steve Montgomery mounted a 15-year campaign to get the “green cancer” on Hawaii’s Noxious Weed list, prohibiting its importation. In the 1990s, Betsy served on Natural Area Reserves Commission, later becoming their Executive Secretary.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today