Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

August 2018 Newsletter

Volunteers are really the lifeblood of many non-profit organizations. These dedicated individuals serve in a multitude of capacities from administrative to mission-focused science to on-the-ground efforts to save species. What each of these individuals brings to the table, regardless of role, is a devotion that transcends compensation. Volunteers bring a sense of purpose to conservation that cannot be found elsewhere. These leaders, trained in so many fields and experienced in so many ways, provide not only willing hands but also essential guidance and mentoring for many of us who engage in conservation professionally. In this way, volunteers truly bind programs together in ways not possible otherwise.

This August’s issue of Save Plants highlights the role volunteers play in several critical conservation efforts around the country. Without volunteers, many of these programs could not even function, let alone achieve the level of success that they have. And while we do thank our volunteers early and often, it never hurts to do it again and again. So from me, a big thank you to all volunteers – past, present and future – that make what we do to Save Plants as successful and rewarding as it possibly can be.

The Hunt is On: Searching for Rare Plants in the Golden State

Amy Patten, the California Native Plant Society’s new Rare Plant Treasure Hunt (RPTH) coordinator didn’t venture far to lead her first hunt – Mount Hermon in the Santa Cruz Sandhills is just behind her home. But the spaces closest to us often face great threats, and this holds true for the sandhills, where 40% of the lands have been lost to mining and other development and what remains is threatened by invasive plant species. Despite the threats, the area still supports a unique community of plants and animals very different from the evergreen forests surrounding it. This uniqueness is due to the outcrops of Zayante soils, which have low water and nutrient availability. One of the plants endemic to the sandhills was the target of Amy’s RPTH, the Ben Lomond buckwheat (Eriogonum nudum var. decurrens).

Amy and her co-leader Rebekah Boettcher, a naturalist from the Mount Hermon Association, led seven amazing volunteer botanists in their July search. As the group hiked through the coastal ponderosa pine forest up to the summit of the mountain, they checked areas with bare, sandy soil for their quarry, the umbels of creamy flowers and leafy green basal leaves of the buckwheat. And find them they did: expecting to only find the species in the small, isolated area where they’d been previously observed, the group was excited to find several thousand plants in the area!

Upon reaching the core of the Ben Lomond buckwheat population, the volunteers helped describe habitat characteristics of the buckwheat and the surrounding plant communities, and evaluated threats and disturbances of these rare plants. The volunteer group fanned out in a transect to estimate the size of the population: the larger group of observers was able to find plants that a single surveyor could’ve missed.

As with all of the over 20 treasure hunt outings held this year, Amy’s resulted in a better understanding of a rare species population. Besides reporting a few thousand individual buckwheat plants and expanding the area of its known occurrence, the treasure hunters were able to do the same for Ben Lomond spineflower (Chorizanthe pungens var. hartwegiana), a federally endangered sandhills endemic. The previous occurrence records for these species hadn’t been evaluated in decades and were not accurately mapped.

The lack of knowledge about species is common throughout the state of California. Many rare plant occurrences haven’t been seen in decades, and many corners of the state are yet to be explored. In 2010, CNPS decided to build the RPTH program for their incredible network of volunteers to provide the CNPS Rare Plant Program and California Department of Fish and Wildlife with data that can guide conservation and management for the state’s 2,300 rare species. So, besides leading hunts, Amy coordinates RPTH efforts throughout the state, coordinating with CNPS’s 35 chapters and volunteers, as well as CNPS staff and other researchers, throughout the state.

Gathering a group of California native plant enthusiasts to search for Ben Lomond’s buckwheat endemic expanded not only the knowledge of the species to inform management, but also the local support and appreciation for the species. Besides reporting occurrence information to CDFW and CNPS, Amy can provide the landowners (Mount Hermon Association) with better management for these species. She also has a group of capable volunteers willing to return and tackle the mapping of silverleaf manzanita (Arctostaphylos silvicola) – the dominant shrub of the sandhills that also happens to be a rare county endemic. CNPS will also be back to collect Ben Lomond buckwheat seed, now that they know there are enough plants to make a seed collection without impacting population viability.

CNPS is a volunteer driven organization. Chapter volunteers coordinate meetings featuring educational talks, plan outreach events in their communities, put on native plant sales, and lead field trips. And they are essential to helping CNPS accomplish conservation goals. As the new rare plant treasure hunt coordinator, Amy is excited to engage more of CNPS’s fabulous volunteers and hunt for more of California’s rare plant treasures.

If you’re interested in collecting rare plant data and/or leading field trips with local chapters, visit the CNPS webpage to sign up for their mailing list and fill out a volunteer questionnaire!

25 Years of Survey and Discovery

New England Wild Flower Society

Contributed by: Laney Widener

Photos by: Laney Widener, Doug McGrady, Susan Elliott, Warren King, Kate Kruesi, and Matt Charpentier

Last month, Doug McGrady, a Plant Conservation Volunteer with the New England Wild Flower Society (NEWFS) for 15 years, created a buzz in the New England botanical world with an amazing discovery on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. He found a population of the federally listed chaff-seed (Schwalbea americana), a species in CPC’s National Collection historically found in New England, but which hasn’t been seen there in over 40 years!

Doug’s discovery demonstrates how just having volunteers out looking for rare species is a boon to conservation efforts, because we cannot protect species if we do not know they are there or how they are doing. Which is precisely why the NEWFS has been running their Plant Conservation Volunteer Program (PCV) for 25 years. As the oldest rare plant monitoring program in the United States, the program utilizes Citizen Scientists to help monitor, collect seed, and manage rare plant populations across New England. PCV is a subset of NEWFS’s New England Plant Conservation Program, a program that allows member organizations to coordinate research and conservation projects.

PCVs are the essential on the ground field botanists for both the New England Wild Flower Society and each of the six New England State’s Natural Heritage Programs (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont). Each state has only one State Botanist, and NEWFS only a handful of conservation staff, so the PCV program allows for so much more work to be completed year to year. The program has grown to a consortium of over 120 professional botanists and over 500 amateur botanists, an impressive force which now plays a critical role in rare plant conservation in the region.

A quick snapshot of what the program accomplishes on a yearly basis demonstrates its importance: between 300 and 400 rare species surveys are completed and around 120 seed collections are added to the seed bank. For perspective, New England has about 593 taxa considered of conservation concern, ranking from globally rare to locally rare, and historic to indeterminate (a designation meaning presumed rare but not confirmed). Historic and indeterminate rankings are often written off as lost but, as the chaff-seed story demonstrates, this is not always the case.

-

Plant Conservation Volunteer Deb Parella is collecting seed off of hairy wood-mint (Blephilia hirsuta) -

Vermont volunteer Katie Kruesi makes a seed collection of the threatened highlands rush (Juncus trifidus) earlier this month -

Volunteers helping to monitor Coast violet (Viola brittoniana) at a project site New England Wild Flower Society has been managing for 10 years in Massachusetts -

Alpine goldenrod (Solidago leiocarpa) on a ridge top line in New Hampshire. Photo by Matt Charpentier -

Volunteer Warren King and Aaron Marcus, Assistant Botanist for Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department, use their “forensic” botany skills to find a rare plant at a November Volunteer Wrap-Up meeting. Photo by Susan Elliott, VT PCV, 2017 -

Coast violet (Viola brittoniana) in Massachusetts. Photo by Laney Widener

Over his years of volunteering, Doug, the discoverer of the chaff-seed population has garnered a reputation as someone who finds new populations of plants every year. Recently he has expanded his volunteer role by taking a role on the Rhode Island Task Force professional advisory group. And he is just one of the 500 or so volunteers involved in the program. There is also Warren King, a plant enthusiast, who has been a PCV for 12 years and has been added to the Vermont Task Force professional advisory group. Warren has studied Eastern Jacob’s ladder (Polemonium vanbruntiae), another National Collection species, for many years, publishing his surveys and studies of this rare Vermont species in the Journal of the New England Botanical Club, Rhodora, earlier this year. Clearly the program tends to attract and retain passionate volunteers committed to conservation and the study of botany.

Key to retaining such dedicated volunteers, NEWFS works hard to give back to them. Every year field trips are planned for the PCVs to a site of botanical interest, often to an area where rare species are found. These field trips allow volunteers to lean about a specific species or ecosystem from a professional botanist. At their spring training, or refresher sessions, guest speakers come and give an educational or entertaining talk and the state heritage program staff are invited to come and talk directly with the volunteers. Each season ends with a “Wrap Up,” a volunteer appreciation event with a potluck and review of the field season. Wrap Ups provide space for volunteers to share stories and photos of their field season, reflect on what could be improved, and connect with all the other volunteers. NEWFS also recognizes the volunteer in each state who submits the most seed collections with a “Bountany” prize (a portmanteau of bounty and botany). They plan to further incentivize submission of survey forms this year by offering unique patches and stickers.

Like most plant life on the planet, rare plant species in New England face the four horsemen of the ecological apocalypse: habitat destruction, over-exploitation, climate change, and invasive species. The contributions of NEWFS’s volunteers over the past 25 years and future contributions will help provide information to improve management and conservation decisions for these rare plant species as they face these challenges. Running a regional rare plant monitoring program is a huge endeavor, and without the help of volunteers, the New England program could not exist at the scale it does today.

For more information about the PCV program, check out the NEWFS website.

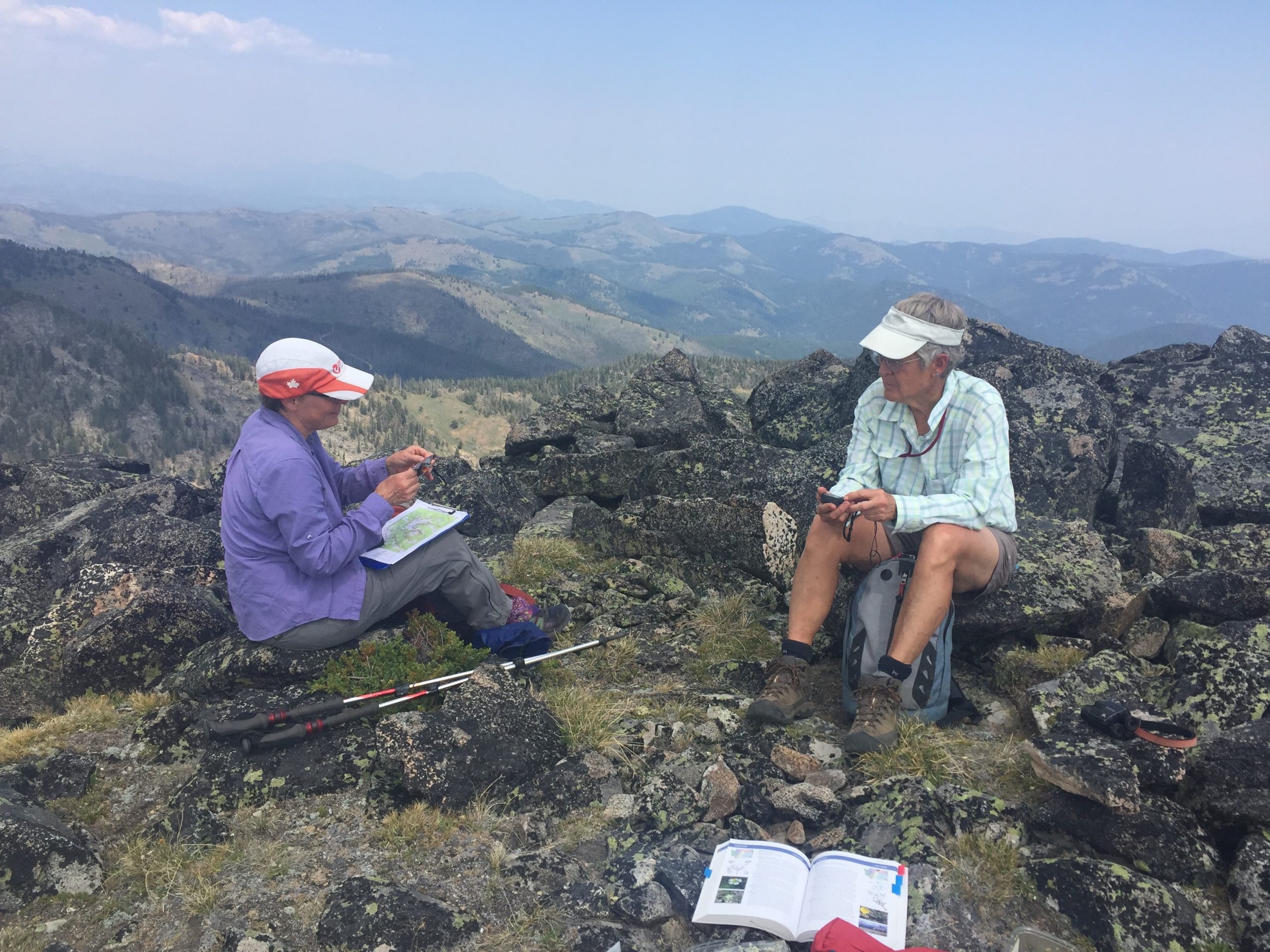

Wandering Washington with Rare Care Volunteers

This July, the Tiffany Springs Campground in the Okanogan National Forest was briefly invaded by volunteer botanists. The 18 volunteers were gathered for the annual Monitoring Weekend event held by the University of Washington Botanic Gardens’ Rare Plant Care and Conservation (Rare Care) program. Each year a location with many historical records of rare plants that have not recently been visited is chosen for the volunteer crews to put their skills to work. Over the three days of this year’s event, the volunteers completed 35 reports for historical locations on 9 different species – making it the most productive Monitoring Weekend on record!

The event demonstrates the hard work and dedication of the volunteer citizen scientists which help power Rare Care. The volunteers are passionate about the natural world and plant conservation, and eager to help. The program recruits for three types of volunteer work: rare plant monitoring, seed collecting, and seed cleaning. But the bulk of the volunteer efforts go towards the monitoring efforts, with over 100 volunteers willing to navigate across remote areas of public – and sometimes private – lands, climb up cliffs, wade through head-high nettles, and brave the elements in search of rare plants. Though the volunteers are provided with training, including orienteering, the volunteers work on their own. Rare Care staff provide them any historical data and maps, but it is their responsibility to research the plant ahead of their trip, be able to correctly identify it from possible look-a-likes in the area, research how to best reach their site, and then of course take all the monitoring data.

The data volunteers collect are then shared with the Washington Natural Heritage Program to update inventories on rare plant populations across the state, and will be used for land management decisions and conservation planning. Rare plant monitors perform one of the critical first steps of conservation by visiting known populations of rare plants, collecting data on the population, and reporting any threats observed during the visit. In many cases these sites haven’t been visited in over a decade or more.

For some species of interest, monitoring may be more frequent than others. A couple of ongoing Rare Care monitoring projects with various partners are centered around species that area also in the CPC National Collection: Wenatchee Mountain checkermallow (Sidalcea oregana var. calva) and Whited’s milk-vetch (Astragalus sinuatus). Both these species are endemic to the Wenatchee region and face various threats, from development to changes in fire regimes.

Wenatchee Mountain checkermallow is a perennial herb with beautiful pink inflorescences. Federally listed as endangered, the species occurs in only five locations. Partnering with the Department of Natural Resources, each year Rare Care volunteers count individual plants and map populations in order to study population trends over time.

Whited’s milk-vetch known from only eight populations scattered along only a couple of drainages. Rare Care volunteers have been working with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to monitor the largest of these populations through annual counts of individual plants in permanent transects and tracking the different life stages to better understand recruitment and mortality. Back at the University of Washington Botanic Gardens, seeds have been propagated for outplantings with the BLM.

Since it began in 2001, Rare Care volunteers have monitored over 330 species of plants, mosses, and lichens listed as endangered, threatened, or sensitive by the natural heritage program. And monitoring really does matter: the data collected by volunteers on the Washington state endemic grey cryptantha (Cryptantha leucophaea) led to a change in status from sensitive to threatened and brought much needed attention to the conservation needs of the species. Volunteers revisited 33 of 46 sites, documenting a 75% population decrease at over 10 of the sites. Rare Care worked with the BLM to monitor known locations, survey for new ones, and, fortunately given the decline, to collect seed from various locations.

Rare Care staff make sure to recognize their volunteers in a number of ways throughout the year. At an annual appreciation event held toward the end of each summer, all UW Botanic Garden volunteers enjoy the gardens with food and drink, receiving awards, and sharing stories. Within Rare Care, volunteers are invited to annual forums in various locations around the state where experts are brought in to speak about various topics ranging from pollinator identification to navigation techniques. At these forums, a special volunteer is honored for their accomplishments with a gift and later featured in the bi-annual newsletter. But, as a passionate group, the volunteers keep at it because of the importance to conservation and the amazing work they do.

To learn more about Rare Care, and the volunteer opportunities they offer, check out their University of Washington Botanic Gardens’ site.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today