Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

March 2020 Newsletter

Today we have the pleasure of sharing good news about the rediscovery of plants once thought to be extinct and the great work our Participating Institutions are doing to recover the species in the wild. Learn how new technology is helping us explore hard to access locations, the heroic efforts required in the laboratory, and great restoration results.

Joyce Maschinski

CPC President & CEOHanging on the Edge and Flying High

While dangling from ropes on a cliffside in Kaua’i, Research Biologist Ken Wood made an exciting discovery – a previously undescribed species of hau kuahiwi, or mountain hibiscus (Hibiscadelphus), a rare genus found only in Hawai’i. The 1991 discovery took place during a series of intensive surveys of Kaua’i’s Kalalau Valley by the National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG). Only four plants were found in this inaccessible spot. As much information as possible was collected, and the species was eventually named H. woodii after its discoverer.

Sadly, only a few years later a rockslide would wipe out three of the individuals. The last one was found dead in 2011. Though the species was declared extinct, the NTBG knew more pockets of the plants might exist on the steep cliffs of Kauai’i’s valleys. But the dangers and time commitment required to explore the hazardous area (even for the intrepid Mr. Wood) were daunting – until Ben Nyberg and his drones came into the story.

Ben joined NTBG as a GIS specialist, but also brought experience in flying drones from his previous consulting work. Seeing great promise for the use of drones in plant conservation, Ben navigated the ever-changing landscape of flight regulations and permits – an 18-month process – and launched a drone program on Kaua’i in early 2017. Initially the drones were used for aerial imagery and data capture for elevation models, and to assist with surveys for the Limahuli Garden and Preserve (an NTBG property). The power of drones in rare plant surveying quickly became apparent. The drones located several critically endangered plants early on, including laukahi (Plantago princeps var. anomala) and Euphorbia eleanoriae. To leverage this early achievement, he sought to upgrade the drones and expand the program.

The NTBG team successfully applied to the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund for a grant to aid in the rediscovery of H. woodii. With these funds, they were able to purchase a new, more portable drone with a 20-megapixel camera. The team identified potential habitats and selected accessible drone launch sites. Now experienced with piloting rare plant surveys and not rely solely on automated grid patterns for his flights, Ben focused on quality habitat on the cliffs as he searched for the rare tree. But the weather and limited battery life were still challenges that impacted survey time.

The surveys began, and the team anxiously awaited results. An initial scan for H. woodii in the vicinity of the original population came up dry. For a long stretch, further surveys of this area and the next few valleys over were delayed by rain – but the results were worth the wait. In January 2019, a drone flight caught the first glimpse of the species in nearly a decade.

It wasn’t instant cheers and celebrations, however. Ben and the botanists with him didn’t notice the rare specimen on the live view of the drone controls. It wasn’t until Ben was back in his office, scouring photos from the previous day’s work, that he noticed a promising tree-like plant with round leaves in the right hand corner of one image. Ben is not a botanist – though he has enjoyed learning to identify many plants during his time at NTBG – so he ran it by his colleagues to be sure. Who would be better for this than the plant’s namesake himself? Ken Wood worked with Ben to compare the drone photo to old photos and confirmed the find. This prompted a return visit to further examine the area. In the end, three individuals were confirmed, reviving hope for the species.

-

Ben Nyberg prepares the compact commercially available drone NTBG uses. Portability is important, as the flight area may still require a long hike, or even helicopter ride, to be accessed. Photo credit: Mark Query, courtesy of National Tropical Botanical Garden. -

NTBG botanist Ken Wood is no stranger to botanizing on steep cliffs. The drone can do searches efficiently and safely, and can help direct the field time of botanists like Ken. Photo credit: Ben Nyberg, courtesy of National Tropical Botanical Garden. -

Hibiscadelphus woodii was discovered in the 1990s, but the few individuals known were soon wiped out. Their rediscovery last year keeps hope alive that there may be even more plants, and more conservationists can do for the species. Photo credit: Ken Wood, courtesy of National Tropical Botanical Garden.

As with any rare species, location and abundance information is a huge step. But with H. woodii still out of reach for humans, the next steps for its conservation may also lie with drones. NTBG is partnering with engineers at University of Sherbrook and University of British Columbia, Vancouver, to explore the possibilities of adding cutting mechanisms and arms to the drones under a grant from National Geographic. Collecting genetic material, pollen, or even seeds of this rare species – or conversely painting flowers with pollen – could help move forward important conservation work. Ben is also looking into adding different sensors to the drone to collect more data than the typical photograph. Multi- and hyper-spectral sensors that record different wavelengths of light could help classify vegetation and identify plants, soils, and more.

Ben is also talking to the folks at Adobe, the developers of the Lightroom photo software, and ESRI, the mapping software company. Adapting these two pieces of software to better communicate the data from the photos would be helpful for NTBG and many other users. Also on the software side, artificial intelligence or machine-learning technologies may eventually be developed to shorten the times required for both field and office work by helping to identify good habitat and recognize target species.

For now, there are more rare plants to hunt! Guided by the Plant Extinction Prevention Program in Hawai’i and NTBG staff, Ben has a target list of cliff dwellers for which drones can play a useful survey role. He is also training other program teams to do botanical surveys with drones, increasing the efficiency of their field operations. The possibility that some of the plants discovered might be able to be brought into ex situ (off-site) collections for conservation work, like some of the other populations discovered via drone, is an exciting one. Meanwhile, the drones are playing a vital role in helping us to understand the distribution and abundance of these rare plants.

Clovers on the Rebound

Not long ago, running buffalo clover (Trifolium stoloniferum) was thought by many to be extinct. Yet, this past fall, it joined a select few species considered recovered enough for delisting from the Endangered Species Act. This noteworthy event is a result of the extensive work that has gone into recovery efforts, including propagation of hundreds of plants in the Plant Lab at the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden’s Center for Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife (CREW).

Running buffalo clover has a wide range, stretching from the Midwest to the Appalachians. The species relies on habitat with clear, obvious disturbances, such as the extensive buffalo trails that crossed the region before buffalo populations suffered a precipitous decline. This unusual life history trait may be the reason that running buffalo clover was undetected between the 1940s, when it was initially thought to be extinct, and its rediscovery in 1983 by a botanist with the Nature Conservancy. This preference for disturbed regions also guides land management efforts under way to conserve the species.

Kentucky is one of the many states to rediscover populations of running buffalo clover. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has led projects there to establish new populations on private lands, reestablish populations at sites where they have disappeared, and support a research population at Eastern Kentucky University. When a large number of plants were needed to make these efforts succeed, CREW seemed the obvious choice. Brent Harrel, one of the USFWS project leads, had been impressed by a tour of the CREW facility. Other collaborators from Kentucky Nature Preserves had previously worked with CREW’s Valerie Pence, Ph.D., and her team. According to Harrel, the CREW team were the potential collaborators they approached who best “understood what our objectives were and could produce the numbers we needed.”

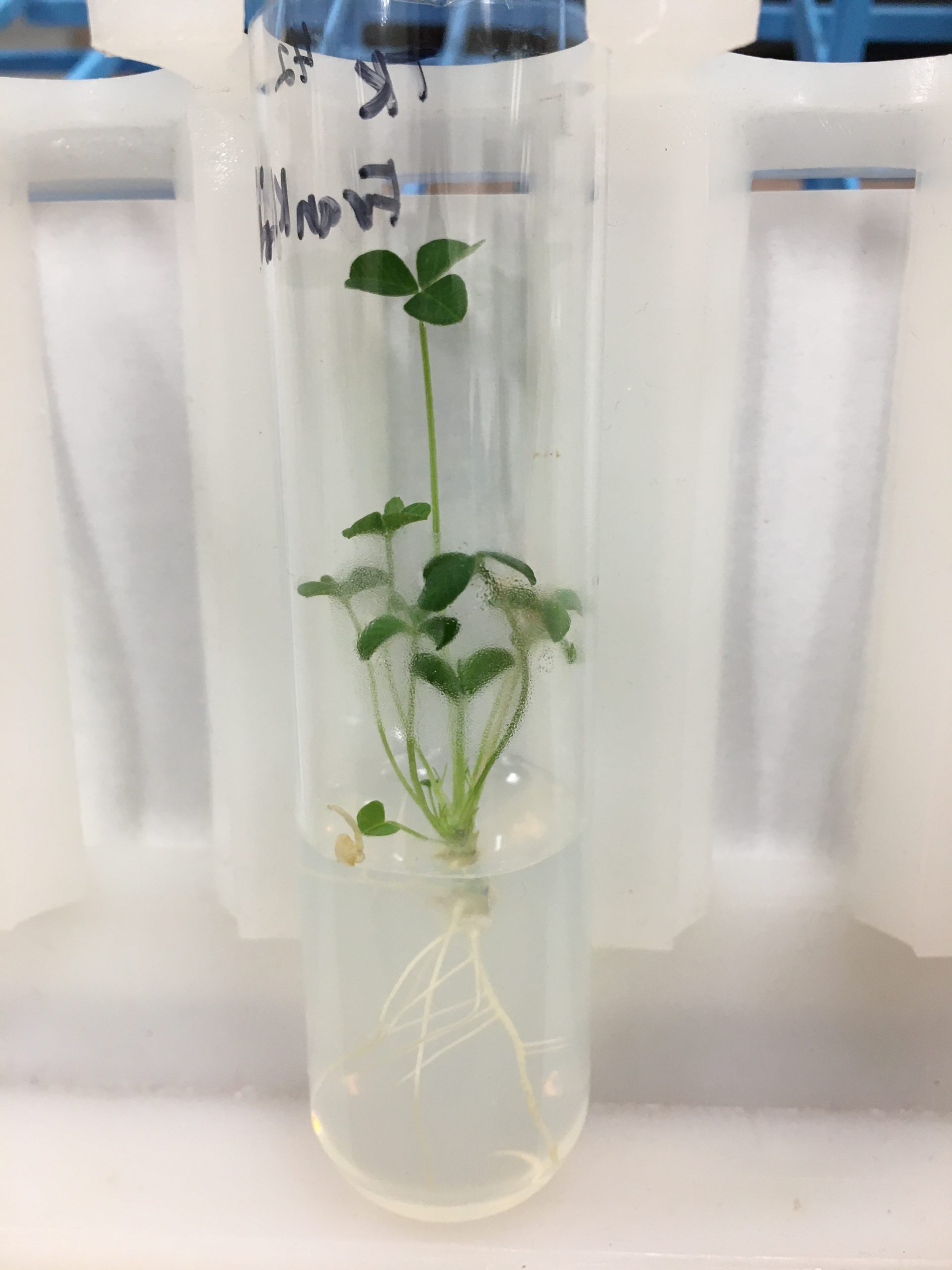

Valerie had earlier been intrigued by a 1988 study out of West Virginia University on the tissue culture propagation of running buffalo clover. The study demonstrated that the species could be propagated in vitro (in a sterile test tube environment), giving the CREW team a promising start. Once the decision for in vitro germination was made, propagation turned out to be rather straightforward, and less challenging than in many species. Scarifying (nicking) the small, hard seed with a scalpel proved to be difficult, but it gave the best germination results and became part of the final protocol.

The scalpel work is done on a sterile surface with a dissecting scope. The seeds are then placed on a simple growing medium of salts and sugar that is dilute (half the typical concentration) and has no plant growth regulators. The growing plants are protected and nourished in the in vitro system until they develop into robust seedlings with significant root development. At that stage the plants graduate to soil – but they cannot instantly transition from cozy in vitro tubes to the harsh outdoors. Once in soil, the plants are first kept in a humid environment and only gradually weaned into drier conditions, first in pots in the greenhouses and eventually outside.

Pampering the plants with a nice, controlled, in vitro environment proved very effective. Though the seeds can be scarified and germinated in soil, the combined in vitro-soil method resulted in higher efficiency with loss of many fewer plants. Plants germinated directly in soil were at the mercy of the greenhouse – too much afternoon sun or not enough water reaching the edges of a tray, caused damage or loss. Staff at the CREW tissue culture facility found it more predictable, and ultimately easier, to start the seeds in tubes.

Valerie and her team do not often get to see their plants reach their ultimate destinations. With running buffalo clover, however, they were able to participate in an outplanting (transplanting from a facility to an natural area) at a site owned by Eastern Kentucky University. The team found it incredibly satisfying to take part in the return of the species to its home.

New homes for Brent Harrel’s plants have also been established throughout Kentucky. The plants were cared for regularly in their first year and then monitored annually. A decade has passed since the work was initiated and some of the populations are doing very well. Though, as with many large reintroduction efforts, the results overall have been mixed, despite careful site selection. There is still more to be learned about the species. However, the work done to date shows that it is possible to establish new populations and expand existing ones, given appropriate conditions and management.

The delisting of running buffalo clover from the Endangered Species Act is currently pending. The USFWS will continue to keep a watchful eye on this species and encourage conservation partners to do the same. Meanwhile, Valerie and her team are expanding their propagation protocol for running buffalo clover to some of its relatives. The method seems broadly applicable. CREW has already applied the unmodified protocol to buffalo clover (T. reflexum), an at-risk species in the Eastern U.S., and – excitingly – to T. kentuckiense, a newly described clover that seems to be endemic to two counties in Kentucky. The future for these rare species is looking hopeful!

All photos (except where otherwise indicated) by Valerie Pence, courtesy of Cincinnati Botanical Gardens.

Recovering Bradshaw’s Desert Parsley

Bradshaw’s desert parsley (Lomatium bradshawii) is a lovely member of the carrot family that may soon find itself coming off the endangered species list (or possibly downlisted to threatened). During much of the 1900s, this species was apparently thought to be extinct, until a University of Oregon graduate student rediscovered it. Or perhaps it was only considered rare and hard to find, but not really extinct. It is actually quite difficult to know whether a plant population is extirpated (no individuals remaining in a certain geographical location) or a species is extinct. But what is clear today is that Bradshaw’s desert parsley has a larger number of populations and more robust populations than it did when it was first listed in the 1980s – and the Institute for Applied Ecology (IAE) has played a large part in that success.

Found only in Oregon and Washington, Bradshaw’s desert parsley has lost habitat to farmland and other development. The remaining wild habitat is being impacted by changes in land management – specifically, the decline of fire in the ecosystem. However, when Tom Kaye, executive director at IAE, began his graduate work on the species, there was only the slightest indication that fire might be important. His work documented the effects of fire as a management strategy at a handful of sites, with the data showing an increase in population size. The research suggests that populations can tolerate fire every year, and they may need fire at least every three years for population growth. A lack of fire at a site eventually leads to a population’s decline.

Grazing can potentially play a similar role in the management of the the parsley populations. Grazing, like fire, removes the thatch of plant material that can build up in the wet grassland systems the plant calls home. Thatch affects various living and non-living aspects of the habitat, including negative impacts by voles. These stout rodents seem to have a preference for the rare plant, and they have been seen piling cut pieces of the Bradshaw’s desert parsley next to their burrows. Reduction of thatch causes the voles to lose cover from predators. Fire or grazing may therefore make the Bradshaw’s desert parsley habitat less attractive and push voles to relocate to other sites, where their voracious appetites do less harm.

-

Early research into restoration practices determined that seeding into bare ground was a cost effective solution for this perennial species. -

Rare plants are important components of ecosystems – here Bradshaw’s lomatium supports a swallowtail caterpillar. The plant blooms early and is actually an important source of nectar for pollinators early in the season when little else is in bloom. -

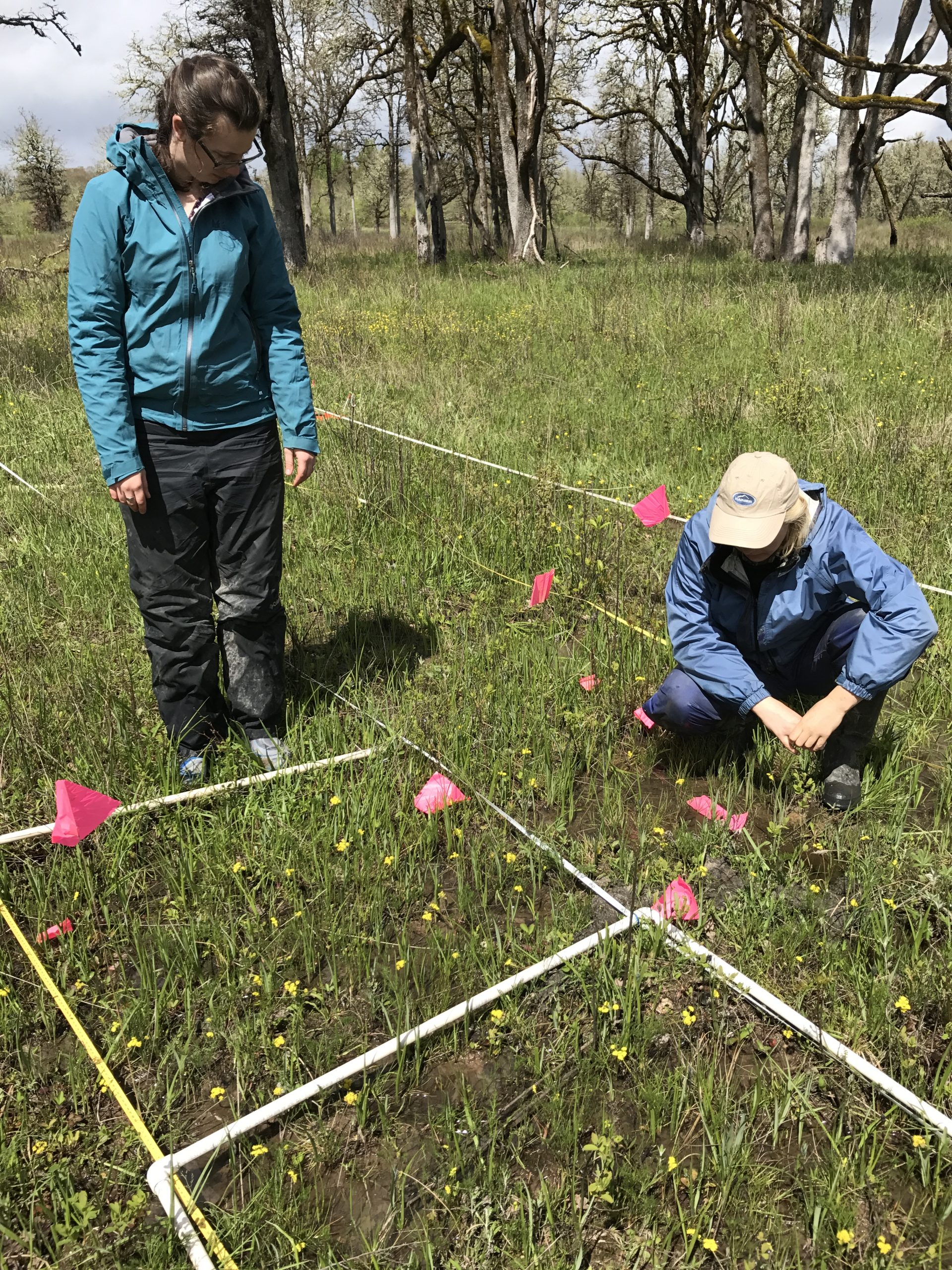

As part of range-wide survey, IAE staff monitored populations of Bradshaw’s desert parsley across Washington and Oregon.

At IAE, Tom focused on applied research for new population establishment. Using seed collected from the remaining wild populations, the IAE team produced small plants (“plugs”) and vast amount of seeds that they used to restore different locations. Plugs are more expensive than seed to grow out, install, and care for, but for many species they have higher survival rates. With parsley, however, the team discovered that the seed and plugs worked equally well. Applying the large seeds to bare soil (with thatch removed by burning or grazing) resulted in an impressive 30-70% rate of germination and plant development.

This technique was used by IAE at the William L. Finley National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) and other locations and was also put into use by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Many land managers have been great partners in the efforts to increase Bradshaw’s desert parsley across its native states. The Bureau of Land Management, Army Corps of Engineers, Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, local governments, and private land trusts have all supported restoration at some level. However, not all the reintroduction projects were being tracked long-term. Although it was clear that the situation was improving in many places, the big picture for the species was still blurry.

To fill this important information gap, IAE conducted a range-wide survey of Bradshaw’s desert parsley a few years ago. The survey provided updates on reintroductions that were no longer being monitored. One of the places revisited was a site on William L. Finley NWR that had been seeded but not checked on in years. Tom and crew expected to find a few hundred individuals in the area of the seeding. As they walked up to a happy patch of yellow flowers, they knew there were many more. But it wasn’t until they were down on their hands and knees in the survey plots counting all the little seedlings that they realized the population was around 10,000!

Even more valuable than an update on specific populations, the survey provided a snapshot of the overall status of the species. The number of populations reported in the survey supported the delisting requirements. However, Tom warns that a population “can decline at the drop of a hat” with management changes, and he recommends continuing to monitor the species at this scale to obtain more than a one-time snapshot.

Regardless of the endangered species status, management of Bradshaw’s desert parsley will be a continuing challenge. Balancing the disturbance needs of the parsley with the habitat needs of other species to promote diversity can be tricky. Although fire seems to be the best way to provide disturbance, it isn’t always logistically feasible. Grazing may help on “working” lands, such as ranchlands and farms, but it can be difficult to manage safely and consistently. Though the species is doing well for now, a great deal remains to be learned to help ensure its safe future.

All photos courtesy of Institute for Applied Ecology.

Wes Knapp, M.S.

Wes Knapp is leading an important effort to assess plant extinction in North America north of Mexico. Taking up this cause of understanding extinction has opened his eyes to the extent of our knowledge, and sometimes our lack of knowledge, about rare plants. Working with Natural Heritage Programs and in his spare time, he is helping coordinate field surveys and data sharing efforts to understand extinction so that we can better understand how to prevent it. His infectious enthusiasm for plants is key to leading this effort.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I was a late bloomer (pun intended), as I didn’t discover my love of plants until I was a sophomore at Catawba College in 1999. It was during Dr. Mike Baranski’s Field Botany class, where my eyes were opened to the abundance of life that surrounded me. I was taken back that you could use a simple text (this was an intro level class, so we used Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide) and rather quickly get to a species. I was hooked. I’m not sure if it was that class or Plant Taxonomy, the next year, where we took a field trip to the Green Swamp, which is now one of my favorite places on earth. This Nature Conservancy preserve is a gorgeous Longleaf Pine Savanna home to Venus flytraps, orchids, and numerous other carnivorous plants. I was overwhelmed by the diversity – it was a truly special moment.

What was your path to becoming a botanist with the Natural Heritage Programs?

My career has been a series of fortunate events. I conducted a flora of Dunn Mountain, Rowan County, NC, for my undergraduate project. It exposed me to a good number of plants, but I was truly unprepared for a position with a Heritage Program. Natural Heritage Programs usually maintain a state’s rare plant list, and that means you need to really know it all. Right out of undergrad I got a position with the Maryland Natural Heritage Program (MDNHP) to conduct a two-county inventory of “Ecologically Significant Areas.” It was a short 6-month position (or so), with no guarantee for future work. I took that job with no expectation of future employment, but used the position as on-the-job training and decided to learn as much as I possibly could. Chris Frye, MDNHP State Botanist, was my supervisor, while local experts Ron Wilson and Joan Maloof were working with me on the Significant Natural Area surveys. They truly mentored me. I will forever be indebted to them for taking the time to help me understand keys and plant structure. They really helped kindle my love for the underappreciated grasses, sedges, and rushes.

It was the next year, 2002, when I met Rob Naczi (previously Delaware State University and now New York Botanical Gardens) and began my graduate work on Juncus. I didn’t know it at the time but deciding to work with Rob to get my master’s degree was a transformative moment in my life. Natural Heritage Botanists are a combination of field and academic experts. Working with Rob helped me gain the necessary academic tools (statistics, scientific writing, etc.) that are critical for success. I stayed with MDNHP for 15 years until I accepted a position with the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program as Mountains Ecologist/Botanist.

Please explain the importance of surveys to botanical conservation.

Field surveys are absolutely mission critical for botanical conservation. They provide us with the basic knowledge and data conservationists need, including: what species exist, which are rare, where these rare species are found, how many of a species are found at each location, how well they are doing, and what threats are present at that given location. Nothing in our world is static. Our information is only aging, and – as we all know – the world is changing rapidly. What was once a secure population of a rare species may not be anymore. Surveys help reveal threats and trends, and this informs how we should best spend our very limited conservation dollars. The data we collect in the field as part of Natural Heritage Program network, which is eventually deposited with NatureServe, helps provide the basis for all species conservation decisions across the country.

What about working with plants has surprised you?

Frankly, I’m surprised at how little we know. There is still so much we do not know about the natural world that surrounds us, and so many places have yet to be surveyed for botanical diversity. Undescribed species are more common than you think. I’ve been a party to describing four species so far during my career, and that number will increase significantly given I’ve moved to North Carolina, a biodiversity hotspot. Currently, I’m working on as many as a dozen new species. The challenge is that describing an undescribed species is a laborious and time-consuming task that, at least for me, is something I do on my own time – “off-the-clock.” You have to gather, compile, and analyze lots of data to defend the description of a new species, and that process takes years.

What has been the most challenging aspect of your work?

Work-life balance. Most of my research is after work hours, so finding funds and time to conduct this research is challenging. It is compounded further because I am a husband and father of two girls (10 and 12 years old), and I try to be the best father I can – which means putting research off until the girls are in bed. A trade I’m happy to make.

What current projects or approaches in plant conservation excite you most?

My most exciting project is the Extinct Plants of North America north of Mexico. I’ve been leading this effort as a passion project for the past 7 years. It is rather intimidating leading a group of 15 amazingly knowledgeable botanists from across the United States. You’d think we’d know how many species have gone extinct and where they occurred, but we don’t. Each extinct plant tells a story and can teach us a lesson to help prevent future extinction events. There are so many facets of this work and so much future work to still conduct. Future work includes an attempt to identify single-site endemic plant species, as they are the species to most likely go extinct, and an attempt to resurrect extinct plant species using seeds on herbarium specimens.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Beauty and the Beast: California wildflowers and climate change | A new book by CNPS Press and Winter-Badger Press

Climate change and other human impacts on the environment are threatening wildflowers and the life that depends on them. In this special and timely work, conservation photographers Nita Winter and Rob Badger give us a spectacular view of California’s extraordinary wildflowers as both a cause for celebration and protection.

Read more

Order the book

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today