Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

We join colleagues around the world in celebration of the 15th annual Endangered Species Day, a day set aside to learn about endangered species and how to protect them. This month’s Save Plants pays tribute to life forms that are critical living partners of endangered plants that are often unseen, but directly or indirectly support healthy plants and a healthy planet. From diverse lichens that are soil creators and sensitive indicators of environmental change to soil crusts that allow plants to survive harsh droughts, we take a moment to appreciate the small entities that play a large role in our world. Like the rare native plants in the CPC National Collection, these small life forms benefit from heroes, who dedicate time to study their complex ecology or document and publish guides showcasing their diversity.

As you enjoy this venture into the seldom seen living (biotic) partners, we extend our gratitude to all of you for your partnership with us to Save Plants. We wish you and your families continued health and safety.

Joyce Maschinski

CPC President & CEOOur April newsletter offered a look at the work of CPC Participating Institutions beyond flowering plants. This month, we continue this exploration, focusing on the smaller, non-vascular plants, and even non-plants. Many gardens have recognized the importance of researching, collecting, and documenting fungi and lichens, due to their close relationships with plants. Sometimes these groups are collectively referred to as cryptogams. Though not evolutionary related (or even in the same kingdom), cryptogams are similar in that they reproduce “cryptically” – via spores rather than through showy flowers and seeds. The organisms themselves are often small, cryptic, and often overlooked .

Non-vascular plants lack the xylem and phloem that transport water and nutrients and provide structure in vascular plants. They include the bryophytes (mosses, hornworts, and liverworts) and green algae. Besides the lack of vascular tissue, bryophytes differ in other ways from the plants we tend to know. Their main structures are actually haploid gametophytes, like pollen in higher plants, having half the chromosomes of ‘adult’ plants.

Fungi are their own kingdom, but they often have very specialized relationships with plants. Famously, mycorrhizal fungi are associated with plant roots, helping the plant obtain water and nutrients and receiving carbon sugars in return. Even the more independent fungi play important roles in the ecosystem as decomposers, turning woody and fibrous materials into simpler forms that are available to plants. And, like plants, many fungi produce impressive fruiting bodies that catch our eyes.

Lichens are partnerships between algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of various fungi species in a mutualistic relationship. Lichens grow on and in a wide range of substrates and habitats, including some of the most extreme conditions on earth. Yet they are sensitive to physical conditions, especially air pollution, as they are unable to avoid the accumulation of pollutants. In fact, lichens may provide a useful service as biomonitors for human impact on the air.

CPC partners are working to increase our knowledge of these species – plants and non-plants – for their importance to all plants and the natural world. A shortage of expertise and opportunity makes this work difficult, but the relative few who study the diversity of mosses, lichens, and fungi, are passionate in what they do. CPC welcomes and supports their valuable contributions.

Disappearing Lichens and a Southern Appalachian Stronghold

Imagine if most native plants had vanished or become rare a century ago. As an Easterner, I try to envision the explosion of spring wildflowers in Appalachia reduced to only the few and hardiest. You might think of the impact in Southern California deserts, high country of the Rockies, Midwest prairies, or swamps along the Southeast coast. It is not an easy task. Native plants are central to how humans perceive the natural world and appreciate its value and beauty. Because native plants are so important to us, such losses are difficult to conceptualize.

Thankfully, although many native plants are imperiled, their absence is still a thought experiment. This is not the case for lichens.

Lichens are fungi that form beautiful, complex symbioses with algae and bacteria. They hold together soils, regulate the climate, allow seeds to germinate, and provide both food and shelter for all kinds of animals. These hubs of activity that bind nature together are incredibly important to nearly everything that lives on land. And many have vanished.

Understanding why they have vanished is simple: lichens are sensitive to change. Attached to the substrates they grow on, lichens cannot rapidly move to avoid fires, floods, or changing climates. They passively soak up moisture from the environment and can’t keep pollutants from entering their bodies. They are made up of specialized, highly adapted partners and can’t live without the right conditions for all the partners. Finally, they do not disperse very far, with each generation only a short distance away from its parents. Ironically, these very factors that allowed lichens to diversify and thrive – as long as they had a bit of fog and a substrate to grow on – now leave them poorly adapted to the challenges of the modern world.

The disappearance of the lichens has been chronicled by naturalists for nearly two centuries. An early naturalist noted their loss from Dickensian England as cities grew and air quality decreased. A lichenologist documented their loss in Paris during the Industrial Revolution. In the United States, urbanization, deforestation, and the Industrial Revolution have spurred the loss of Southern California lichens. There was once a lichen desert covering tens of thousands of square miles in Pennsylvania and the Ohio Valley. Nearly all of New York City’s hundreds of species were pushed out of the boroughs.

Happily, air quality across the U.S. has improved since the Clean Air Act was passed in 1972. Lichens have begun to return to areas where they once were numerous. But most have yet to recover.

Many species are rare and are commonly found only in unique areas that have been protected and remain relatively undisturbed. Although areas of conservation concern have been established for native plants, lichens do not follow the same patterns. Finding these areas for lichens and recognizing their value for conservation are now critical. I have the privilege of working toward this goal as a member of a small but dedicated group of lichenologists from across the United States and Canada.

One of the priority areas for lichen conservation is Appalachia, especially the southern mountains in Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. For more than a decade, I have worked as a lichenologist for the New York Botanical Garden, together with colleagues and students, to build the case that this area is a global hotspot for lichen diversity and one that is critically imperiled.

The region is truly special. We have found dozens of species new to science. Some of these are restricted to mature individuals of specific tree species that grow in the largest remaining tracts of old-growth forest east of the Mississippi River. Studies with Dr. Erin Tripp and Dr. Christy McCain at University of Colorado, Boulder, have confirmed that patterns of lichen diversity in the region are driven by habitat quality and disturbance. My colleagues and I have found species still relatively common in the southern Appalachians that have declined greatly in other parts of North America. A team of lichen specialists, led by Dr. Jessica Allen at Atlanta Botanical Garden, have begun to rank and assess these species as part of a broader effort to increase representation of lichens among biodiversity recognized to be in need of conservation and protection. Appalachian Matchsticks (Pilophorus fibula), Hot Dots (Arthonia kermesina), Virginia Square Britches (Hypotrachyna virginica), and the Rock Gnome (Cetradonia linearis), are just a few of the lichens that have been assessed as endangered and added to the IUCN Red List as a result of these efforts.

Great Smoky Mountains National Park has long been recognized as central to protecting the vast diversity of life in the southern Appalachians. My colleagues and I have documented nearly a thousand species from the park – more than from any other national park in the United States. But it is difficult for the average person to access the hidden world of diversity where these lichens still abound and thrive. That is why, in addition to all of the efforts to document and conserve lichens that make the southern Appalachians so special, we have published a Field Guide to the Lichens of Great Smoky Mountains National Park – the only modern field guide for a North American region that covers more than just the most common and conspicuous species.

The lichens in many areas of the United States have suffered steep declines. That is precisely why those that remain must be recognized and conserved. Lichenologists have shown that setting conservation priorities for these amazing organisms can be achieved and we hope that many more success stories will add to what we have accomplished in the southern Appalachians.

Entangled by Rocky Mountain Fungi

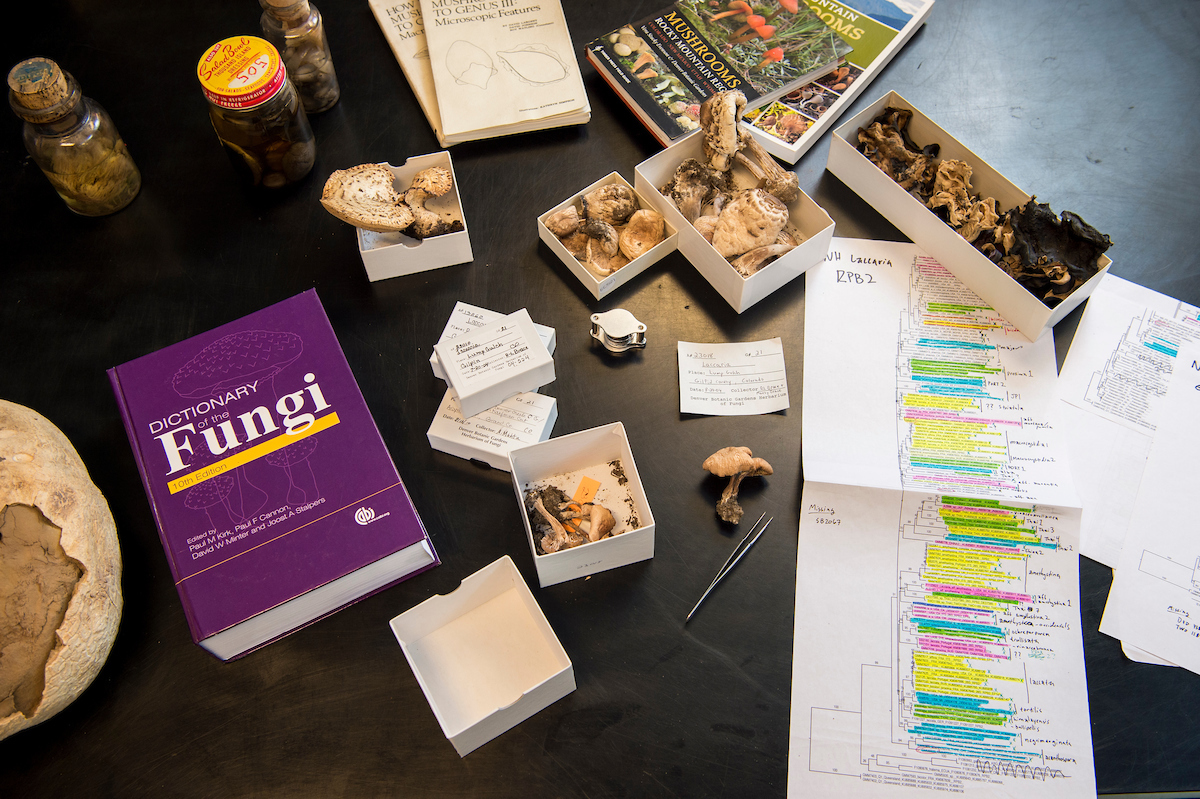

Mycological and botanical research at Denver Botanic Gardens mirror each other and both will be moving into a new facility soon. The new Freyer-Newman Center at the Gardens will highlight these natural history collections as part of the institution’s effort to promote science, art, and education. The link between plants and fungi is widely recognized now at the Gardens and beyond. “Now we know that plants are absolutely dependent” on fungi, says Vera Evenson, Curator Emeritus the Sam Mitchel Herbarium of Fungi at Denver Botanic Gardens. Fungi form intimate contact with their food source and they often have special relationships with plants. Some fungi are mutualistic symbionts in a two-way beneficial relationship with a plant, while others are parasites. Other fungi are saprobes, recyclers of the natural world that decompose the tough material of a forest and make it available once again for plant uptake. In short, without fungi, there would be no plants as we know them. And we all know that without plants, there would be no animals – including us!

Yet public perception of fungi is limited. They think about edible mushrooms (or possibly fungal infections they’d rather avoid), if they think of fungi at all. But mushrooms are just the fruiting bodies of much larger fungal organisms. The vegetative part of a fungus, called the mycelium, consists of a network of fine filaments that crisscross soil or a host organism. The combination of this fascinating (and important) network with intriguing fruiting bodies has enticed many a naturalist into learning more about fungi.

Vera found herself caught up by fungi back in the 1980s. On a camping trip, her children returned from a nature exploration with armfuls of colorful mushrooms they had collected. Feeding off their curiosity, Vera promised to tap into her experience with fungi from her Master’s degree in microbiology. A lack of resources left her initial efforts to identify these large fungi fruitless, however. She turned to Denver Botanic Gardens, where she encountered one of the largest macrofungi collections of the Rocky Mountains. There she met Dr. Sam Mitchel, a medical doctor with a fascination for fungi that began decades earlier while hiking through Colorado. His collections formed the foundation of a future fungi herbarium at the Gardens: the Sam Mitchel Herbarium of Fungi.

The meeting with Dr. Mitchel had a profound effect on Vera, leading her to years of volunteering, joining the Garden’s staff, and eventually becoming curator of the fungi herbarium. Vera has worked to not only collect and care for the collection, but also to share her knowledge of and passion for fungi. She and her colleagues at the Gardens and the Colorado Mycological Society (CMS) have conducted many outreach events to entice more people to learn about the fascinating world of fungi.

Vera finds a ready audience. “The public is interested!” she exclaims, “and not just in eating them.” Recently there has been an uptick of interest in the many uses of fungi – as medicines, decomposers, and even a source material for roof shingles and more. The Annual Mushroom Fair, hosted by the CMS in collaboration with the Gardens, draws more than 2,000 people each year to be amazed by the specimens and educational displays. For Vera, it’s fun to see and hear people learn there is more to mushrooms than the foods they are familiar with, keeping an ear out for the surprised “Is that a mushroom?!”

The collection at the Sam Mitchel Herbarium of Fungi contains more than mushrooms. The Gardens focuses on documenting the diversity of all macrofungi – species that generate large and visible spore-producing structures, such as mushrooms, puffballs, coral fungi, and cup fungi – in Colorado and beyond. These collections, mostly from montane forests, vary from the famously edible morels, porcinis, and chanterelles to huge fairy rings of giant puffballs. Sharp-eyed collectors have spotted tiny and colorful rare cup fungi in bogs and fens, or huge, often bitter-flavored woody polypores (conchs) growing high on the side of trees. Now housing nearly 30,000 unique specimens from Colorado and the rest of the Rocky Mountains, the collection is an invaluable regional resource.

Many years ago, Vera found herself having to defend the collection’s place at the Gardens. The fit of fungi at the Gardens was not obvious to everyone; ideas to dismantle or donate the collection floated around. It helped to have a mycologist from the New York Botanical Garden assess the collection and argue the importance of it remaining intact as a regional resource. And a resource it certainly is. Collections continue to be made as herbarium staff and other researchers strive to document the diversity of macrofungi for the Colorado Mycoflora Project (part of a greater North American effort). By identifying the species of the southern Rockies and North America, researchers can create identification guides with which the public can learn more about these organisms. A comprehensive census of macrofungi allows researchers to begin to understand their importance biologically: how species are distributed, what ecological influences dictate species distributions, and how fungal interactions benefit biological communities. For all of this, the herbarium provides a valuable reference.

The collections are used to study taxonomy and generate DNA sequence data. DNA sequencing has been a game changer for mycological studies. Attempts to document the diversity of these, sometimes cryptic, species can be quite challenging. Traditionally, mycologists do a sort of triage by assigning species names and epithets taken from species that are not necessarily local. For example, if a local mushroom seems to match the description and image of a species in a European guide, mycologists will likely apply the European species name to the local fungus. This approach can easily lead to mistaken identities. DNA sequence data, on the other hand, is not subjective. Andrew Wilson, Ph.D., Assistant Curator of Mycology, explains, “As a result, mycologists such as myself have come to rely on DNA sequence data to inform our interpretations of mushroom species and see if the morphological descriptions and categories we’re using are actually correct.”

You can learn more about fungi in Colorado and neighboring states in the book Mushrooms of the Rocky Mountain Region, by Vera Evenson and Denver Botanic Garden.

All Photos: Scott Dressel-Martin, courtesy of Denver Botanic Gardens.

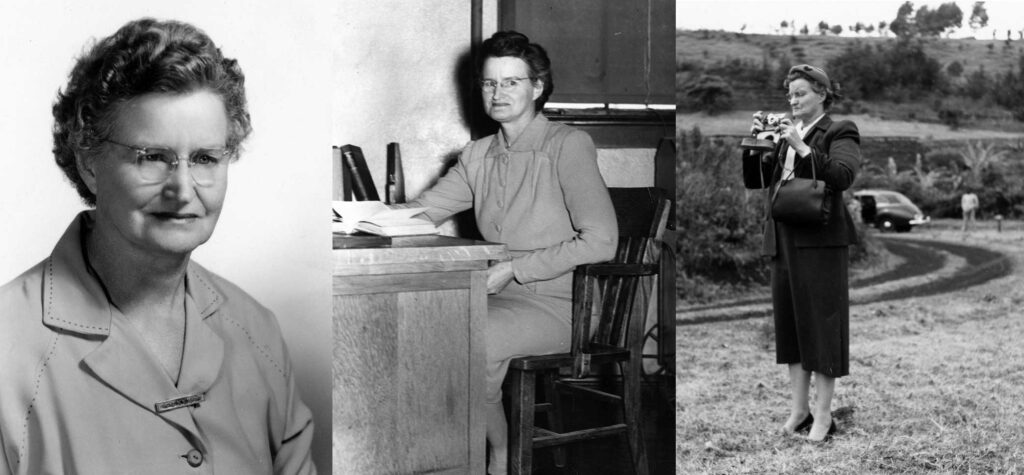

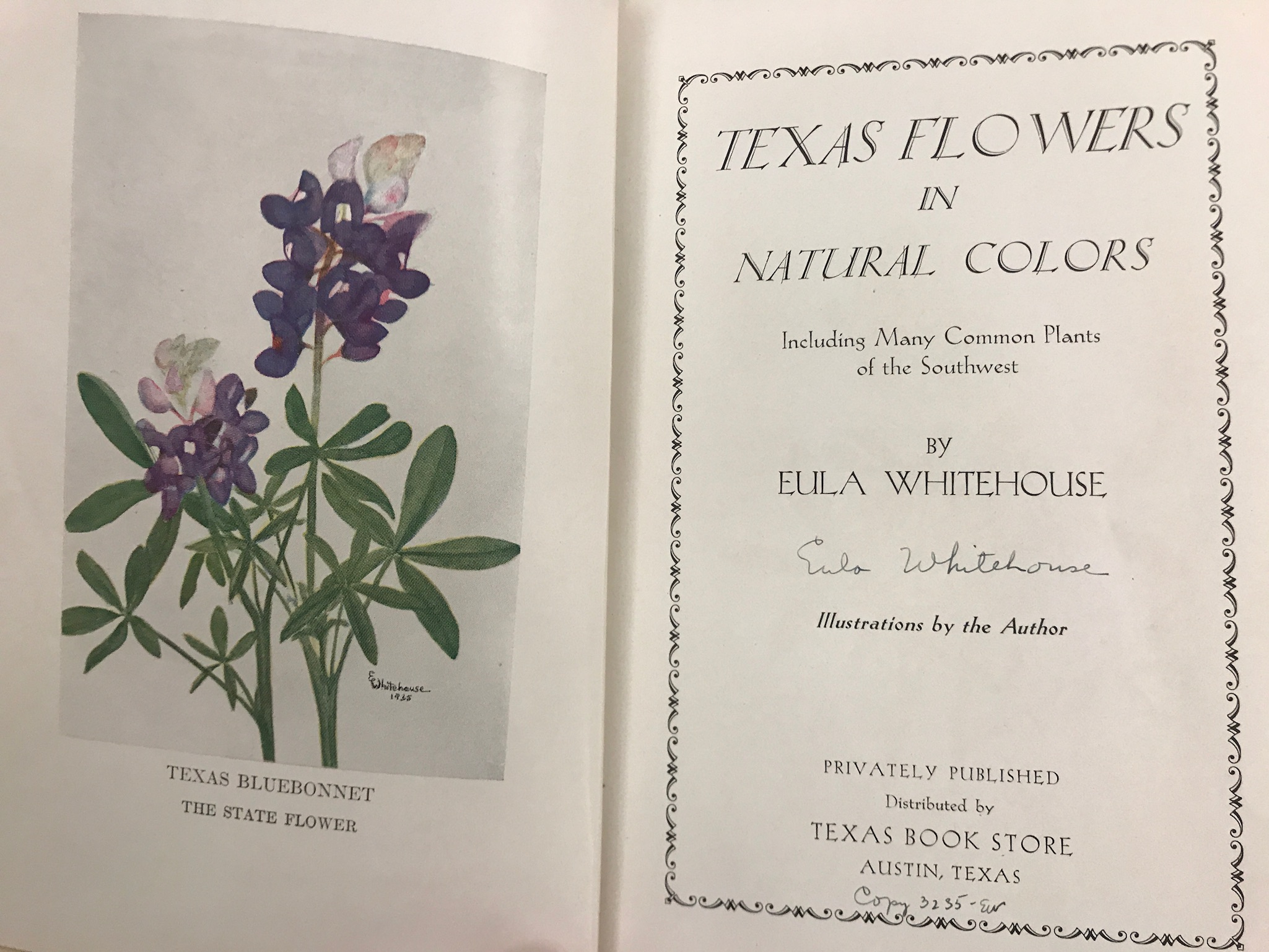

Eula Whitehouse and the Cryptogams

A gifted artist and well-rounded scientist, Dr. Eula Whitehouse was an incredibly accomplished botanist. And she achieved this distinction in an era when her advanced education (earning her Ph.D. in 1938) made her exceedingly rare among women. Though a well-rounded botanist, her fields of research were also unusual: cryptogams, a non-taxonomic term encompassing mosses, ferns, fungi, lichens, and algae, which all reproduce cryptically by spores. Southern Methodist University (SMU) Herbarium Director Lloyd Shinners recognized Eula’s contributions by awarding her the position of Curator of Cryptogams in 1954.

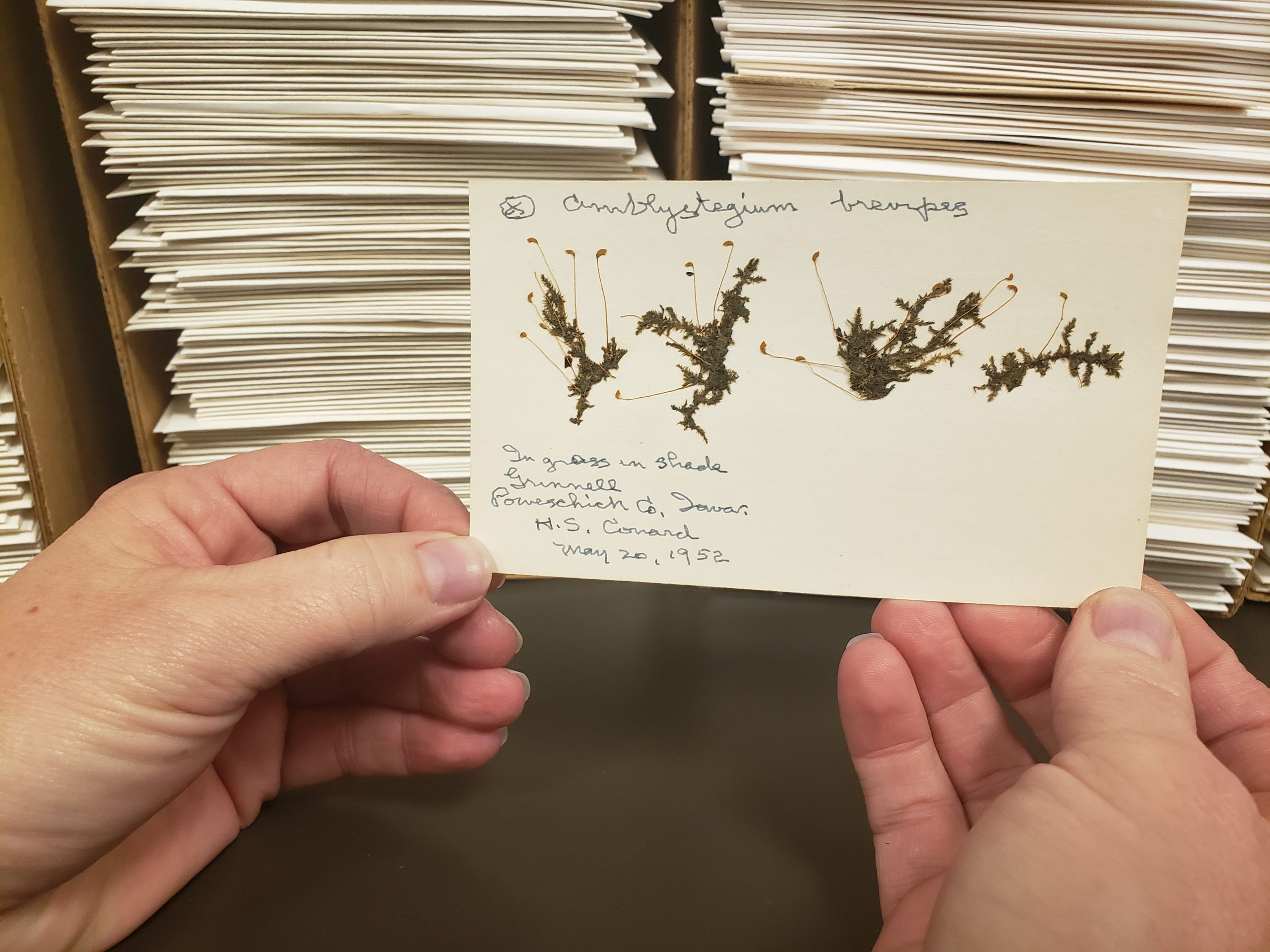

Eula’s botanical contributions while working at SMU have carried forward to the Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT). BRIT was established in 1987 to care for and house SMU’s extensive herbarium and botanical library. The collections include many of Eula’s drawings, six of her publications, her personal library, and thousands of her collected specimens. Her herbarium collections are particularly prominent amongst BRIT’s bryophyte collection.

During her tenure as Curator of Cryptogams, Eula traveled extensively. The mosses, liverworts, and hornworts to which many people pay no heed were often her targets. She collected mosses in Africa, traveled and collected in Hawaii, and studied mosses and liverworts at the University of Washington. In 1956, she engaged in a year-long, around-the-world botanizing trip. Her collections include specimens from Australia, New Zealand, Cyprus, India, Singapore, Fiji, and Mexico. And, of course, from Texas.

With the SMU botanical collection and Eula’s archive, BRIT inherited one of the best collections of Texas bryophytes, including vouchers for the The Mosses of Texas. In this work, Eula built on the early efforts of Frederick McAllister to list the mosses of the expansive state of Texas. McAllister’s work was largely based on the collection of the University of Texas Herbarium (TEX), which focused on southern and central Texas. Through her own collecting, Eula added much needed information on the mosses of northern, eastern, and western regions of the state.

In the foreword to The Mosses of Texas, Eula laments the general lack of research on the ecology of Texas mosses. This information gap continues to exist today for most bryophytes in the nation (and beyond). Being nonvascular plants, and thus lacking that supportive tissue, mosses (as well as liverworts and hornworts) are small and fairly inconspicuous; they can be overlooked, even by botanists. The bryophytes of Texas are still understudied and under-documented due to the sheer size of the state and the relatively few (though often dedicated) people searching for them. It is difficult to talk about conserving a group of plants without first knowing that there’s something to be conserved. Although BRIT does not currently have a bryologist on staff, the institute is committed to continuing the work of documenting bryophytes, making the specimens available through loans and visits, and putting digital collection records online.

Since Eula’s retirement, the BRIT bryophyte herbarium collection has seen a few fits and starts in growth. Eula remains the most prolific collector of existing specimens, with a total of 4,518 of nearly 16,000 at BRIT. Only 141 Texas specimens were collected in the 11 years following her retirement. The rate of collections picked up following the recruitment of William F. Mahler as Assistant Curator to the SMU Herbarium; in the next 11 years, the number of Texas specimens collected increased nine-fold. This growth in the bryophyte collection motivated Mahler’s publication of The Mosses of Texas: A manual of the moss flora with sketches in 1980.

Although most of BRIT’s bryophyte collection (75%) was collected in or before 1980, the collection is still growing and serving an important role for research. The current herbarium manager, Tiana Rehman, states, “I am not typically a collector of mosses, but I feel a duty to grow the collection in an informed way, especially when I see the care and impact Eula Whitehouse and Bill Mahler had on the collection.” And so she does, with the help of research associates such as Charles Gardener, partners like Dale Kruse of Texas A&M University Herbarium, interns, independent researchers, and others.

To increase the reach of the collection, most of the herbarium’s 16,000 bryophyte specimens have been digitized and made accessible to all through bryophyteportal.org as a reference for research. BRIT continues to make an effort to digitize their collections, imaging key specimens at high resolution and converting textual and graphical elements into a digital format that can more easily lend itself to data analysis and synthesis.

Many years ago, Eula Whitehouse worked in the field with her Exakta camera, one of the first single-lens reflex (SLR) cameras available. It was a far cry from the high-resolution cameras and light boxes used to digitize parts of her collection now, but the concept to document and share with others is the same. With her artistic eye, Eula created photos that were beautiful and worth sharing—even of those inconspicuous bryophytes. It is fortunate for bryophytes that this trailblazing woman of science brought her trail to them.

All photos: Courtesy of BRIT Library of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas.

CONSERVATION CHAMPION

Kristin Haskins, Ph.D.,

Executive Director,

The Arboretum at Flagstaff

Some people just can’t help it, they are natural born leaders. In a group where a job has been laid out, they are the ones who cut to the chase, volunteer, and do an excellent job no matter the task. Such was the situation when the CPC network decided to write Plant Reintroduction in a Changing Climate: Perils and Promises. Dr. Kristin Haskins leapt at the chance to co-edit the volume, ensuring that we did not forget to include a chapter about the importance of mycorrhizae for establishing healthy plant populations. Her great enthusiasm, exceptional writing and editing skills, and great determination to help others learn about applications of science to plant conservation proved invaluable to that book. For her continued unwavering leadership in plant conservation, we are happy to honor Dr. Haskins as the May 2020 Conservation Champion.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I was a late bloomer when it came to loving plants. Pun intended. Although I have always been fascinated with nature, my first love was with the animal kingdom. It wasn’t until after I finished my Master’s degree at the University of Kentucky that I fell in love with plants and their fungal partners.

What was your path to becoming the Executive Director at The Arboretum?

After ten years in Kentucky, where I received my Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in biology and animal behavior, respectively, I ended up working for The Nature Conservancy for a summer conducting plant surveys under powerlines. My budding interest in the plant kingdom inspired me to take more classes – this time in the field of forestry. It was in a dendrology class that I discovered the amazing relationship between plants and fungi called mycorrhizae. From here, I knew that I wanted to pursue a Ph.D. in plant ecology with an emphasis in mycorrhizal ecology, and this path lead me to Flagstaff and Northern Arizona University (NAU). I completed my Ph.D. degree at NAU in 2003, did a three-year post-doc, and found myself firmly rooted in Flagstaff and looking for work. The position at The Arboretum at Flagstaff opened up in 2006, I applied, and I have been here ever since then. My passion for The Arboretum and conservation work stems from my love of teaching something useful to others and applying research to saving plants.

Why do you believe it’s important, from a conservation point of view, to study mycorrhizal ecology?

Over 95% of known plant species in the world form mycorrhizal relationships of one type or another, so to not study this incredibly important relationship would represent a massive blight on our understanding of how plants interact with their environment. Besides, mycorrhizal fungi are really cool.

What has surprised you about studying these plant-fungi relationships?

Admittedly, I do not get to study mycorrhizal fungi and their plant partners the way I used to when I was a student, but something that I have always found fascinating is how these soil-borne fungi expand the connectivity of plants to their soil environment and beyond! Studies comparing individuals with and without their mycorrhizal fungal partners have revealed complex herbivore and pathogen interactions above and below ground, all impacted by the presence or absence of mycorrhizal fungi. And that is just the tip of the proverbial iceberg.

What current projects or approaches in plant research or conservation excite you most?

Life in the arid Southwest, be it animal, plant or fungal-based, is critically dependent on water. Some of the Southwest’s most endangered plants suffer from climate change impacts, such as extended and intensified drought, often leading to habitat loss and conversion. I have always been a huge fan of applied research, particularly when it comes to ways we can incorporate fungi into soil conservation. A friend and colleague of mine in the School of Forestry at NAU, Dr. Matthew Bowker, studies soil biocrusts, communities of living organisms (fungi, algae, bacteria, etc.) that form a crust on the surface of soils which, among many things, helps to keep the soil in place. Dr. Bowker’s laboratory group is researching ways in which soil biocrusts can be grown and applied to disturbed habitats to conserve the soil, and by doing so, conserve the plants that struggle to live there. To me, that is pretty darn exciting! Check out Dr. Bowker’s Research.

-

Kris at age 10, with a love for nature already instilled. She would turn from bunny hugger to tree hugger with time. -

Kris doing graduate work collecting root samples along a soil depth gradient. -

Kris helping The Arboretum team reintroduce the rare Autumn buttercup (Ranunculus aestivalis) in Utah. Just one of the ways The Arboretum works to save plants.

As Seen on CPC’s Rare Plant Academy

CPC’s Rare Plant Academy is one of the tools CPC uses to connect plant conservationists, amplifying their knowledge and experience to save plants. One part of the Academy is the Forum, where expert and novice plant conservationists can exchange questions and expertise online.

Earlier this year a member of RPA posted a question regarding treatment and storage of a Piperia species of orchid. Julianne McGuiness of the North American Orchid Conservation Center (NOACC), a CPC Participating Institution, consulted one of their key orchid experts for a detailed response. Orchids often need precise treatments for propagation and storage, and very little research has been done on the individual species in this large family. NOACC and CPC institutions are taking the lead to study some of the many U.S. species in need of conservation.

Julianne highlighted the importance of collecting roots from which orchid mycorrhiza fungi can be isolated, grown, and cultured for future use. Mycorrhiza are nodules of fungus that develop in certain plant roots, forming symbiotic relationships. These fungal associations are often key to successful germination studies, propagation, and restoration experiments. Their importance for orchids and orchid propagation add another layer of conservation and research need.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Ways to Help CPC

Support CPC by Using AmazonSmile

As many of us are now working from home and relying on home delivery more and more, we wanted to remind you that you can keep your home stocked AND SavePlants. If you plan to shop online, please consider using AmazonSmile.

AmazonSmile offers all of the same items, prices, and benefits of its sister website, Amazon.com, but with one distinct difference. When you shop on AmazonSmile, the AmazonSmile Foundation contributes 0.05 percent of eligible purchases to the charity of your choice. (Center for Plant Conservation).

There is no cost to charities or customers, and 100 percent of the donation generated from eligible purchases goes to the charity of your choice.

AmazonSmile is very simple to use—all you need is an Amazon account. On your first visit to the AmazonSmile site, you will be asked to log in to your Amazon account with existing username and password (you do not need a separate account for AmazonSmile). You will then be prompted to choose a charity to support. During future visits to the site, AmazonSmile will remember your charity and apply eligible purchases towards your total contribution—it is that easy!

If you do not have an Amazon account, you can create one on AmazonSmile.

Once you have selected Center for Plant Conservation as your charity, you are ready to start shopping. However, you must be logged into smile.amazon.com—donations will not be applied to purchases made on the Amazon.com main site or mobile app. It is also important to remember that not everything qualifies for AmazonSmile contributions.

So, stay safe inside, and when ordering online, remember you can still help save plants. Please feel free to share this email with your friends and family and ask them to select Center for Plant Conservation.

Thank you all for ALL you do.

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today