Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden

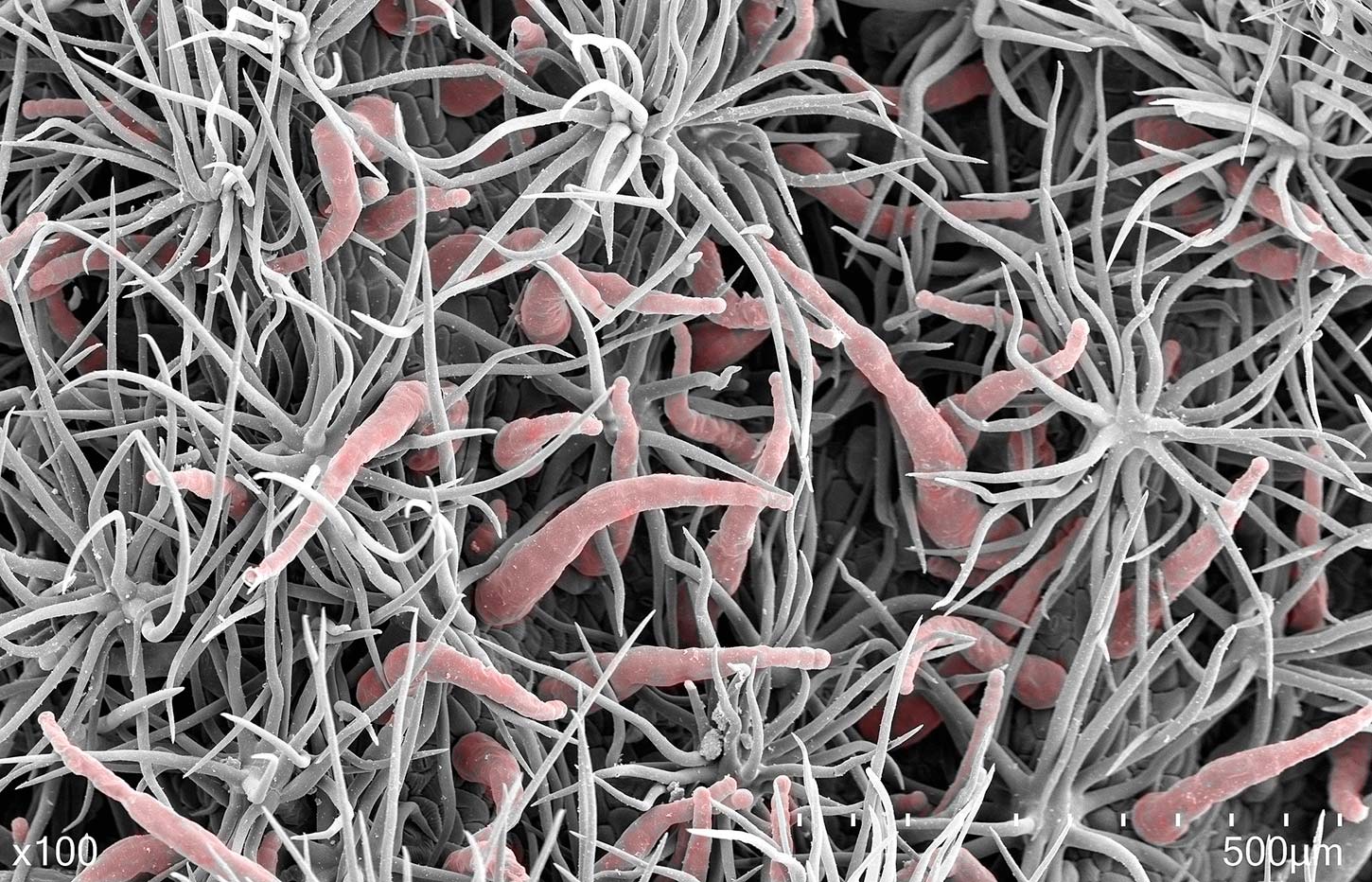

Heller’s bush mallow (Malacothamnus helleri), a rare species currently lumped in the more common Fremont’s bush mallow (M. fremontii). Keir’s research will help determine if M. helleri should be recognized as a separate taxon and thus retain its rare status or if it is just a minor variant of M. fremontii not distinct enough to warrant conservation status.

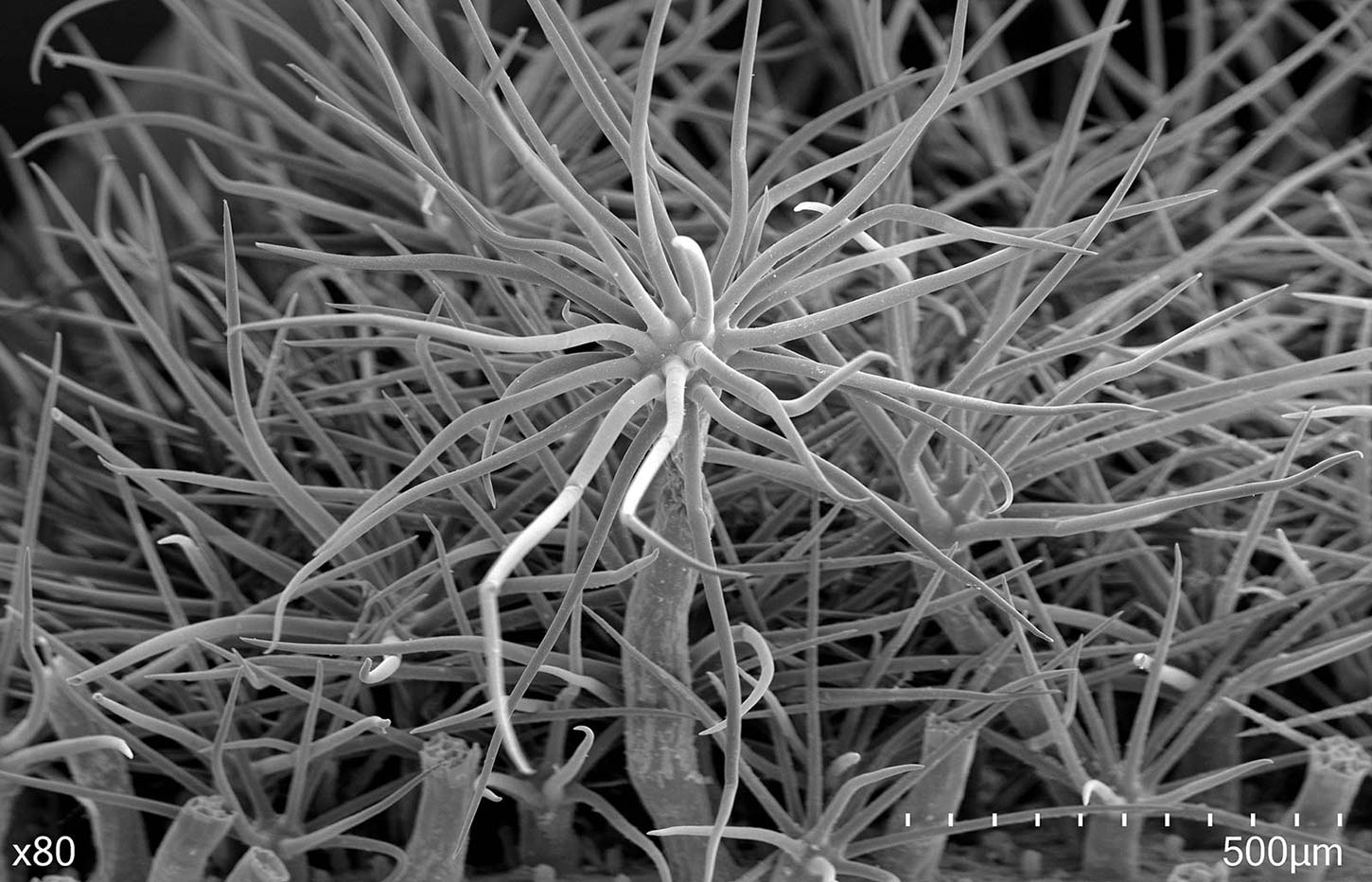

Coming across a set of beautiful pink to white globe-shaped flowers on a shrub with delicate star-shaped hairs on its leaves while hiking in San Diego might grab your attention. If you’re a botanist, you might be inclined to figure out what it was. You may recognize it as being in the mallow family (Malvaceae), or even as in the genus of bush mallows (Malacothamnus), but as you worked through your taxonomic key, you might run into some trouble. Field botanists quickly become familiar with taxonomic keys, working through the series of choices is the key to help them identify an unknown plant they have come across. These keys are important tools for conducting vegetation surveys, botanical surveys, and more but they can also have problems. Problems often stem from different approaches and results in the study of a group’s systematics (the classification and study of evolutionary relationships among species). Such was the case with keying out the Malacothamnus aboriginum found in San Diego County.

A seasoned field botanist, Keir Morse, was very aware of the keying difficulties with bush mallows in general and the taxonomic treatments, delineations, and descriptions of species. So, with the prompting and help of another San Diego area botanist, Tom Chester, Keir decided to look into the issue with M. aboriginum. The San Diego County populations were highly disjunct (not connected) to the more northern populations and had not been included in the previous studies of bush mallow morphology (physical features) that helped define the species. Conducting their own morphological study, looking at physical characteristics that are commonly measured, as well as new characteristics, they determined the San Diego populations to be their own species.

Keir knew there were issues throughout the genus: there are currently three different treatments of the genus in use, which conflict with each other. Emboldened by the success of the M. aboriginum work, he became interested in resolving the issues throughout the genus. To do so, he would need to learn more about how the lines between taxa (species and infraspecies, such as subspecies and varieties) are drawn and what information is needed to draw those lines – that is learn more about research in systematics. Working towards a doctoral degree at a place well known for their focus on systematics and floristics seemed like the next step and he soon found himself enrolled in the graduate program at Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden (RSABG) through Claremont Graduate University.

As he started this program, Keir quickly defined his project: to resolve the taxonomy of the genus, with an emphasis on the conservation questions. Systematic research is very important to conservation because deciding where species lines occur affects how rare those species are considered. The oldest bush mallow treatment to examine all named taxa recognizes 28 taxa in total, while the other more recent treatments recognize 11 or 17. Largely using the older treatment, the California Native Plant Society, through their Rare Plant Ranking system, recognizes 16 as rare. If some of these rare taxa are found to be just minor variations in highly variable taxa, then perhaps they should be lumped into these more common taxa and be delisted. This would allow any rare conservation resources going towards those species to be used on taxa more in need. Likewise, if some of the rare taxa lumped in the more recent treatments should be recognized, a new treatment needs to be put forth to easily identify what is rare and what is not. Better defined species lines that are easy to key out, are also helpful in determining what seed stock is appropriate to use for restoration or even landscaping. Using seed of a species from a different region could introduce hybridization problems. Tackling the species history and systematics is not just a botanical curiosity, there are conservation concerns tied to these results.

Keir is taking a total evidence approach to resolve the various issues within this complicated group of species. This means he’s not relying solely on morphological analyses, nor any other single type of data or analysis to make conclusions about taxon borders. Instead he is using a combination of morphology, genetic analyses, flowering time (a possible reproductive barrier), and extensive field evaluations to look at the larger picture.

Collecting all the data has presented its own challenges. All the field experience and time in the world does not help you find a species that simply is not showing up: many of these plants are fire followers (only germinating after fires) and then only live for a few years (3-20) before being outcompeted by returning vegetation. So it has been challenging to find plants in areas that have not burned. Here, the extensive resources of RSABG and other botanical institutions have been an enormous help to Keir. Herbarium specimens (many over 100 years old) can be used to measure some of the morphological characteristics of those populations that are now only dormant in a seedbank awaiting a fire or otherwise inaccessible. Though herbarium specimens can be used to provide DNA samples, the extractions can be difficult due to the degradation of the DNA. Fortunately, some of the herbarium specimens have seed which can be grown to new plants for high quality DNA extraction or seed is available in the long-term seed bank.

Also, aiding Keir in data collection is the online citizen scientist platform, iNaturalist. The pool of scientists and hobby naturalists across the range of the genus throughout California (and bits of Arizona and Baja Mexico) has helped Keir move past the difficulty of making multiple visits to all field sites to capture phenology. Over 1,000 people have contributed to his project, making over 2,700 separate observations. With thousands of observations, many locations have been found allowing for fresh specimen (including DNA) collection and more data to be taken.

Results thus far are pretty preliminary but also pretty promising. Keir’s keen observation skills helped him define a new characteristic for the genus, the fact that the flowers of M. fremontii dry open while other species dry closed, which has proven useful in distinguishing two similarly looking and occasionally lumped species that are also supported as different through genetic analyses. That the two methods support each other is encouraging. And so Keir continues mining iNaturalist (you can contribute, too!), spending hours in the herbarium or in the lab, and days in the field. He is confident that a clearer picture of this interesting group of mallows is forthcoming.

All photos Courtesy of Keir Morse, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden