Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

September 2019 Newsletter

Gone are the days…

when an organization could operate in its own silo, walled off from others in a competitive struggle to achieve. Today, collaboration is critical to success in most any endeavor, oftentimes affording the much-needed increase in outcomes needed to address the global challenges we face. While individual achievement remains critical, collaborative efforts have a way of elevating success on a much broader scale than operating alone. In this way, the Center for Plant Conservation has been functioning as a collaborative organization since its inception, collectively focused on saving plants – together.

The strength of CPC has always been its partnerships. In its founding, the central idea was – and is today – to bring together a wide variety of groups interested in saving plants so that all will learn, grow and become more effective at conservation. A testament to this is the value that the CPC National Meeting brings to our partners. The meeting and related events bring together our partners, fostering community, building collaborations and strengthening bonds – bonds that oftentimes become true friendships. In this way, the “CPC family” is truly greater than the sum of its parts.

This month’s issue of SavePlants is dedicated to the idea and ideal of collaboration. From multi-institutional initiatives that are working to save all of the plants of a state, to regional efforts to coordinate, document and save an entire flora, to national and international partnerships that work to learn and share what it takes to save plants, CPC partners work collaboratively to ensure conservation success. Read on to learn how these partnerships are making a real difference, measured in the numbers of plants saved from extinction.

Exceptional Collaborations to Save Exceptional Species

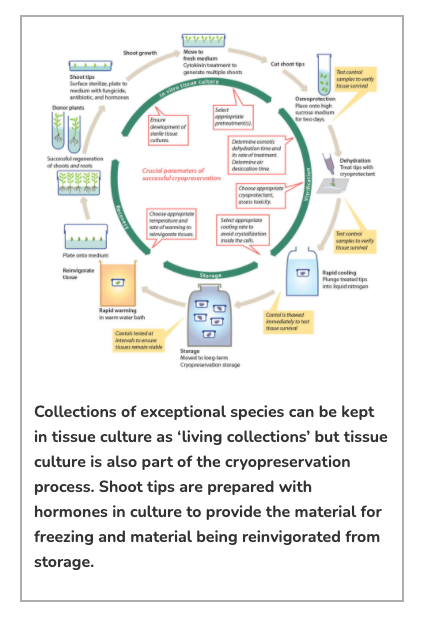

Nellie Sugii’s tissue culture facility at Lyon Arboretum in Hawaii has many of the same basic elements as the plant tissue culture lab at Cincinnati Zoo’s Conservation Research for Endangered Wildlife (CREW): both use artificial media in sterile tubes and jars to grow plants from tissue or seed. But upon visiting, Valerie Pence, Ph.D, Director of Plant Research at CREW, realized how different the labs were. The test tubes of plants Nellie and her team are grown with the goal of creating robust plants maintained as a living collection, which will be supported in subsequent generations by subculturing, or splitting the resultant plants into new plants. Valerie’s lab grows plants in tissue culture in order to get lots of shoot tips growing quickly, developing the material they need to cryopreserve the plants in liquid nitrogen (i.e., cryopreservation). While Nellie’s lab often forgoes use of hormones in the media supporting the plants to keep growth manageable, Valerie experiments with various hormones and changes to the media to find the right mix that rapidly promotes shoot tip production. The labs have different goals and thus different tissue culture techniques, but both methods are important in addressing the needs of many rare plants in Hawaii – and around the world – those known as threatened exceptional species (TEPs).

Tissue culture and cryopreservation can be used to support these TEPs to provide the same insurance as seed banking – providing plant material for research and reintroductions, and safeguarding a population as insurance. Seed banking has long been the cornerstone on which many plant conservation projects are built on, and yet, thousands of rare plants cannot be seed banked, hence they are the exceptions to the typical conservation approach. The challenges in fine tuning tissue culture and subsequent cryopreservation to the wide range of species needing them are great, and thus the plant team at CREW has been working to not only increase our understanding of these species but make sure more institutions are prepared to help conserve them. This project not only has CREW’s plant research team working with Lyon Arboretum, providing that very valuable insurance to the collections they have been keeping in tissue culture for years, but also has CREW collaborating with partners throughout the country.

CREW’s ambitious, multipronged project is being funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), as a primary goal helping botanical gardens learn more about and better maintain their collections. CREW is taking the lead in conducting research on identifying TEPs, promoting research within other institutions, establishing a network to build capacity and collaboration, and developing methods to conserve many Hawaiian TEPs held by Lyon Arboretum and understanding the genetic representation within those collections (with Dr. Theresa Culley’s lab at University of Cincinnati). They have enlisted eleven institutions as collaborating institutions to developing research questions and protocols for conserving their own TEPs, as well as various consulting experts (Dr. Chris Walters of NGLRP, Dr. Hugh Pritchard of Kew, Dr. Kingsley Dixon of Curtain University [Australia], the University of Cincinnati, and retired USDA staffer Dr. Barbara Reed). These collaborations form the basis of the Exceptional Plant Conservation Network (EPCN) to facilitate these projects and increase resources for all interested in working with TEPs.

The diversity of species being studied in the project is impressive: rare plants from the Pacific islands of New Caledonia and Palau, Colorado, Florida, and the northeastern U.S.; ferns, orchids and tree embryos; plants from deserts to swamps, mountains to prairies. The diversity has also meant that there is great variety in the approaches needed to work with them. For instance, the CREW staff working with the Hawaii species have met a few challenges when dealing with the variety in which the tissues grow and how they respond in culture to the different hormones. Postdoctoral researcher Megan Philpott, Ph.D., has taken the challenges in stride, stating: “It can be difficult to develop protocols for so many species at one time when there is very little information available about them but it’s been a fun challenge and we’re learning a lot about the responses of tropical species to cryopreservation.”

And everything they are learning is being shared with the larger EPCN – and vice versa. Members of this larger group, from the collaborating institutions from across the country (Atlanta Botanical Garden, Chicago Botanic Garden, Denver Botanic Garden, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Henry Doorly Zoo, Longwood Gardens, Missouri Botanical Garden, San Diego Zoo Global, and the Huntington Gardens), as well as some of the consulting collaborators came together last October. At the meeting, the collaborating institutions presented the research projects they are conducting with the IMLS grant seed money. The group will reconvene and share their progress within the year. And though the IMLS grant wraps up in 2020, the connections between these far flung collaborators and their work help to better understand what it takes to conserve exceptional species will continue.

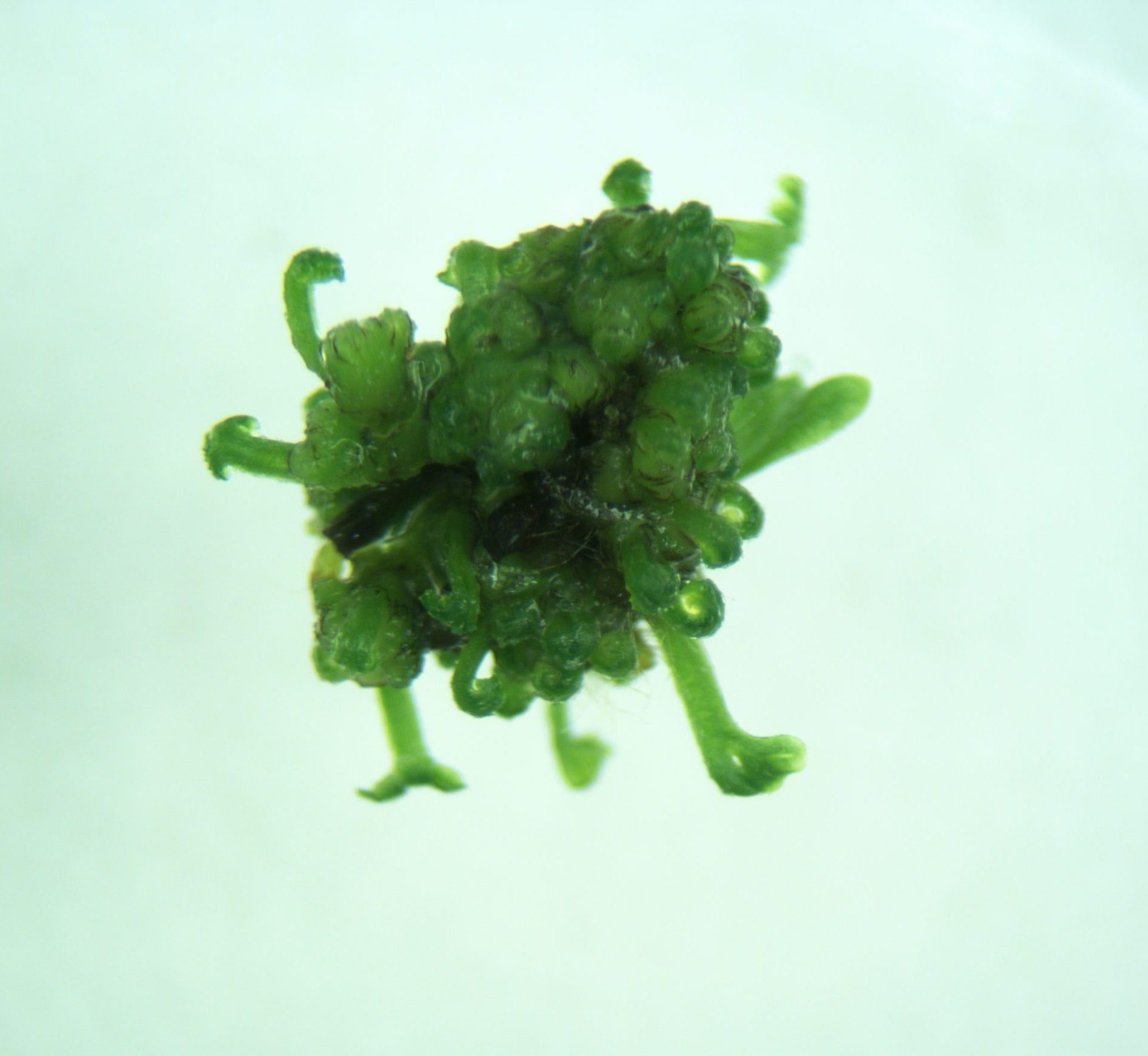

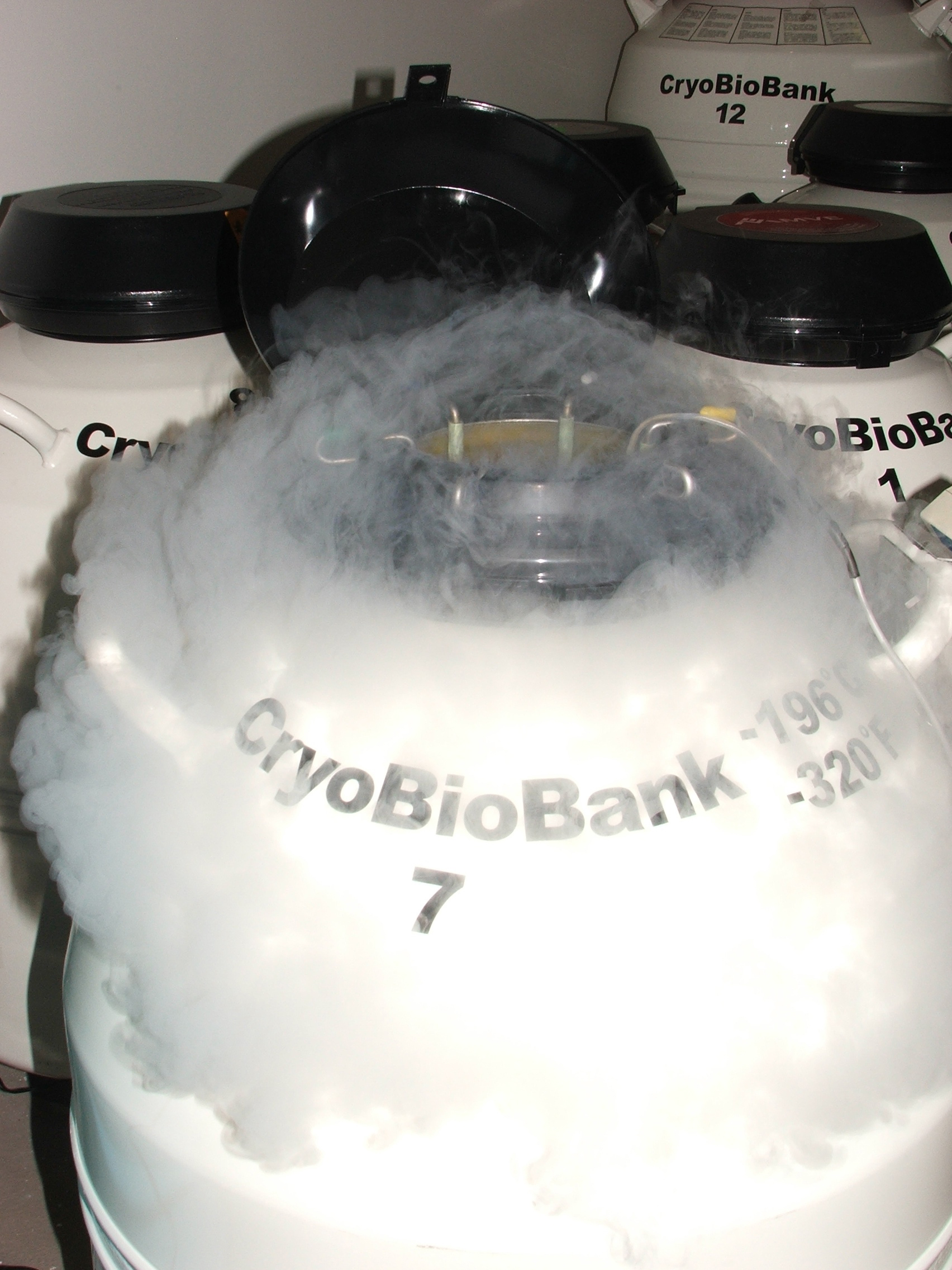

One of the many Hawaiian species CREW is working with is Asplenium peruvianum var. insulare, a federally endangered fern found on Maui and the island of Hawaii. Using the specimens of the fern kept in the sporophyte stage of its life cycle in vitro at Lyon Arboretum, CREW needed a game plan to cryopreserve it. Taking a page from their cryopreservation protocol for the endangered mainland fern Asplenium scolopendrium (American hart’s-tongue fern), CREW staff was able to produce green globular bodies (GGB), small clumps of tissue with multiple meristematic (cell dividing) regions, using media supplemented with plant growth regulators. After directly cryopreserving the GGBs using droplet vitrification, the team found an amazing 90% survival after exposure to liquid nitrogen! In addition, using GGBs has improved the efficiency of the cryopreservation process for this species, so it can more quickly and easily get many genotypes of the species into CREW’s CryoBioBank®.

Photos Courtesy of Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden.

Banking the Diversity of the Golden State

About six years ago, a curious graduate student decided to conduct a gap analysis of the conserved collections and the rare plants in California. Soon after, the CPC Participating Institutions within the state would be brought together to begin collaborating to fill the gaps.

The student, Nick Jensen, had a Research Assistantship at the California Seed Bank at Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden (RSA), a stronghold of rare plant seed collections in the state. Working with RSA staffers, Evan Meyer and Naomi Fraga, the team reached out to other seed bank institutions working in the state – largely other Participating Institutions in the CPC network – to better understand the collective progress to conserving the state’s unique botanical heritage. The published study pulled together data on over 500 rare plant seed collections. But with over 2,500 plants ranked as rare to some degree in the state, this impressive feat only amounted to 23% of these taxa. The collections did a bit better with the rarest of these (those rated as 1B – plants that are rare, threatened or endangered in California and elsewhere), having secured 30%, but still a far cry from the 75% established as a goal within the Convention for Biodiversity. The team at RSA realized a more coordinated and concerted effort was needed – and the seed for forming the California Plant Rescue (CaPR) collaborative effort was planted.

Fertilizing this idea, RSA connected with Dr. Peter Raven, Board Chair of CPC at the time, while at the Southern California Botanist Conference. Dr. Raven encouraged broadening the project to include not just the seed banks RSA had contacted to collect the initial data but also other CPC Participating Institutions and those working to join CPC. The broad set of collaborators across the state, which now includes CPC, California Native Plant Society (CNPS), East Bay Regional Park, San Diego Botanic Garden, San Diego Zoo Global, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, University of California Botanical Garden, University of California at Davis Arboretum & Public Garden, University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), and University of California at Santa Cruz Arboretum and Botanic Garden, came together under a Memorandum of Understanding in 2015 with the ambitious goals of meeting the Convention for Biodiversity goal and, more broadly, conserving all of the diversity of the state and the California Floristic Providence.

Since then, the group has made great strides, both tangible and intangible. Annual meetings and regular conference calls keep the group in touch and increase the opportunities for learning and collaborating. The group has pooled their data, again, but this time in a database accessible to each of the partners and readily updatable. The public, and land managers, can search a lite version of the database through the collaborative group’s website as well. CaPR has come together for workshops, presentations, developing outreach materials, seeking funding opportunities, and more. Significantly, the past few years have seen an increase in the rarest species being collected, and along maternal lines, for conservation. As of the 2018 collection season, the group has collectively saved 46% of California’s 1B ranked species in seed banks. An additional 13% are found in CaPR partners’ living collections.

Whether or not the group reaches the 75% goal may quite literally depend on the weather. A good year for the native plants in 2019 promises to convert to a great collection year. Regardless, California is well situated to ensure that its botanical treasures are secured in good time.

The initial gap analysis provided some further insights on how to strategically move forward. Through the analysis it was clear that species protected by the federal endangered species act (ESA), or even the California ESA, had much better odds of having already made it into collections. Clearly, the funding mechanisms already in place to help listed species had helped these species meet this conservation benchmark. The remaining 850 or so of the 1Bs had no such support. Until recently.

This summer started with some excellent news for the unlisted rare taxa, and the flora of California in general: the approved state budget includes $3 million to be spent over five years to support the seed collection and banking of the 1B plants in the state. This conservation boon was the result of the quick mobilization for advocacy of CaPR member, the California Native Plant Society (CNPS) to enable the California Biodiversity Initiative. The initiative was spearheaded by Governor Jerry Brown (and supported under his successor, Governor Gavin Newsom) and the biodiversity experts they gathered, to “secure the future of California’s Native Biodiversity”.

The CaPR group has high hopes that the funding allotted in the budget will be allocated in a way that will help them secure California’s flora. To guide their collection priorities, they are currently working on a new gap analysis, one that builds on their newly developed tools, as well as phylogenetic and spatial data. With the new gap analysis tools, CaPR will be able to prioritize the collections using criteria critical to each institution and target new lands to get access and permission to collect. Between the new gap analysis and their previous endeavors as a group, CaPR is well prepared to conserve the amazing floral treasures of the Golden State.

Saving Smooth Coneflower in Oak-Hickory Glades in Georgia: A Twenty-Five Year Partnership

This year marks the twenty-five year anniversary of my love affair with smooth coneflower (Echinacea laevigata), a federally listed endangered wildflower endemic to the southeastern United States. I was introduced to smooth coneflower by the Georgia Plant Conservation Alliance (GPCA) as a beginning graduate student in horticulture. I needed a thesis project, and smooth coneflower needed help.

The GPCA is an influential network of conservation professionals who collaborate in hands-on rare plant conservation work. Founded in 1995, the GPCA took on smooth coneflower among their first priority projects. They chose to work on smooth coneflower, not only because it was in serious decline, but also because, for the first time, each of the key partners for its conservation were committed to work together. Landowners, restoration ecologists, forest managers, botanists, horticulturists, and permitting agents all sat around a table to devise a plan. They continue working together in this planning process for smooth coneflower, and many other species, to this day.

Smooth coneflower recovery in Georgia has been successful because of the strong partnerships between key organizations. Each partner contributes expertise that only they can provide. In the case of smooth coneflower, the US Forest Service owns and manages the land, the Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Conservation Section monitors the plant community’s response to the management, the State Botanical Garden of Georgia grows the plants, and Atlanta Botanical Garden (a fellow CPC Participating Institution) maps the plants and manages a database of many of our project records.

Helping a rare species recover from precipitous decline, as with smooth coneflower, requires the cooperation of different entities on several fronts. The first step with smooth coneflower was for the landowners, Georgia Power and the USDA Forest Service, to protect the existing populations from herbicide and road grading. Because it requires open sunny conditions, this special plant was only persisting on roadsides and power line rights-of-way where it was vulnerable to maintenance activities. But soon after smooth coneflower’s federal listing in 1995, both landowners designated the plant sites as special management areas, effectively protecting them from herbicide and grading damage.

Next, partners in the USDA Forest Service worked tenaciously to change forest management practices to return the plant community to its pre-Columbian condition, an Oak-Hickory Glade favored by smooth coneflower and many other plants unique to the habitat. The management regime includes judiciously removing trees to thin the canopy, eliminating shrubs, and implementing prescribed fire. The plant community restoration has been a slow process from our human perspective, but worth the effort and wait. Recently the plant community has begun to settle into a balanced grassland community, complete with a matrix of native grasses, and many prairie wildflower species like blazingstar (Liatris spicata), indian pink (Spigelia marilandica), square heads (Tetragonotheca helianthoides), wild quinine (Parthenium integrifolium), salvia (Salvia azurea), butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa), rattlesnake master (Eryngium yuccifolium), American aloe (Manfreda virginica), and with a little help, smooth coneflower.

-

James Sullivan, independent botanist, has been involved with smooth coneflower conservation since day one. Photo credit: Heather Alley, courtesy of SBGG. -

The extremely rare pine snake’s return to the region has been credited to the habitat restoration efforts implemented to support smooth coneflower. Here Clemson University graduate student Brian Hudson holds a male pine snake. Photo credit: Patrick Ceska. -

Field of smooth coneflower (echinacea laevigata). Photo credit: courtesy of State Botanical Garden of Georgia.

Meanwhile, the State Botanical Garden of Georgia has worked to increase the numbers of smooth coneflowers in each of the largest five populations. In initiating this process, I was recruited to research methods for reintroducing smooth coneflower into the wild. I was able to learn from expert conservation horticulturists at partner gardens: Atlanta Botanical Garden, North Carolina Botanic Garden, and the Chattahoochee Nature Center who had experience growing smooth coneflower. Atlanta Botanical Garden provided plant material for my research – saving me an entire growing season! My master’s thesis demonstrated that successful reintroduction of smooth coneflower was not only doable, but relatively easy compared to other plant species.

After completing my thesis I was no longer regularly involved with coneflower but I never forgot these special plants. Ten years after my experimental reintroduction, I was traveling in the area and decided to check to see if any of the smooth coneflowers still persisted. I was stunned to find the once bare ground blanketed in grasses and the smooth coneflowers – fully grown and heavy with flowers. I jumped back on the bandwagon, and have been growing crops of smooth coneflowers almost every year since then.

It is great to be back working with the dedicated group of partners. Our smooth coneflower team meets in the field every year to do maintenance, plant new individuals, and monitor. Many of us have been working together for decades now and we consider one another family.

Michael Way

As the Conservation Partnership Coordinator for the Americas, Michael Way is the representative from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, that the majority of CPC institutions are most familiar with. He has collaborated with and supported many of the Participating Institutions’ seed banks for decades, and continues to support seed banking across Canada, the USA, Mexico, and Chile today.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I grew up surrounded by beautiful landscapes of the Exmoor National Park (in the south west of England) and was interested in all aspects of biology and the natural world but my love for plants was equaled by concerns about their future. As a second-year biology student, I found a summer job helping the National Park botanists monitor the response of heathland vegetation to grazing and burning management. I quickly realized that I could reliably identify the heathland flora and I could use quadrat data on plant populations to contribute evidence critical for large scale management decisions. I then studied the dormant rhizome buds of the bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) for my final dissertation and could clearly demonstrate why this species is so resilient to eradication efforts, at this point I was hooked on the application of plant science for decision-making.

What was your path to becoming the Conservation Partnership Coordinator?

After university, I worked on habitat survey and conservation work with landowners in Somerset and Hampshire, and I had great mentors who inspired me to continue working in nature conservation. But I wanted to explore Latin America, so I studied Spanish in the evenings and found a volunteer role with a conservation and education group in Ecuador. There I worked developing their small native tree nursery, leading practical conservation work tasks, and supporting educational projects. On my return to the UK, a job came up as Kew’s ‘seed collector for the Americas, and I had to give it a go. The expeditions were long and arduous – and allowed Kew to develop new ways of working with counterparts under the Convention on Biological Diversity. In 1995, I was asked to help plan the Millennium Seed Bank Project’s (MSB) international program, and I persuaded colleagues to invest in local and regional partnerships to scale up the global efforts. I was excited to take one of the coordinator roles that opened up at the new MSB. Almost two decades on, there have been lots of changes in the scope and name of the role, but I continue to be focused on Kew’s plant conservation work in the Americas.

What about working with plants has surprised you?

As a student it seemed that the zoologists might be having more fun, but plants have not disappointed! As my work has expanded in scope internationally, I am still amazed at the number of new species described each year, including a 130 feet tall tree described in 2016 from Cameroon. There is still urgent need for botanical exploration before such species are lost without being studied. In Britain, we have a modest and well recorded flora but there are still surprise records every year and regular monitoring efforts are showing the effect of introductions, wider land-use changes and the warming climate – so we need to keep up our botanical efforts, too.

What has been the most challenging aspect of your work?

Much of my work at Kew has focused on building capacity for conservation, and the biggest challenge has probably been to sustain this capacity between individually funded projects. To have long-term impact within an institution or region, I seek commitments from managers to continue the investment in the facilities, equipment, and people needed to maintain effective plant conservation teams. We certainly have to be increasingly creative in our project designs and think of low-cost ways to develop networks, improve technology, and help people both develop careers and get access to best current knowledge on how to conserve plants.

How have collaborations helped you succeed in your conservation programs?

Collaboration is central to my role, and it has enabled Kew and its partners to make huge gains in ex situ plant conservation, through the almost two decades of the MSB Partnership. The best collaborations reflect shared strategic priorities and take into account the needs and constraints of each partner through good communication and planning. By enabling the MSB Partnership coordinators with some real flexibility to seek cooperation with botanic gardens, universities, government agriculture and forestry agencies, as well as gene banks, there are now over 160 partners in 96 countries and territories contributing to the MSB Partnership’s global seed banking. We are still adding new partners: I have just started a novel collaboration with the National Institute of Health in Peru to seed bank medicinal plants from the high Andes. They bring a completely different set of skills and approaches to our projects.

What new approaches in plant conservation and science excite you the most?

Plant collectors have always done careful preparation before going into the field, and the technology that has matured in recent years is already impressive. We are routinely using predictive mapping to identify potential target species occurrences, and I am particularly excited with the potential of the MSB Partnership desiccation-tolerance predictor tool which is helping us focus collecting effort on the ‘bankable’ species, and research effort on the uncertain taxa.

Fieldwork is relatively costly and I am assessing the latest genetic diversity sampling models to make our collecting efforts as effective as possible, while ensuring our samples have sufficient diversity as a foundation for restoration or recovery projects.

Looking to the future, I am sure that our skills to recognize and handle germplasm from exceptional species will significantly improve, and the knowledge of when to deploy cryopreservation and other ex situ options will be strengthened. And as a recent ‘iNaturalist’ member, I can’t ignore the huge potential of citizen science to engage a larger community in botany and plant conservation.

Photos Courtesy of Kew America.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today