Whited’s milkvetch (Astragalus sinuatus) is found only within a ten-square mile (26 sq. km) area in central Washington. Although much of the historic range of this species has been converted or destroyed by agriculture and grazing, there is quite a bit of suitable habitat remaining. Scientists do not know why Astragalus sinuatus has not spread to these areas of seemingly suitable habitat. Whited’s milkvetch presents quite a challenge to researchers and seed conservationists. The seed pods of this species are small and incredibly tough. It may take a pair of pliers to crack the fruit open and extract the seed. For all the work involved, the pods have only one or two (rarely more) seeds inside (and sometimes they are completely empty). In the wild, pods open at one end, releasing seeds as they shake in the wind or roll down the hill. Often, the pods are so tough that they do not open until weathered and rolled along the ground. Despite the tough pod, the seeds often fall victim to seed predation or larval damage. Certain insects can bore a tiny hole through the pod and the seed coat and deposit an egg within the seed. As the larvae develops it consumes the contents of the seed. (From CPC website)

Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

September 2017 Newsletter

If you think in terms of a year, plant a seed; if in terms of 10 years, plant trees; if in terms of 100 years, teach the people. – Confucius

With over 4,400 rare and endangered plants in North America and 80,000 plants facing extinction world wide, it seems as if we could never sow enough seeds or plant enough trees to save them all. But through our efforts in teaching others about plants, there is great reason for hope. This month’s issue of Save Plants is dedicated to all the educators in our ranks and the students they teach.

The Center for Plant Conservation is dedicated to advancing the science of saving plants and by sharing new and improved ways to bank seeds, grow plants and conserve their vital genetic diversity. We teach one another how to save as many kinds of plants as possible. Whether it is in a formal classroom setting where students earn credit towards degrees in plant conservation, or through on the job training, down in the dirt with the plants we work to save, CPC scientists around the country share what they have learned and know with others.

It is this commitment to education that enables us to save more plants than we ever could otherwise. And it is this direct effort to bring in more people to do this work that allows us to continue saving more plants each year.

Read on to learn more about some of these efforts to teach and inspire. This commitment to others, and our planet, I trust will inspire you too.

Cornell Botanic Garden has a variety of programs for children in grades K-8. In the International Crop Garden, for example, children learn about the different plants that feed people all over the world. In another program, the children explore and learn about native wildflowers. Using native wildflowers, the students learn about life cycles, the ecology, and botany of those plants – basic plant science. And we can’t forget about trees – in one of the programs offered, students learn to identify trees and even get to take core samples.

Undergraduate and graduate internships are also available. The summer internship program aims to build on classroom learning by providing hands-on experience in many aspects of plant science, from plant identification to learning more about native plants, collecting seeds from rare plants to learning more about preserving natural areas. The internship programs are open to all majors. One of the internships is specifically reserved for a non-plant science major. You can learn more about the experiences of some of the interns here.

Learn more about K-8 programs at Cornell Botanic Garden here and internships here.

Photos courtesy of Cornell Botanic Garden: Rayleen Ludgate, the Youth Education Coordinator, takes all local 3rd grade school children into the Mundy Wildflower Garden each spring to teach them about native wildflowers. The second photo is one of the volunteer docents, Susanne Lorbeer, who is leading a plant identification walk for Cornell students.

The University of Washington Botanic Gardens has several programs for teaching young aspiring scientists. Many of the sessions build on each other so that young students can develop an understanding of the basics. For example, the Plants 101 session teaches students how to categorize, to collect data and how to “compare and contrast” different parts of plants. Plants 201 digs deeper by looking at specific functions of the parts of the plant. There are sessions on wetlands and on forests, as well. Find out more about the programs for young students here and here.

Internships for college students are also available. The University of Washington Botanic Gardens offered two types of positions for interns this past summer. One was the “Nitty Gritty.” Interns worked in areas such as plant health care, planting, new plant care, mapping and plant records, and plant collections. The second type of internship position was “The Whole Enchilada.” In this internship, the student was introduced to all the areas of the botanic garden such as horticulture, plant records, herbarium, and research.

Another program where graduate students can get hands on experience both in the lab and in the field, is the Rare Care Research program which supports restoration of plants listed under the Endangered Species Act. More information on the Rare Care Research Program is available here.

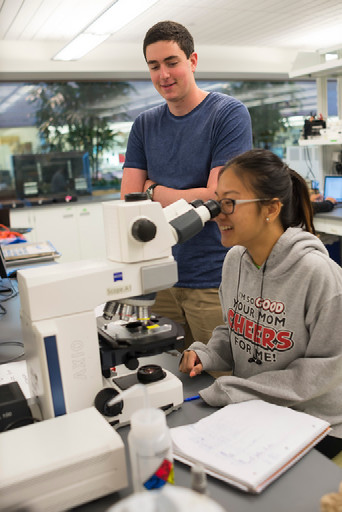

Photos courtesy of University of Washington Botanic Gardens.

Education for young people doesn’t occur only at Participating Institutions located at universities or colleges. The Chicago Botanic Garden has a program called College First. This internship is designed for Chicago public high school students. The program provides career mentorship, work in field ecology and conservation science. These high school interns work in areas such as plant genetics and seed biology lab, seed banking, and conservation biology. Some of the research projects that students have worked on include identifying native bee pollinator species of native plants, stratification and seed germination of a specific plant, and invasive species and how to treat them.

Chicago Botanic Garden also offers a ten-week internship – Research Experiences for Undergraduates program (REU). This program allows students to explore different scientific fields in plant biology and conservation. Some of the 2017 research included: “The importance of ex-situ conservation,” “Testing the frost tolerance of seedlings along a latitudinal gradient,” and “Local adaptation of flowering phenology in common milkweed.” You can find videos of the students’ research here.

Or students might want to try the Conservation and Land Management program (CLM) internship. This is for college graduates who have worked in biology-related fields. The program is partnered with several federal agencies, including the Bureau of Land Management, and with non-profit organizations such as several of our PIs (North Carolina Botanical Garden, Rae Selling Berry Seed Bank, and the New England Wild Flower Society).

Photos courtesy of Chicago Botanic Garden

Photos of Students and Interns at Chicago Botanic Gardens

Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden offers BioTech High School. This program gives high school students a STEM education, focusing on botany and zoology. Students have the “unique opportunity to research the natural world, develop questions and be a part of their solution.” You can read more about this program in “Can Young Botanists At A Magnet School Play A Vital Role In Protecting An Urban Ecosystem?”

The Arboretum at Flagstaff works with the Navajo Nation’s Fish and Wildlife Natural Heritage Program to offer internship opportunities. The Navajo Natural Heritage Program goal is to create a Navajo Native Plants Program that would focus on “collecting, banking, and propagating plant species important to ecological diversity, restoration, and culture.” Their goal is to create a seed banking program where collected seed can be used to grow “genetically-appropriate restoration, rare, and culturally-important plants.” Interns complete 15 weeks training in “wild-land seed collection and cleaning, plant propagation methods, greenhouse operations, ethnobotanical plant identification and uses, and interpretation techniques for public audiences.”

Photos courtesy of the Arboretum at Flagstaff

Why is the Navajo Natural Heritage Program important, what are culturally important plants, and why are they important? Nora Talkington, botanist at the Navajo Natural Heritage Program answered: “I think natural heritage programs are important because they allow us to track the status of rare and sensitive species at both a local scale (within a single heritage program) and at a larger scale (between heritage programs), regardless of political boundaries. I think it’s really important, when thinking of how best to conserve a species, to have both a local viewpoint of how the species is doing within a particular region and also a larger sense of how it is doing across its entire range. The Navajo Natural Heritage Program was established in 1984 and is very unique because it’s the only Native American-based heritage program.”

“Culturally-important” plants are species that have particular significance to the Diné people from an ethnobotanical standpoint. These are plants that are currently or were historically used as food resources, for clothing or basket-making, dyes, medicines, or ceremonies. One goal of the Navajo Native Plants Program is to increase community access to some of these culturally-important species by collecting seed and propagating these plants, especially species that are currently difficult to find on Navajo land.

The program will have a better idea about which of the species are good candidates for propagation later this fall/winter after they visit chapter houses and talk to community members about traditional and current uses of native plants.” Talkington went on to say, “A good plant to highlight is Three-leaf sumac: Rhus aromatica var. trilobata. This is an important Navajo plant for basket-making, as a food source, and in ceremonies. Another good plant to highlight is banana yucca: Yucca baccata, which was traditionally a really important food source for the Navajo.” Talkington shared the Navajo legend associated with the creation of the yucca:

The Slayer of Alien Gods, a culture hero of the Navajo, upon slaying the Tracking Bear Monster, told him that, as he had been bad all of his life, upon death must furnish sweet food to eat, foam for cleansing, and thread for clothing. The Slayer then threw a piece of the Bear’s head to the west where it became Yucca baccata, whose fruit is edible. Another piece he threw to the south, and it grew into Maguey (Agave utahensis), which is used for fiber.” (From the Ethnobotany of the Navajo)

Whited’s milkvetch (Astragalus sinuatus)

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today