Seed Banking in Hawai’i through Changes and Challenges

Since its founding by Alvin Yoshinaga in the early 1990s, the Seed Conservation Lab at Lyon Arboretum has strived to serve as the ex situ conservation center of native Hawaiian plants — especially threatened and endangered species — through seed banking, propagation, research, and education. This important work is done in partnership with the arboretum’s Micropropagation Lab and Rare Plant Greenhouse, under the Hawaiian Rare Plant Program.

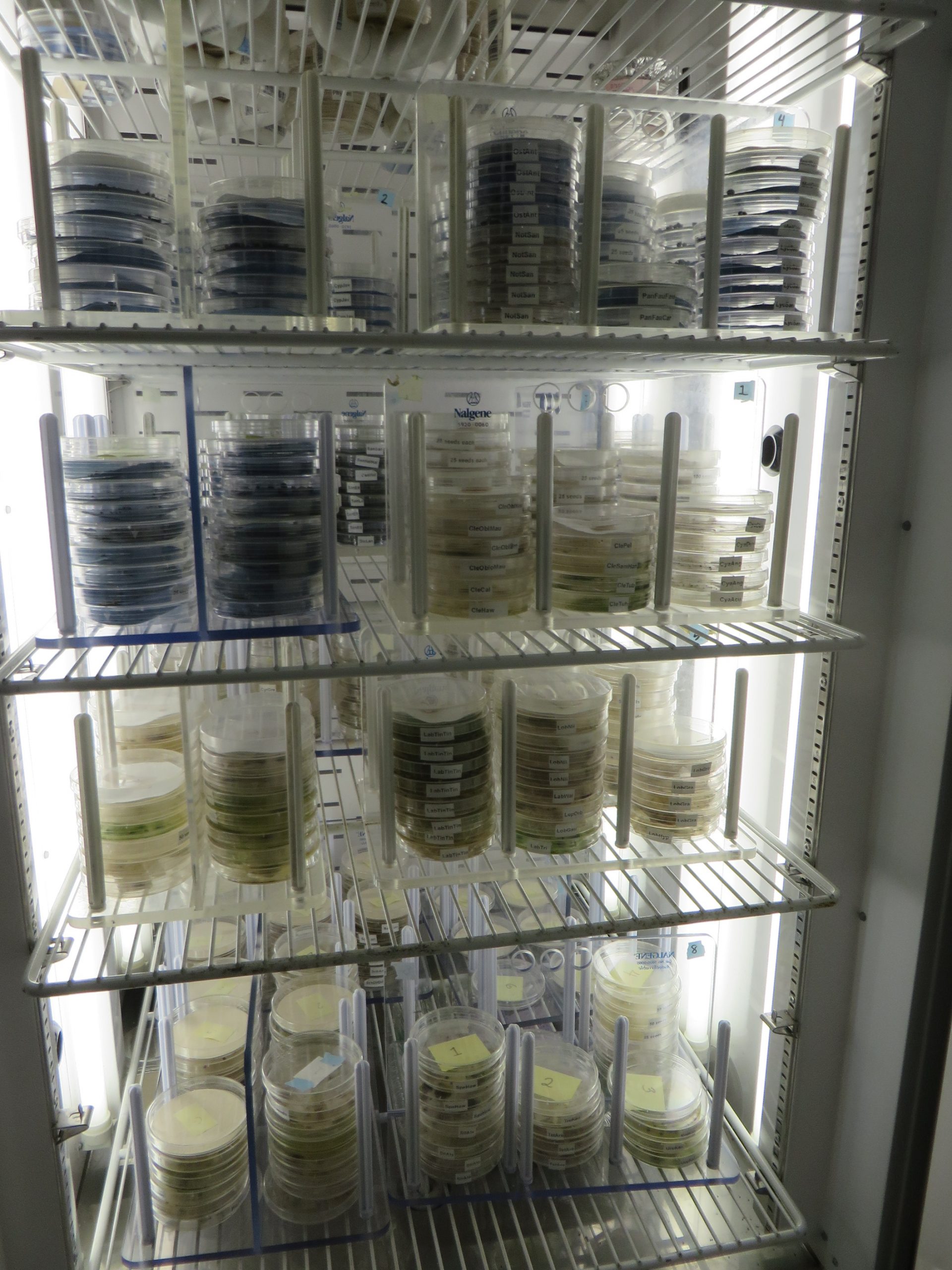

Through the efforts of many previous staff and our conservation partners, we currently hold about 28 million seeds from over 600 species, about half of which are threatened or endangered. About half of those are species that have fewer than 50 plants in the wild. We even have seeds of 10 species that are extinct in the wild.

Seed banking is the most efficient method for ex situ conservation when seeds can be stored using conventional seed banking methods, keeping them dry and cool. Seeds take up much less space than living collections and require much less maintenance once they are processed and stored properly. Although Hawaiʻi is the endangered species capital of the world, the fact that seeds of many of these threatened and endangered species can be stored under conventional seed banking methods really helps us buy time to rescue many disappearing species.

-

Seeds of the endangered species Haha (Cyanea copelandii subsp. haleakalaensis) a vine-like shrub endemic to Hawai'i. -

The seed photos provide a close-up look of the textured seeds of Pua kala, Pōkalakala, or Hawaiian prickly poppy (Argemone glauca var. decipiens). -

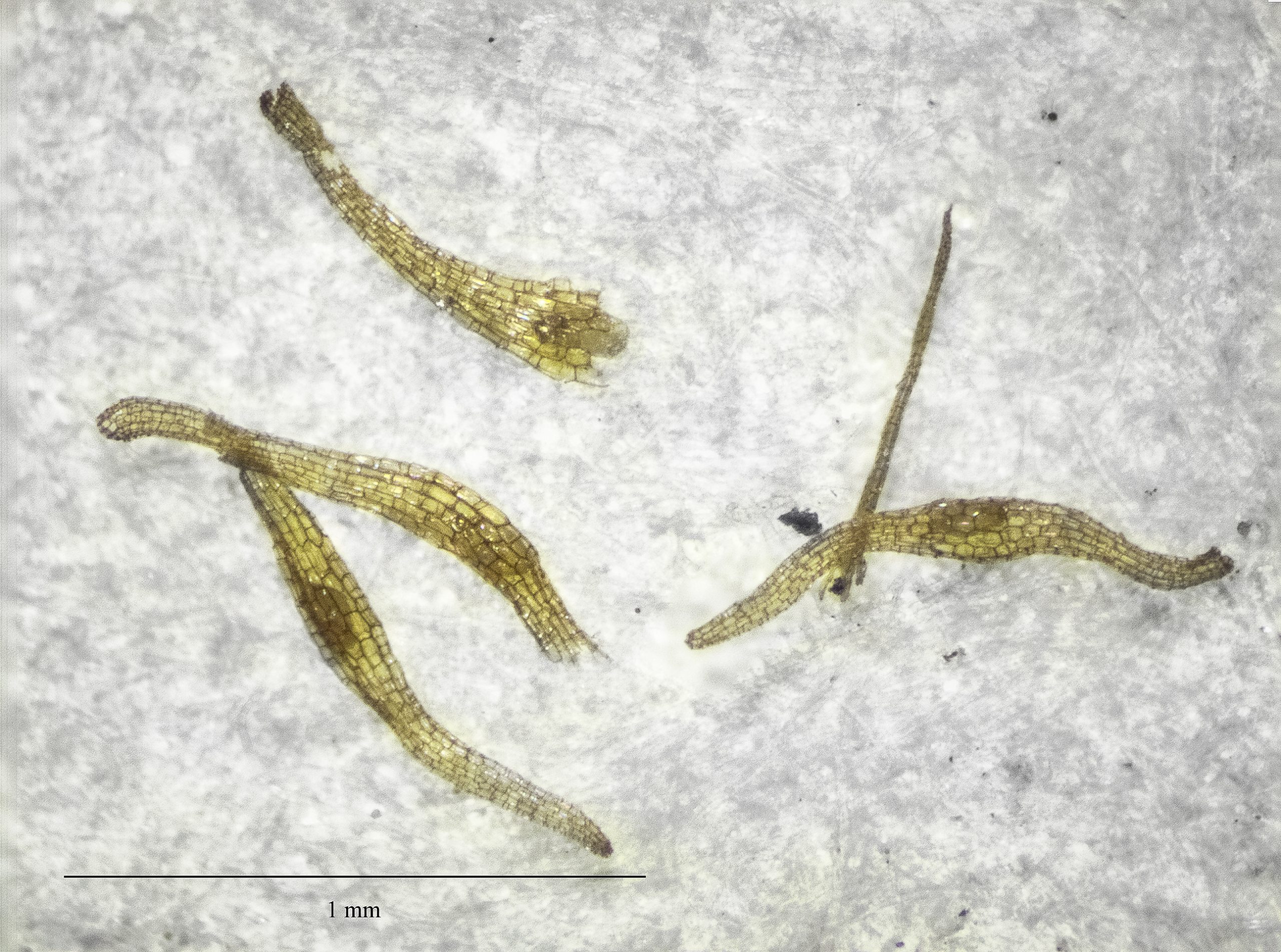

Lyon's collection includes the miniscule seed of Honohono, or Hawaiian Jeweled Orchid (Anoectochilus sandvicensis).

Because Hawaiʻi is so remote from the rest of the world, many species either had to arrive here after a long trip by air or water, or evolve here. This placed a strong selective pressure on seed physiology in native Hawaiian flora. When I first learned about it, I became quite intrigued and hopeful. Having a background in tropical ecology in the Neotropics, where many seeds do not possess dormancy (a prerequisite for seed banking), it was always a race against time before seeds I collected would go bad or germinate. Seed banking was not something I could take for granted with tropical plant species.

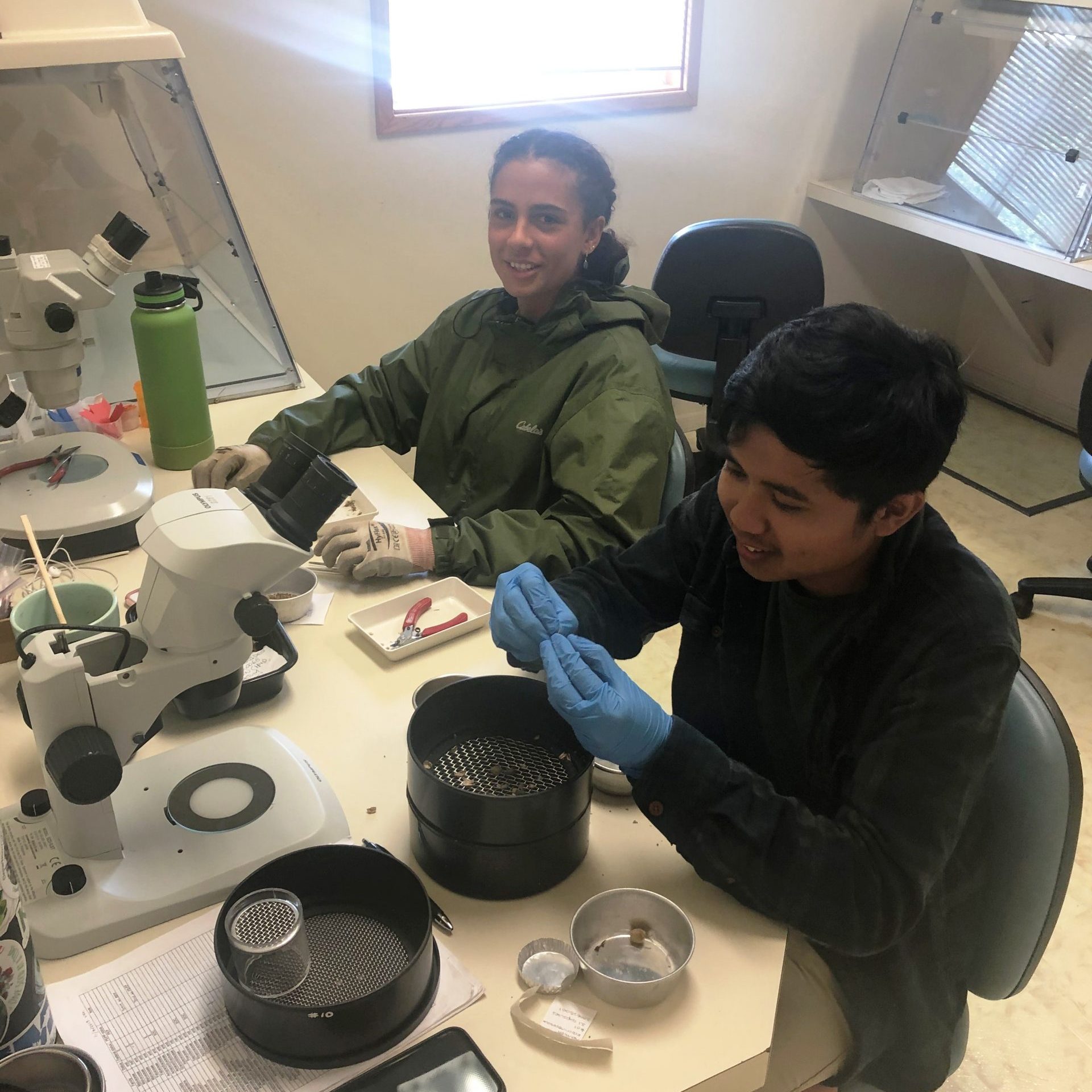

At the Lyon Seed Conservation Lab, we have learned to work through challenging times. Following a staffing change in 2019, we now rely on just one full-time technician and me as the half-time manager, with my joint appointment as an assistant professor at the School of Life Sciences at University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Soon after we started as the new team, the global pandemic hit. Because Hawaiʻi relies a lot on tourism for state’s revenue, there have been various budget cuts and a hiring freeze — definitely not helpful when many species continue to require ex situ conservation efforts. Nevertheless, thanks to many dedicated volunteers, student workers, and interns, we have been able to maintain our operation, processing more than 450 accessions or 200 species with 1.7 million seeds from our dedicated collectors. We have also continued biweekly germination tests. These provide the core of Lyon Seed Conservation Lab’s ongoing seed research, which includes collaborative studies with CPC and Hawaiʻi Seed Bank Partnership group on seed longevity.

Many of our seeds are of highly endangered and rare species and would typically be seen only by designated collectors or those holding a special handling permit. Last year we launched a new project, led by our technician Nate Kingsley, to digitalize microscope photos of our banked seeds. Nate’s expertise, developed at the University of Tennessee Herbarium using a microscope with z-stacking capability, enables us to create more three-dimensional images that are better at capturing fine seed details than our past photos. Lacking an expensive microscope that automatically z-stacks images, we have trained people who work in the lab to manually create these improved images using image-processing software. Ultimately, we hope to make digital images of our seeds available to the public, so that people can appreciate the diversity of rare seeds in Hawaiʻi, learn about their morphology and functions, and use them for research. And all this will be possible without opening up our stored seed packets and compromising their longevity.

This year, I received funding from the O’ahu Army Natural Resources Program (OANRP) to support a new Ph.D. student, Sunyoung Park, in a research project studying causes of low seed viability in the endangered species, na’ena’e (Dubautia herbstobatae), a member of the sunflower family (Asteraceae) or the silversword alliance. Many species in Asteraceae show self-incompatibility (they cannot pollinate themselves), and previous hand-pollination attempts using intra- and inter-population pollen by OANRP staff has resulted in low seed viability. Na’ena’e plants occur on steep cliffs and their seeds are quite difficult to collect. Developing a reliable ex situ conservation method is therefore critical. Thankfully, when viable seeds are available, they store well in conventional seed bank conditions. In the coming year, we will conduct hand-pollination treatments using different founders, assessing pollen germination and pollen tube development.

We would like to be able to identify populations that are not closely related to avoid self-incompatibility issues and maintain genetic diversity. However, considering the small remnant populations of na’ena’e left in the wild, we may not have that option. If inter-population crosses are not successful, we will conduct treatments that have successfully overcome self-incompatibility in various crops. Our intent is to establish a reliable ex situ conservation method for na’ena’e, but many related species face similar reproductive challenges in small remnant populations without sufficient genetic diversity and may benefit from our efforts. Dubautia is endemic to Hawai’i, and nine of the 26 species in this genus are endangered. We hope that insights gained from this project will also help improve ex situ conservation and propagation of many other endangered species in Hawai’i.