Saving Land to Save Plants in a World of Change

For over a hundred years, entities in New England have been working to conserve land in order to conserve nature. While the acreage or quantity has been adding up, the quality of the land—how effective it is at conserving biodiversity—has been unknown. Recently, Michael Piantedosi, Director of Conservation, and the staff at the Native Plant Trust (NPT) realized they were in a good position to examine the quality of the region’s land conservation efforts. The NPT team knows plant diversity, which is the foundation for overall biodiversity. For decades, NPT has gathered information on rare plants across New England and shared it with the appropriate Natural Heritage Program in each of the six states. This work has equipped the states with solid knowledge of their rare plant ranges, status, and threats.

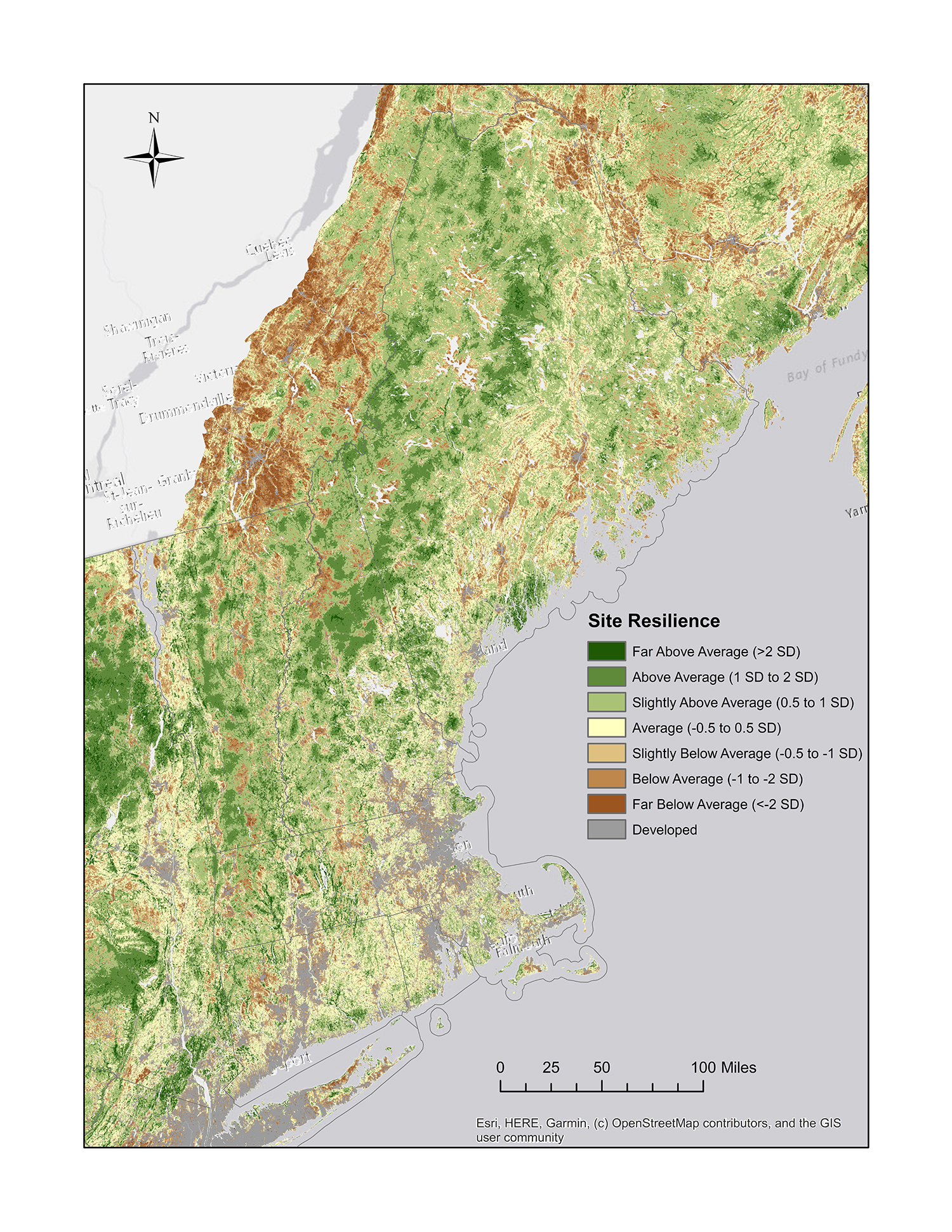

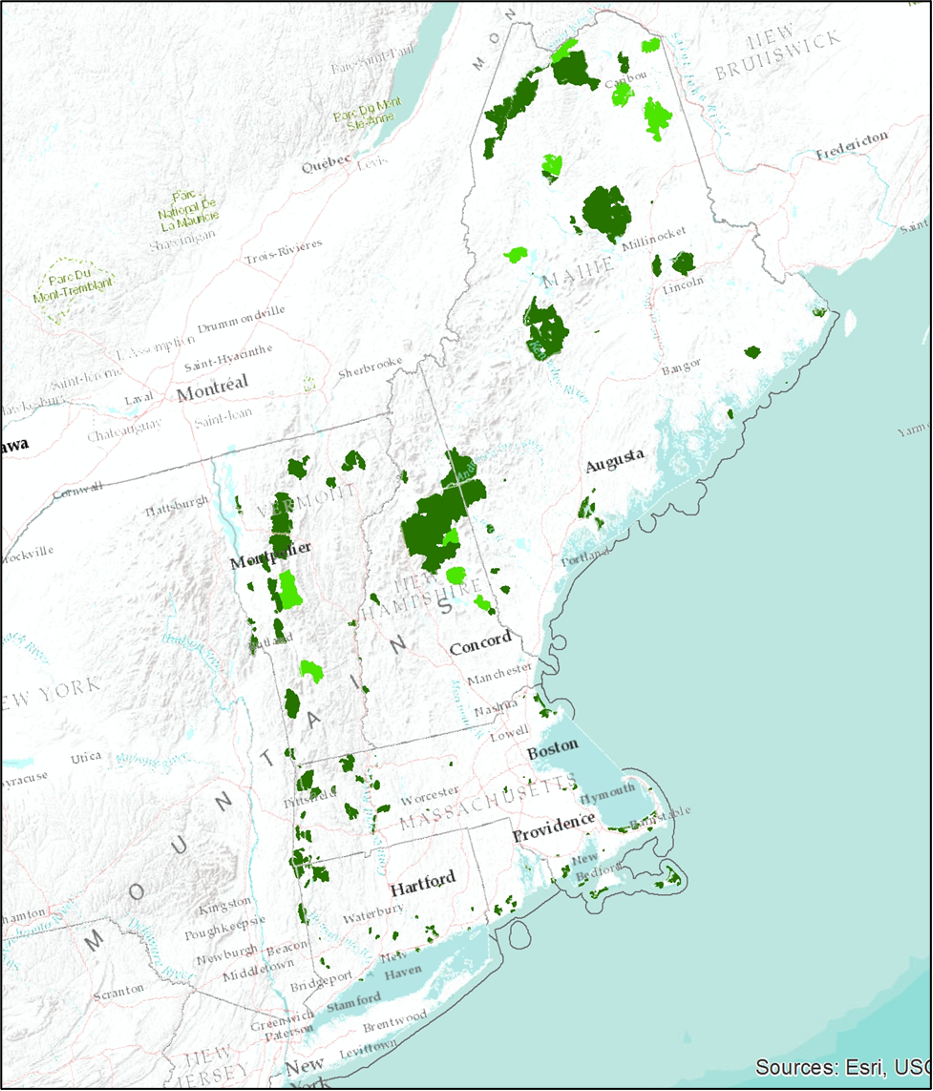

NPT partnered with the Nature Conservancy (TNC) to combine data and expertise, strategically applying spatial data in maps to account for where and how different ecosystems would—and would not—be altered by climate change. Armed with a robust plant dataset, Michael and the NPT team were able to identify Important Plant Areas (IPAs), which are regions with significantly higher populations of rare plants than neighboring areas. Key resources developed by TNC included habitat maps that allowed the team to focus on habitats rather than species, models of habitat climate resiliency (how features in the landscape might buffer species from the impacts of climate change), and data compiled on the conservation status of lands in New England.

Using these data, the team was able to assess the state of biodiversity conservation in New England and compare those results to 2030 goals set for the region (side bar). In the end, the two entities created the “Conserving Plant Diversity in New England” report and accompanying mapping tool. Overlaying various information layers in the mapping tool reveals what percent of each habitat type falls in protected areas, how much of that preserved habitat is also climate resilient, how IPAs are distributed across the habitats, and how the IPAs are protected. This tool can be used by land trusts, public officials, and others to identify lands that would most benefit biodiversity conservation efforts into the future.

After looking at the protected status and climate resiliency of habitat and plant diversity, the report team looked at the percentages of land secured to where New England was doing well and where needed more conserving. National and international guides provided benchmarks for comparison to measure success at reaching specific conservation goals. President Biden’s America the Beautiful Initiative recognizes the Global Deal for Nature’s recommendation to protect 30% of the world’s ecosystems by 2030 while the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC) recommends conserving 75% of the most important areas for plant diversity and protecting 15% of each vegetation type. Tailoring New Englands goals to these larger standards, the team created targets to parallel the GSPC targets with a timeframe of 2030: 1) At least 5-15% of each habitat protected and at least 30% secured against conversion. At least 75% of the securement on climate resilient land, and 2) At least 30% of each climate-resilient area with the highest rare plant diversity (IPA) protected and at least 75% of each IPA secured against conversion across habitats and states.

The results held their share of ups and downs, as well as surprises. One of the ecosystem types, coastal plains, was found to be both susceptible to development and occurring in areas of low climate resiliency, making it particularly vulnerable. Fortunately, a portion of this habitat type is conserved on climate-resilient land. Although forests cover 86% of the landscape, only one of the 10 forest types was found to meet the regional goal of being 15% protected. An additional 2 million acres of climate-resilient forest is needed to meet that goal across all forest types. Michael was encouraged and surprised by the fact that the IPAs were proportionally distributed among habitat types, not just in patchy “specialty” habitats like alpine grasslands or bogs—indicating that efforts to conserve all IPAs would generate great progress in conserving most of the habitat type.!

As the team disbursed and promoted the report, they learned how much people had been looking for such a tool. Land trusts—non-profits that acquire and manage land and conservation easements—want to conserve ecologically important land, and many had been contemplating how to measure this. Now they have that ability. Michael has been busy sharing the report with every land trust in the region, local agencies, and local and national politicians, as well as training others on how to use the mapping tool. The report’s positive reception is a sign of hope for plant diversity as people gear up to take action.

Although NPT does not use land acquisition as a primary tool, the report will guide their actions in other ways. The IPAs identified will be good sites for surveys and inventories to monitor diversity. The tool will also help with selecting rare plants to target for seed banking or other ex situ protections. For instance, for a species with nine out of ten occurrences on land that is climate-vulnerable or at high risk of development, those nine populations would be high-priority seed banking targets. The maps can also help the team plan experiments in assisted migration, by identifying plants that have at-risk populations but suitable habitat nearby on climate-resilient land.

The report team views their product as living document, with an electronic format lending itself to additions and edits. Michael is looking forward to examining the data at a finer scale, taking a look at microhabitats or more precisely defined habitat types. And, of course, the team will examine progress in 2030 to determine how close the six states come to meeting the ambitious goals set in the report.

The strength of Natural Heritage Program plant data across the U.S.–along with TNC’s widespread efforts to conduct conservation land gap analyses and map climate resiliency–will allow the analyses behind the Conserving Plant Diversity in New England report to be recreated in many regions. Learn more about the data used in this report below.

Rare Plants – NPT has worked with partners in its New England Flora Committee to keep rare plant rankings updated, most recently in a 2012 update to Flora Conservanda. Location data on the occurrences (or populations) of these rare plants is held in the Natural Heritage programs of each state.

Conserved Land – This project identified four levels of conservation status: 1) Protected for nature and natural processes (e.g., natural reserves, designated wilderness areas); 2) Secured for nature with management (e.g., National Parks); 3) Secured for multiple use, some of which may cause disturbance (e.g., national forests with logging or grazing lots); and 4) unsecured. The data came from a conservation land gap analysis in TNC’s Secured Land dataset.

Habitats – The Northeast Terrestrial Habitat Map, which served as the key data source for habitats/ecosystems, delineates 43 unique habitat types across New England. The habitats are comparable to the NatureServe ecological system classification.

Climate Resilience – TNC devised an approach for assessing based on enduring geophysical characteristics of the land. They score every pixel of mapping images to account for diversity of microclimates and connectedness between patches of an ecosystem and key landscape features like water sources. This system allows TNC to identify areas of high and low resilience to ecosystem changes resulting from a changing climate.

Development Threats – To estimate the threat of conversion from natural to developed lands, the report team used a Land Transformation Model that was developed by the Human-Environment Modeling and Analysis Laboratory at Purdue University to determine land likely to be developed by 2050.