Recovering Bradshaw’s Desert Parsley

Bradshaw’s desert parsley (Lomatium bradshawii) is a lovely member of the carrot family that may soon find itself coming off the endangered species list (or possibly downlisted to threatened). During much of the 1900s, this species was apparently thought to be extinct, until a University of Oregon graduate student rediscovered it. Or perhaps it was only considered rare and hard to find, but not really extinct. It is actually quite difficult to know whether a plant population is extirpated (no individuals remaining in a certain geographical location) or a species is extinct. But what is clear today is that Bradshaw’s desert parsley has a larger number of populations and more robust populations than it did when it was first listed in the 1980s – and the Institute for Applied Ecology (IAE) has played a large part in that success.

Found only in Oregon and Washington, Bradshaw’s desert parsley has lost habitat to farmland and other development. The remaining wild habitat is being impacted by changes in land management – specifically, the decline of fire in the ecosystem. However, when Tom Kaye, executive director at IAE, began his graduate work on the species, there was only the slightest indication that fire might be important. His work documented the effects of fire as a management strategy at a handful of sites, with the data showing an increase in population size. The research suggests that populations can tolerate fire every year, and they may need fire at least every three years for population growth. A lack of fire at a site eventually leads to a population’s decline.

Grazing can potentially play a similar role in the management of the the parsley populations. Grazing, like fire, removes the thatch of plant material that can build up in the wet grassland systems the plant calls home. Thatch affects various living and non-living aspects of the habitat, including negative impacts by voles. These stout rodents seem to have a preference for the rare plant, and they have been seen piling cut pieces of the Bradshaw’s desert parsley next to their burrows. Reduction of thatch causes the voles to lose cover from predators. Fire or grazing may therefore make the Bradshaw’s desert parsley habitat less attractive and push voles to relocate to other sites, where their voracious appetites do less harm.

-

Early research into restoration practices determined that seeding into bare ground was a cost effective solution for this perennial species. -

Rare plants are important components of ecosystems – here Bradshaw’s lomatium supports a swallowtail caterpillar. The plant blooms early and is actually an important source of nectar for pollinators early in the season when little else is in bloom. -

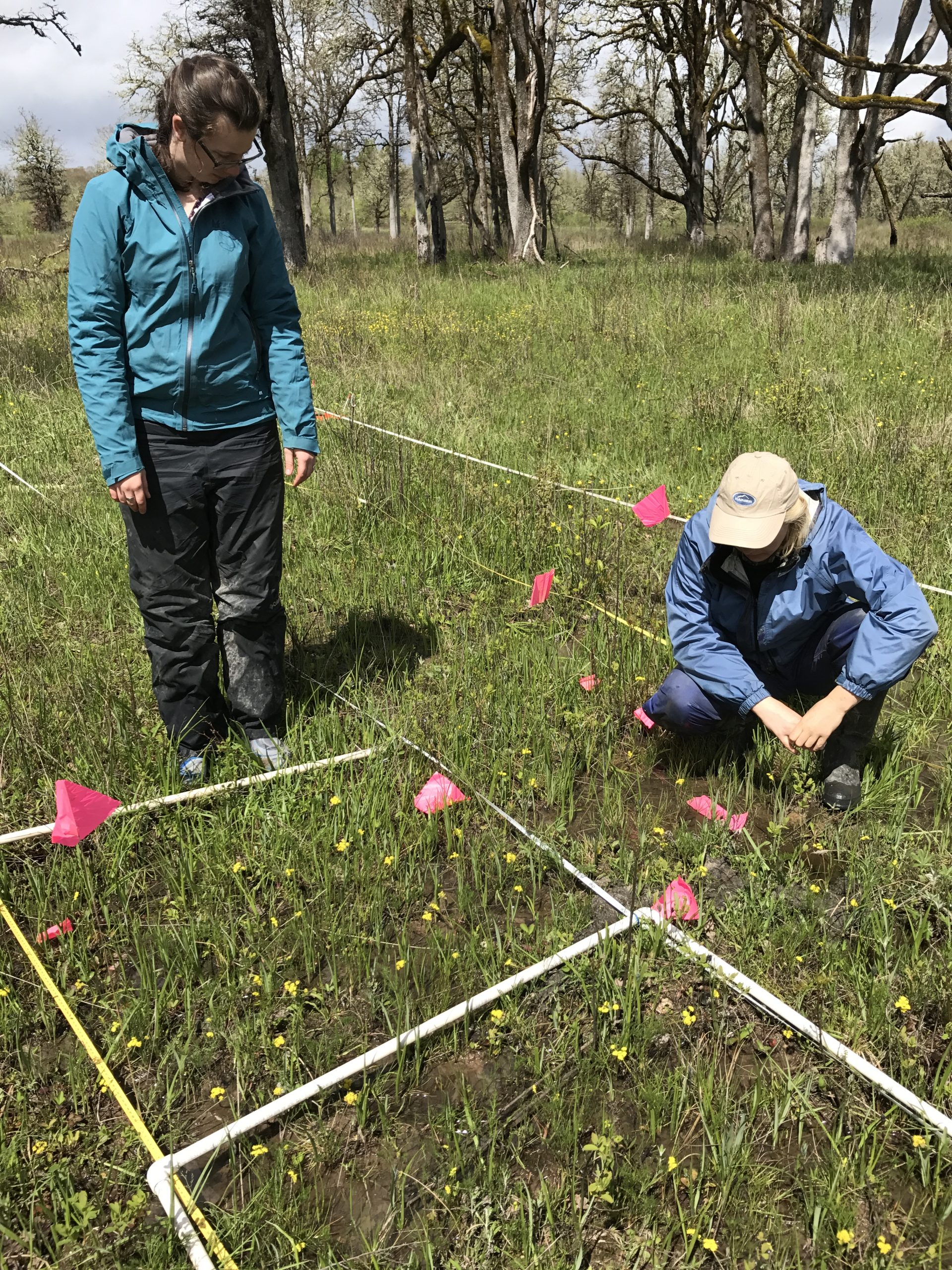

As part of range-wide survey, IAE staff monitored populations of Bradshaw’s desert parsley across Washington and Oregon.

At IAE, Tom focused on applied research for new population establishment. Using seed collected from the remaining wild populations, the IAE team produced small plants (“plugs”) and vast amount of seeds that they used to restore different locations. Plugs are more expensive than seed to grow out, install, and care for, but for many species they have higher survival rates. With parsley, however, the team discovered that the seed and plugs worked equally well. Applying the large seeds to bare soil (with thatch removed by burning or grazing) resulted in an impressive 30-70% rate of germination and plant development.

This technique was used by IAE at the William L. Finley National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) and other locations and was also put into use by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Many land managers have been great partners in the efforts to increase Bradshaw’s desert parsley across its native states. The Bureau of Land Management, Army Corps of Engineers, Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, local governments, and private land trusts have all supported restoration at some level. However, not all the reintroduction projects were being tracked long-term. Although it was clear that the situation was improving in many places, the big picture for the species was still blurry.

To fill this important information gap, IAE conducted a range-wide survey of Bradshaw’s desert parsley a few years ago. The survey provided updates on reintroductions that were no longer being monitored. One of the places revisited was a site on William L. Finley NWR that had been seeded but not checked on in years. Tom and crew expected to find a few hundred individuals in the area of the seeding. As they walked up to a happy patch of yellow flowers, they knew there were many more. But it wasn’t until they were down on their hands and knees in the survey plots counting all the little seedlings that they realized the population was around 10,000!

Even more valuable than an update on specific populations, the survey provided a snapshot of the overall status of the species. The number of populations reported in the survey supported the delisting requirements. However, Tom warns that a population “can decline at the drop of a hat” with management changes, and he recommends continuing to monitor the species at this scale to obtain more than a one-time snapshot.

Regardless of the endangered species status, management of Bradshaw’s desert parsley will be a continuing challenge. Balancing the disturbance needs of the parsley with the habitat needs of other species to promote diversity can be tricky. Although fire seems to be the best way to provide disturbance, it isn’t always logistically feasible. Grazing may help on “working” lands, such as ranchlands and farms, but it can be difficult to manage safely and consistently. Though the species is doing well for now, a great deal remains to be learned to help ensure its safe future.

All photos courtesy of Institute for Applied Ecology.