Reaping what we’ve sown: Using long-term seed collections for novel seed conservation research

Working with the CPC network over the past five years has opened my eyes to many conservation truths—none more important than seed conservation. The diversity of methods we used to process and store seeds in long-term collections mirrors their remarkable variation in nature, ranging from the dust-like seeds of orchids to five-pound coconuts. “Seeds are not rocks,” says Dr. Chris Walters. Because seeds are alive, they are also dying. The use or replacement of priceless, aging seed collections of rare plants before their often unknown “expiration date” is an urgent task for seed banks. Without an exit strategy, seeds we have so carefully collected and curated do not hold conservation value –they are simply fruit rotting in a vault.

Enter the dedicated conservation officers in the CPC network, who have preserved thousands of rare plant seed collections in frozen storage over the past 40 years. Thanks to their efforts, we are well poised to improve the monitoring of seeds in storage and determine when they might need an exit strategy. Happily, we are now ready to take the next step forward, powered by a three-year, $500,000 National Leadership Grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services, received in August 2020.

The grant funds research to evaluate RNA integrity as a proxy for seed aging in wild rare plant species. This concept arose on a trip I took with CPC’s CEO Joyce Maschinski to visit Chris Walters and her lab protégé, Lisa Hill, at the USDA-ARS National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation (NLGRP) in Fort Collins, Colorado. The mission was two-pronged: to capture Chris and Lisa on video performing their state-of-the-art seed conservation methods (see here and here), and to plan a proposal for rare plant germination research in the CPC network.

During the visit, Chris described her team’s recent work on RNA integrity in crop species to us. Unlike germination tests, which can only detect seed aging after seeds are already dying, RNA integrity declines linearly with the age of seeds. Chris explained that a calculated RNA integrity number (RIN) can provide information about seed age before seeds die, allowing seed curators to grow out or re-collect seed from rare plant populations before their “expiration date.”

To use RNA integrity as a measure of seed longevity, we will first need to evaluate its efficacy in wild rare plant species. This can be done by comparing RNA integrity and germination success between newly collected seeds and seeds aged 20 years or more in frozen storage. To acquire the test material, we would need our Participating Institutions (PIs) to review populations of seeds currently held in frozen collections and allow us to use a small quantity of original frozen seed for research. However, we weren’t sure that we could get the Participating Institutions on board. Would the conservation officers in our network view re-collecting seeds from populations already represented as a worthwhile activity? After all, so many populations—and entire species—have never been collected at all and need their attention.

-

Berberis nevinii is among the species nominated by California Botanic Garden for seed longevity analysis. Photo by Bart O'Brien. -

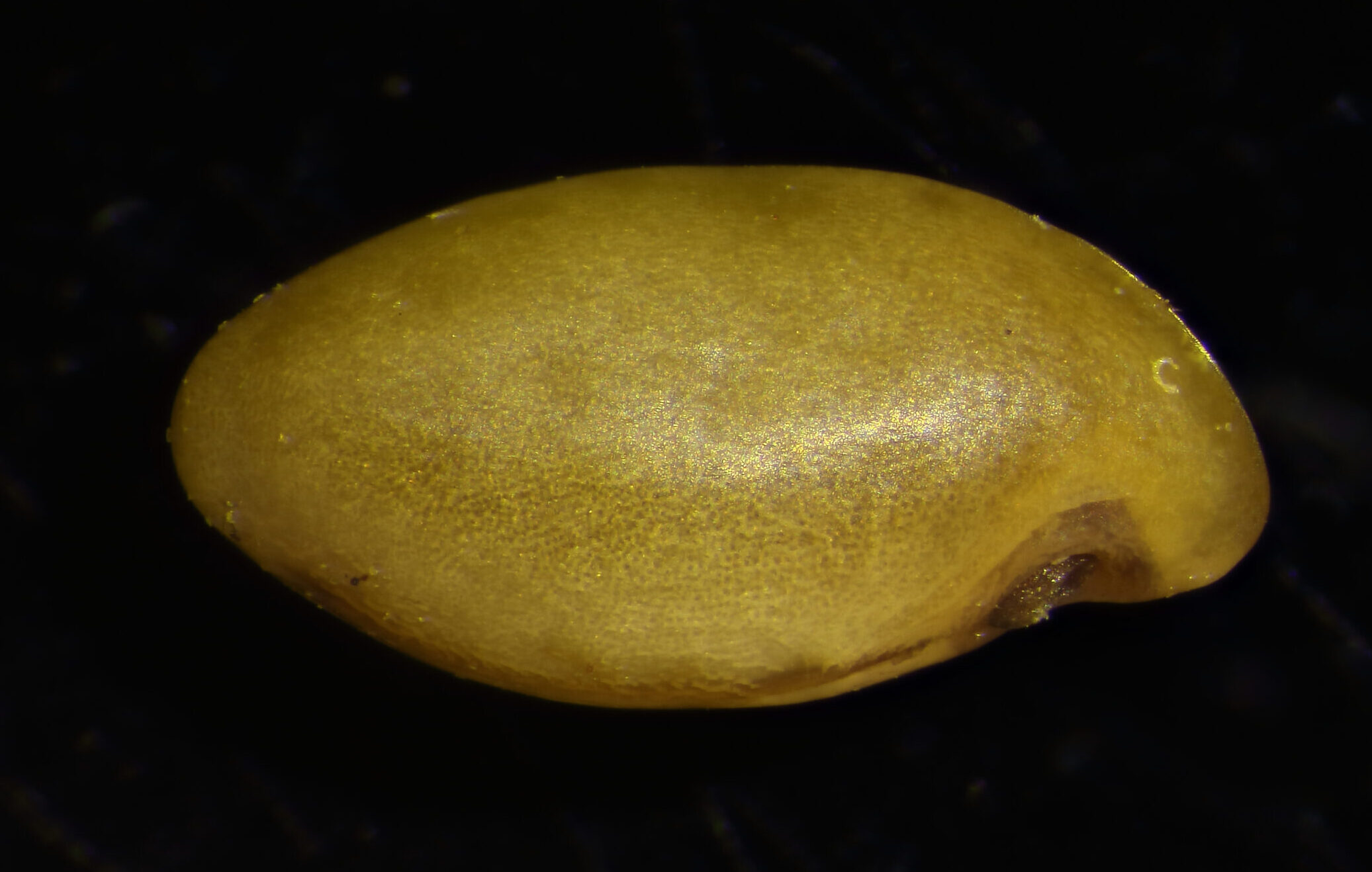

Missouri Botanic Garden will recollect five species for CPC's seed longevity study includes Astragalus bibullatus. Photo by Matthew Albrecht. -

The Institute for Applied Ecology will collect Bradshaw's lomatium from the same population originally collected by Rae Selling Berry Plant ConservationP Program in 1988. The synergy between collecting programs like IAE and long term seed banks like Rae Selling Berry is key to this project. Photo by: Tom Kaye

But the positive response from the CPC network was overwhelming! We received letters of support for the proposal from 15 participating institutions, followed by nominations of over 350 potential plant species from 20 PIs after the grant was funded. Even more impressive than the volume of nominations was the enthusiasm of our network to use the seed collections in their care to further the state of conservation research. I think we all appreciate the opportunity to harvest the fruits of our –or rather our forebears’ -labor.

Now the work begins. This spring, Emma Dorr, a laboratory associate at NLGRP, will conduct RNA assays on common plant species related to the rare species planned for this study. She will determine the feasibility of RNA integrity analysis for a variety of taxonomic groups –which is in question for certain families, most notably grasses. This summer and fall, our PIs will begin making field collections for the 100 rare plant species selected for the study. Our hope is that participating groups will have the opportunity to visit the facilities at NLGRP, see Emma in action processing their samples, and potentially learn how to apply these methods in their own lab.

Many questions remain, and we cannot wait to learn more about these precious—and very much alive—seed collections.