Powerful New Tools to Prioritize California Rare Plant Conservation

California is well known as a global biodiversity hotspot, spanning several major bioregions. While a majority of the state sits within the California Floristic Province – one of five Mediterranean climate regions of the world – California also spans portions of the Sonoran, Mojave, and Great Basin Deserts. It’s no wonder that the California flora is so striking for its diversity and richness, with over 6,600 unique native plant taxa! More than one-third of this diverse flora is endemic to the state (occurring nowhere else), and over one-third is also considered rare or endangered. Evaluating and ranking the rarity of these native plants enables us to focus conservation resources where they are needed — and for more than 55 years, the California Native Plant Society’s Rare Plant Program has done just that.

To track California’s rare plants, the Rare Plant Program developed what is now called the CNPS Rare Plant Inventory (RPI). The RPI includes rarity ranks, threats, location information, and habitat data. It began as a collection of index cards, which developed into a series of published print manuals and now exists as a publicly accessible online database. Modernization of this database over time has been crucial for maintaining and continuously updating population records, ever-changing taxonomy, the latest research, and new threats to California’s rare plants. “The RPI is such a critical conservation tool, helping identify plant species that should become listed under the Endangered Species Act, or preventing them from becoming extinct by identifying at-risk species and prioritizing conservation actions,” said Aaron Sims, Rare Plant Program Director at the California Native Plant Society. CNPS collaborates closely with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s California Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB), which maintains its own database (RareFind) of detailed location information for all the plants included in the RPI.

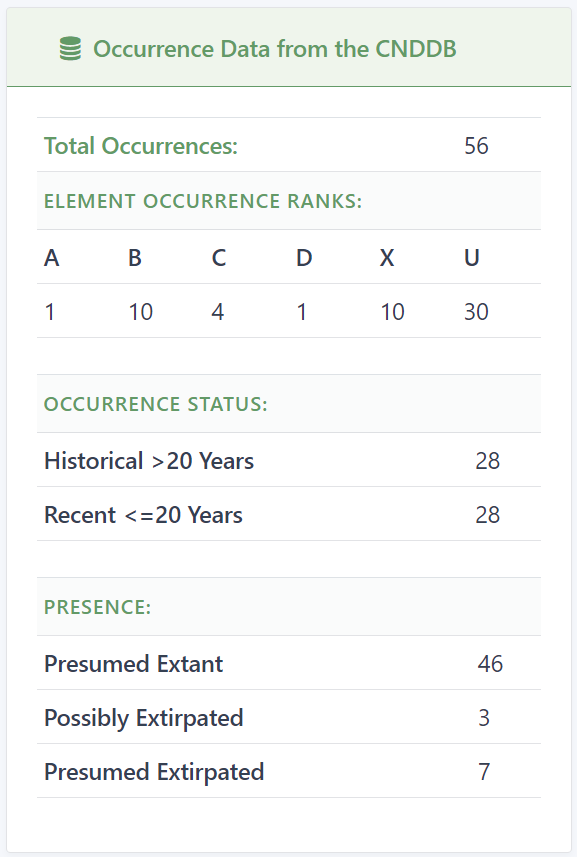

Although the CNDDB and CNPS teams share data, these databases are used differently. The CNPS RPI is open access and obscures location data to the level of 7.5-minute quadrangles (an area of roughly 50-60 square miles) to protect the rare plants from poachers. Within the inventory, each plant has a page that provides a snapshot of important information, such as scientific name, common name, rarity rankings, distribution, habitat, and threats. Many pages feature plant photos and links to more detailed taxonomic or natural history information. Simple and advanced search functions are available. Users – including federal agency partners, academics, conservationists, and the general public – can search the inventory to find out what rare plants occur in a particular quad or geographic area, or for plants that are exposed to particular types of threats (such as development, mining, or poaching). The pages also have information on how many of the plant occurrences are recent (seen within the past 20 years) or historical (not seen in the past 20 years). Rare plant populations that have not been seen and documented for 20 years or more are prioritized for field surveys to determine if the population is stable and whether it is facing new or increased threats.

Recent advancements in functionality of the RPI include automated filtering tools that allow professionals to acquire a list of priority rare plant species quickly and easily. This filtering function creates data output that automatically identifies:

- Species with occurrences that are 90-100% historical

- Species that have only One Known Occurrence (OKO) in the entire world

- Species that might need to have their conservation ranking changed, based on number of occurrences and documented threats

With such a large database and the vast geographic area of California, this functionality in the RPI is an essential tool to help professionals identify and update the highest conservation priorities – in other words, where our limited time and conservation dollars are most needed!

-

Display of newly available threat data in the RPI for Trifolium hydrophilum, indicating nearly half of its occurrences are threatened (46%) and that development is the largest documented threat to this species. Courtesy of the California Native Plant Society. -

Trifolium hydrophilum – southern-most population which had a banner year after several very bad years which led to concern of local extirpation; population data was updated and it was seed banked this year. Photo credit: Kristen Nelson. -

Occurrence statistics for Trifolium hydrophilum. Here we can see that half of its occurrences are historical (over 20 years old), with 10 occurrences being possibly or presumed extirpated. Courtesy of the California Native Plant Society.

When plans were being developed for the 2023 field season, data from the RPI enabled researchers to identify the Santa Ynez groundstar (Ancistrocarphus keilii) as a key conservation priority. Two reasons stood out: this species is known from only a single, small occurrence (one patch of ground in the entire world); and that lone occurrence had not been documented in almost 30 years. Without field work and data collection to update the Santa Ynez groundstar’s record for this population, we were lacking critical information about its status and potential conservation needs.

A successful expedition to find and document the Santa Ynez groundstar soon followed. A collaborative group of botanists from Santa Barbara Botanic Garden and CNPS collected new voucher specimens, completed conservation seed banking, acquired the first-ever photos of this plant in living condition, and collected detailed data about the status of the population and its habitat. News of the expedition and its “rediscovery” of this diminutive species made headlines! “Building off the excitement of a superbloom year in California, and being able to share striking photos of this plant that hadn’t been seen in decades, helped this story go viral and drew much-need attention to the importance of plant conservation,” shared Sims.

This conservation success story was made possible with the CNPS Rare Plant Inventory, paving the way for even more of California’s vulnerable flora to be identified, prioritized, and preserved for future generations.

-

Phacelia exilis in the Santa Clara River (Utom) watershed. Photo credit: Jordan Collins. -

Jordan Collins collecting population and habitat data for a historic population of Caulanthus californicus, which CNPS updated this year. Photo credit: Kristen Nelson. -

Monolopia congdonii in Carrizo Plain National Monument. Photo credit: Kristen Nelson.