On the Run: Recovering a Fugitive Species

On the sandy coastal dunes of Atlantic barrier island beaches, just beyond the high tide line, lives the Seabeach Amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus), a federally threatened annual herb that is facing significant decline in its natural habitat. Once common along much of the eastern seaboard, from South Carolina all the way up to Massachusetts, this rare plant species is now extirpated from the states of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, and needs significant conservation intervention to survive and thrive.

“This is a plant that has been of great interest to us for a long time, especially with its precipitously declining populations all throughout its range,” shared Dr. Johnny Randall, Director of Conservation at the North Carolina Botanical Garden (NCBG). They have been working to conserve Seabeach Amaranth since making their first seed collections of the species in the 1980s. “It’s such an interesting plant, being one that is on the frontier – it’s truly on the edge of a habitat that is really vulnerable,” continued Randall. The Seabeach Amaranth’s precarious habitat is created by tides, wind, and storms. The species is intolerant to saltwater exposure, so individuals and habitat are often lost after storm surges and overwash events. It is also threatened by human development and recreation, in addition to sea level rise and beach stabilization efforts such as jetties and dune fencing. Often dubbed a “fugitive species,” Seabeach Amaranth is always on the run from threats and competition to seek out suitable habitat to call home.

In 2015, NCBG began a partnership with the US Fish and Wildlife Service to reintroduce the Seabeach Amaranth in six wildlife refuges and some private lands within its native range along the Atlantic coast. They expanded this effort in 2018 by partnering with the National Park Service on reintroductions on Cape Lookout National Seashore, North Carolina. Central to these reintroduction efforts is seed increase efforts, or bulking. “We chose to work with seeds because the wide geographical range we were working in – from South Carolina up to Cape Cod, Massachusetts – made transporting mature plants unfeasible, but first we needed to get sufficient seed stock to do it,” said Michael Kunz, Associate Director of Conservation at NCBG. Since this species was struggling in the wild, their team turned to accessions stored in their seed bank (39 collections from 23 populations throughout the species range) and conducted seed increase to generate enough seed for the reintroductions.

In a few cases, the NCBG team needed to make fresh seed collections. “Since this is a particularly vulnerable annual species, we often don’t collect even the full ten percent in order to not harm the wild populations, which is fairly easy to do given the species’ long flowering period and heavy seed production,” continued Kunz. “This allows us to collect an ample supply to start ex situ populations for seed increase, even from small wild populations.”

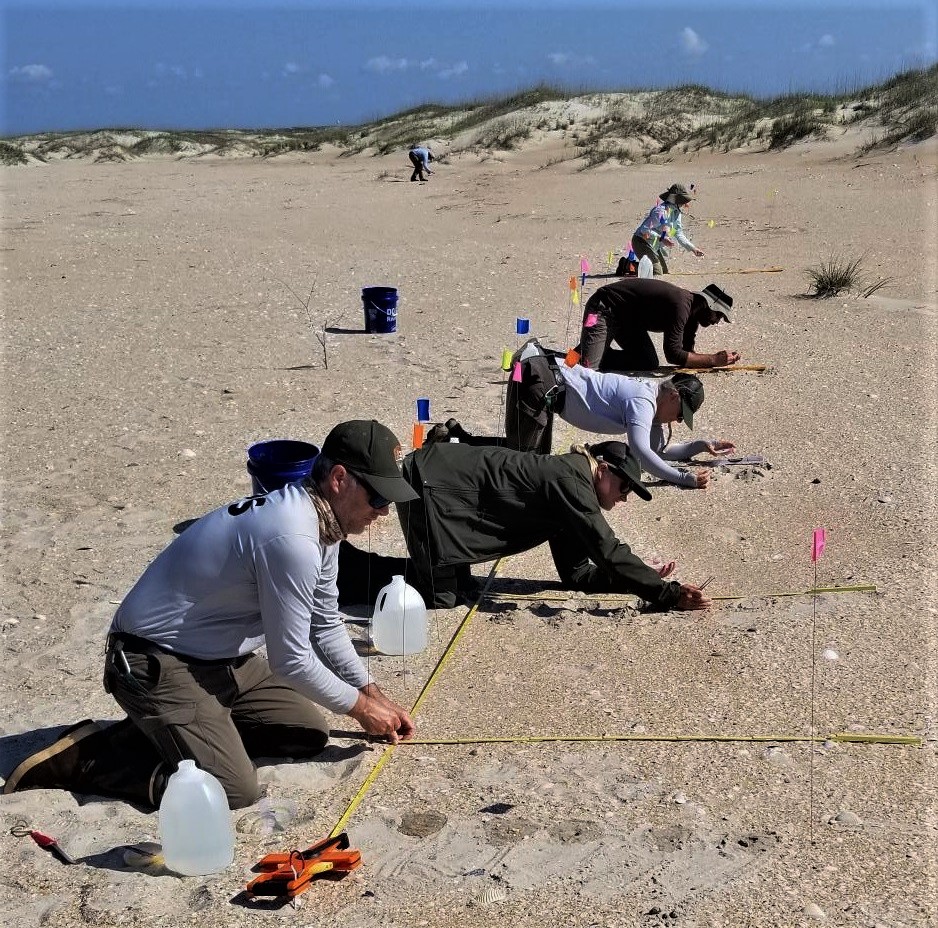

Once seeds are planted back into the wild, various partners help monitor plots where seeds were planted. The long-term goal is to continue establishing plants so seeds are continually being put out in the environment. “Since it is a fugitive annual, populations will fluctuate naturally, so not finding plants in the wild after a couple of years is not a failure, but a bump in the road to where this plant is going,” said Kunz. “Hopefully, by continuing to get plants out in the environment, we’re adding to this long-term natural seed bank – with the hope that when conditions are right, these plants can germinate and show back up on their own.” The team at NCBG also have an eye toward optimizing efficiency and effectiveness by finding ways to use the least number of seeds or plants while maintaining a high success rate.

Conservation initiatives like this require long-term monitoring and management, but also provide opportunities to further research and better understand this species. One example is geographic-based genetic variation.

After beginning seed increase efforts in their greenhouse, the NCBG team found distinct phenological differences among plants along the geographic gradient, indicating genetic diversity – which probably accounts for variation seen among plant sizes, flowering times, and other traits from different sites. “This is one of the reasons we’ve stepped up our efforts to do seed increase, so we have enough seeds from as many representative populations throughout the range as we can, which helps avoid interbreeding – and we do have most of the species’ range captured in our seed bank,” said Kunz. Additionally, Seabeach Amaranth has been selected as a subject species for CPC’s IMLS-funded Seed Longevity Study, which will better our understanding of seed viability in long-term seed bank storage to ensure better stewardship of these precious natural resources.

With these ongoing conservation actions, North Carolina Botanical Garden hopes to ensure the Seabeach Amaranth’s recovery so that this fugitive species is no longer on the run, and can settle in its natural coastal habitat long into the future.

Learn more about NCBG’s conservation work with Seabeach Amaranth by viewing Michael Kunz’s 2022 CPC National Meeting presentation, “Bringing Back a Fugitive,” on the Rare Plant Academy.

Further reading: Stalking the Wild Amaranth: Gardening in the Age of Extinction.