Save Plants: July 2020 Newsletter

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

July 2020 Newsletter

In the early days of CPC, 36 years ago, learning about the rare plant species in a region took quite a bit of effort – from gathering paper copies of recovery plans mailed from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to perusing five-inch thick volumes of three-ring binders with information from State Natural Heritage Programs. Copious notes documenting conversations with regional rare plant experts also helped us assess whether a plant population was stable, declining, or growing, and whether a particular species should be listed as endangered or threatened. CPC’s archives are filled with pages and pages of documents about rare plant species. Today these resources are available through an easy search on the web. A key digital resource for determining the conservation status of a species can be found by visiting the Nature Serve website.

In this issue, we honor the State Natural Heritage Programs and the NatureServe Network. When all of us share our data, we generate great value that helps us accomplish efficient targeted plant conservation.

We wish you and your families continued good health and safety.

Joyce Maschinski

CPC President & CEODigital Bean Counting: Facilitating a Statewide Seed Collection Initiative through Data Sharing

Have you ever received a letter or text that wasn’t intended for you? A few years ago, I received a Christmas card with a picture of a pug photoshopped on top of an elephant with the hand-written message “Merry Christmas, Hobgoblins. Love, Linda & Hadley.” Reading this immediately turned me into a private eye. Was Linda the woman next to the elephant? Is Hadley the dog, or the other way around? Did the woman see this elephant on a safari? Is this Hobgoblin one of my neighbors?

I find compiling other people’s data to be a fun mystery not unlike receiving a wayward holiday card. As a biodiversity data scientist (a term I think I made up), I’m often presented with spreadsheets of plant records with no contextual knowledge of the people–who collected them–or the species or populations the data represent. Because these records often predate the current data contributors, it’s an art speculating about the meaning of some of the data.

Mostly I have boring questions, such as “What are the units on this column labeled Plant Height?” But sometimes I stumble upon anecdotes in the locality notes that bring the collection record to life. One that I particularly enjoy is in UC Berkeley’s living accession of the Catalina Cherry (Prunus ilicifolia subsp. lyonii) originally collected on the Channel Islands, which notes the collectors’ urgent need to “abandon toyon seedlings and retreat from pigs” at one critical point.

This challenge of compiling data is not just a nerdy academic exercise—it has real conservation importance. In 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic closed the economy and drained state budgets, the California legislature approved a $3 million budget line item to collect seed from all remaining rare plant species in California not currently represented in the California Plant Rescue seed banking network. The California Plant Rescue Database—which CPC has operated and maintained since 2017—has been instrumental in determining the targets and facilitating collections planning. This database of seed and living collections from six of California’s largest botanic gardens (California Botanic Garden, San Diego Zoo Global, UC Berkeley, UC Santa Cruz, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, and Regional Parks Botanic Garden) contains 18,067 records of 2,547 species spanning collection dates from 1938 to 2019.

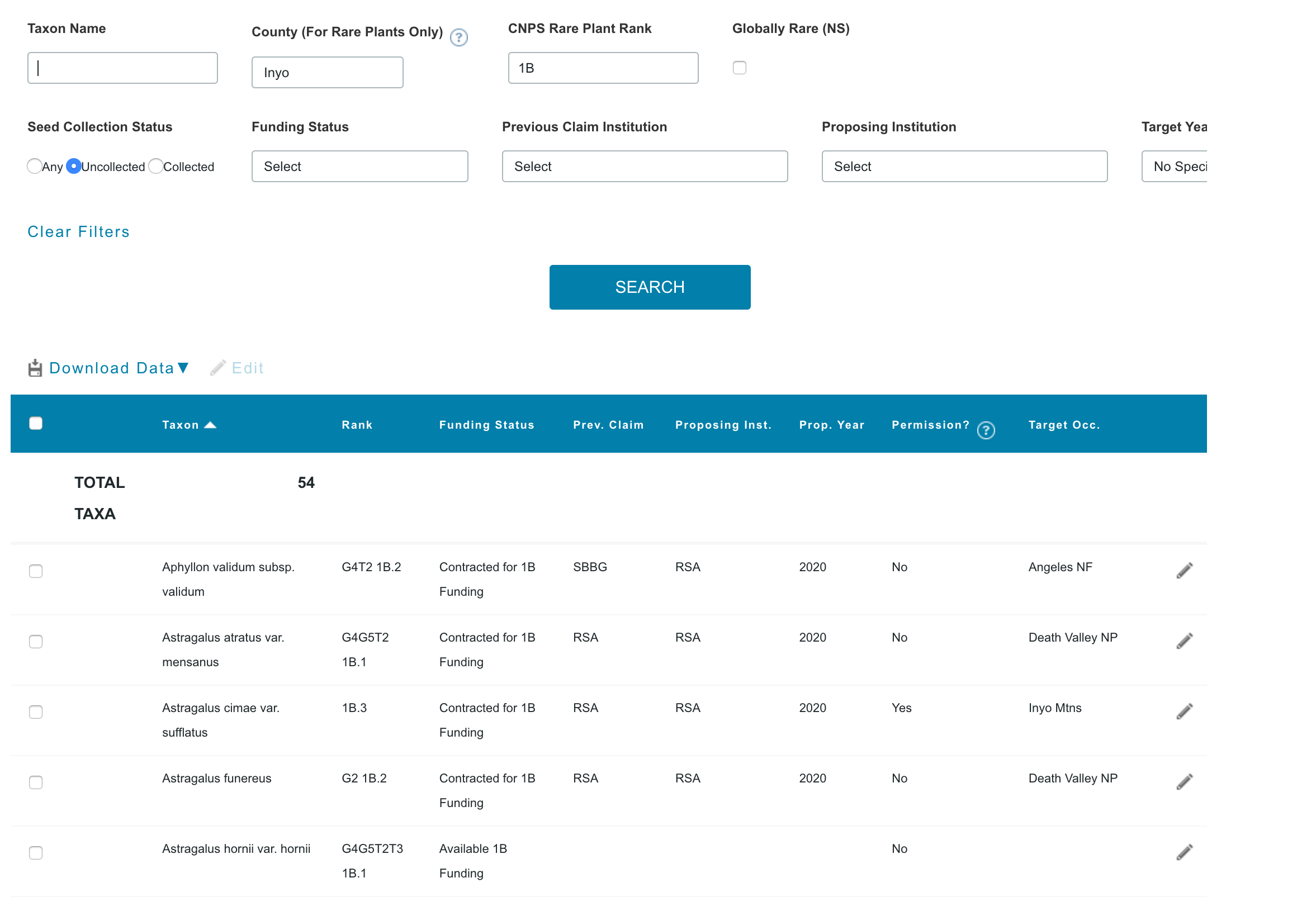

While the public can view a limited set of the California Plant Rescue Database, its focal users are California’s seed collectors, who have generously shared data with one another in the name of maximizing conservation effectiveness. Our collectors can use the members’ database to find the size, age, location, conservation status, and processing type of seed collections in California. In addition, this database offers a number of tools for collecting, including a targeting tool that facilitates communicating collection plans and a running total of rare species in seed collection. The goal of the California Plant Rescue Network is to secure 1,166 species ranked as 1B, plants that are rare or threatened in California by the California Native Plant Society and the State in seed collection by the year 2025. We have only 567 species to go!

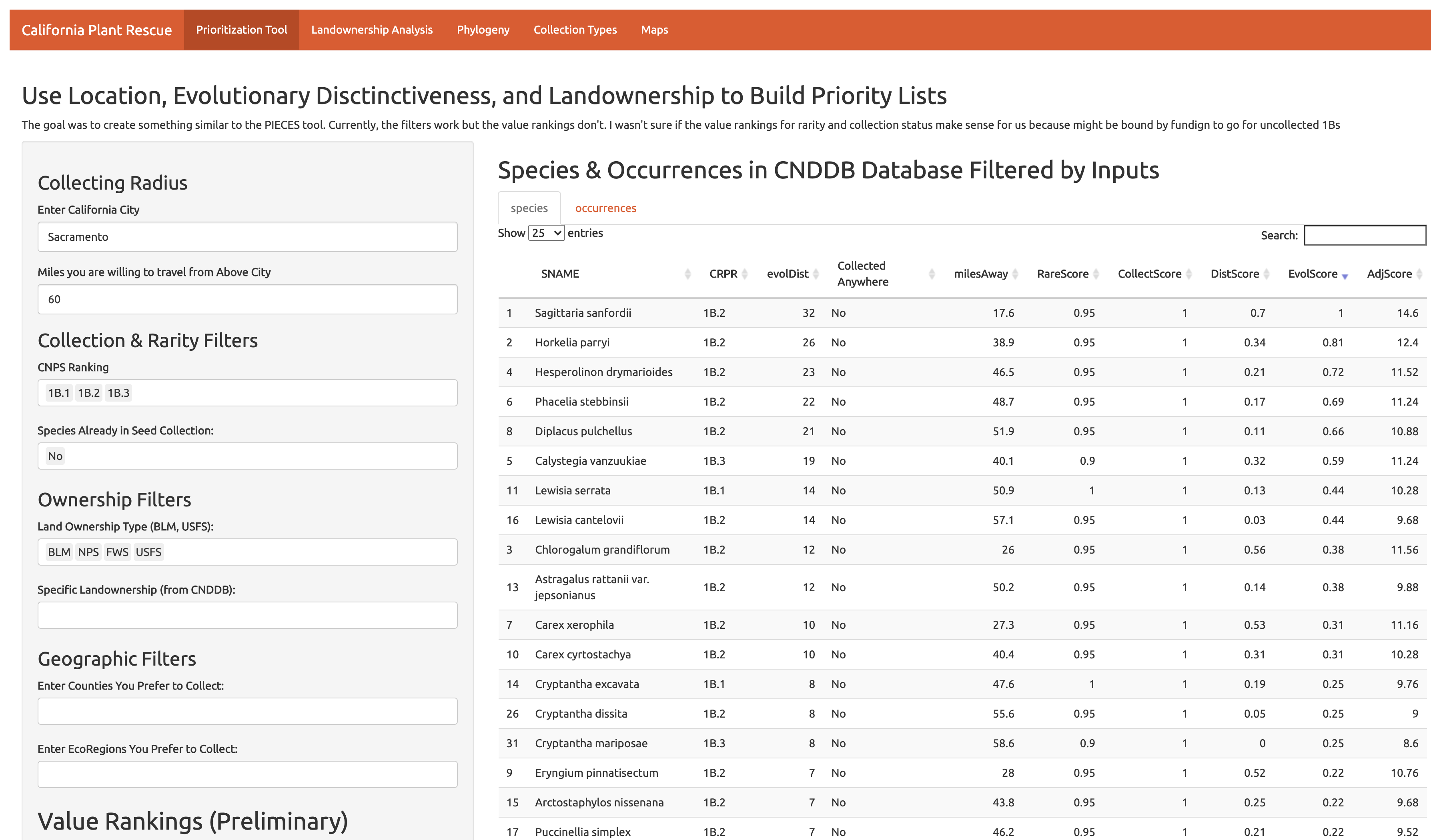

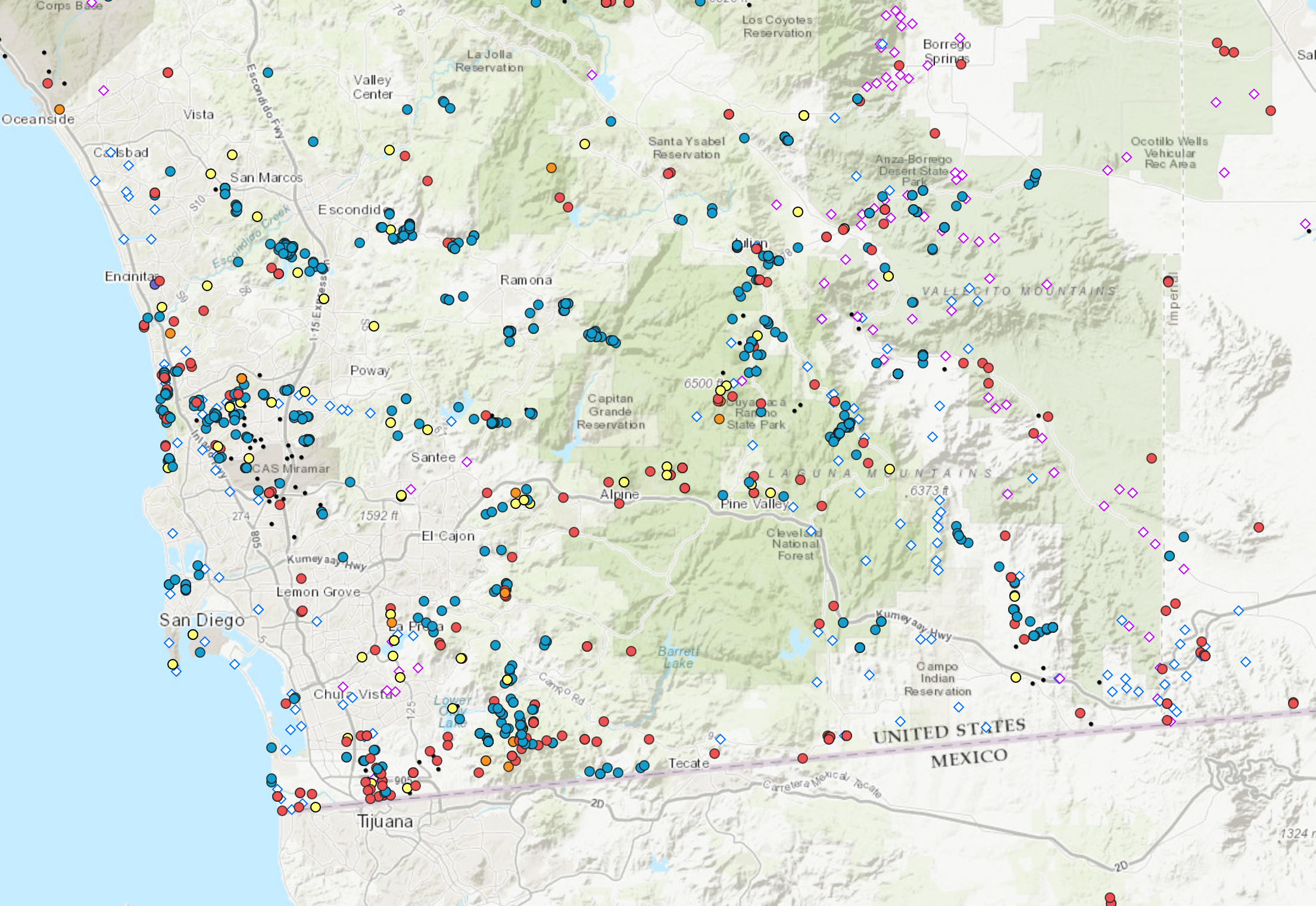

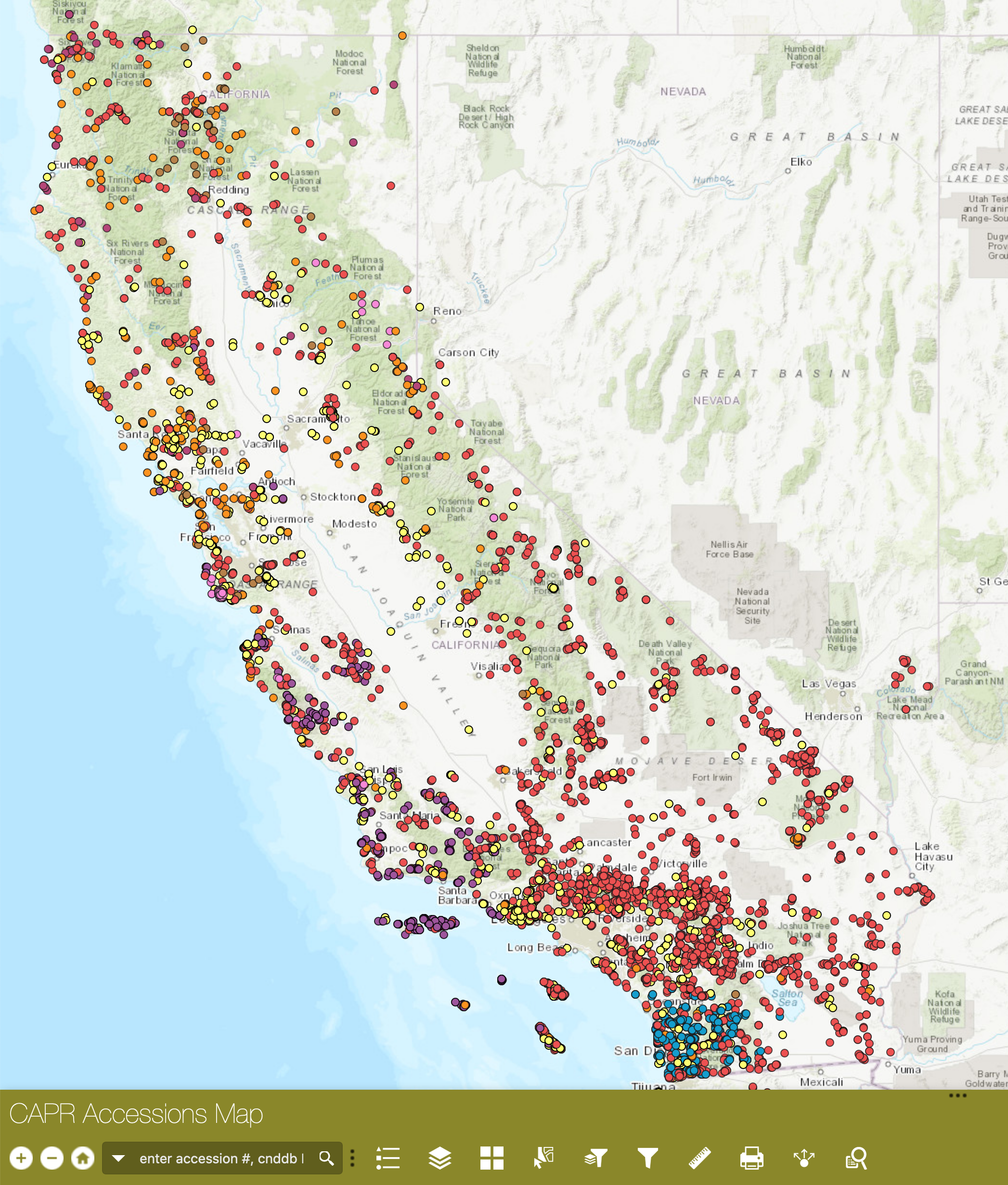

We also have created a spatial mapping tool that integrates the rare plant occurrence from the California Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB) with our combined seed collections. This enables collectors to locate both past collections and candidates for future collections.

Finally, we created a tool that allows collectors to search for uncollected species on the land management units in which they have permission to collect, within a specified range of their home institution or other landmark.

At the CPC National Office, one of our near-term goals is to consolidate these resources into a more unified platform and extend this software and collecting paradigm to other states and regions. We believe that the collaborative spirit of the CPC network lends itself exceptionally well to the divide-and-conquer mentality that will allow us to achieve our ultimate goal: to safeguard all of the imperiled plant species in the United States. Thank you to all of our partners, who have allowed me the opportunity to compile your data so that we can build a more collaborative and successful collecting community.

Tying together population and collection data, both with spatial data, CPC was able to develop a priority targeting tool for CaPR. With this tool, collectors can quickly find out what other species might be in an area they are already seeking to collect in and have permits for, or otherwise use to develop a target list.

By bringing together all CaPR partner data, we are able to track progress towards our goal, identify species that fit our funding source criteria, and much more. In this search we see that the county of Inyo has populations of 54 rare and threatened species, and that CaPR partners are targeting some of these species for collection.

Your State Rare Plant Data Centers – The Natural Heritage Network

Our natural heritage is the sum total of our biodiversity, ecosystems, and geological structures. More and more people are thinking about what this means to us. What have we inherited? What will we pass on to others? It’s essential that we know what we have in order to care for it and be able to pass it on. This knowledge is a key role of the Natural Heritage Programs that constitute the NatureServe Network, a group of primarily state-based public and private entities that gather, inventory, assess, and manage data on rare and threatened species and ecosystems in each state.

There are currently about 100 Natural Heritage Programs now, covering all 50 states, the Navajo Nation, Canada, and several Latin American and Caribbean countries. Many still carry the Natural Heritage Program name (e.g., the North Carolina Heritage Program), while others have been folded into government or university programs with different names and, in some cases, expanded roles (e.g., the Oregon Biodiversity Information Center). Most of the programs have at least one botanist. Keeping up-to-date with all the rare plants in their jurisdictions is a tall order, however. Tennessee’s Natural Heritage Botanist, David Lincicome, has stated that it would take 19 years to monitor and update all rare plant population records in the state! According to our June Conservation Champion, Anne Frances of NatureServe, “Programs are always interested in learning and documenting newly discovered rare plants and rare plant locations,” and the opportunities for partnership are vast. The data for these programs then feed into the NatureServe database and inform NatureServe’s status assessments (determinations of how rare or threatened the plants are).

In California, a state tracking more than 2,400 rare or threatened plant taxa, partnerships are key to data collection. The botanists of the California Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB) rarely collect their own data. Instead, a large part of their job is to help others to submit their data to CNDDB and to encourage them to collect additional information. According to CNDDB botanist Kristi Lazar, a big focus is on getting data on population size and threats. These are “two key pieces of information that are often lacking from data submissions” but are clearly important for assessing conservation status. CNDDB has collaborated with partners in data collection to develop an app that encourages more complete population reports aligned with CNDDB fields.

In New England, members of the Native Plant Trust (formerly the New England Wild Flower Society) work as part of the New England Plant Conservation Program (NEPCoP) to provide quality data to their Natural Heritage Partners. Through cooperative agreements, Heritage Programs in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont share their data with the society. In turn, NEPCoP volunteers and staff update records by visiting known populations of rare plants and submitting their data for botanical inventories or new discoveries.

Getting current data on known populations has proven challenging in many places. In California, as with most states, the program is a key resource for people developing environmental impact reports and conducting research on particular species or habitats. Botanists conducting surveys for these projects use CNDDB data to visit a reference site (known location), familiarize themselves with the species, and determine appropriate timing for their surveys and research. Unfortunately, many of the botanists don’t think of this data interaction as a two-way street. They may consider this location to be already documented and not see a need to submit their updated observations to CNDDB. In reality, new data are vital for tracking long-term trends in known populations.

Understanding trends is critical for another vital function of Natural Heritage Programs—determining species’ state-level conservation status. These statuses correspond to the subnational status (S ranks) within NatureServe and may be tied to state-level protections. Here again, partnerships can be key. In California, the California Native Plant Society (CNPS, a CPC Participating Institution) takes the lead on assembling status reviews with staff from CNDDB, CNPS, and other experts to determine whether new species should be added or an existing species should change rank or be removed.

Similarly, NatureServe uses data from Natural Heritage Network programs and experts to review and improve the National and Global Ranks. Anne Frances states that they welcome expert feedback, expertise, and collaboration—particularly on imperiled species—and that CPC Participating Institutions have a lot to offer. She also believes that NatureServe’s aggregated dataset can help CPC identify species to be included in the National Collection and prioritize the species most in need of ex situ collections.

CPC institutions have built a variety of relationships with Natural Heritage Programs. Native Plant Trust has built relationships with the numerous programs in its region. Conversely, California, CNDDB works with numerous CPC institutions: history ties it closely with CNPS. CNDDB botanists rely on the excellent data generated by the California Botanic Garden (formerly Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden) and knowledgeable help from herbarium curators during checks. But no matter how the relationships are built, a state’s Heritage Program is an incredible resource for conservation.

In most states, the Heritage Program provides the only comprehensive dataset with a high standard for accuracy that covers the status and locations of rare plant species for that state. For example, California plant data are reviewed by two biologists for accuracy. Heritage programs work to become “one-stop shops” for rare species data by incorporating all data on each rare plant species, including field surveys, reports, collections, photos, etc. The high quality of the data make these databases important tools for conservation science and informed decision-making.

The Natural Heritage Network has proven itself worthy of its name, as an essential resource that strengthens our ability to pass our natural inheritance to future generations.

As Seen on CPC’s Rare Plant Academy

As plant conservationists, we work to keep rare plants from the brink of extinction. While it’s always tempting to forge ahead with the work in front of us, we know that taking time for documentation is critical. Accurate records help us learn from our actions and share key information with colleagues, who are also doing their best to protect plants.

Happily, the CPC Best Plant Conservation Practices to Support Species Survival in the Wild includes a section devoted to this subject. “Documentation and Data Sharing” covers a wide range of documentation needs, from propagule collection to propagation, experiments, and back to the wild for reintroduction. The practices outlined here will enable you to secure useful data to further your conservation program. And by sharing data with your CPC and other partners, you will help inform and advance the science of plant conservation.

DOCUMENTATION AND DATA SHARING

A Rose by Any Other Name

Yes, a rose by any other name would smell as sweet. But would people know which beautiful bud you referred to? Naming and defining plants—or plant taxonomy—is essential to our understanding of plant evolution, relatedness, geography, conservation, and rarity. Accurate plant taxonomy is important when keeping data, and especially when sharing data. Make sure that rose means the same flower to those receiving the data as it does to you! Database managers need to check the names of species in their datasets against up-to-date taxonomies regularly, because names change more often than you might think.

As we learn more about plants and discover new ones, we are able to better refine our understanding of the relationships between them. New genetic data can split a genus, or merge two. Sometimes a whole family can be moved under another. For example, the former maple family (Aceraceae) is now recognized under the soapberry family (Sapindaceae). Because nature is not easily understood, defined, or categorized, experts have varying viewpoints on plant relationships and the names that represent those relationships. Although taxonomic experts do take time to meet, discuss, and agree upon changes based on the prevailing science, communication and general acceptance of these changes can be a thorny task.

The name changes definitely present a challenge for database managers. Taxonomic lists that report currently accepted names also make a point of listing current and former names (synonyms) for each plant species. Synonym cross-referencing helps botanists keep up with changes. Below is the list of taxonomic resources that CPC relies on to make sure we call a rose a rose.

1. ITIS. A very robust taxonomy reference for North America (with fairly good global coverage as well), ITIS includes names for animals, fungi, and microbes as well as plants. It is maintained in partnership with many US, Canadian, and Mexican agencies, including the Smithsonian and United States Geological Survey.

2. Plants of the World (POTW) and the World Checklist of Vascular Plants (WCVP). These resources, maintained by Kew, focus on comprehensive global coverage of plant names. WCVP (formerly known as The Plant List) is the taxonomy backbone, while POTW includes herbarium images and maps.

3. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Plants. Interestingly, the USDA maintains a database separate from ITIS. While it does include a large amount of taxonomy information, its strength is the wealth of images and plant trait data.

4. Regionally specific floras. The Jepson Flora is a key resource for CPC’s work with California Plant Rescue. Maintained by Jepson Herbarium at UC Berkeley, it is the primary taxonomy of state regulation in California.

5. The Flora of North America. CPC’s list of rare species will eventually conform to this taxonomy. A new website is available in Beta.

Anne Frances, Ph.D., Lead Botanist, NatureServe

As the botanist coordinating the plant species information for NatureServe, Dr. Anne Frances has helped refine standardized methods and data structure that allow aggregation of national and international datasets to achieve a bird’s eye view of plant conservation in the United States. NatureServe data allow us to see trends of species in various habitats that help assess their global, national, and regional ranks. Dr. Frances has spearheaded efforts to examine potentially overlooked regionally rare species and improve effective conservation through connecting information from garden collections to wild population assessments. In the U.S., she heads efforts to list rare plants in the international IUCN system, including some beloved medicinal plants.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I grew up in Miami, Florida, and spent a lot of time outside as a kid. There is always something blooming in Miami, and almost always some delicious fruit to eat. (Side note: Right now it’s mango season!) In hindsight, I have always been interested in plants, but I had no idea I could be a botanist until I was in college. Still, I remember collecting air plants (Tillandsia species) on a Girl Scout camping trip because I was fascinated by them. (I did not know it was illegal to collect plants without permission.) We carefully attached the air plants to trees in our yard and watched them grow. I also got my first of many terrible cases of poison ivy on that trip and quickly learned how to identify that plant!

During college at UNC-Chapel Hill, I took a horticulture class that had local flora as a major component. I loved it and was thrilled to learn you could earn a living hanging out with plants!

What was your path to becoming a botanist with NatureServe?

My path to becoming Lead Botanist at NatureServe was long and winding. After finishing my bachelor’s at UNC Chapel Hill and backpacking in Asia, I interned at the North Carolina Botanical Garden. My experience there very much influenced my path towards conserving native plants. The concept of a native plant garden was new to me, and their “Conservation Through – Propagation” slogan stuck with me all these years.

After college, I insisted I would never go back to school and never live in Miami again. I moved to Washington, D.C., and worked at the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation managing grants. Two years later I had an itch to return to field work and pursue yet another interest I could not seem to shake—ethnobotany. So, I applied to master’s programs and found myself attending graduate school at Florida International University (FIU) in Miami. Never say never!

My master’s work at FIU was an incredibly rewarding and humbling experience I conducted my master’s research in Costa Rica, studying the home gardens of an indigenous group called the Ngobe (or Guaymí) and their non-indigenous neighbors. My time at FIU solidified my interest in botany and conservation, which was bolstered by the partnership between FIU and Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden. During this time, I also worked as a field botanist for the Institute for Regional Conservation and in the seed lab at Fairchild under Joyce Maschinski, where I first learned about CPC.

While I still have great interest in tropical botany and ethnobotany, working in Costa Rica ironically made me pivot my interests back to plant conservation in the United States. Witnessing the development in Miami throughout my life, coupled with the scientific knowledge of how development has impacted species and ecosystems, fueled a drive to work towards conserving plants in my own backyard. Thus, I followed an opportunity to pursue a Ph.D. working with a professor at the University of Florida (UF) to research the establishment of native wildflowers on roadsides.

From the beginning of my Ph.D., I knew I did not want to pursue the path of becoming a tenure-track professor. I wanted to do applied conservation and felt my career interests would be best met at a botanical garden, government agency, or non-profit organization. I had long thought that NatureServe would be a great fit for my desire to work on applied plant conservation and actually started my position there in October 2010. I find it hard to believe that almost 10 years have flown by.

What do you see as the role of NatureServe within conservation?

NatureServe’s data, along with data from our network, provide the backbone for conservation decisions in the United States and Canada. We often take for granted the knowledge of which plants are globally or locally rare and where they occur, but this information would not be readily available without the NatureServe Network. NatureServe makes the accumulation of vast and varied datasets easily accessible through compilation, curation, standardization, and interpretation. Without these steps, it would be nearly impossible to aggregate data across North America and assign conservation status—each user would need to compile, curate, standardize, and aggregate each data set of interest individually. We would all have a much harder time knowing where to focus our limited conservation resources.

What has been the most challenging aspect of your work? And how do you overcome it?

The most challenging aspect of our work is lack of funding and resources. There is so much to do, and not enough staff or funding or time to do it all. It can be overwhelming. Sometimes it can feel like trying to roll a boulder up a hill. Overcoming this challenge is a daily exercise that often involves stepping back for perspective and engaging with my awesome team at NatureServe and the larger plant conservation community. Sometimes you need someone else to hold the boulder in place while you take a break. And if that does not work, I channel Dory from Finding Nemo and “just keep swimming.”

What has surprised you about working with plants?

Two things have surprised me. First, there is so much we still do not know about so many plants—from the most basic questions, like whether a species is extinct or still extant, to more complex questions, like why it grows where it does and how it germinates. Second, it is amazing how variable and boundary-pushing plants are. For example, many plants regularly engage in both sexual and asexual reproduction or switch back and forth between the two depending on their environments. If we consider this from human perspective, that can be mind-blowing. The fact that some plants can hybridize across genera, let alone species, poses a serious challenge to the biological species concept. Another example comes from our work on the Global Tree Assessment, for which we are developing a list of trees for the U.S. It may seem straightforward to determine what a tree is, but this can be quite complicated, as some species can be trees in one habitat and shrubs in others. Do you include tree-like species such as the Saguaro Cactus and tropical tree ferns? We will be presented with challenges any time we try to fit living things into boxes, but plants provide some fascinating examples!

What current projects or approaches in plant research or conservation excite you most?

One of the most exciting projects we are working on is developing innovative ways to efficiently update the conservation status of North American plants. With a flora of nearly 20,000 plant taxa, maintaining up-to-date conservation status can be daunting with only five botanists on staff. With support from the Brico Fund, we are looking at ways to increase the efficiency of reviewing ranks by streamlining and automating more of our process. The project focuses on updating Global Ranks of some of our most imperiled plants and using the new tool we’ve developed to “port” the underlying assessment data from NatureServe’s database to the Red List database. We are also partnering with SAS to investigate using Artificial Intelligence to assist with some of the compiling, curating, and standardizing work we do. This work will ultimately help us complete our goal of having up-to-date global status assessments for our entire flora!

All photos courtesy of Anne Frances.

Legislation to Protect our National Parks and Public Lands Will Save Plants

We are so close, but not quite finished.

On June 17, 2020, thanks in large part to advocates like you from across the country, the Great American Outdoors Act (GAOA) passed the Senate by a vote of 73-25.

On June 4, 2020, the companion bill (HR.7092) was introduced by a bipartisan group of 12 members in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Vote in the House is scheduled sometime before the end of July.

This legislation would fully and permanently fund the Land and Water Conservation Fund and address the critical backlog within national parks and other public lands, a majority of which are historic structures in need of repair. It would create jobs and bolster local economies through conservation and maintenance work on public lands. The Great American Outdoors Act is important for plant conservation because it contains language that requires native plants and natural infrastructure to be used in the projects funded by the bill.

If your Representative has cosponsored the bill, please call them and thank them and ask for their continued support for this important conservation legislation.

If they are not already a cosponsor, please ask them to sign on.

Take Action NOW

Find the contact information for your Representative. Call or Email them.

Let your Representative know that plant conservation is important to you and ask them to:

- Cosponsor and Vote YES for the Great American Outdoors Act (HR. 7092)

- Attend the vote in person

- Support a clean bill with no amendments

Ask your friends and family to contact their Representatives to support the Great American Outdoors Act and plant conservation.

For more information, see Center for Plant Conservation Advocacy page.

The Center for Plant Conservation Advocacy Committee tracks federal legislation that has direct impact on the safeguarding of rare and endangered plants. Please stay tuned for developments. We may need your voice to save plants.

Species Sponsorship

The Henry Shaw Cactus and Succulent Society Board of Directors donated $2,000 to the Center for Plant Conservation towards the sponsorship of two species – Navajo Pincushion Cactus (Pediocactus peeblesianus var. peeblesianus) and Short Leaved Dudleya (Dudleya brevifolia).

The Center for Plant Conservation plant sponsorship program is designed to provide support to the Participating Institutions providing the care or conducting research on the imperiled plants in the CPC National Collection. Currently, of the 1,600 plants in the National Collection, 276 are fully sponsored.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Employment Opportunities

Seeking additional candidates for Global Center for Species Survival in Indianapolis

Dear Fungi, plant, amphibian and reptile specialist group leaders,

I am happy to report that we have received over 200 applications for the seven Global Center for Species Survival Conservation Coordinators. We have thus begun the initial selection process with the purpose of hiring by the end of next month.

The list of candidates for plant/fungi and reptile/amphibian candidates are the shortest. If you know of any suitable applicant, please point them to the links below, and help us find the best possible people for the job!

Many thanks!

Jon Paul Rodríguez, Ph.D.

The Wildlife Tech 2 will assist with restoration efforts on Ohopee Dunes WMA and other WMAs in the Fort Stewart-Altamaha Significant Geographic Area for longleaf pine for the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Deadline to apply is 7/27/20.

Aspen Ecology & Conservation: The Changing Landscape of a Keystone

Abstract: To know western forests is to understand the outsized role played by quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides

Michx.) communities. As ecologists, we understand the natural bounty of aspen systems, but it is important to fully

appreciate the value of these forests to society at-large. This presentation will look at values to people and ecosystems in

the context of an evolving science and conservation of aspen. We will review basic ecology, research developments, and

adaptive monitoring in contemporary forest stewardship. There are many threats to sustainable aspen forests, including

past management, herbivory of wild and domestic ungulates, recreation and development, a changing climate, and lack of

coordination at ownership/boundary lines. A key tenant across natural resource fields today is multi-species management;

in other words, putting “systems thinking” to work. The Western Aspen Alliance (WAA) advocates monitoring and

collaboration as central practices for effective management in aspen communities. Cross –agency, -boundary, and –

discipline work will govern the future of sustainable aspen ecosystems. At the global scale, we will briefly discuss how

aspen practices discussed here are being shared around the world under the “mega-conservation” banner. In sum, the

WAA encourages conservation practitioners to take advantage of this service through participation, sound practice, and

feedback.

Evaluating Native Seed Mixes for Post-fire Seeding in the Great Basin.

Abstract: Post-fire seeding has been widely implemented in the Great Basin in response to the threat of resource

degradation and weed invasion following fire disturbance. The longstanding practice of seeding non-native forage grasses

has worked well for some purposes, but seeding native species is a more sensible choice if natural vegetation recovery is

a long-term objective. Seeding natives raises questions of cost, establishment ability and whether native species will be

as effective as non-natives in outcompeting invasive annuals. We consider these issues in the context of a study where

outcomes of native and non-native seed mixes were compared during an 18-year timeframe following wildfire.

Successional trajectories of seeded treatments were compared with unseeded controls and late-successional reference

communities to assess restoration potential of treatment options.

Ways to Help CPC

Support CPC by Using AmazonSmile

As many of us are now working from home and relying on home delivery more and more, we wanted to remind you that you can keep your home stocked AND SavePlants. If you plan to shop online, please consider using AmazonSmile.

AmazonSmile offers all of the same items, prices, and benefits of its sister website, Amazon.com, but with one distinct difference. When you shop on AmazonSmile, the AmazonSmile Foundation contributes 0.05 percent of eligible purchases to the charity of your choice. (Center for Plant Conservation).

There is no cost to charities or customers, and 100 percent of the donation generated from eligible purchases goes to the charity of your choice.

AmazonSmile is very simple to use—all you need is an Amazon account. On your first visit to the AmazonSmile site, you will be asked to log in to your Amazon account with existing username and password (you do not need a separate account for AmazonSmile). You will then be prompted to choose a charity to support. During future visits to the site, AmazonSmile will remember your charity and apply eligible purchases towards your total contribution—it is that easy!

If you do not have an Amazon account, you can create one on AmazonSmile.

Once you have selected Center for Plant Conservation as your charity, you are ready to start shopping. However, you must be logged into smile.amazon.com—donations will not be applied to purchases made on the Amazon.com main site or mobile app. It is also important to remember that not everything qualifies for AmazonSmile contributions.

So, stay safe inside, and when ordering online, remember you can still help save plants. Please feel free to share this email with your friends and family and ask them to select Center for Plant Conservation.

Thank you all for ALL you do.

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today