If your plants don’t have records, do they exist? San Diego Zoo Global

Rare plant collections require a daunting combination of skill, time, and luck. To ensure that this hard work provides the maximum possible value to the conservation community, collectors must maintain detailed and shareable records.

Philosophers have long asked, “If a tree falls in the wood and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” As a plant conservationist, it’s hard to answer this question without a botanical bent: For me, the death of a plant (especially a rare one!) makes a philosophical and ecological impact that can be “heard” even if no one directly observes it. This belief is shared by our community of conservationists who scale cliff faces, trek through brambles, and endure mosquitos-laden swamps to collect the seeds that ensure the survival of rare plants species. During these hectic field trips, the mundane process of recording details about the location, habitat, and habit of the plant may fall by the wayside. Similarly, the data entry of field records might take a back seat to day-to-day work place deadlines. However, to all those with data languishing un-entered in their lab or green house I ask, “If you collect a plant and no one has time to document it, does it still have conservation value?”

Without detailed, shareable plant records, a plant collection is unlikely to help save a species from extinction. For instance, location information is critical to assessing where a population of plants could be reintroduced in to the wild, and germination records are the best way to estimate the quantity of seeds needed for such an effort. In addition, sharing plant records across institutions can prevent duplicate collections of already rare plants species, and ensure that the limited resources available for plant conservation are being used efficiently. Finally, plant collections records are the basis of much of the current research into species distributions and migrations due to global climate change. By providing accurate collections data, conservationists facilitate additional research about the rare plants they are working to save.

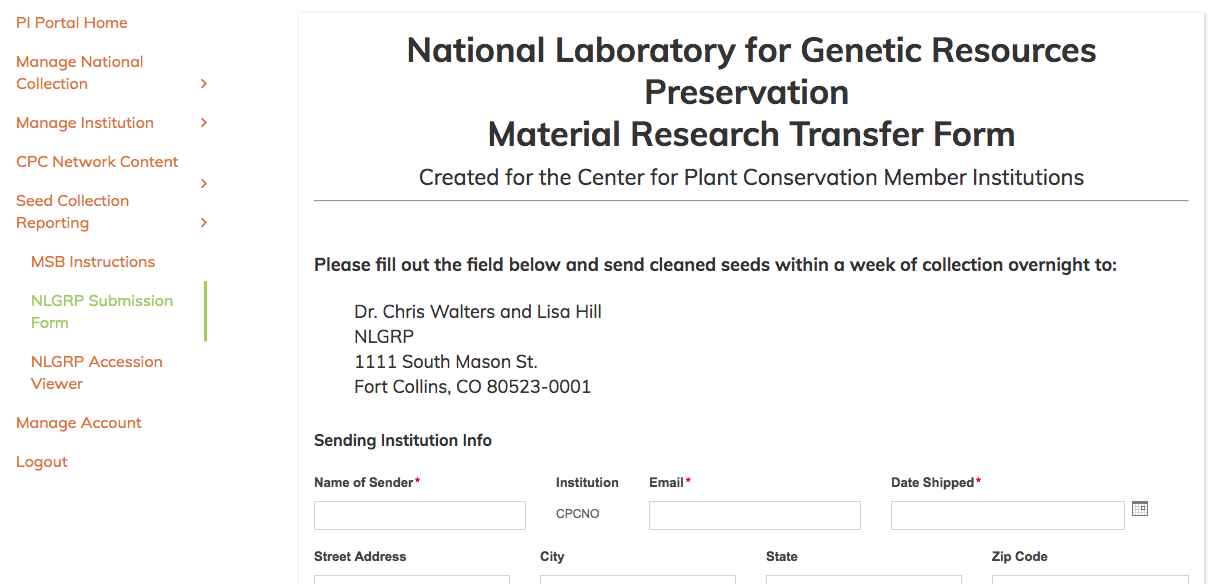

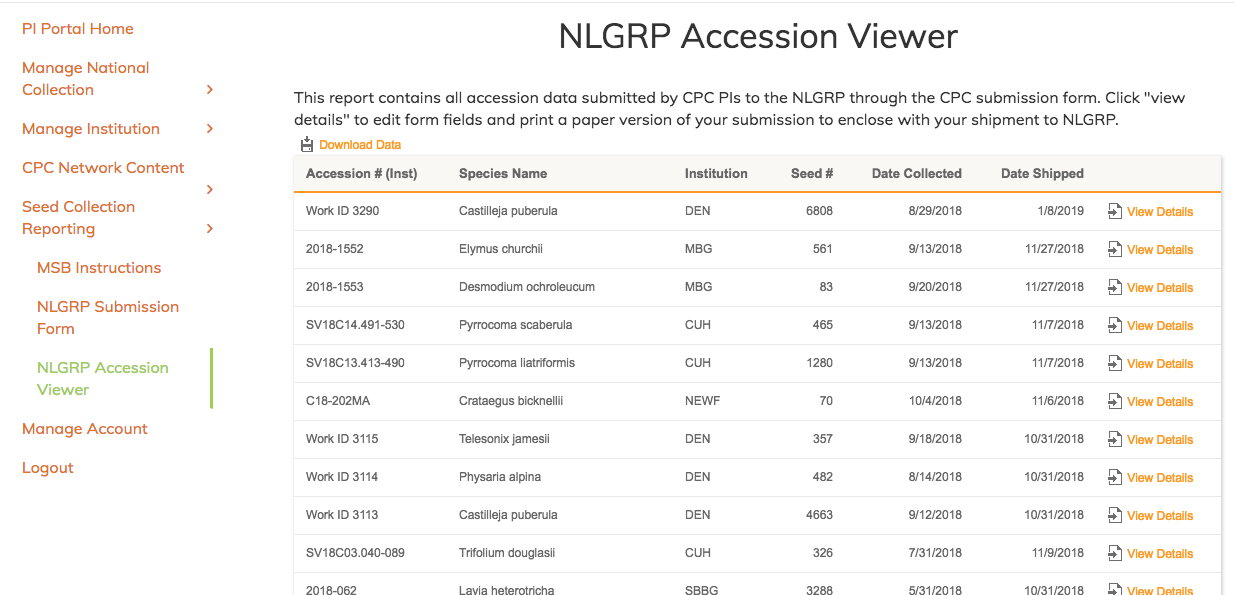

CPC has developed a set of tools to help our network of plant conservationists record and share high quality rare plant records. In the “Documentation and Data Sharing” portion of CPC’s Best Plant Conservation Practices to Support Species Survival in the Wild, our best practices guidelines, we provide a field collection form that outlines the information that conservationists should make at the time of each plant collection, as well as describe other best practices for data collection and management. We also provide an electronic form in our CPC Participating Institution (PI) web portal that allows CPC Conservation Officers to transmit collection data directly to the National Laboratory for Genetic Resource Preservation (NLGRP), where our institutions send “back up” allotments of rare seed. By using this form, our PIs are not only facilitating the seed research of NLGRP, but they are also communicating their collections with a community of plant conservationists. Sharing data helps track progress on collective goals and allows for more people to learn from the data.