Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

February 2019 Newsletter

For our February issue of SavePlants, we take a look at some of our imperiled plants that challenge our notion of what a “relationship” should be. You see, there are plants among us that are parasitic – those plants that derive all or part of their sustenance from other plants in their environment. These parasite-host relationships sometimes result in a sustained co-existence with minimal host harm while other times, well, it’s not quite so benign. But parasitic plants provide valuable ecological roles and are a fascinating albeit often misunderstood part of the natural world. Parasitic plants present a unique conservation challenge as we need to both understand and preserve the parasitic plant itself and also the host species these plants depend on. What is clear is that relationships like these are not always what they seem and deserve our help like all other imperiled plants on this planet. Read on to learn about these plant relationships and enjoy the more tongue-in-cheek tone of this month’s newsletter. Happy Valentine’s Day from all of us at CPC.

Volunteer’s Love of Plants Helps Conserve Parasitic Vine

Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center

Based on an interview with Nan Hampton, Ph.D., volunteer

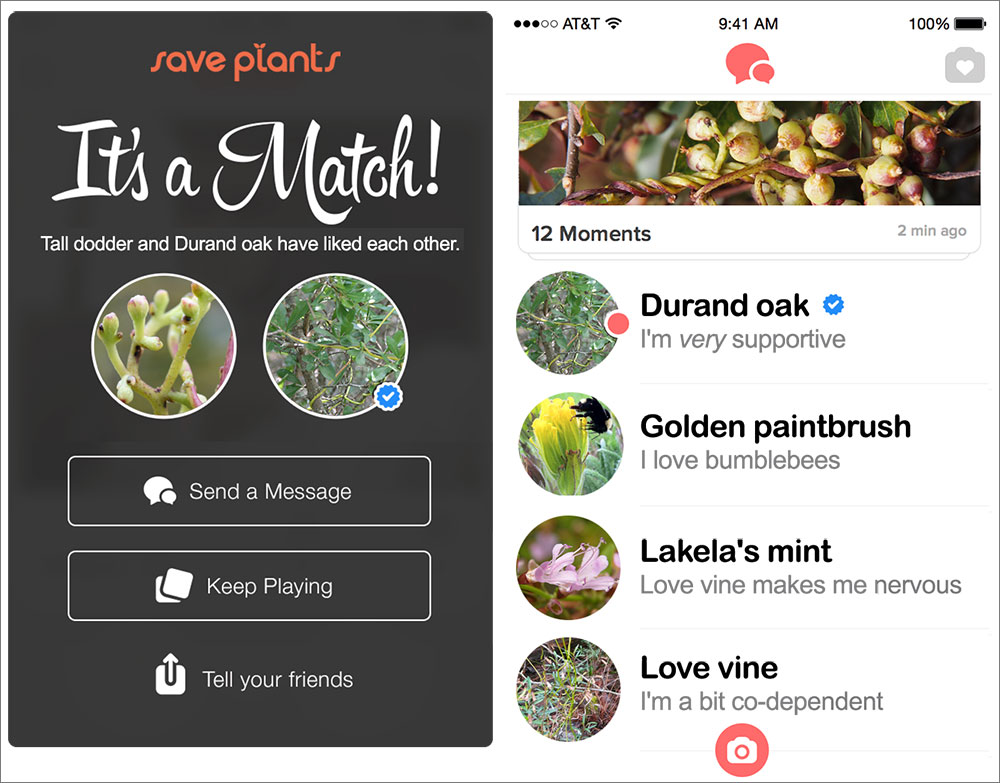

Plant Dating Profile: Tall dodder

Name: Cuscuta exaltata

Location: Florida and Texas

About me: I’m a vine and a pretty rare find – my populations are small, though spread over a wide range. As a new germinant without a good ability to photosynthesize, I need to find a host to support me fast! I am an ectoparasite and make my home on my host, attaching myself with my haustoria. My life is short and I’m looking to make a life-long connection as soon as possible.

Looking for: Woody plants! Give me a tall, dark and handsome oak, walnut, or sumac, and I’m pretty happy. Though I also don’t mind grabbing on to coarse herbaceous plants. All I really need is a good source of nutrition.

Likes: My favorite color is orange, because I am orange! Well sometimes I am… I don’t make much chlorophyll and can be orange, yellow-ish green, and even mature to magenta. I like twisting and twining my way along sturdy branches.

Dislikes: Habitat destruction! I’m tired of losing good host trees to put in a new field or town. Also… I’m not a big fan of people removing me from my host. They seem to think I’m trying to kill my host. I mean, I know they’re just trying to protect their plants, but I promise I rarely form the dense tangles that will actually do harm – I want my relationships to last!

As with many parasitic plants, many people see tall dodder (Cuscuta exaltata) as a pest. Removal by landowners is even a reported threat to the small populations of this vulnerable vine. Fortunately for the tall dodder twining around the shinnery oaks of a knoll on a 259-acre ranch outside of Lometa, Texas, Nan Hampton’s discovery of the vine elicited excitement rather than a desire to remove the plant. Besides managing the ranch with her husband, Nan is a long-time volunteer at Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center (LBJWC). She was working with local botanist Laura Hansen at the time of their discovery in 2009 to conduct a thorough botanical inventory of the ranch. Both her volunteer work and botanical inventory were fulfilling a latent desire to work in botany after years in pursuit of and later applying her doctorate in zoology.

Nan was introduced to LBJWC by a former doctoral student at the University of Texas during her time there, Damon Waitt, who became a good friend and, later, Senior Director and Botanist at LBJWC (and eventually Director of North Carolina Botanical Garden, another CPC Participating Institution). Upon receiving his position, he informed Nan that she would be volunteering with them when she retired, and she did not argue the pronouncement. Though a lot of her time volunteering at LBJWC was contributing to the Mr. Smarty Plants outreach program, she was also able to participate in plant surveys and seed collections for the program established with the center’s partnership with the Millennium Seed Bank. When Minnette Marr, Curator of the Seed Bank at LBJWC, expressed interest in getting a seed collection from the population, after Nan reported her rare plant discovery, Nan was more than willing and able to take the task on.

After watching the development of the flowers and fruits through the 2010 growing season, Nan and her family – husband Loyd Hampton and daughter Lisa Hampton Schmidt trekked out to the knoll with a ladder and pruners ready to collect. The tall dodder was wrapped along the higher branches of various oaks in the shinnery, making it difficult to reach, so they carefully snipped the branches of the oak to be able to retrieve the ripe fruit. An annual, the dodder was already senescing or starting to die off, and not impacted by the collection and the oaks weathered it well. The dodder’s seed made it back to LBJWC’s Seed Bank, where it joins the 100s of other Texas species in the collection. The Wildflower Center Seed Bank is largely built on the cooperation of private landowners and the enthusiasm of trained volunteers – but they aren’t always the same person.

Hoping to eventually publish their work, Nan continues to work with Laura as well as to volunteer at LBJWC, saying “I think I wanted to be a botanist all along, and didn’t know it!”. Though she hasn’t seen the dodder come back, other rare plants have continued to call the ranch home, including silver mercury plant (Argythamnia aphoroides), of which there are 20 known occurrences and probably less than 10,000 plants, and a locally rare population of white trout lily (Erythronium albidum) on the edge of its range.

-

Tree dodder formed tangles in the shinnery oaks, making it necessary to trim branches of the oaks in order to extract seed. -

Cuscuta exaltata fruit. Tree dodder fruit on the vine. -

The twisting vine of tree dodder bearing fruit. -

Cuscuta exaltata flowers. -

Tree dodder twines its way around a Durand oak (Quercus sinuata). -

Cuscuta exaltata fruit. As the fruit ripens, both the vine and the fruit gain a red hue.

All photos courtesy of Nan Hampton, Ph.D.

Lots of Love for a Returning Oregon Native

Institute for Applied Ecology

Based on an interview with Tom Kaye, Ph.D., Executive Director

Plant Dating Profile: Golden Paintbrush

Name: Castilleja levisecta

Location: British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon

About me: I can be independent when I’m in a comfortable nursery, and I even make my own chlorophyll, but I have to admit that I am a hemiparasite and prefer a host to help support me. I love it when bumblebees come to my flowers! Though my flowers may not grab your attention, they’re tucked into bright yellow bracts that definitely will.

I’ve been listed as a threatened species in the U.S. since 1997 and have been getting some good help to get me back on my feet.

Looking for: Honestly, I’m pretty attracted to all kinds of plants and like to live in areas with a diversity of ‘significant others’ that I can tap into. I do pretty well with a variety of host plants, from grasses like Idaho fescue to perennials like woolly sunflower and yarrow. But flirty annuals need not apply, I’m looking for something long-term (though not necessarily exclusive).

Likes: I like prairie habitats – grasslands… but, I don’t like the grass and other vegetation around me to get too tall. I guess that’s why I flourish with regular flushes of wildfire.

Dislikes: Invasives encroaching on my spot, hikers and animals trampling me, people picking my flowers. And of course I loathe habitat destruction.

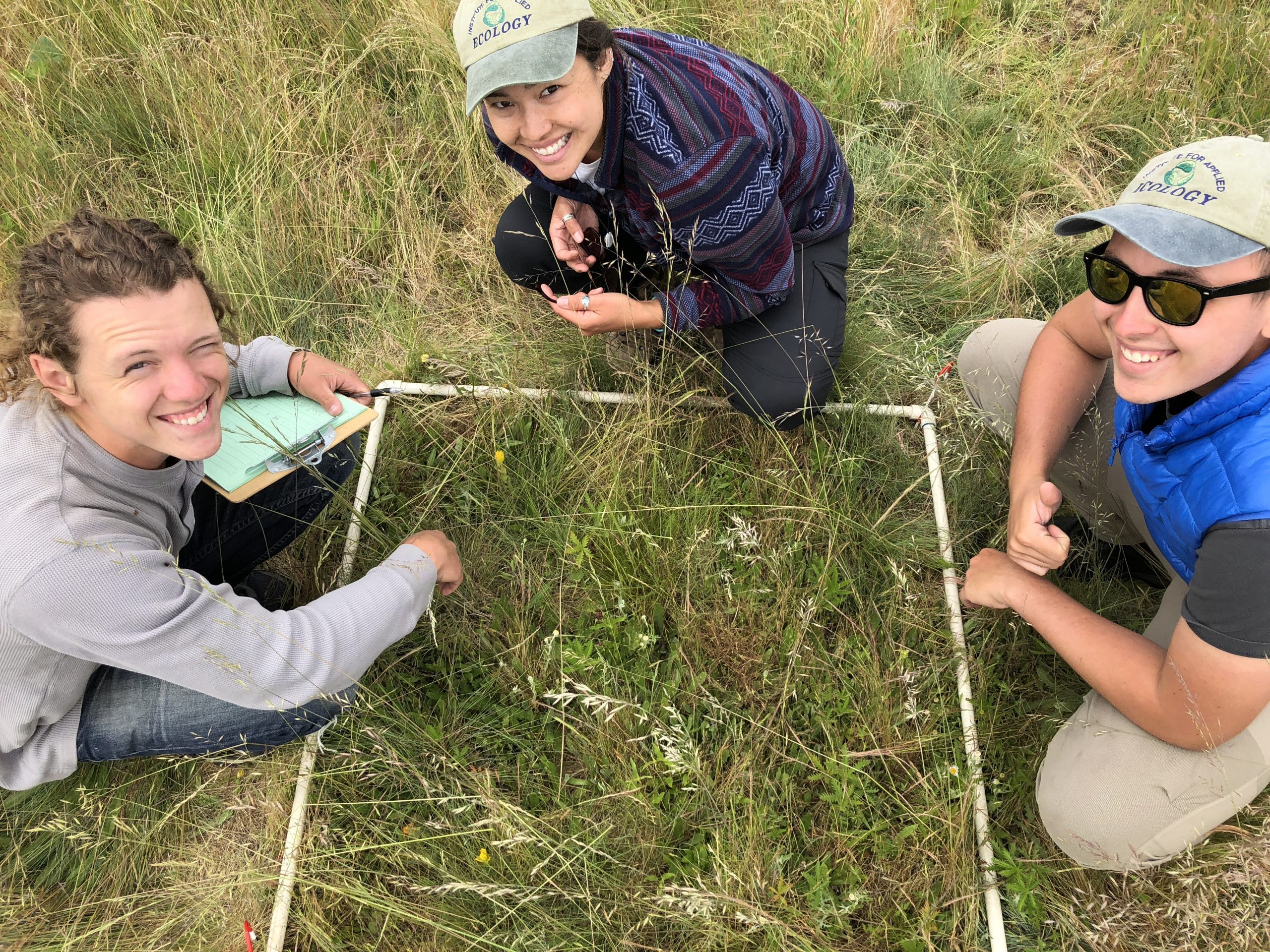

The last natural populations of golden paintbrush in Oregon were last recorded in 1938. But through the efforts of one CPC’s newest participating institution, the Institute for Applied Ecology (IAE) and its partners, there are now 23 reintroduced populations totaling some 360,000 individuals in the prairie grasslands of Oregon’s Willamette Valley. It took a lot of research and adaptive management to get to this point, including increasing the understanding of what this beautiful parasitic plant looks for in a host.

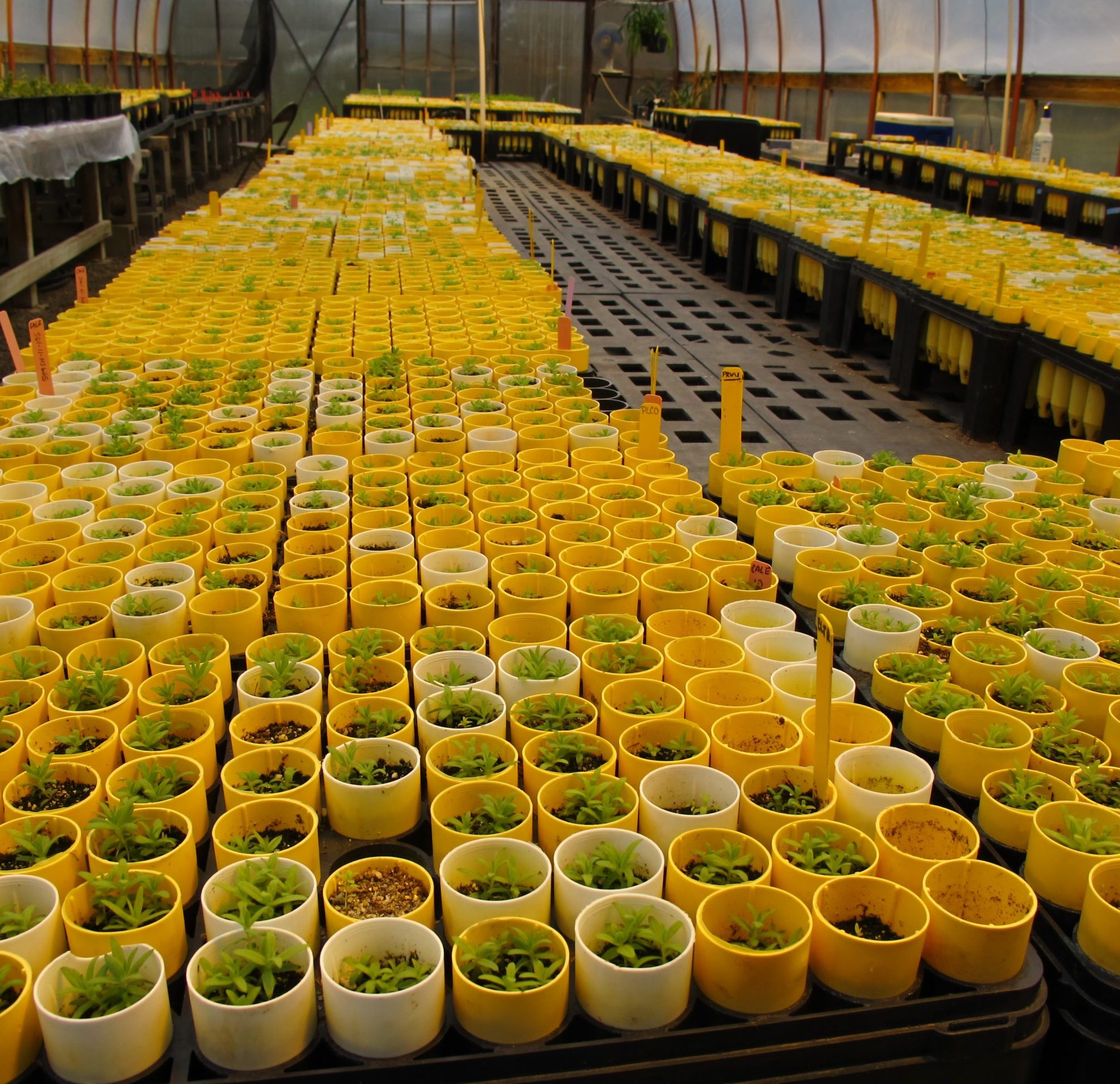

The efforts started in the nursery, where researchers paired golden paintbrush with over 12 potential host species. Proving itself not particularly picky, the propagated paintbrushes never failed to establish a connection with their host’s roots, regardless of species. Being a hemiparasite, it was also able to grow and reproduce in the nursery without a host. Yet, it undeniably thrives and produces more flowers when paired with a suitable host – and does not occur in the wild without one.

Having learned to propagate golden paintbrush, Dr. Tom Kaye, Executive Director of IAE, then worked with US Fish and Wildlife staff to figure out an approach for how to reintroduce the species back to Oregon. Finding suitable reintroduction sites, they then collected seed from populations in Washington. Through experimentation they found that plants from seed originating in sites that may have been further away in Washington but more similar ecologically, especially in term of the vegetation community, did best. They also learned more about golden paintbrush-host plant relationships.

For one, says Tom Kaye, it was clear that golden paintbrush is looking for a stable relationship: annual plants do not make good hosts. However, this doesn’t mean that they’re looking for an exclusive relationship. A golden paintbrush can attach to multiple host plants, and survival of reintroduced plants increases as the number, and diversity, of neighbors increases. Diversity of hosts seems to matter more than the identity of the host. For example, though woolly sunflower (Eriophyllum lanatum) is a good, and common host, a golden paintbrush attached only to this perennial herb could find its connection impacted in years when the local vole population surges, as the little rodents seem attracted to the sunflower’s roots. Attaching to several perennials allows golden paintbrush to buffer itself from potential problems.

All photos by Tom Kaye, courtesy of Institute for Applied Ecology.

As a result, sometimes IAE restores prairies along with their golden paintbrush reintroductions. When seeding an area with paintbrush seed, they will also seed various prairie bunchgrasses and perennial herbs. Establishing both at the same time allows golden paintbrush to establish with the community. When plant diversity is already high, planting plugs works as an alternative to seeding – though additional hosts may need to be planted as well.

The original reintroduction efforts occurred in 2004, but efforts ramped up in 2010 and success has come relatively quickly. It helps that there are also reintroduction efforts being conducted in Washington. There Dr. Peter Dunwiddie at University of Washington and with the Center for Natural Lands Management has come across similar challenges and results as IAE and the two programs have been able to learn from each other. As a result of the efforts in both Washington and Oregon, golden paintbrush’s chances of recovery are looking up. Though Tom expects some drop off in the populations after the initial boom following reintroduction, he is hopeful that this special paintbrush is back in Oregon for good.

Rare hosts beware! Love vine not so loving for endangered Lakela’s mint

Bok Towers Garden

Main article contributed by Cheryl Peterson, Conservation Program Manager

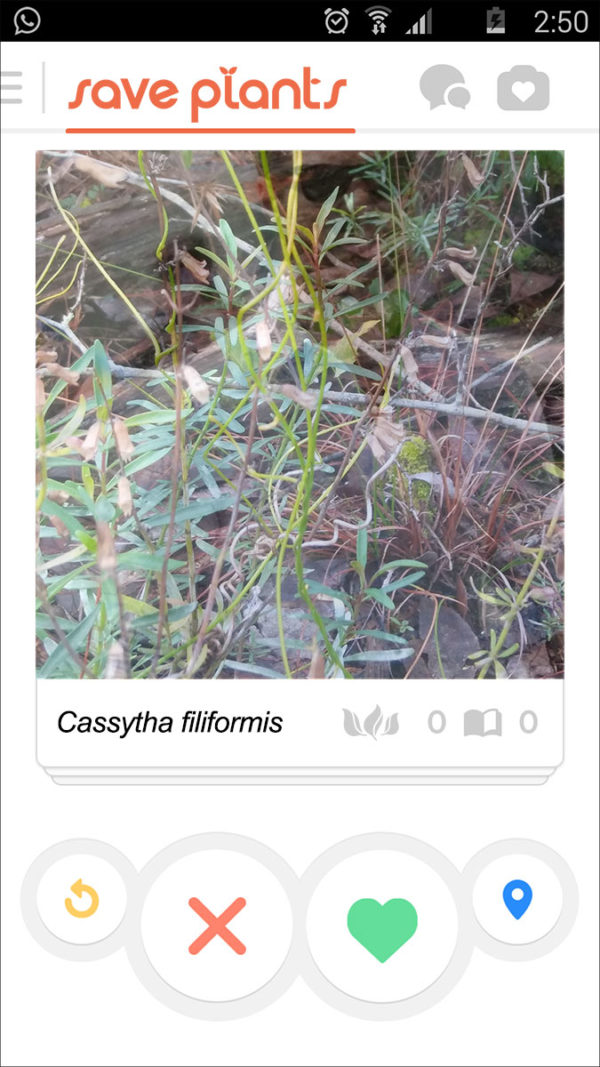

Plant Dating Profile: Love Vine

Name: Cassytha filiformis

Location: Florida, pantropical

About me: Some cultures from the Caribbean call me love-vine because, apparently, they think I have aphrodisiac qualities. I don’t know about that, but I like the name regardless… I’m pretty loving (though some may say smothering).

Looking for: I’m open to lots of possibilities – rare plants not excluded. I mostly cling to woody plants for their support – but don’t mind attaching to herbaceous hosts. I’m also open to connecting with many plants at the same time.

Not everyone can handle me, I demand a lot of my hosts, and unfortunately, some just don’t make it.

Likes: You can find me in the Caribbean, Africa, Australasia, just about anywhere with a coastal area in the tropics. I really love the chance to grow in the warm summer months of Florida!

Dislikes: Being confused for dodder – we’re not even in the same family! Also, volunteers removing me from their precious rare plants – can’t they mind their own business? Being called greedy or a mooch… apparently some people don’t appreciate me draining my hosts of water and nutrients, but I’m just taking what I deserve.

The endangered Lakela’s mint (Dicerandra immaculata) is known from only one natural population. This population exists in just five scattered fragments of remaining scrub habitat along a three-mile stretch of the Atlantic coastal ridge along Florida’s southeast coast. Millions of years ago, the different ridges of Florida were formed by rising and falling sea levels, and during periods of high sea levels, plants and animals began to adapt to, and then require, the special habitats that developed. Many species like the Lakela’s mint are historically known from just one ridge system and nowhere else in the world. However, because these elevated, sandy areas are also prime locations for development and citrus groves, many of their endemic species continue to be threatened and are critically imperiled. Most of Lakela’s mint habitat has been destroyed by development, and preserving habitat quality for the remaining populations is vital to its survival.

Scrub was historically subjected to periodic wildfires, which maintained both the canopy and sand gaps characteristic of this unique habitat. Unfortunately, Lakela’s mint now finds itself in an urban environment and their sites are thus difficult to manage by fire. As a result, even the protected populations have experienced heavy overgrowth of both native and invasive species.

One of the biggest threats to the survival of Lakela’s Mint is the love vine, Cassytha filiformis. The love vine is a leafless, climbing vine in the Lauraceae family which parasitizes a wide variety of plants throughout the tropics and subtropics worldwide. It has orange-green stems, is a perennial, spreads both vegetatively and through seeds, and rapidly grows into thick mats following the summer rainy season. It relies on other plant species for physical support, water and nutrients. It uses its haustoria to extract vital nutrients – and starve the host. Some species are more vulnerable to the love vine than others. Lakela’s mint is unfortunately extremely vulnerable, and large expanses of mints have perished within weeks of encroachment by love vine. While love vine may have minor impact on a few individuals of other species, for Lakela’s mint, it poses a major threat.

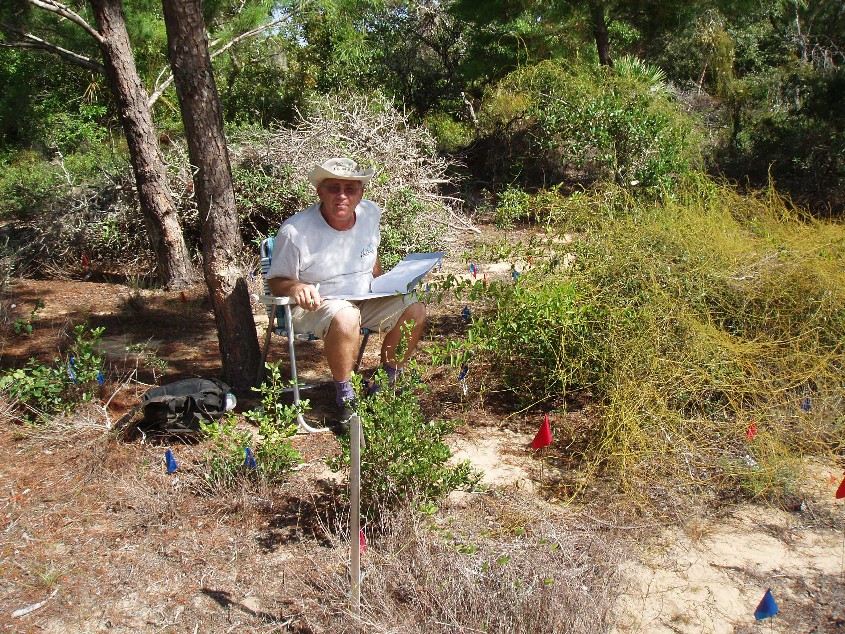

In lieu of fire, which historically helped control the spread of the love vine, Bok Tower Gardens and St. Lucie County now organize monthly half-day volunteer events to remove the love vine by hand. The vine is tediously picked from mint stems, and large handfuls are pulled from surrounding vegetation. All pieces of the vine, no matter how tiny, are diligently placed into bags that are then removed from the site, in order to prevent re-infestation. During the first event in 2017, ten volunteers removed 12 large yard waste bags full of love vine from the mints in less than two hours! Since then, love vine has been cleared from more than two-thirds of the mint population, and mint survival has drastically improved. However, because it can repopulate an area in just a few short months, ongoing, regular efforts to remove the love vine will be required to ensure survival of the Lakela’s mint.

Unhealthy relationships are hard to break free of and, in the case of love vine and this rare mint, it is going to be ongoing process. Fire isn’t likely to return to the habitat on a regular basis. Fortunately for Lakela’s mint, Bok Tower Gardens and their volunteers are dedicated to helping these lovely shrubs keep the love vine at bay.

Bill Brumback

Bill Brumback started his career at the Wild Flower Society in 1980 as Propagator, growing native plants for Garden in the Woods, the Society’s botanic garden, for plant sales, and researching the propagation and cultivation of rare species. The Society began to increase its conservation efforts, both in the wild and ex situ, and in 1991 he became the Conservation Director.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I came to plants later than most, after college when I worked in Holland with bulbs and perennials. I didn’t have any interest in plants before then, but after two years in Holland I was hooked. I liked the physical work and the intellectual challenge of learning plants from the roots up.

What was your career path leading up to your position as Conservation Director at New England Wild Flower Society?

After I returned from Holland in 1973, I became the Propagator for a wholesale perennial nursery in Maryland and planned to start a nursery with a buddy of mine who had been working in Holland with me. But, while looking for land for the nursery I started taking courses in botany and taxonomy. Eventually, I decided to go to graduate school and was accepted into the Longwood Program at the University of Delaware where I became interested in endangered species conservation and wrote a thesis about the topic. After Longwood, I started a job at the Wild Flower Society in 1980 as Propagator, growing native plants for Garden in the Woods, the Society’s botanic garden, for plant sales, and researching the propagation and cultivation of rare species. The Society began to increase its conservation efforts, both in the wild and ex situ, and in 1991 I became the Conservation Director. We started the New England Plant Conservation Program (NEPCoP), our regional plant conservation collaborative. NEPCoP brings together representatives from over 50 institutions with the goal of preventing the extirpation and promoting the recovery of the region’s rare plants.

What are a couple of the major threats/challenges facing rare plants in New England? How has your, or your institution’s, work addressed them?

New England has been impacted for a long time, having been almost 80% deforested in the 1800s. We now have more forested land than 200 years ago. Ironically, succession to forests is a major reason for the decline of some of our rare species, especially those that need open habitat. The largest threats are development/habitat destruction, alteration of natural systems (hydrology, fire regimes, etc.), and invasive species. Climate change is going to be a big factor, if it isn’t already. Maybe the biggest challenge is to promote the importance of conserving plants to the public.

Through the NEPCoP collaborative, we have focused on monitoring rare plant species, banking seed from selected populations, managing rare plant occurrences where possible, and augmentation/reintroduction/introduction of rare plants.

What about working with plants has surprised you?

The survival of the plants we’ve introduced and my lack of understanding of “suitable habitat.” I have introduced plants of rare species to areas where I thought the habitat was perfect, only to have them die. Conversely, some introduced plants have survived in places I never thought they’d make it. The plants are telling me that I really don’t understand what’s going on.

Please share one of your plant conservation projects.

Probably the project that received the most attention was conservation of Potentilla robbinsiana, Robbin’s cinquefoil, known from only two locations in the alpine zone of the White Mountains of New Hampshire. Federally Listed as Endangered, the main threats were over collection by early botanists, and more recently, hikers on a historic trail that ran through the population. The trail was relocated, and the Society grew plants from seed and reintroduced the plants. In 2003, with help from many other collaborators, including the CPC, the plant was officially removed from the Federal Endangered Species list because it met the recovery objectives for both the natural and reintroduced populations. I’ll leave you to debate whether a plant that only grows in two places in the world should ever not be considered “endangered.”

What accomplishment are you most proud of achieving in your tenure as Conservation Director?

I have never achieved anything without the help of many other people, primarily Society staff and NEPCoP collaborators. I’d rather applaud the efforts of many people and organizations in the following: NEPCoP (too many people to thank), Plant Conservation Volunteers – PCVs (thanks for proving that amateurs can play a large role in plant conservation if we only let them), Potentilla robbinsiana (see above – a conservation success story), Flora Conservanda: New England (the regional list of plants in need of conservation – a collaborative effort if there ever was one), Flora Novae Angliae (the Flora of New England –first regional New England flora in 60 years, written by the Society’s botanist), and Go Botany (the website based on the Flora that is flora of the future for New England in electronic form).

How has the world of plant conservation changed throughout your career?

On a national level, the knowledge and scientific rigor in plant conservation, particularly seed banking, has increased greatly over the past 30 years. This is due in large part to the CPC and its Participating Institutions.

In what area of plant conservation do you see the need for future research?

The role of fungus in plant life and survival. I think we are just at the beginning of understanding fungal associations and their relation to plant conservation. If I had to start over, I just might be into fungus (particularly in relation to terrestrial orchids).

What parasitic plant is first in your heart?

Agalinis acuta (sandplain gerardia) – Almost entirely restricted to graveyards (really!) in New England in the 1990s, we have introduced this hemiparasitic annual species to several protected locations, and it is thriving, probably because of disturbance (fire, mowing, etc.). Flowers are beautiful, short-lived (one day!), and pollinated by bumble bees. Recent taxonomic work has shown that this federally listed taxon may actually be part of Agalinis decemloba, and it may therefore be de-listed. Whatever its name, it will still remain rare in New England.

-

Bill monitoring Astragalus robbinsii var. jesupii. Photo by Jessica Gerke. -

Planting out the rare Robbins’ cinquefoil, a species delisted from the Endangered Species Act protection after some great conservation successes. Photo by Doug Weirauch. -

Isotria medeoloides le-dcameron. Little five leaves. Photo by Don Cameron.

-

One of Bill’s favorite parasitic plants, sandplain gerardia (Agalinis acuta), flourishes in graveyards. Photo by Bruce Sorrie. -

New England Wild Flower Society’s work with Robbins’ cinquefoil (Potentilla robbinsiana) was an early success within the CPC network. Photo by Doug Weirauch. -

Robbins’ milk-vetch (Astragalus robbinsii var. jesupii). Photo by Lisa Mattei.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today