Exceptional Collaborations to Save Exceptional Species

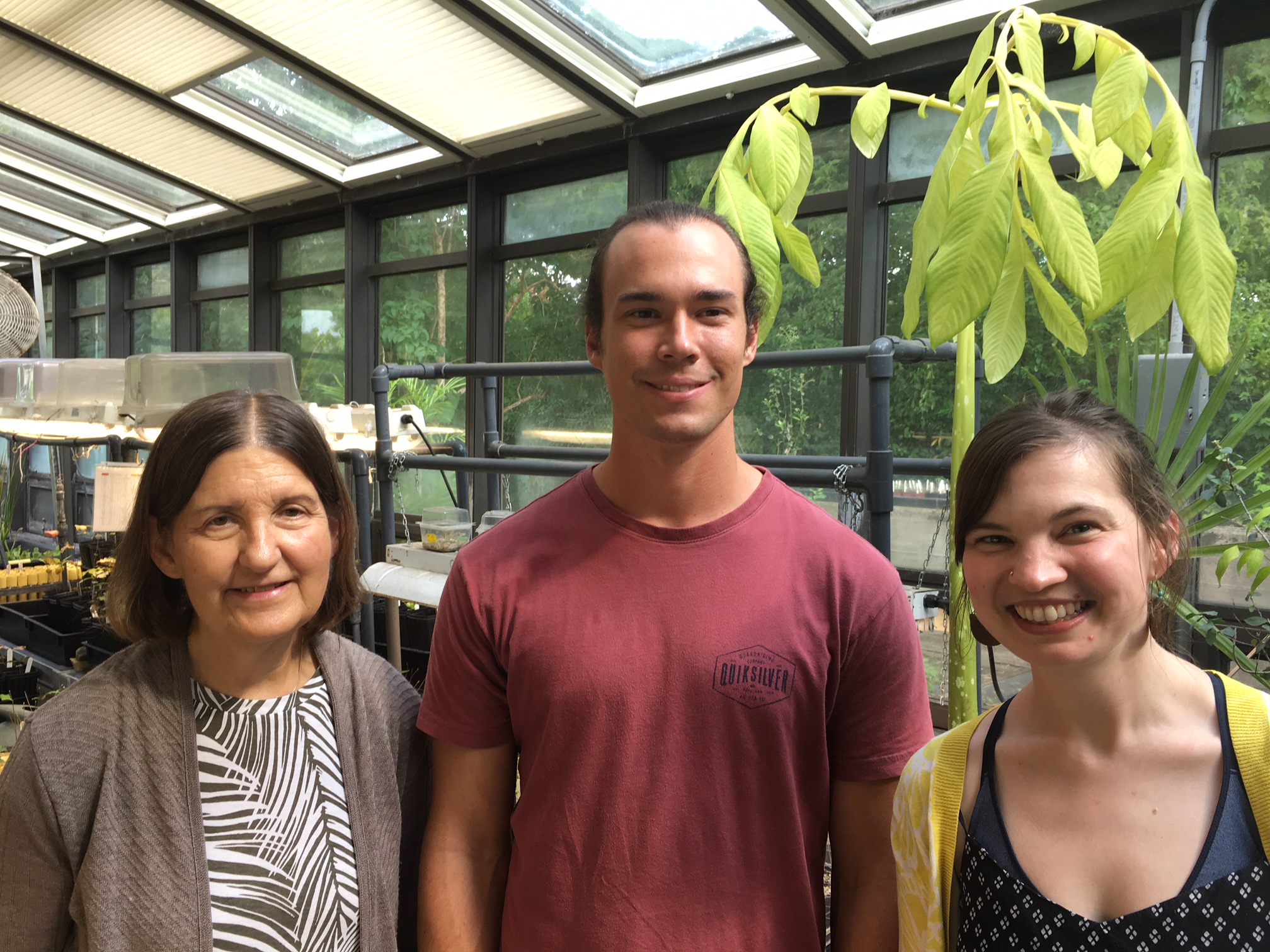

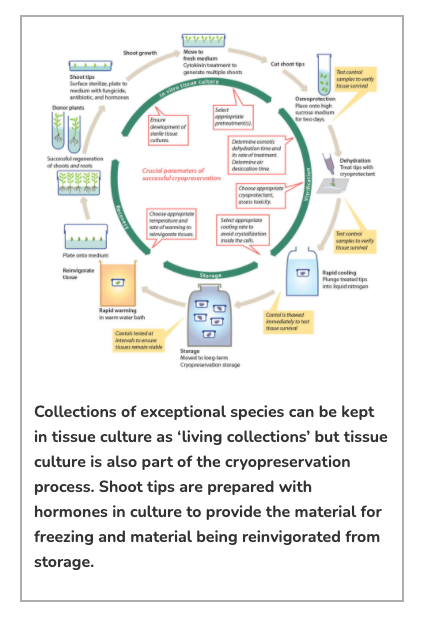

Nellie Sugii’s tissue culture facility at Lyon Arboretum in Hawaii has many of the same basic elements as the plant tissue culture lab at Cincinnati Zoo’s Conservation Research for Endangered Wildlife (CREW): both use artificial media in sterile tubes and jars to grow plants from tissue or seed. But upon visiting, Valerie Pence, Ph.D, Director of Plant Research at CREW, realized how different the labs were. The test tubes of plants Nellie and her team are grown with the goal of creating robust plants maintained as a living collection, which will be supported in subsequent generations by subculturing, or splitting the resultant plants into new plants. Valerie’s lab grows plants in tissue culture in order to get lots of shoot tips growing quickly, developing the material they need to cryopreserve the plants in liquid nitrogen (i.e., cryopreservation). While Nellie’s lab often forgoes use of hormones in the media supporting the plants to keep growth manageable, Valerie experiments with various hormones and changes to the media to find the right mix that rapidly promotes shoot tip production. The labs have different goals and thus different tissue culture techniques, but both methods are important in addressing the needs of many rare plants in Hawaii – and around the world – those known as threatened exceptional species (TEPs).

Tissue culture and cryopreservation can be used to support these TEPs to provide the same insurance as seed banking – providing plant material for research and reintroductions, and safeguarding a population as insurance. Seed banking has long been the cornerstone on which many plant conservation projects are built on, and yet, thousands of rare plants cannot be seed banked, hence they are the exceptions to the typical conservation approach. The challenges in fine tuning tissue culture and subsequent cryopreservation to the wide range of species needing them are great, and thus the plant team at CREW has been working to not only increase our understanding of these species but make sure more institutions are prepared to help conserve them. This project not only has CREW’s plant research team working with Lyon Arboretum, providing that very valuable insurance to the collections they have been keeping in tissue culture for years, but also has CREW collaborating with partners throughout the country.

CREW’s ambitious, multipronged project is being funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), as a primary goal helping botanical gardens learn more about and better maintain their collections. CREW is taking the lead in conducting research on identifying TEPs, promoting research within other institutions, establishing a network to build capacity and collaboration, and developing methods to conserve many Hawaiian TEPs held by Lyon Arboretum and understanding the genetic representation within those collections (with Dr. Theresa Culley’s lab at University of Cincinnati). They have enlisted eleven institutions as collaborating institutions to developing research questions and protocols for conserving their own TEPs, as well as various consulting experts (Dr. Chris Walters of NGLRP, Dr. Hugh Pritchard of Kew, Dr. Kingsley Dixon of Curtain University [Australia], the University of Cincinnati, and retired USDA staffer Dr. Barbara Reed). These collaborations form the basis of the Exceptional Plant Conservation Network (EPCN) to facilitate these projects and increase resources for all interested in working with TEPs.

The diversity of species being studied in the project is impressive: rare plants from the Pacific islands of New Caledonia and Palau, Colorado, Florida, and the northeastern U.S.; ferns, orchids and tree embryos; plants from deserts to swamps, mountains to prairies. The diversity has also meant that there is great variety in the approaches needed to work with them. For instance, the CREW staff working with the Hawaii species have met a few challenges when dealing with the variety in which the tissues grow and how they respond in culture to the different hormones. Postdoctoral researcher Megan Philpott, Ph.D., has taken the challenges in stride, stating: “It can be difficult to develop protocols for so many species at one time when there is very little information available about them but it’s been a fun challenge and we’re learning a lot about the responses of tropical species to cryopreservation.”

And everything they are learning is being shared with the larger EPCN – and vice versa. Members of this larger group, from the collaborating institutions from across the country (Atlanta Botanical Garden, Chicago Botanic Garden, Denver Botanic Garden, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Henry Doorly Zoo, Longwood Gardens, Missouri Botanical Garden, San Diego Zoo Global, and the Huntington Gardens), as well as some of the consulting collaborators came together last October. At the meeting, the collaborating institutions presented the research projects they are conducting with the IMLS grant seed money. The group will reconvene and share their progress within the year. And though the IMLS grant wraps up in 2020, the connections between these far flung collaborators and their work help to better understand what it takes to conserve exceptional species will continue.

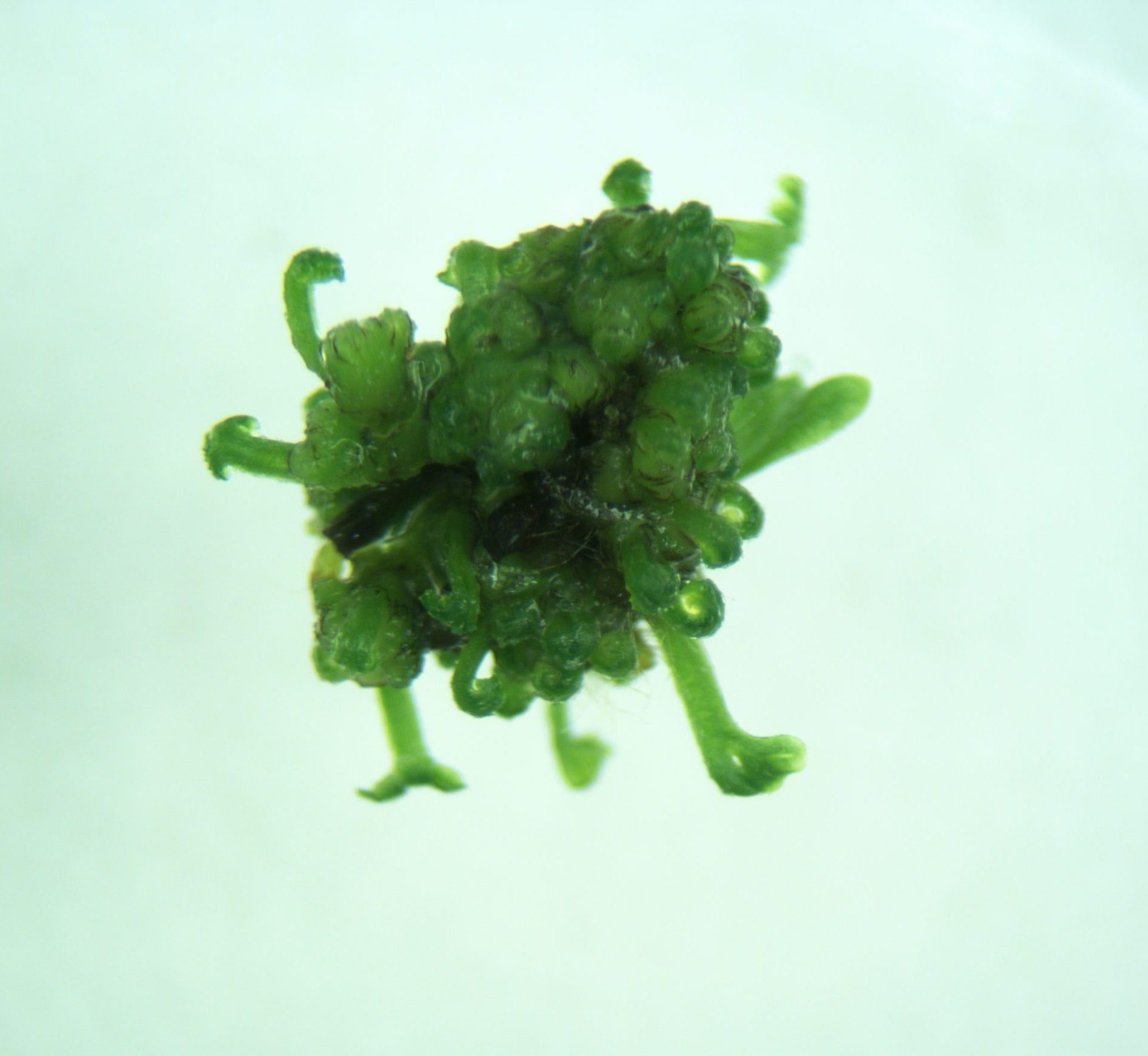

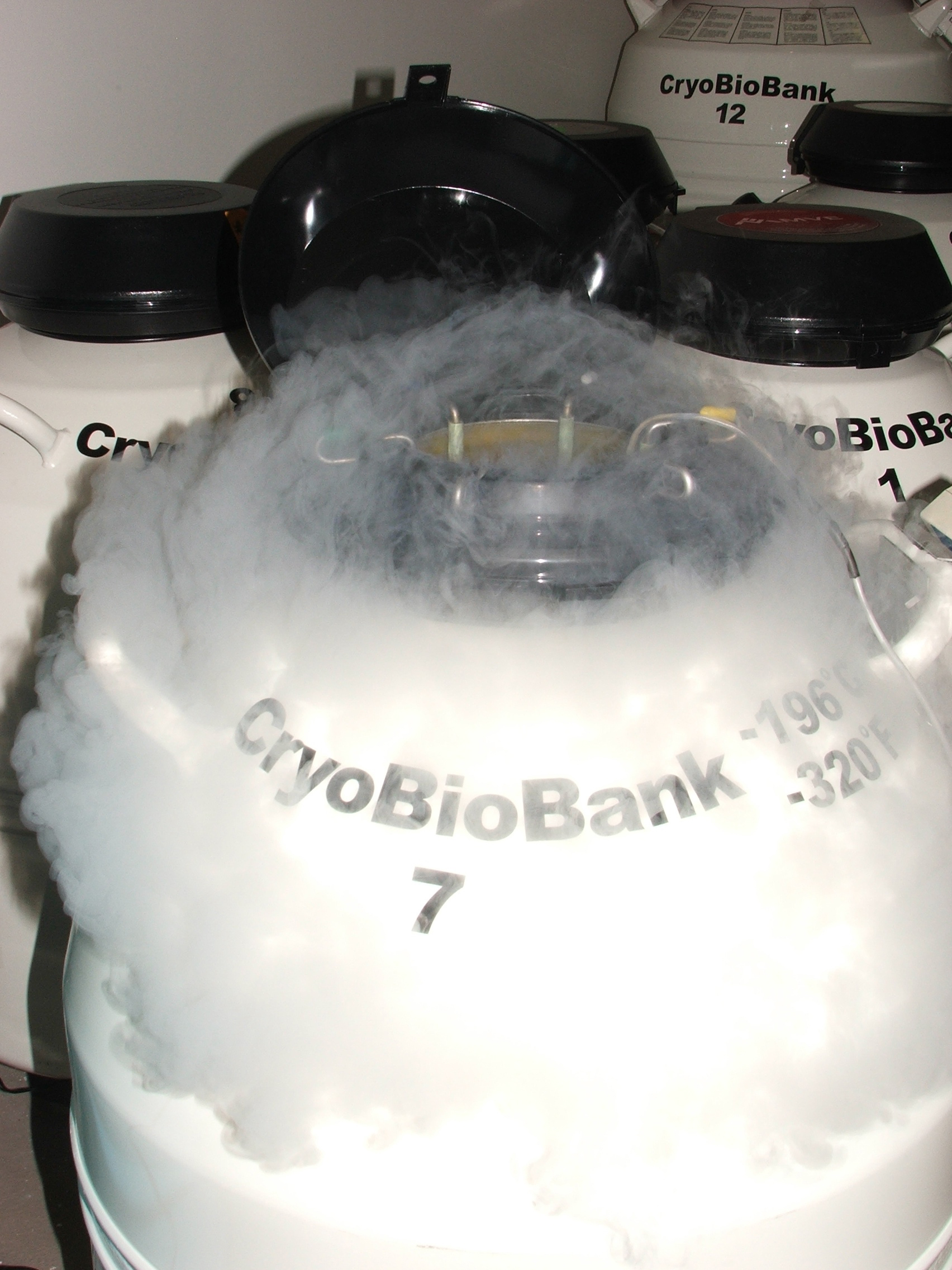

One of the many Hawaiian species CREW is working with is Asplenium peruvianum var. insulare, a federally endangered fern found on Maui and the island of Hawaii. Using the specimens of the fern kept in the sporophyte stage of its life cycle in vitro at Lyon Arboretum, CREW needed a game plan to cryopreserve it. Taking a page from their cryopreservation protocol for the endangered mainland fern Asplenium scolopendrium (American hart’s-tongue fern), CREW staff was able to produce green globular bodies (GGB), small clumps of tissue with multiple meristematic (cell dividing) regions, using media supplemented with plant growth regulators. After directly cryopreserving the GGBs using droplet vitrification, the team found an amazing 90% survival after exposure to liquid nitrogen! In addition, using GGBs has improved the efficiency of the cryopreservation process for this species, so it can more quickly and easily get many genotypes of the species into CREW’s CryoBioBank®.

Photos Courtesy of Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden.