Entangled by Rocky Mountain Fungi

Mycological and botanical research at Denver Botanic Gardens mirror each other and both will be moving into a new facility soon. The new Freyer-Newman Center at the Gardens will highlight these natural history collections as part of the institution’s effort to promote science, art, and education. The link between plants and fungi is widely recognized now at the Gardens and beyond. “Now we know that plants are absolutely dependent” on fungi, says Vera Evenson, Curator Emeritus the Sam Mitchel Herbarium of Fungi at Denver Botanic Gardens. Fungi form intimate contact with their food source and they often have special relationships with plants. Some fungi are mutualistic symbionts in a two-way beneficial relationship with a plant, while others are parasites. Other fungi are saprobes, recyclers of the natural world that decompose the tough material of a forest and make it available once again for plant uptake. In short, without fungi, there would be no plants as we know them. And we all know that without plants, there would be no animals – including us!

Yet public perception of fungi is limited. They think about edible mushrooms (or possibly fungal infections they’d rather avoid), if they think of fungi at all. But mushrooms are just the fruiting bodies of much larger fungal organisms. The vegetative part of a fungus, called the mycelium, consists of a network of fine filaments that crisscross soil or a host organism. The combination of this fascinating (and important) network with intriguing fruiting bodies has enticed many a naturalist into learning more about fungi.

Vera found herself caught up by fungi back in the 1980s. On a camping trip, her children returned from a nature exploration with armfuls of colorful mushrooms they had collected. Feeding off their curiosity, Vera promised to tap into her experience with fungi from her Master’s degree in microbiology. A lack of resources left her initial efforts to identify these large fungi fruitless, however. She turned to Denver Botanic Gardens, where she encountered one of the largest macrofungi collections of the Rocky Mountains. There she met Dr. Sam Mitchel, a medical doctor with a fascination for fungi that began decades earlier while hiking through Colorado. His collections formed the foundation of a future fungi herbarium at the Gardens: the Sam Mitchel Herbarium of Fungi.

The meeting with Dr. Mitchel had a profound effect on Vera, leading her to years of volunteering, joining the Garden’s staff, and eventually becoming curator of the fungi herbarium. Vera has worked to not only collect and care for the collection, but also to share her knowledge of and passion for fungi. She and her colleagues at the Gardens and the Colorado Mycological Society (CMS) have conducted many outreach events to entice more people to learn about the fascinating world of fungi.

Vera finds a ready audience. “The public is interested!” she exclaims, “and not just in eating them.” Recently there has been an uptick of interest in the many uses of fungi – as medicines, decomposers, and even a source material for roof shingles and more. The Annual Mushroom Fair, hosted by the CMS in collaboration with the Gardens, draws more than 2,000 people each year to be amazed by the specimens and educational displays. For Vera, it’s fun to see and hear people learn there is more to mushrooms than the foods they are familiar with, keeping an ear out for the surprised “Is that a mushroom?!”

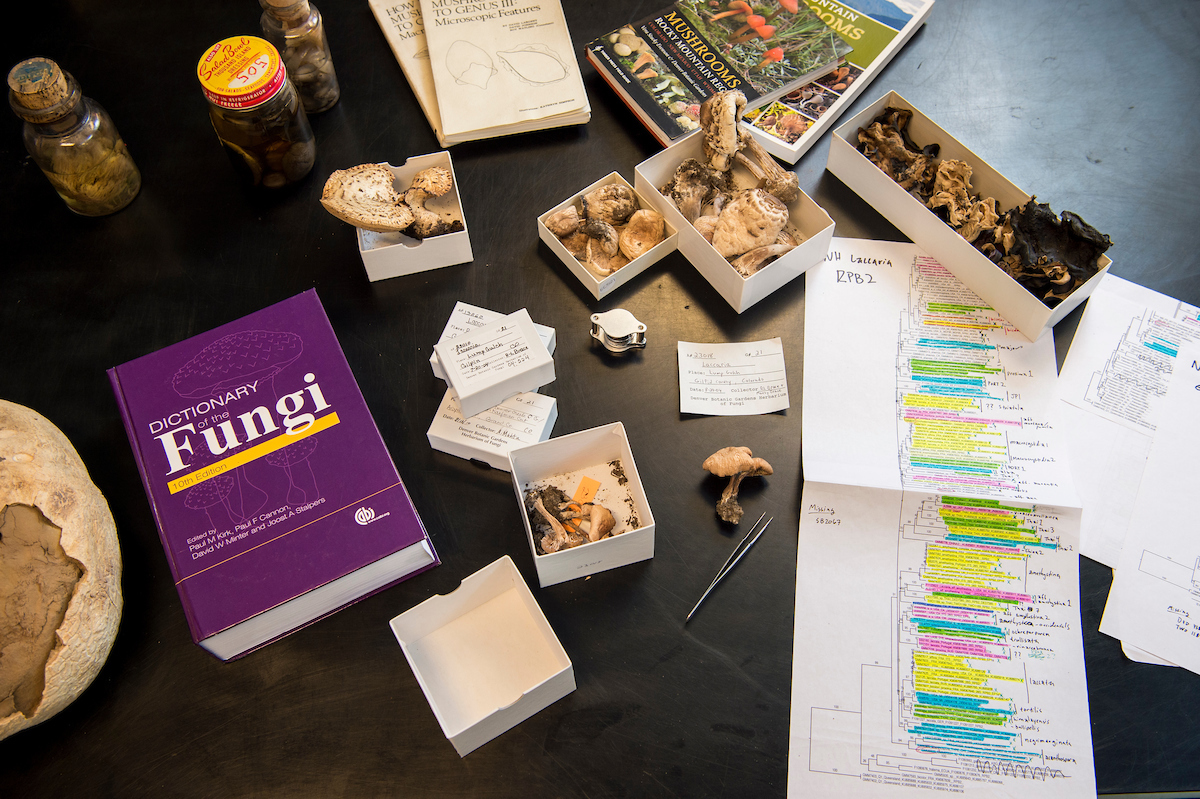

The collection at the Sam Mitchel Herbarium of Fungi contains more than mushrooms. The Gardens focuses on documenting the diversity of all macrofungi – species that generate large and visible spore-producing structures, such as mushrooms, puffballs, coral fungi, and cup fungi – in Colorado and beyond. These collections, mostly from montane forests, vary from the famously edible morels, porcinis, and chanterelles to huge fairy rings of giant puffballs. Sharp-eyed collectors have spotted tiny and colorful rare cup fungi in bogs and fens, or huge, often bitter-flavored woody polypores (conchs) growing high on the side of trees. Now housing nearly 30,000 unique specimens from Colorado and the rest of the Rocky Mountains, the collection is an invaluable regional resource.

Many years ago, Vera found herself having to defend the collection’s place at the Gardens. The fit of fungi at the Gardens was not obvious to everyone; ideas to dismantle or donate the collection floated around. It helped to have a mycologist from the New York Botanical Garden assess the collection and argue the importance of it remaining intact as a regional resource. And a resource it certainly is. Collections continue to be made as herbarium staff and other researchers strive to document the diversity of macrofungi for the Colorado Mycoflora Project (part of a greater North American effort). By identifying the species of the southern Rockies and North America, researchers can create identification guides with which the public can learn more about these organisms. A comprehensive census of macrofungi allows researchers to begin to understand their importance biologically: how species are distributed, what ecological influences dictate species distributions, and how fungal interactions benefit biological communities. For all of this, the herbarium provides a valuable reference.

The collections are used to study taxonomy and generate DNA sequence data. DNA sequencing has been a game changer for mycological studies. Attempts to document the diversity of these, sometimes cryptic, species can be quite challenging. Traditionally, mycologists do a sort of triage by assigning species names and epithets taken from species that are not necessarily local. For example, if a local mushroom seems to match the description and image of a species in a European guide, mycologists will likely apply the European species name to the local fungus. This approach can easily lead to mistaken identities. DNA sequence data, on the other hand, is not subjective. Andrew Wilson, Ph.D., Assistant Curator of Mycology, explains, “As a result, mycologists such as myself have come to rely on DNA sequence data to inform our interpretations of mushroom species and see if the morphological descriptions and categories we’re using are actually correct.”

You can learn more about fungi in Colorado and neighboring states in the book Mushrooms of the Rocky Mountain Region, by Vera Evenson and Denver Botanic Garden.

All Photos: Scott Dressel-Martin, courtesy of Denver Botanic Gardens.