Conserving Puerto Rico’s Rarest Ferns

What do ferns and Puerto Rico have in common? They are both frequently left out of U.S. plant conservation efforts! Ferns are frequently overlooked because they are not very showy and do not produce flowers or seeds. While no one can accuse Puerto Rico—with its gorgeous beaches and mountains—of not being showy, the lack of statehood and physical distance from the mainland often make it an afterthought for U.S. conservation efforts and funding.

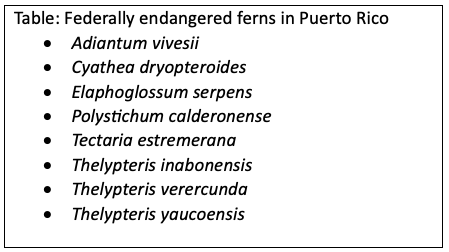

As a long-time (23 years!) biologist at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Miami, it has been a privilege and a joy to work with a tiny percentage of Puerto Rico’s amazing fern flora. For this most fun facet of my career, I owe thanks to a chance meeting in 2012 between Fairchild’s then-Conservation Ecologist Dr. Joyce Maschinski and USFWS Recovery Biologist Omar Monsegur. When Joyce and Omar met at an IUCN cactus Red Listing workshop in 2012, they began to hatch plans for what turned out to be a long-term and fruitful collaboration to safeguard several of the island’s rarest plants. In 2014, Joyce, Omar, other collaborators and I began work with four federally listed species found in the Sierra Bermeja region, as well as eight federally endangered fern species (see Table) in the western portion of Puerto Rico’s Cordillera Central. With our many partners, including the CPC, I am proud to carry on this work today.

Working with Puerto Rico’s eight listed fern species has not been without challenges! Most of the species are difficult to identify, having key characters that overlap those of similar species. In fact, the majority of these ferns pose challenges to our concept of a species: some may be sterile hybrids (Adiantum vivesii, Tectaria estremerana), and others differ only slightly from closely related, much more common species (Thelypteris verecunda, Thelypteris yaucoensis). Additionally, many of these ferns had or have occurrences that were destroyed, poorly documented location information, and/or remote, hard-to-reach locations (Thelypteris inabonensis, which we have not yet managed to survey).

We have made inroads with most of the eight fern species—albeit some more than others. Fairchild has a small but healthy ex situ collection of Cyathea dryopteroides from just one of several known occurrences. Puerto Rico Department of Natural & Environmental Resources (DNER) biologist Jose Sustache has located several additional and previously unknown populations of C. dryopteroides. Excitingly, Sustache also rediscovered not one but two occurrences of Elaphoglossum serpens, a unique and pretty fern that was thought to potentially be extinct, having not been seen in several decades. For our part here at Fairchild, by far the most progress has been made with Polystichum calderonense, the Guilarte Holly Fern.

Polystichum calderonense is a medium-sized terrestrial fern endemic to the municipalities of Adjuntas and Peñuelas in Puerto Rico’s karst belt. Although P. calderonense has been reported in a few locations within Guilarte State Forest and on nearby private property, the only plants that have been observed in the past decade are at the type locality in the Guilarte Forest.

Over the span of nine years, we have helped local biologists to document the decline of this already tiny population, from 15 plants in 2014 to 7 in 2023. The reasons for the decline were primarily natural phenomena, though one could argue that these were exacerbated by human-caused climate change. A fire—likely caused by lightning—killed some of the ferns in 2014, and damage from Hurricane Maria is suspected to have caused almost half of the population to perish in 2017. But humans may have directly caused negative impacts as well, as the site is popular for hiking and as a selfie spot.

Fortunately, there has been quite a bit of good news to offset the challenges. Propagation of P. calderonensehas been blessedly easy, with not one, but two methods available. Mature plants produce copious spores which germinate well (approximately 75% success in testing in Fairchild’s seed lab). It takes approximately 2 years from the time of spore-sowing to generate plants that are appropriately sized for reintroduction (i.e., quart-sized pots). Mature plants also produce proliferous buds at the tips of their fronds. These are fairly easy to propagate (we start them in sphagnum moss) and are a quicker way to grow a plant that is of planting size, since it bypasses the gametophyte stage.

In 2021, after several years of planning, we began a series of small pilot plantings throughout the species’ natural range. We introduced 21 plants to 4 locations but provided no aftercare, due to access difficulties. We did, however, take an experimental approach, selecting a variety of different soil types and logging temperature and humidity data at each outplanting location. Happily, one year later, we found 15 plants had survived—not bad for no aftercare!

In 2023, we tried another outplanting method, but the jury is still out as to whether it worked. We added nursery-collected spores to hydrated peat balls and pushed them into cracks in limestone. This method is very easy to do, does not require care and transport of live plants, and does not require us to locate a space where we can dig deep enough to plant a fern’s roots. Ask us in 2026 if we had any success!

Today, we have hundreds of P. calderonense in cultivation at Fairchild that can be used for reintroductions in Puerto Rico. Through the pilot plantings, as well as through ex situ cultivation, we have learned quite a bit about the species’ microhabitat needs. The ferns perform best in relatively dry peat/humus substrate, and they prefer high humidity and partial shade. In the next few years—together with our Puerto Rican partners—we hope to reintroduce dozens of plants back to the Guilarte Forest and nearby protected areas.

Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden and the USFWS have been just two of several enthusiastic partners working toward recovery of federally listed ferns and species in the Sierra Bermeja region. Other agencies critical to the efforts include the DNER, University of Puerto Rico at Mayaguez, University of Florida, Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden’s Lindner Center for Research on Endangered Wildlife (CREW), and Para La Naturaleza. We thank our friends at these agencies as well as several private citizens for their collaboration.

-

View from Pico Rodadero, where we searched for but did not relocate one of the listed fern populations. Photo credit: Jennifer Possley. -

Polystichum propagated by Fairchild tropical Botanic Garden. Photo courtesy of Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden. -

On top of the world (Monte Guilarte) in 2022 with Octavio, Coralys, Lindsey and Jennifer. Photo courtesy of Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden.