Conservation Horticulture and Parental Controls

Based on an interview with Mike DeMotta

Over 200 types of rare plants in Hawai’i are thought to have fewer than 50 individuals remaining in the wild. For many of these plants, ex situ conservation may be key to both learning more about the plants and growing more to spark their revival — or at the very least, to prevent their extinction. The National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) is one of the institutions in Hawai’i that helps these and the many other rare plants of the state. Yet maintaining such rare species in their gardens and nurseries, when only a limited number of wild plants can contribute to their genetic pool, presents unique challenges and decision making for the horticulturalists who care for the plants.

Bringing a species into the garden may offer a chance to boost breeding in that species. In Hawai’i, many species have lost their pollinators and become fragmented, remaining in only small, isolated populations. The federally endangered ‘awiwi (Kadua cookiana) is one such species, currently having only two populations. The ‘awiwi is also suffering from low production of strong pollen. By taking cuttings (genetic clones) of the wild plants and hand pollinating the mature plants, NTBG horticulturalists are able to generate more seed than can be collected in the wild. This process allows them to control both mother and father plants and mix the two populations, resulting in seed for both long-term conservation and additional conservation efforts. Another federally endangered plant, the culturally important uhiuhi (Mezoneuron kavaiensis), struggles from low recruitment in the wild but has found some breeding successes on NTBG grounds. The garden is a great place to grow uhiuhi and develop plant material to enhance wild populations as there is nothing for the plants to hybridize with!

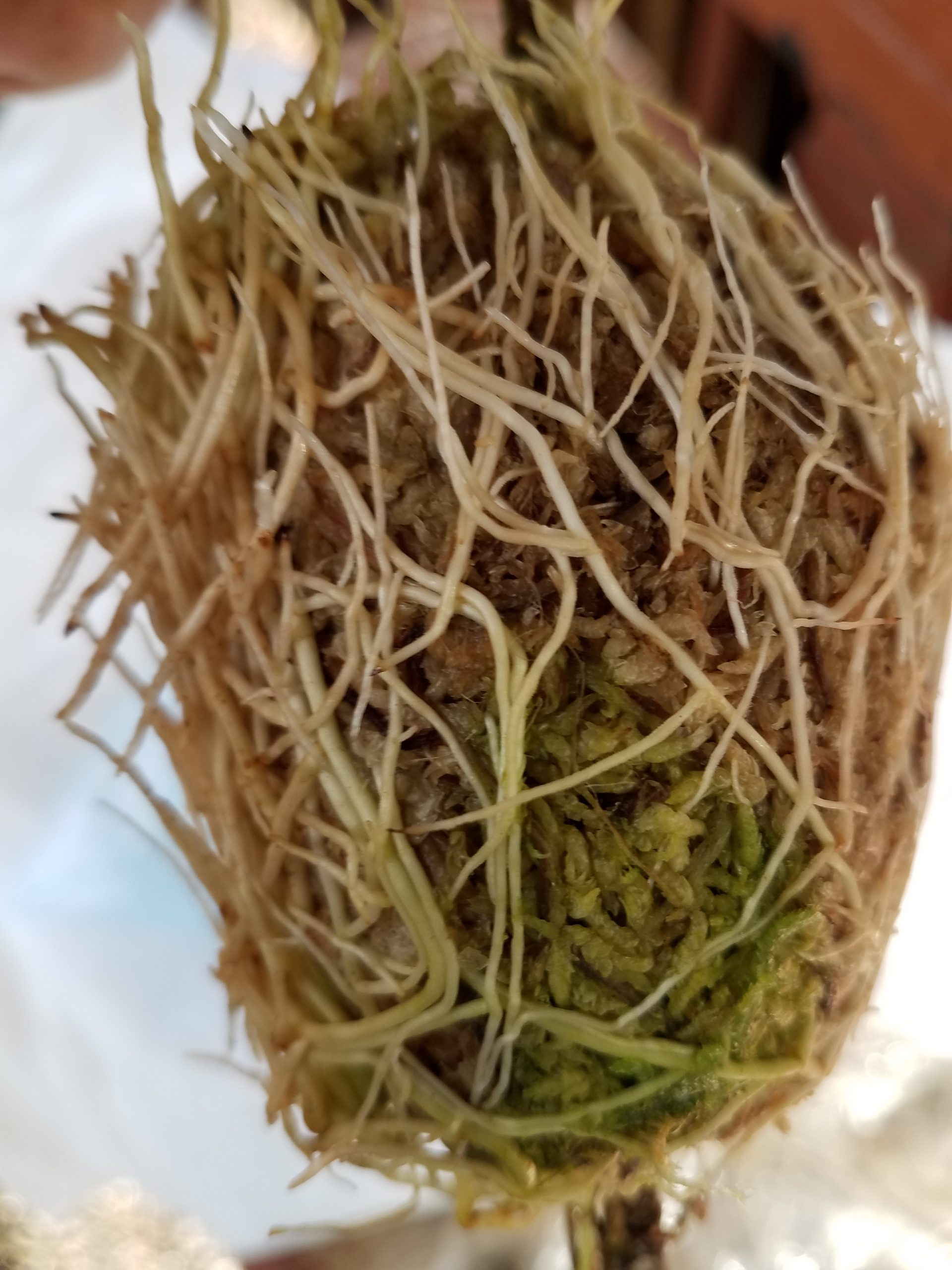

The experienced horticulturalists at NTBG are increasingly using their expertise to bring species into conservation collections. Air layering is a method of propagating new trees or shrubs from stems still attached to the parent plant. The stem is treated and wrapped in moist medium in a manner that promotes root growth from the stem, then eventually the newly rooted branch can be cut from the parent plant as a new clone. After demonstrating air layering on a specimen already held in an NTBG garden, their team received approval from the Hawaiian Department of Forestry and Wildlife to use this method to create a conservation collection of māhoe (Alectryon macroccus var. macrococcus). Air layering has proven to be quite useful in securing māhoe, as it has been difficult to obtain seed from the plant – the seeds have a tasty component which once fed humans and now attracts rats, and bagging the fruits to secure them is rarely an option due to twig borer infestations weakening the many small supporting branches. By hiking or helicoptering out to the few sites with māhoe on Kaua’i to set air layers, NTBG botanists don’t need to guess the timing of seed ripening or try to beat the herbivores – they can simply return in 3-4 months when roots have established and take their newly propagated plants with them.

Once at the garden, the air-layered clones of their wild parents are used to produce seed for long-term conservation and research. Unlike seeds collected from wild plants, the horticulturalists can hand pollinate to control the identities of both mother and father plants. With numbers of wild plants declining from around 500 to under 300 in the last 25 years, it is critical to capture as much genetic diversity from the wild populations as possible — and this horticultural technique has been the perfect tool to do so.

When horticulturalists breed plants — especially rare plants — record keeping is key. To better track parentage of plants at the garden, NTBG has made some changes to its living collections database. The placement of the parent information for the first generation of cultivated plants (known as F1 plants) is moved to a more prominent place in the database, and hot links help the horticulturalists track down the information they need to make decisions about the next generation of plants or evaluate their restoration potential. Not only are maternal plants recorded, but the pollen donor (paternal plant) is also noted when an individual is hand-pollinated. Such record-keeping will help the team maintain diversity through many generations.

At NTBG, horticultural techniques and the tools to record breeding efforts are part of their conservation tool box and demonstrate the importance of conservation horticulture for rare plants. With so many Hawaiian plants under threat of extinction —and hundreds already at critically low population numbers — conservation horticulture will continue to play a key role to help these wonderfully unique species survive. Yet survival is insufficient. The horticulture staff works with the hopes that the threats to Hawai’i’s flora can be reversed, allowing the plants to return to their important roles in the natural ecosystem.

-

Once widespread on the leeward side of the all Hawaiian islands, mahoe (Alectryon macrococcus var. macrococcus) has only a few hundred individuals remaining in the wild. Besides loss of habitat and competition from invasive plants, the species lacks recruitment as rodents are drawn to its seed and it is plagued by the black twig borer. -

The horticultural technique of air layering, promotes the growth of roots from a treatment on a branch that does not make contact with the soil. Instead, soil or moss is wrapped around the treated area. Here, a nana (Gardenia remyi) was successfully propagated from an air layer generating lots of roots. photo by Mike DeMotta, NTBG. -

The difficult terrain of many of the natural areas supporting rare plants prompts the use of helicopters to aid conservation work. Helicopter dropoff and hours of hiking were required to reach some of the remaining populations of mahoe (Alectryon macrococcus var. macrococcus). The difficulty of getting to seed in a timely manner (before rodents!) and inability to bag flowers makes airlayering a great option for brining this species into a conservation collection. photo by Mike DeMotta.