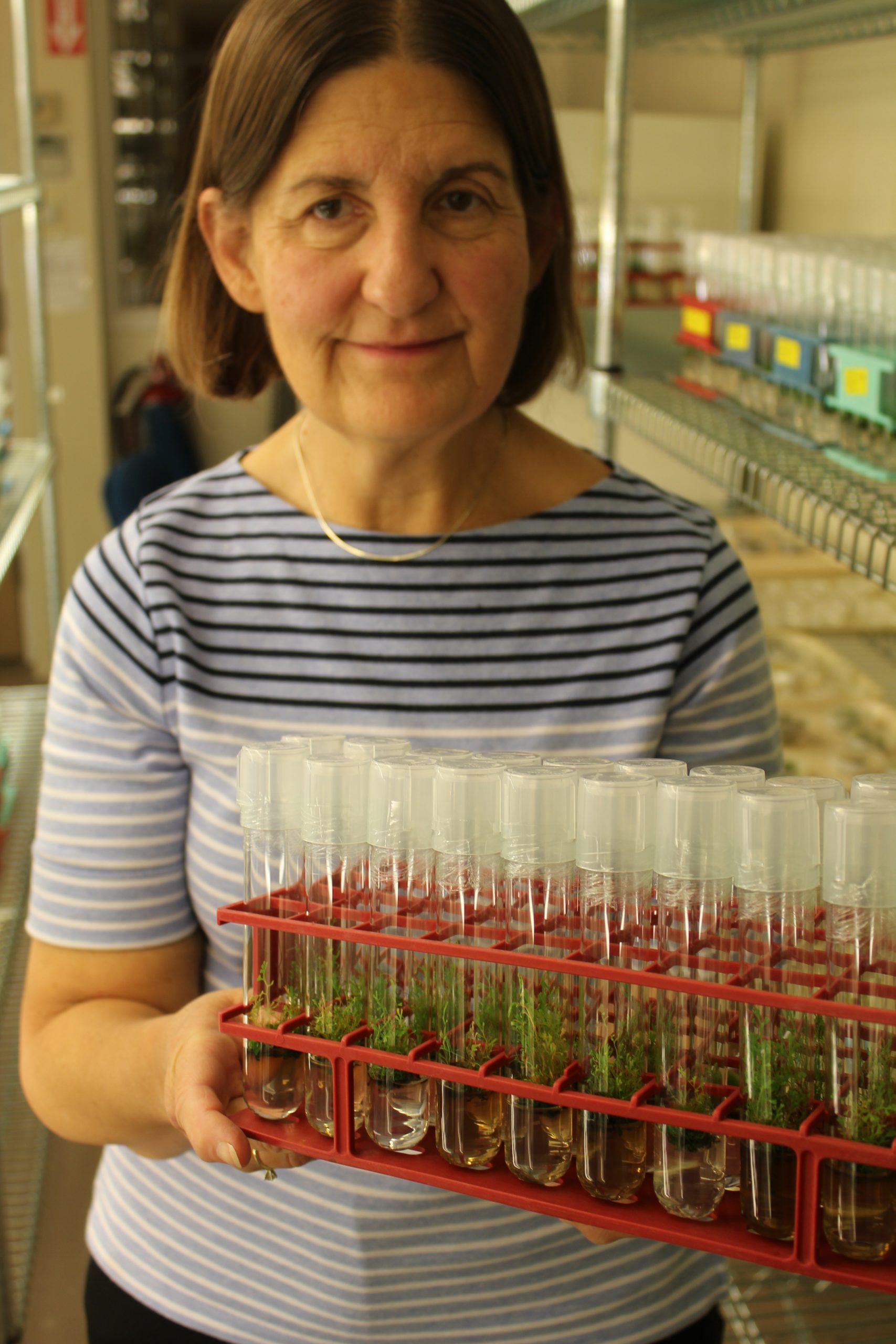

Valerie Pence, Ph.D.,

Brought into conservation through her interest in tissue culture, cryopreservation, and plant developmental systems, Dr. Valerie Pence and her Exceptional Plant program at Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden’s Center for Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife have been vital to saving rare plants unsuited to seed banking. Many CPC participating institutions – and their National Collection species – have benefited from Valerie’s work, as collaborators and in building on her pioneering work.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I first became interested in plants in college. I grew up in a very urban neighborhood and disliked my high school biology class. While retaking biology my first semester in college, I wound up fascinated and wanted to learn more. Not ready to dissect animals in my second semester, I opted for botany, with the fear that it would be boring and there might be only a couple other people in the class. It was team taught by two young and enthusiastic professors, with about 50 people in the class. After that I was hooked.

What was your career path leading up to your position as Director of Plant Research at CREW?

For my Ph.D. I worked on an aspect of the crown gall disease and Agrobacterium tumefaciens, for which I had learned tissue culture methods. I realized in the end that I was more interested in the tissue culture and plant developmental systems than in crown gall itself. I was then fortunate to have two post-doc positions after grad school both dealing with in vitro systems.

Later, as a Research Associate at the University of Cincinnati working on responses of a tomato mutant in vitro, one of the herbarium professors, Vic Soukup, would walk by the lab and see me working on tissue culture. He would stop to talk and ask questions, and one day he asked if I would be interested in trying to put Trillium, a genus he as an expert on, into tissue culture. I thought that sounded interesting, and agreed to collaborate. We eventually published 3 papers on Trillium species in culture, including the rare, Trillium persistens.

Vic was a member of the Cincinnati Wild Flower Preservation Society. He asked if I would be willing to give a talk to the group on the work with Trillium. Just about that time, the Cincinnati Zoo decided that it was going to recognize its longstanding commitment to its gardens, as well as its animals, by changing its name to the Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden. In conjunction with this recognition Betsy Dresser, founder of what has become the Center for Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife (CREW), wanted to add a plant research component to CREW. With CREW focused on cryopreservation and in vitro for animals, Betsy asked the Director of Horticulture, Dave Ehrlinger if he knew anyone who might be able to develop a similar program for plants. Dave, also a member of the Wild Flower Society, had attended my talk on Trillium. He suggested me to Betsy and I’ve been here ever since.

What about working with plants has surprised you?

Given my lack of interest in them up until college, I would say that at that point I was surprised at how interesting they are. I think now I’m fascinated by the incredible diversity of plants, and in their adaptations to so many different environments.

What drew you to work with exceptional species?

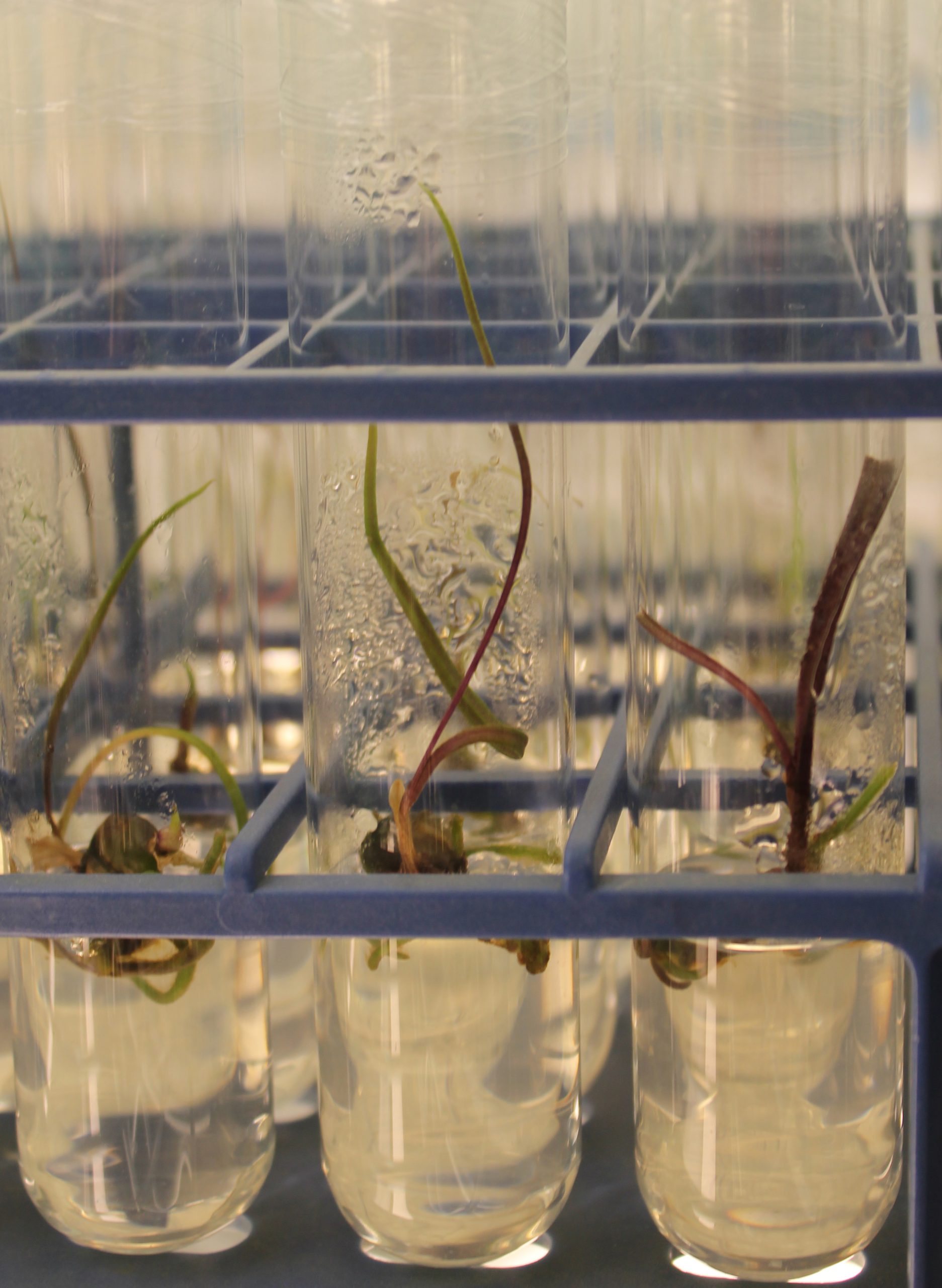

In a way, the work with exceptional plants developed in reverse. Because of my interest and training in in vitro systems and the emphasis at CREW on cryopreservation, those were the methods we focused on in the Plant Lab.

It naturally evolved that we were working with those species for which there were particular difficulties with using traditional methods for propagation or preservation—plants that were producing few or no seeds, or plants with little seed production because there were few plants, or plants with recalcitrant seeds. We were fortunate to have several grants from IMLS for developing protocols for species nominated by the CPC network, and that helped develop that area of work.

Please share one of your plant conservation projects.

The autumn buttercup restoration project has been so rewarding to be a part of because of the partners: The Arboretum at Flagstaff (TAF), The Nature Conservancy, U.S. Fish & Wildlife, and Weber State University. We’ve produced hundreds of plants through tissue culture that were acclimatized by TAF, and later outplanted on a TNC preserve in Utah. It’s been a great group to work with and a fascinating project. I’m also very excited about a project funded by our current IMLS grant, which provides seed money for in vitro or cryo research on exceptional plants in 11 other institutions, most of them CPC gardens.

What has been the most challenging aspect of your work?

Plants. The variety of plants and their responses in vitro and to cryo is challenging, it but is also the most interesting part of my work. I would like to understand more about how those responses relate to the natural adaptations of the plant. If we knew more about that, we might be able to better predict what methods would be the best for each species. A secondary challenge is educating people on the fact that plants are important and are species in their own right, as much as animals are.

Please discuss any women in science who have inspired you through your career.

I attended a women’s college, Mount Holyoke College, and the majority of professors in biology and chemistry were female. The model that women could succeed in science was accepted as normal. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve had the opportunity to meet and collaborate with some younger women scientists and have benefited from their energy and enthusiasm. And, of course, there is Dr. Emma Lucy Braun, who, in this part of the country, is an iconic figure in plant ecology, botany, and conservation, as well as a pioneer woman scientist of the early to mid-twentieth century. I first learned of her in my first year at CREW, when I met some long-time Cincinnati nature lovers. They commented that Lucy Braun would be very happy about what I was doing with plants, and I had to go look up who she was. I would never put myself in her league, but I think those of us in plant conservation are certainly trying to follow in her footsteps.