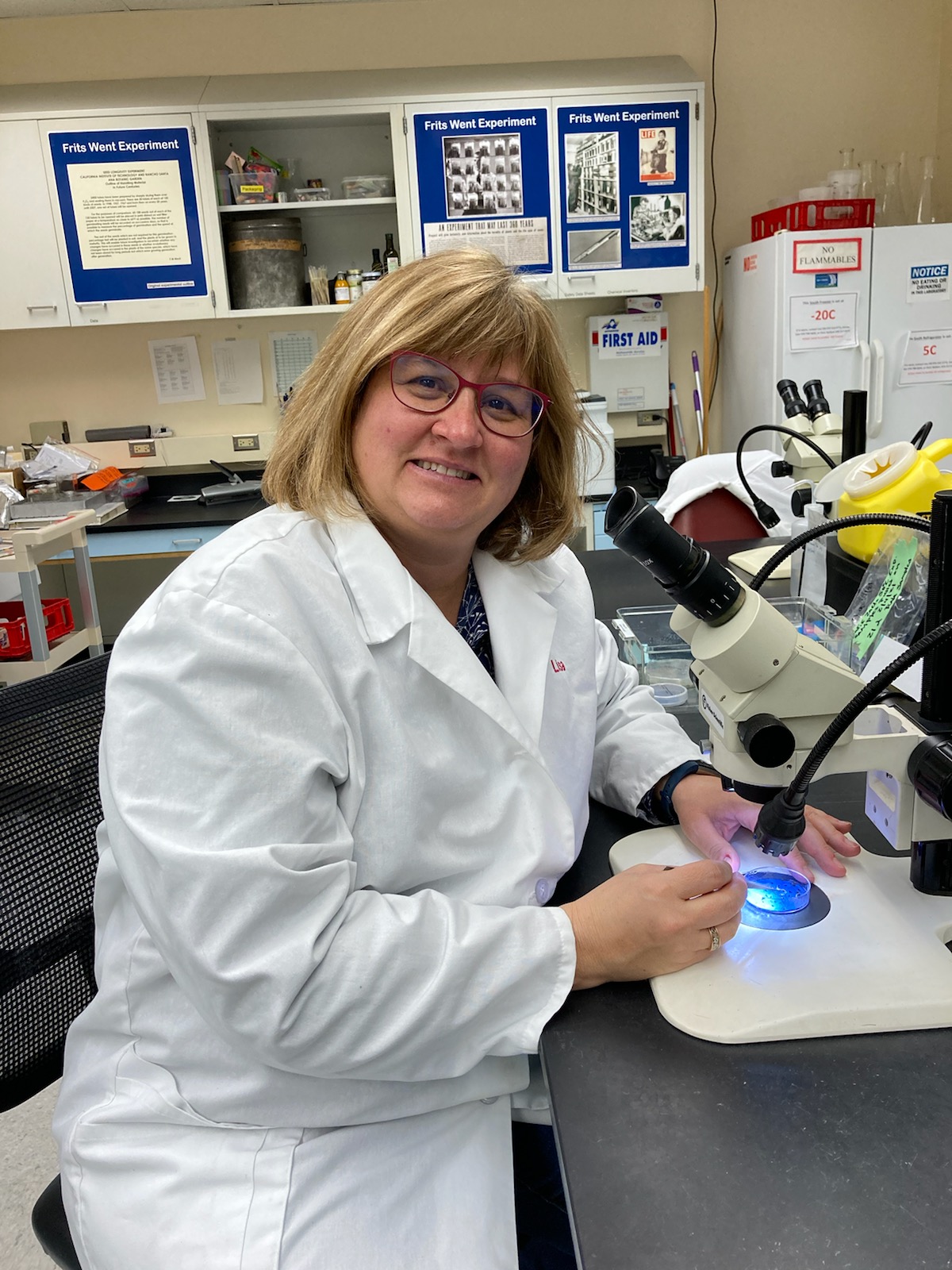

Lisa Hill

In the Biophysics Lab at the National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation, you may see Lisa Hill peering into a compound microscope, delicately extracting the embryo from an acorn. When you try this task yourself, you realize what amazing dexterity and patience is involved to accomplish this feat! Lisa’s dedication to seeds – tiny and large – has led to many important discoveries about the best way to germinate and store seeds of various species. For many years, she has been the shepherd of CPC’s rare seed collections. They could not be in better hands! We are grateful to our Conservation Champion, Lisa Hill, for her part in helping us Save Plants!

When did you first fall in love with plants?

My love of plants is still evolving. I did not grow up in an outdoorsy family. We “camped” with the neighbors at any Holiday Inn with a nice outdoor pool. My initial appreciation of plants was not in the details of a particular species, but love of a beautiful lush green landscape. I grew up in Peoria, Illinois,and visited the Pacific Northwest every summer. My most vivid memories of plants come from laying in the backseat of the car traveling to swim meets and watching the various shapes and colors of trees along the river bank or the mesmerizing, repetitive view of bright green rows of corn against black soil out the side window. My grandmother’s garden in British Columbia produced riots of raspberries and flowers and smelled so earthy. I now appreciate the diversity of plants, not just for their beauty in a landscape, but also their ability to fill so many ecosystems of our world and their complicated and diverse reproductive paths.

What was your path to joining the lab at NLGRP?

I started working at NLGRP as an undergraduate student helping a postdoctoral researcher who was investigating lipid peroxidation in seeds. It was a lab bench job, so sort of fit in with my undergraduate major in microbiology. The more interesting question is why I stayed at NLGRP. I stayed because of the people that work there. Seeing their passion and dedication to plant genetic resource preservation was inspiring and that passion rubbed off on me. We continue to hire undergraduate students. Some already have a love of plants, we hope to inspire their appreciation of seeds in all.

Why do you think it’s important to expand USDA work to more plant species?

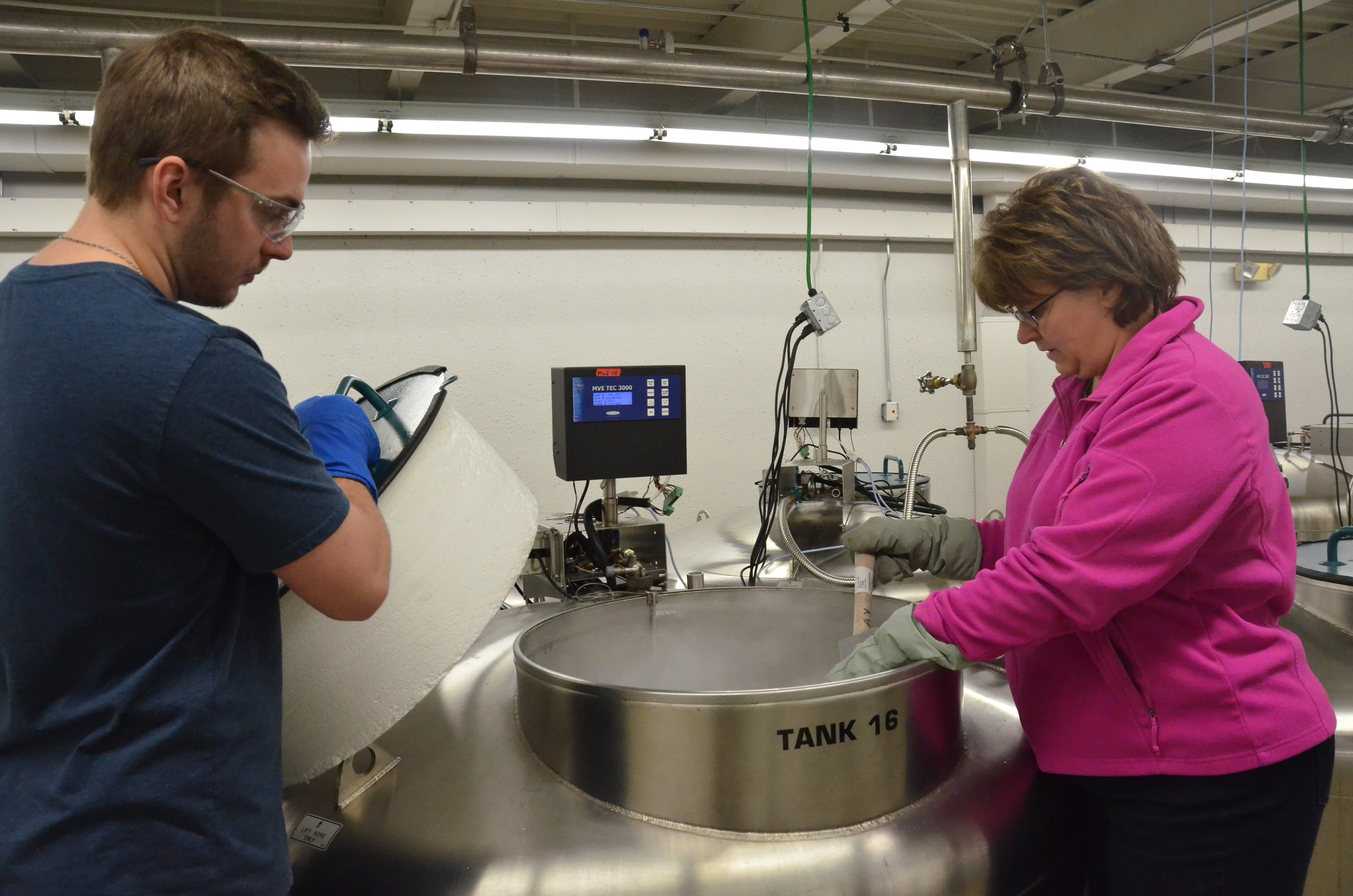

NLGRP houses 1.2 million seed accessions representing ~230 families, ~3000 genera and ~15,000 species. Our collection is vast but the taxa that go to NLGRP isn’t really our decision. Our responsibility is to ensure it’s safe while here. We carry out research on diverse plant groups to unlock the secrets of how they survive in storage and how we can revive them and grow them when it’s time to pull them out of storage.Our dedicated partners have the responsibility of ensuring that wild plants are conserved ex situ. That’s why this is a great partnership –we learn from each other and are able to leverage resources for each other.

What are the main differences in working with wild species and crop species?

Working with wild species is much more difficult than working with seeds from cultivated crop species. Seed sample size from wild species are typically small. Seed quality is less consistent. The germination requirements are often not known. Dormancy is a greater challenge to overcome. Our partners who collect and manage wild species collections often separate collections based on maternal plants, effectively making a small accession even smaller. When researching seed physiology with wild species, particularly rare or endangered species, we try to gather the most amount of information (and use non-invasive tests) from the fewest number of seeds.

-

Most of Lisa's work is agriculturally focused, as when she went to collect pollen from citrus flowers in Riverside, CA, at the USDA's National Clonal Germplasm Repository for Citrus. Photo courtesy of Lisa Hill. -

Lisa enjoyed the blooms of three red lilies (Lilium philadelphicum) at her cabin this year. Photo courtesy of Lisa Hill. -

Colorado Blue Columbine (Aquilegia coerulea) at the cabin. Photo courtesy of Lisa Hill.

What are the greatest challenges you face in your work?

My answer will sound familiar to many. The greatest challenge is that the job is big and time is limited. We are currently working on 400 guar (a type of pea), 5000 small grains, and more than 400 Seeds of Success accessions-and that’s just February! Another big challenge is accurately assessing viability when the germination requirements are unknown, not optimized, or take months to years to achieve maximum germination.

What about working with plants has surprised you?

There have been several surprises. The species level of diversity housed here at NLGRP is surprising. The number “15,000 species” can lose it’s impact in a statistic on paper. The actuality of receiving a “new to us” species every single week makes a real imprint. I have enjoyed working with a range of propagules, from seeds and fern spores to tree pollen, and with material collected in city parks, wildlife areas, and nurseries in Fort Collins. We have used that material as model systems to improve knowledge about longevity, best storage practices, and investigating seed development. I am more excited and less surprised when a really old seed germinates. I am most appreciative and encouraged by our partners that bring so much knowledge and passion to their role in plant conservation.

What excites you about up coming seed research or new applications?

We just purchased a Videometer and training starts this week! It takes multispectral images with 19 different wavelengths. At a minimum, we will use it as an auto sampler to quickly count the number of seeds for a germination assay. Our greater plan and focus will be to investigate physical properties of seeds and relate that to overall quality -and maybe even viability. This instrumentation is used commercially at seed companies, usually specializing in a few major crops. NLGRP may be the first to apply this technology to vast diversity of species. The ultimate goal is to gain more information about seed quality with out using up any of the collection.