Jennifer Possley

Working in the subtropics at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden means that Jennifer Possley has given plenty of blood and sweat to save rare plants. Her multiple talents as an observant naturalist, GIS specialist, careful scientist, brilliant photographer, not to mention her congenial personality, have made her an invaluable leader helping to preserve endangered plants in the natural areas of South Florida and the Caribbean Islands.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

It happened gradually! Growing up in Michigan on 20 acres of woods and wetland, I was always surrounded by plants, and my parents both had an affinity for plants. But that was just background to me. I majored in biology at Kalamazoo College, but I didn’t even take Botany. When I began a master’s program in Agronomy at University of Florida (UF), a love of plants started to creep up on me. By my second year, I was taking as many botany courses as my major allowed, and I really enjoyed them. Former UF botany professor Dr. Walter Judd deserves much of the credit for igniting my love of plants.

What was your path to becoming the South Florida Conservation Program Manager?

My first job after completing my master’s degree was at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Miami. I was hired as a field biologist, with six months of funding. I didn’t imagine I would stay very long. Over time, I came to adore the flora of South Florida and especially the tiny urban preserves in Miami-Dade County. I had excellent training for well over a decade, working under the guidance of Dr. Joyce Maschinski. When she left to join the CPC, I became the program manager.

What about working with plants has surprised you?

It’s been a nice surprise how many friends I have made through working with plants—locally and around the world. If you have an affinity for a plant group (like me with ferns), the other enthusiasts are a small community of instant friends whom you might visit when you travel or collaborate with on new projects. Even if you don’t speak the same language, you can at least speak botanical Latin to each other!

What are some of the threats to rare plants and challenges to plant conservation in South Florida? How have your program’s efforts met those challenges?

Well, to name a few: extreme habitat loss, sea level rise, a plethora of invasive species, inadequate funding, inadequate legal protection for rare plants, public apathy, rapid population growth, and a transient population. I think one of the things that helps us at Fairchild to meet these challenges is our staying power. We’ve had low staff turnover, good recordkeeping, and therefore good institutional memory. Our program adapts and improves over time. Also critical to our efforts has been strong, longstanding, and collaborative partnerships with land managers and biologists throughout our region. That makes our work more enjoyable as well!

Please share one of your conservation projects and how what you’ve learned could benefit others working to conserve rare plants.

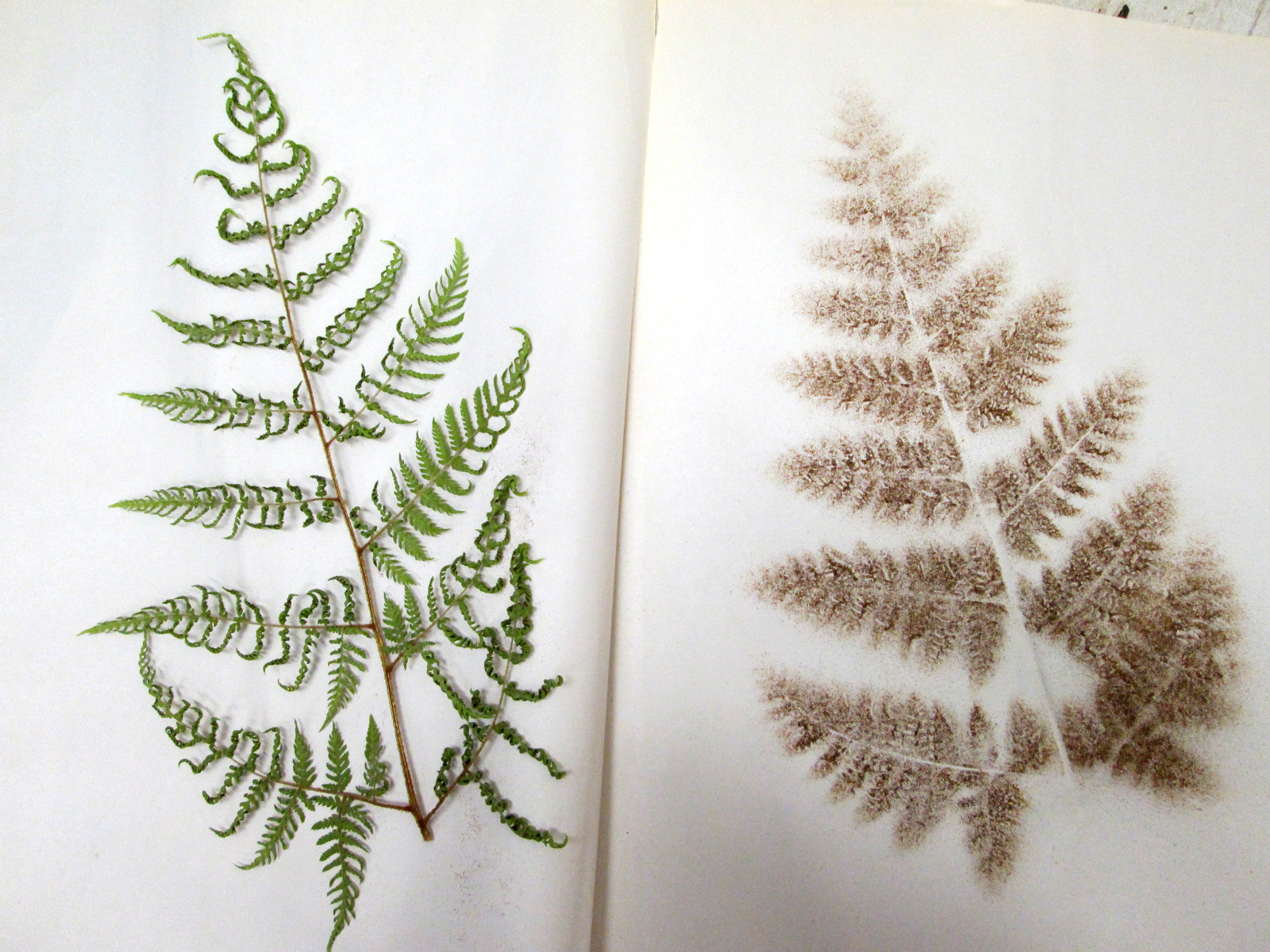

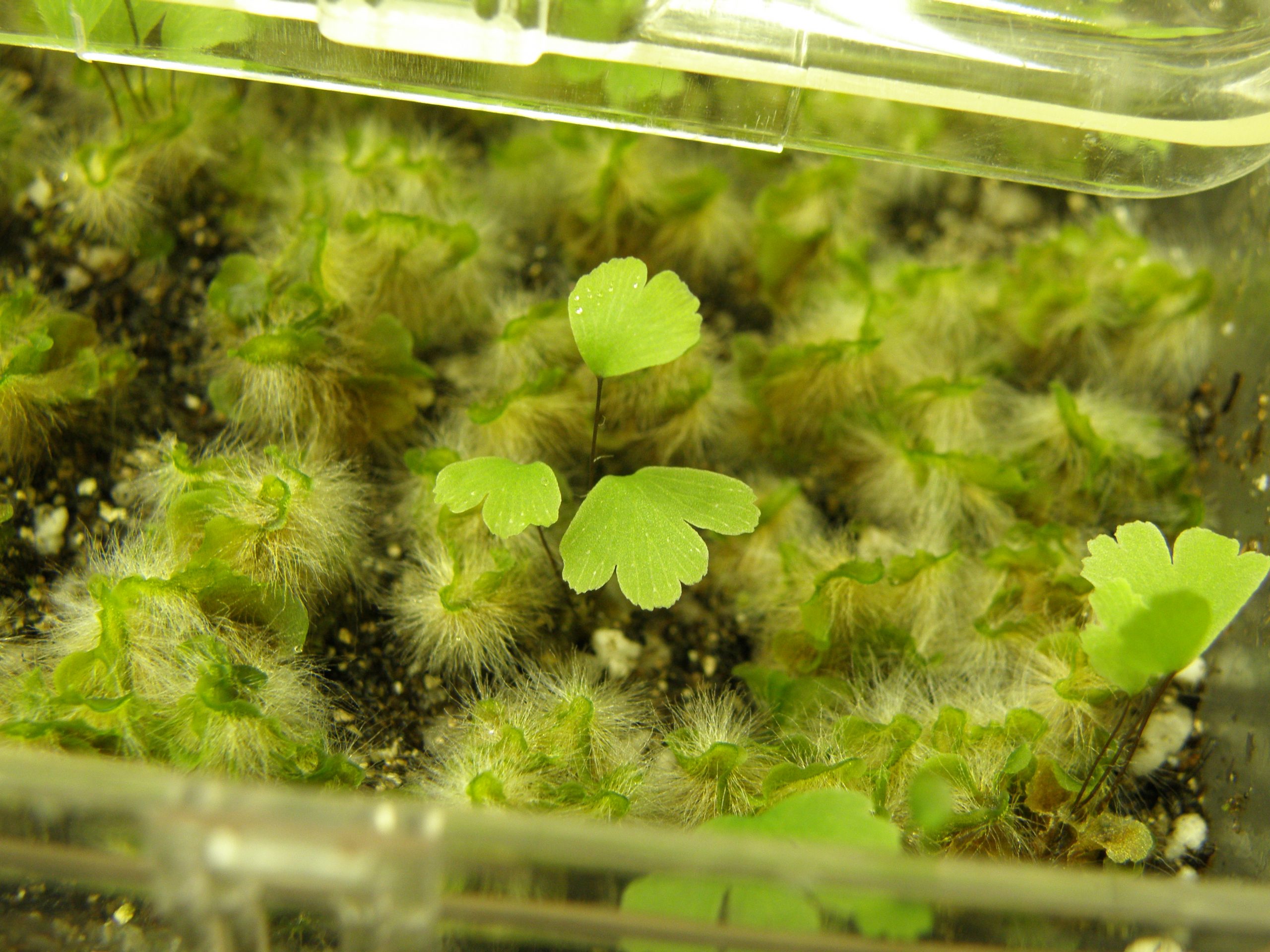

When I first arrived in South Florida, there were not very many people working to conserve the region’s ferns, despite the presence of dozens of rare fern species. Over time, and without really intending to, we built a comprehensive fern conservation program at Fairchild. We collect spores, propagate ferns from spore, and conduct augmentations and reintroductions where populations are shrinking. Guidance from colleagues within Fairchild as well as at CREW (the Center for Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife at Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Gardens) and the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation (USDA-ARS) has helped to fine-tune the program. We have a beautiful and diverse living collections of ferns of South Florida and the Caribbean, which I love to show off to visitors. More than perhaps any other types of plants, ferns may look drastically distinct during different parts of their life cycle. Even young sporophytes may look quite different from mature ones. Actually, growing the ferns myself and learning to identify them at all of their life stages has really helped to inform my field work and is also one of my favorite parts of my job.

What has been the most challenging aspect of your work?

That’s a tough question, but certainly one challenge has been finding a balance between doing plant conservation work versus interpreting our work to the public. I have been a biologist at the same botanic garden for more than 18 years now, and education and outreach has become a bigger part of my job every year. But I don’t resent that aspect of my work; I think that reaching outside of our plant conservation bubble is increasingly necessary. Everyone should understand why plant conservation is important to our planet and to ourselves.

What emerging research or conservation trends for plants do you find most exciting?

I’m happy about all the ways in which smartphones make our jobs easier. So many new apps can help us to save time and be more effective. One of my team members just downloaded “HabitApp” (only available for Android so far), which we intend to use to estimate canopy cover above recently reintroduced endangered plants. I’m excited to not burn my retinas on a mirrored densiometer (hand-held tool to visually estimate canopy cover) anymore, and to have data that will be quicker to obtain and easier to repeat. I also have been getting into iNaturalist and enjoying that. I use the app to identify insects and mushrooms, and I help others out by identifying ferns.

-

Jennifer’s early forays into conservation included working in the national AmeriCorps volunteer program, 1997. -

Carter’s orchid (Basiphyllaea corallicola), a rare orchid Jennifer has monitored in South Florida, seeing it move from a few struggling individuals to two stable populations. Photo credit: Jennifer Possley, courtesy of Fairchild Botanical Garden. -

Jennifer is willing to lay all out for plants – here monitoring ferns from a precarious perch. Photo credit: Courtesy of Fairchild Botanical Garden.

-

Juveniles of the rare holly leaf fern (Lomariopsis kunzeana) are often found around holes, and not uncommonly accompanied by large spider webs. -

Ctenitis sloanei ex situ spore print. Photo credit: Courtesy of Fairchild Botanical Garden. -

Silver dollar fern (Adiantum peruvianum) puts on vegetative growth while in a growth box. Photo credit: Courtesy of Fairchild Botanical Garden.