Dr. Peter Zale

Our October Conservation Champion, Dr. Peter Zale of Longwood Gardens, channels his passion for native orchids and scientific expertise to advance orchid conservation science through innovative lab-based seed germination techniques, establishing living collections, peer-reviewed research, public education, and more. While some native orchid species may prove elusive to work with at times, Peter proves that patience and dedication can result in long-lasting, meaningful impacts that ensure these delightful plants survive for generations to come.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

During my freshman year in high school, I was assigned a leaf collection project to learn more about identifying local woody plants, how to use a dichotomous key, and preparation of herbarium specimens. The teacher had a list of rare, unusual, and difficult-to-find species that were extra credit if included in the final project. As a kid interested in collecting all types of things, this had tremendous appeal to me, and I became intensely focused on finding these rarities. My family was hugely supportive of the project and drove me near and far to collect specimens. The project was a huge success—I ended up with something like 300 out of 100 points—but I didn’t want it to end!

Afterwards, I continued to search for all the rare trees I could locate during the project, visiting every local nursery and garden possible, and started filling my mother’s yard with unusual plants. During a visit to the Holden Arboretum not long after the project ended, I picked up a flyer with a line-drawing of the large yellow lady’s slipper (Cypripedium parviflorum var. pubescens). It was nothing short of a revelation! I remember thinking “orchids grow in Ohio?!”—and from that point I was hooked. I knew I wanted to work with plants, and particularly native orchids, for life.

What was your career path to Longwood Gardens?

Working for a public garden was something that didn’t come onto my radar until grad school. I attended The Ohio State University, where I started in landscape design but quickly changed course once I started learning about the science of horticulture—seed science, plant propagation, and plant identification. Ultimately, I obtained a bachelor’s degree in horticulture science. I then had the unique opportunity to help develop and then manage a certified organic retail and wholesale nursery that focused on native plants. Through this experience, I was able to collect seeds and learn propagation protocols for a wide variety of native plants—but it left me wanting more.

I returned to graduate school, where I studied the quantitative genetic characteristics of a breeding population of Magnolia virginiana and made seed collections throughout the species’ range, with the idea of continuing genetic work on this project for my Ph.D. However, an opportunity to pursue my Ph.D through the Ornamental Plant Germplasm Center (OPGC) led me to focus on germplasm collection development, through extensive botanical field work, genetic characterization, and interspecific hybridization of the genus Phlox. During my time at OPGC, several public garden curators visited and strongly encouraged me to pursue a similar role in a public garden. The idea had never occurred to me, but ultimately it was the best professional advice I ever received. The week before I defended my dissertation, the position at Longwood opened. I started as Curator and Plant Breeder in 2015 and immediately initiated our native orchid conservation program.

What native orchid conservation initiatives are you most excited about?

I am most excited about some of the laboratory-based seed germination techniques that allow us to not only expand the role of horticulture and collections development of native orchids in a public garden setting, but also provide unique avenues for original research. This is particularly exciting because there is an often-perpetuated myth that native orchids are difficult or impossible to grow—and it is simply not true. Our work illustrates this through the establishment of living collections in the gardens and peer-reviewed research. The native orchid conservation team at Longwood has embraced a similar approach; it has been exciting to watch them expand, develop, and experiment with seed germination techniques in ways that have and will continue to help us contribute to the science of orchid conservation.

What successes or challenges have you encountered in your work?

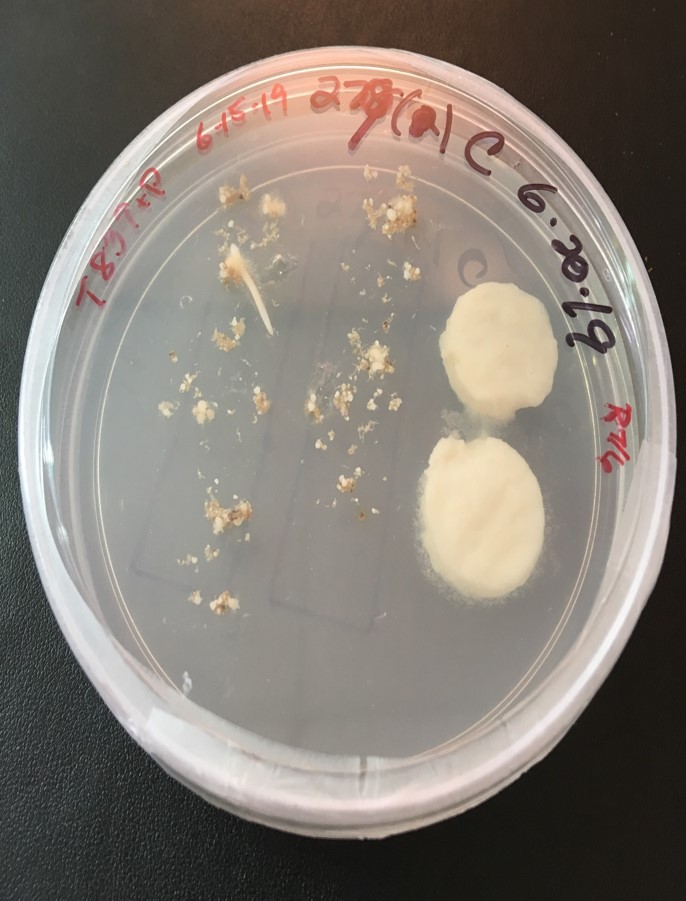

I am particularly proud that we have been able to “crack the code” for a handful of native orchid species that have been considered difficult or impossible to germinate. For example, we were able to germinate and grow seedlings of Platanthera peramoena, a state-listed species in PA that is of conservation concern throughout much of its range, which has been considered extremely difficult to germinate using mature seeds. We implemented a series of studies to determine the potential for using embryo culture work to successfully germinate this species.

Embryo culture—a well-known method for circumventing seed dormancy in mature seeds—has been tremendously successful in orchid conservation work by other institutions but requires a specific knowledge of seed maturation time and timing of seed harvest. Through meticulous hand pollination and serial harvest of seeds, we determined how to effectively and repeatably propagate this species when seeds are harvested at 26 days after pollination. We have even been able to extrapolate the technique to closely related species, with the hope that it can eventually be applied to endangered species such as P. leucophaea and P. praeclara.

Educating the public about native orchids continues to be an important area of focus for us. In early 2022, Longwood Gardens opened its new orchid house to the public. My team had the opportunity to set a display table highlighting our conservation work with native orchids. 8,000 people visited the conservatory that weekend—and it felt like we talked to just about all of them!

We were shocked to discover that probably 9 out of 10 people have no idea that orchids grow naturally in PA, let alone that at least 60 taxa of orchids have been found historically throughout the state. After learning about them, one visitor remarked, “Wow, so many orchids in Pennsylvania…who brings them all in in the winter?” Although this statement initially made us chuckle, it gets at the larger issue that most of the public only associate orchids with the tropics or houseplants, and generally have no idea that orchids can literally be found in their backyard. From that experience, it became clear to me the importance of increasing public awareness about native orchids in tandem with their need for conservation.

What has surprised you about working with and learning more about rare orchids?

The most surprising thing about native orchids is that rarity in the wild does not mean an orchid will be difficult to propagate or grow—and an orchid that is more common is not necessarily easy in the same regard. For example, Cypripedium kentuckiense is one of the rarest native orchids in the U.S., but we find it to be among the easiest to propagate and grow of all the native orchids we have worked with. Conversely, the showy orchid (Galearis spectabilis) is among the most common orchids in our region and occurs naturally on Longwood Gardens property, but it has proven to be one of the most difficult to propagate and grow! This pattern has been repeated throughout our experience with a variety of native orchids and never ceases to surprise us.

What advice would you give to those who wish to learn more about how they can help save imperiled plant species?

I would first suggest that anyone interested in plant conservation find and join a local plant conservation alliance. These organizations are spread throughout the country and are the hub that unifies scientists, horticulturists, botanists, ecologists, and anyone interested in any aspect of plant conservation. Pennsylvania has a progressive and engaged plant conservation alliance in which we are very active. It has been a tremendous boon for our orchid work and as we continue to expand our ex situ conservation and restoration efforts to other rare plants from the state.

Working with native orchids has taught me the importance of patience, dedication, and humility. Eight years into our orchid conservation program, there are days when it seems like we’re making progress, and other days when I feel like we just started! Those wishing to work in orchid conservation should understand that quick victories may be elusive. Real results often take time, but those results can be incredibly long-lasting. Our work with lady’s slipper orchids exemplifies this—with estimated generation times of 100 to 400 years, plants we are propagating, conservation collections we are building, and populations we are restoring have the potential to tell our conservation story for centuries to come.