Dr. Lucy Commander

Our September Conservation Champion, Dr. Lucy Commander, is known for her outstanding research on seed germination in arid Western Australian and the Middle East. In her capacity as Project Manager at the Australian Network for Plant Conservation, she spearheaded production of the Guidelines for Translocation of Threatened Plants in Australia and the Florabank Guidelines, as well as organized many conferences on specialized areas of plant conservation including orchid conservation and seed science. Each project and publication allows Dr. Commander to reach a broad scientific and lay public not only in Australia, but around the world. We solute Dr. Commander’s noteworthy achievements that help Save Plants.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

When I was in year 10 at school, I was in the choir and orchestra. The school got us to sell flower bulbs to fundraise for our music tour to the Kimberly region in the north of Western Australia, and my science teacher gave us all a gladioli bulb. I was fascinated watching these bulbs grow and developed an interest in gardening. I had always been interested in science at school and chose to study horticulture at University. It was in my second year that I did a botany unit called ‘Land Plant Diversity’ and really fell in love with Australian plants—they were so much more interesting than roses and carnations! Just look at the floral structure of our native plants, like the kangaroo paw (Anigozanthos manglesii) that looks like the paw of a kangaroo and is adapted to bird pollination.

We have orchids that look like donkeys (Diuris spp.); feather flowers (Verticordia spp.) named after Venus, the Turner of Hearts, because of their beauty; and trigger flowers (Stylidium spp.) named for their unique pollination mechanism, triggered when an insect lands on the flower. Also, I’m fascinated by all the adaptations that plants have to their environment—the ability to tolerate saline environments, low phosphorous soils, or places where it doesn’t rain for months at a time. I’m really lucky to live in Western Australia, a biodiversity hotspot, with some of the most interesting and beautiful plants in the world.

What are some of the pressing conservation needs related to Australia’s rare and native plants?

There are so many! Land clearing and degradation is one of the biggest threats. In addition, diseases caused by pathogens known as dieback (Phytophthora cinnamomi) and myrtle rust (Puccinia psidii) are terrible. Inappropriate fire regimes—too frequent or not frequent enough, in the wrong season, or too intense like the recent catastrophic fires—can be devastating. Grazing by non-native feral herbivores, competition from non-native invasive species, loss of beneficial biotic interactions with native fauna due to predation from introduced fauna, and changes in rainfall patterns also threaten rare plants. Some of these threats are exacerbated when combined, such as drought followed by extreme fire.

What was your career path to ANPC?

In the final year of my undergraduate degree in Horticulture, I did a fourth-year project on seed germination of a tree needed for restoration of a diamond mine in the Kimberly. Straight out of university, I worked for a research nursery helping to grow native plants for field trials. Next, I got a job working at the state’s botanic garden—Kings Park and Botanic Garden—where I helped the seed scientists with their experiments for a year as a technical assistant. Then I completed a Ph.D. project on restoration of borrow pits at a solar salt facility at Shark Bay, on the Western Australian coast.

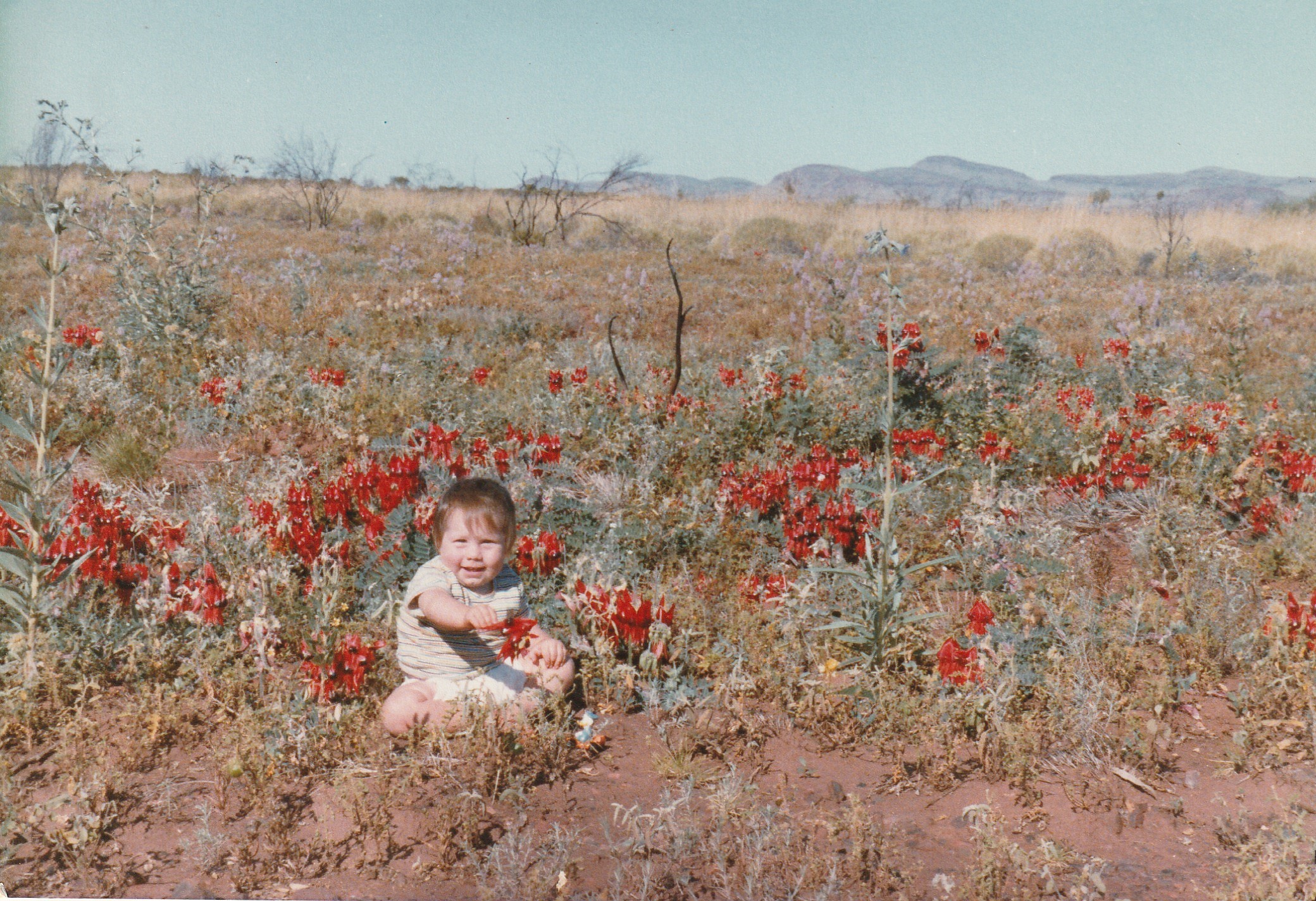

As a post-doctoral associate, I worked on various projects helping mining companies in Western Australia do better seed-based restoration. This involved travelling to mine sites in remote parts of the state. Our state is huge—2.6 million km2, or about 11 times the size of Texas, with only 2.6 million people! I worked in the Hamersley Ranges, Great Sandy Desert, and Koolanooka Threatened Ecological Community, surveying vegetation, collecting seeds, doing experiments in the laboratory on seed germination and dormancy, planting and seeding field trials, and monitoring field trials.

I also wrote scientific papers and industry reports, gave presentations, and organized conferences. I really appreciate having a solid scientific training as well as practical on-ground experience. Spending time with industry professionals as well as botanic gardens staff has given me a good understanding of different perspectives and issues.

In 2016, I started working for the Australian Network for Plant Conservation (ANPC), as Project Manager for update of the Guidelines for Translocation of Threatened Plants in Australia. I coordinated a group of 30 authors from across Australia to write and edit the third edition of the Guidelines. I also ran workshops about the Guidelines in the state capital cities of Sydney, Perth, Canberra, and Adelaide. Over the last two years, I’ve been updating the Florabank Guidelines.

What advice do you have for newcomers to the field of plant conservation?

Find what aspect of conservation you’re most passionate about—but also make sure you have a broad range of skills and knowledge, so you can adapt to new jobs and places and relate to people in different sectors. Talk to as many people as you can about their experiences. As travel is challenging at present, see if you can find out about plant conservation around the world through documentaries, webinars, and books. It’s nice to have a global perspective on issues, even when working at a local scale. And it’s interesting to learn about different species and ecosystems!

Please share more about the Florabank Guidelines project at ANPC. What are the goals and desired outcomes?

The Florabank Guidelines are best-practice guidelines for native seed collection and use. They were first published 20 years ago, and I’ve been leading a team of over 45 authors to update them. We want to share the knowledge, research, and experience that has been gained over the past 20 years to improve practices across the country.

We hope that everyone involved in native seeds will read the Guidelines—not just those involved in the seed supply chain (collection, processing, production, testing, storage, propagation, and seeding), but also those making decisions that affect the use of native seeds, such as restoration planners, policy makers, licensing staff, and funding organizations. We’ve even written a new chapter on tips for seed purchasers.

Ultimately, we hope that native seed is used more efficiently, and that restoration projects using native seeds will be more successful, leading to improved outcomes for the environment.

While these Guidelines are focused on Australian native seeds and restoration of Australian ecosystems, some of the information (such as seed storage, production, and technology) has been sourced from the international literature. Much of the information can be adapted for other countries, so we hope that global users of native seeds will find it useful.

What successes and challenges have you encountered in your work?

The fires in Australia in the summer of 2019/2020 were challenging, even though I was not directly affected. Many of the authors of Florabank Guidelines were helping with recovery efforts, and consequently we experienced delays in the writing process. Then, of course, the pandemic and resulting travel restrictions meant that in-person meetings, workshops, and conferences have been cancelled or postponed, so networking and information sharing is more challenging. But we’ve risen to the challenge, upskilling to run online webinars and posting presentations on YouTube. In some instances, I think we’ve been able to reach more people than if we’d had in-person events, but I’m still looking forward to the time when I can see colleagues on the other side of the country, as well as the other side of the world!

Ultimately, I’m really proud of the Florabank Guidelines, and also the Translocation Guidelines. The success of seeing these two guidelines through to publication shows what can be done when people work together for a common goal. The Translocation Guidelines have been referred to in state government policy, so I’m really proud that I’ve been able to make a difference at that level.

What emerging science (methods, approaches, discoveries) and/or trends in plant conservation excite you most?

I do get very excited about seed germination! I think it’s amazing when someone ‘cracks the code’ to find out how seeds know when and where to germinate in their natural habitat, and then are able to replicate that in the nursery or lab to enable ex situ propagation.

I love integrated projects where people from lots of disciplines or areas of expertise work together to solve problems. It shows how important diversity and creativity are to coming up with ideas and solutions.

What has it meant to you to be a member of the CPC network? How has CPC supported your work?

CPC has great resources on their website. Joyce Maschinski, CPC President & CEO, has been a wonderful supporter of the Translocation Guidelines and wrote a lovely Foreword. It’s nice to be part of the global plant conservation community. Working at ANPC, I certainly value the importance of networks to bring people together and share information.

What advice would you give to the public who want to learn more about how they can help save imperiled plant species?

Join an organization like CPC or ANPC. Follow them on social media or sign up for their newsletters. That way you’ll receive information and news stories to inform yourself about the positive work that’s going on and some of the threats to imperiled plants.

Join a ‘friends’ group in your local area, either at a botanic garden, a natural area like a national park, or even your local patch of remnant vegetation. You will be able to make a hands-on difference by growing plants or reducing threats like removing invasive species.

I find it quite overwhelming to consider how I, as an individual, can help save imperiled species, other than by sharing information and raising their profile. But I think that I can make a difference by making small changes in my everyday life to help reduce the threats to imperiled species. Reducing my consumption; reusing, recycling, and composting; growing some of my own food (I have a lemon tree and a small vegetable patch); providing resources for pollinators in my garden; and educating my children about threatened species can all help reduce my footprint on the planet. I guess saving plants is not just about seed banking, putting up fences and replanting–it’s also about everyone making a few small changes to their own lives to reduce the threats that these plants face.