Dr. Jessamine Finch

Our December Conservation Champion is Dr. Jessamine Finch, research botanist for the Native Plant Trust. Jessamine’s work and research at the New England Plant Conservation Program’s seed bank helps advance our understanding of rare plant conservation, and her support of community science and public education initiatives engages new stakeholders to help us reach our collective conservation goals to save endangered plants. Jessamine’s integrated and collaborative approach to rare plant conservation is a wonderful example to us all, and she reminds us that “all actions, no matter how small, help us further plant conservation.” We thank Jessamine for all she does to Save Plants!

When did you first fall in love with plants?

While I have many fond memories of spending time outdoors in my youth, I think plants and I started to “get serious” about our relationship while I was an undergraduate working and studying at the Botanic Garden of Smith College (Northampton, MA). Meeting plants in the glasshouses and across campus, I was taken by the incredible variation in form, size, and color. For many years, I wasn’t sure where this interest in plants would take me, and I explored topics like landscape design and horticulture alongside biological research.

What was your career path to Native Plant Trust?

After college, I worked for a year in horticulture before pursuing graduate studies in Plant Biology and Conservation with Chicago Botanic Garden and Northwestern University. My research focused on seed sourcing milkweeds (Asclepias) for ecological restoration, combining methods in seed ecology and population genetics. While finishing my degree, I supported and then led Budburst, a community science project investigating the effects of climate change on plants and animals. When a colleague shared an ad for the Research Botanist position at Native Plant Trust, offering leadership of the seed bank and looking for experience with genetics, I knew I had to apply. In February I will be celebrating my three-year anniversary at Native Plant Trust.

What are some of the conservation-related projects you’re currently working on?

My conservation work centers around the seed bank of the New England Plant Conservation Program (NEPCoP), which has recently surpassed 2,000 collections! Through germination trials, I assess seed viability and gain insights into the dormancy and germination of rare plants─for many of which, little to no information is available in the literature. Looking forward to January, I am excited to hire our second Petcavage Seed Conservation Intern, a newly endowed position which supports collections management and research with the seed bank.

A major project I am currently working on is the update to our regional list of rare plants in New England, Flora Conservanda (1996, 2012). Led by the Regional Advisory Committee of NEPCoP, I am working with the Director of Conservation, Michael Piantedosi, to synthesize data on plant populations (including number, size, threats, and land securement) to generate a revised list expected to be published in 2023. I have also begun working on establishing an experimental test of chaperoned managed relocation, a modified conservation technique proposed by Missouri Botanical Garden. Working with the Oak Spring Garden Foundation (Upperville, VA) and the Coastal Maine Botanic Garden (Boothbay, ME), Native Plant Trust will trial rare, dispersal-limited herbaceous perennials beyond their northern range margin to evaluate this new method.

In your experience, what are some of the pressing conservation needs impacting the rare and native plants of the United States?

To counter the negative impacts of habitat fragmentation, loss of pollinators, climate change, and other threats, plant conservation needs more money, more people, and more time. Public engagement is crucial to directing more resources to plant conservation. The more folks who understand and can speak to the value of plants, the greater the pressure on our representatives to further policy that supports biodiversity conservation.

Working within the present confines, we need to secure land conservation easements, manage invasive species, and counter other drivers of decline, while simultaneously working to safeguard genetic diversity in ex situ collections. Techniques like seed banking, cryopreservation, and tissue culture can help us preserve unique genetic diversity before it is lost forever, allowing for the recovery and reestablishment of plant populations in the future.

How can public engagement & outreach help achieve conservation goals?

Engaging the public is critical to reaching our conservation goals. Since 1993, the Plant Conservation Volunteers program has been working with community scientists across the New England region to monitor and collect seed of rare plants─and we are not the only ones! In a recent study with colleagues from Plants of Concern at Chicago Botanic Garden, we surveyed 15 different community science projects that work with volunteers across the U.S. to monitor rare plants. Opportunities like these allow us to conduct more monitoring and respond more quickly to declines, while also nurturing plant conservation ambassadors who can bring that knowledge and passion into their communities, extending our reach.

What successes or challenges have you encountered in your work?

One challenge I am grappling with is how we adjust our rare plant work to account for intracontinental plant migration, resulting in what some call “neonatives.” For example, how should we classify a new occurrence of a plant that is native to eastern North America but not considered native to New England? Labeling this occurrence as ‘non-native’ may be inappropriate, as plant migration is a natural process that is expected to increase under climate change. However, labeling it ‘native’ may be inappropriate if the occurrence is a cultivated variety and/or garden escapee. In our ongoing update of Flora Conservanda, we are proposing a conservation planning framework for consideration of newly arriving native species, based on the origin and behavior of the occurrence (e.g., persisting, recruiting, colonizing new sites) as well as the geographic range of the species.

What has surprised you about working with and learning more about rare plants?

Something that has surprised me about working with rare plants is that you can live in an area for years and never encounter a given plant species, even if you spend a lot of time outside and in natural areas. People often say that it is hard to love something you have never met. While it may not be appropriate to plant rare species in private gardens, I think it is so important for places like botanic gardens to display them to enable people to meet their local rare plants. Becoming a rare plant monitor with programs like Plant Conservation Volunteers is another great way to build relationships with the rare plants in your area.

What advice would you give to those who wish to learn more about how they can help save imperiled plant species? How can the public learn more and get involved?

Everyone has the potential to help save imperiled plants, no matter your skill set, location, or availability! Reach out to local botanic gardens, state native plant societies, land trusts, and parks to inquire about opportunities. Become a rare plant monitor. Promote plant conservation knowledge and happenings in your networks. Vote for candidates who prioritize the environment, and don’t be afraid to reach out to your representatives to voice your concerns and encourage them to support key legislation! Remember that all actions, no matter how small, help us further plant conservation.

-

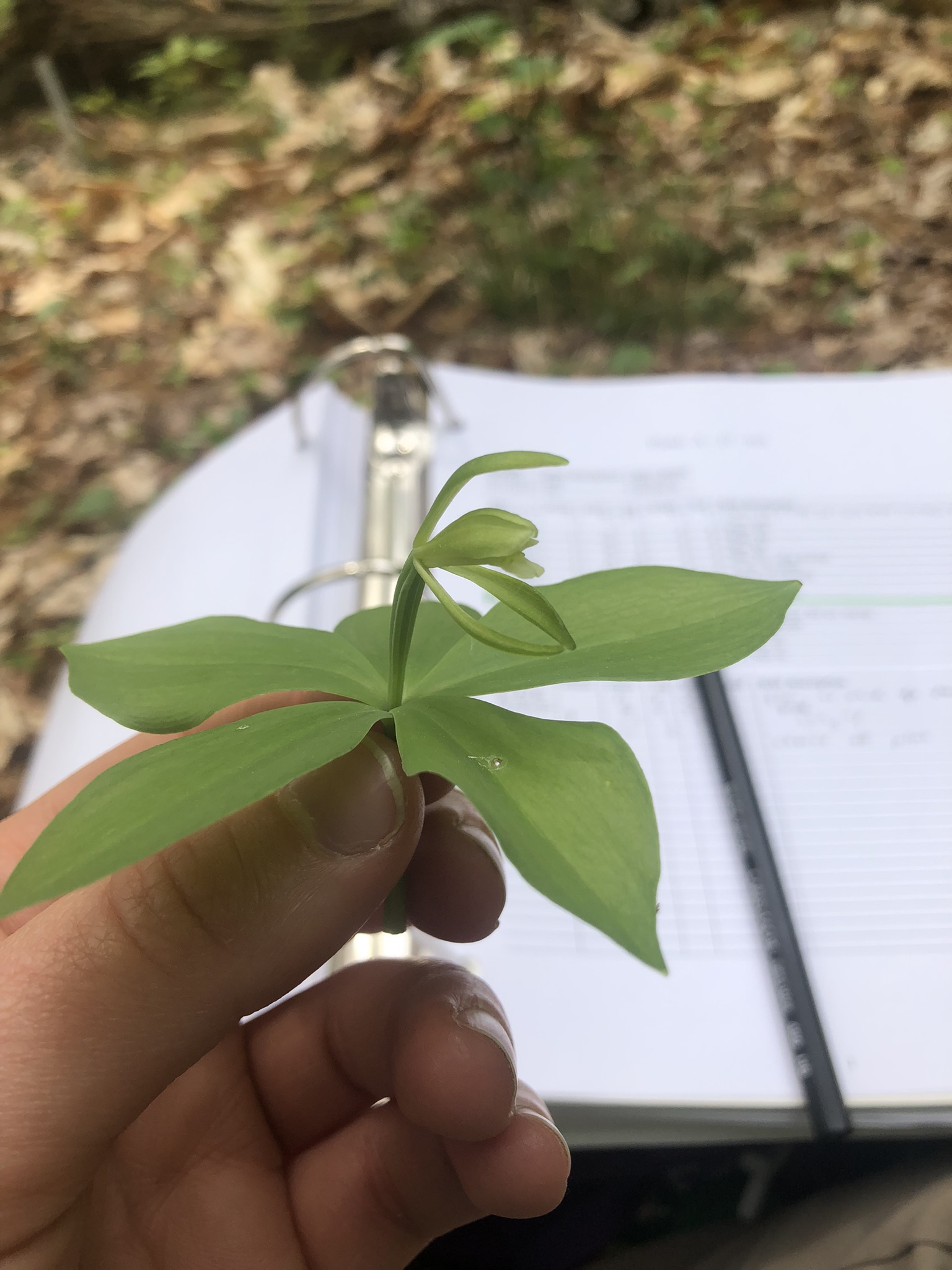

Jessamine searching for a rare alumroot (Heuchera) in Virginia. Photo credit: Rachel Braun. -

A germinant of globally vulnerable (G3) variable sedge (Carex polymorpha) from the seed bank of the New England Plant Conservation Program. Photo credit: Jessamine Finch. -

Jessamine assisting in monitoring of Pitcher's thistle (Cirsium pitcheri) in Wisconsin. Photo credit: Pati Vitt.