Anna Strong

Working for a state Natural Heritage Program gives a person good perspective about rarity in a state. Our March Conservation Champion has the challenge of working in the very big state of Texas tracking the conservation status of over 400 rare plant species. As a former CPC National Office staff member, Anna knows the importance of tracking rare plant species and is among those dedicated to making good conservation work happen. Texas and all of us say, “Thanks, Anna!”

When did you first fall in love with plants?

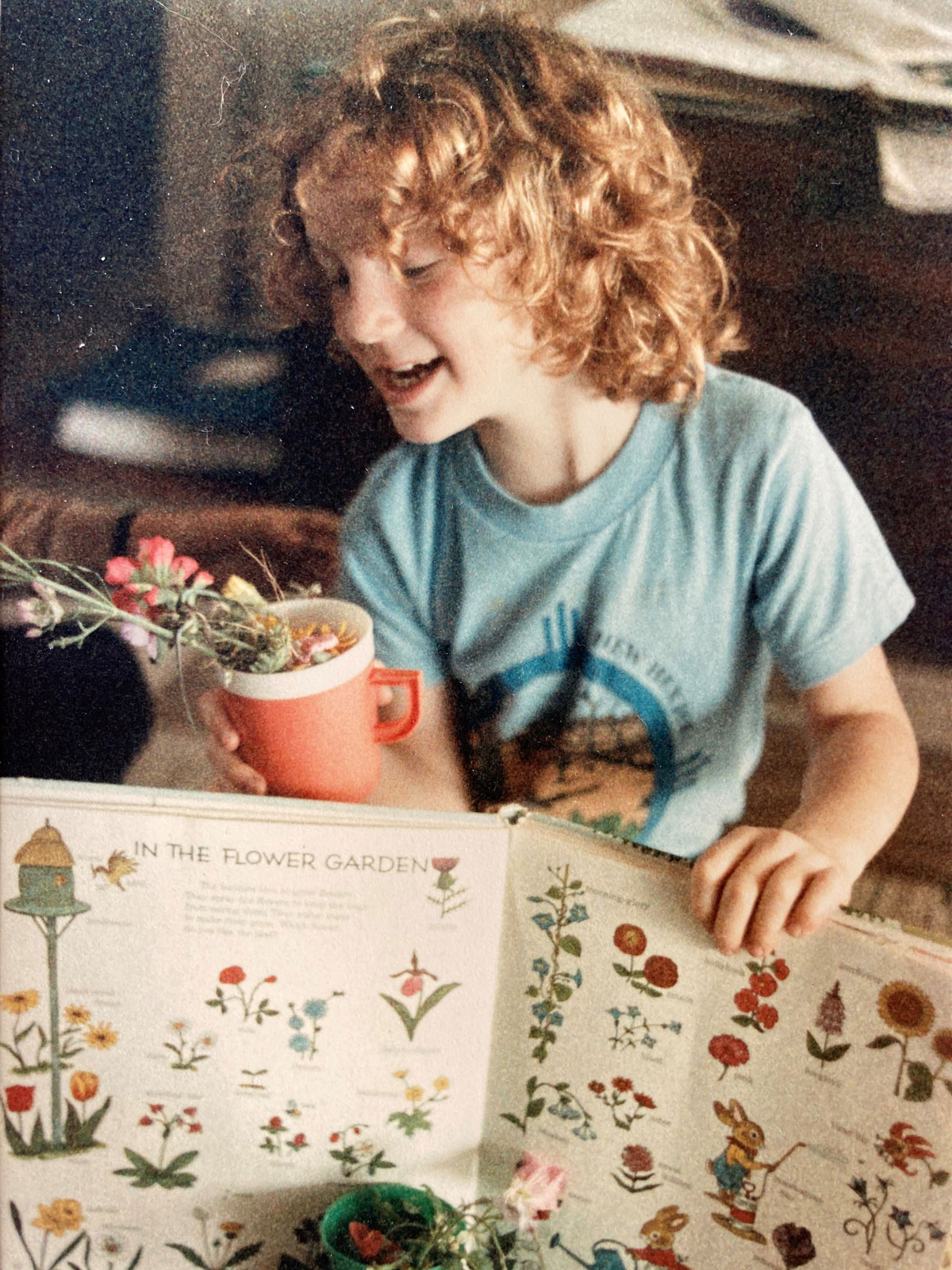

Although I did not know it would become a theme in my life, I was introduced to rare plants at a very young age. My dad has a Master’s in Botany and was one of the three initial employees of the now long-defunct Rare Plant Studies Center led by Dr. Marshall Johnston at the University of Texas at Austin. Before I was born in the 70s, they were scouting for and relocating rare plant populations and, to a limited extent, propagating rare plants.Dad was no longer working for the Center by the time I was born, but his interest in plants was very influential to both my brother and me from an early age. We went on family hikes, had plant ID lessons, camped, visited national parks, and learned about native plant gardening. By the time I was a senior in high school, I knew my major in college would be Botany.

What was your path to becoming a botanist with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department?

I was not actually keen on working on rare plants whenI was first introduced to the idea. I wanted to work on pollination biology in graduate school when I applied to Texas State University. Dr. Paula Williamson, who would become my major advisor, had applied for a Section 6 grant (a federal grant from the U.S.Fish and Wildlife Service, administered by the states to support endangered species) to study the federally endangered star cactus (Astrophytum asterias). My first thoughts were on how limiting it would be to work with a rare organism.How would I find enough plants to have a study/thesis? But I was offered a research assistantship and the university was only 30 minutes from home, so I took the challenge. After grad school, I worked for 5 years at CPC as its Conservation Projects Coordinator while it was still based in St. Louis. I then applied and received funding in 2012 for another Section 6 grant to create status assessments of a dozen Texas plants that had been petitioned for listing. I worked at the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) to write the assessments and to have access to their files and expertise. This allowed me to slip into my predecessor’s position when they retired in 2015.

What are the biggest influences on rare plants in Texas?

You may have heard that Texas is a big state. And because of its size and location, it houses a wide variety of ecosystems and geological settings. Texas has mountains, deserts, forests, coastline, scrubland, and short-, mid-and tall-grass prairies. It spans four plant hardiness zones. Annual rainfall ranges from 16” arid West Texas to 60” humid subtropical East Texas. All of this variation has created the opportunity for many rare plants to evolve and persist. But Texas is also a state of great growth. The entire eastern portion, starting from Laredo in the south and Fort Worth in the north, continues to be a rapidly growing area, with Texas projected to have the highest population increase of any U.S. state for the second decade in a row. Roads and water are needed for all these inhabitants. Texas also houses healthy agricultural and oil/gas/wind industries. All of these directly compete for the same soil as Texas’ rare plants.

What are the greatest challenges you face in your work?

You may have heard that Texas is a big state. TPWD has two botanists, a species-focused botanist (that’s me) and a rare plant community ecologist. In addition to many other things, I am responsible for our list of Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN),with over 400 plants. We also have an SGCN list of over 200 rare plant communities. Maintaining these lists is a big chore for two people in addition to our other tasks. It feels overwhelming most days

What about working with plants has surprised you?

There is so much we don’t know! And there is so much I don’t remember!

What new or upcoming research, process, or policy relating to the understanding and conservation of rare plants excites you?

My broader program, the Wildlife Diversity program, was able to hire 1½ temporary data analysts to tackle the immense backlog of plant data we have housed in paper and electronic files at the Texas Natural Diversity Database. These two new employees will be able to focus on the backlog, starting with two federally and state-listed plants in East Texas. This is not a sexy project, but we only have three full-time data specialists for seven taxa biologists and a whole state’s worth of rare plant, plant community, and animal data. To be able to zero in on plant data entry makes accessing and interpreting rare plant data easier for both our external data users and me!