Clovers on the Rebound

Not long ago, running buffalo clover (Trifolium stoloniferum) was thought by many to be extinct. Yet, this past fall, it joined a select few species considered recovered enough for delisting from the Endangered Species Act. This noteworthy event is a result of the extensive work that has gone into recovery efforts, including propagation of hundreds of plants in the Plant Lab at the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden’s Center for Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife (CREW).

Running buffalo clover has a wide range, stretching from the Midwest to the Appalachians. The species relies on habitat with clear, obvious disturbances, such as the extensive buffalo trails that crossed the region before buffalo populations suffered a precipitous decline. This unusual life history trait may be the reason that running buffalo clover was undetected between the 1940s, when it was initially thought to be extinct, and its rediscovery in 1983 by a botanist with the Nature Conservancy. This preference for disturbed regions also guides land management efforts under way to conserve the species.

Kentucky is one of the many states to rediscover populations of running buffalo clover. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has led projects there to establish new populations on private lands, reestablish populations at sites where they have disappeared, and support a research population at Eastern Kentucky University. When a large number of plants were needed to make these efforts succeed, CREW seemed the obvious choice. Brent Harrel, one of the USFWS project leads, had been impressed by a tour of the CREW facility. Other collaborators from Kentucky Nature Preserves had previously worked with CREW’s Valerie Pence, Ph.D., and her team. According to Harrel, the CREW team were the potential collaborators they approached who best “understood what our objectives were and could produce the numbers we needed.”

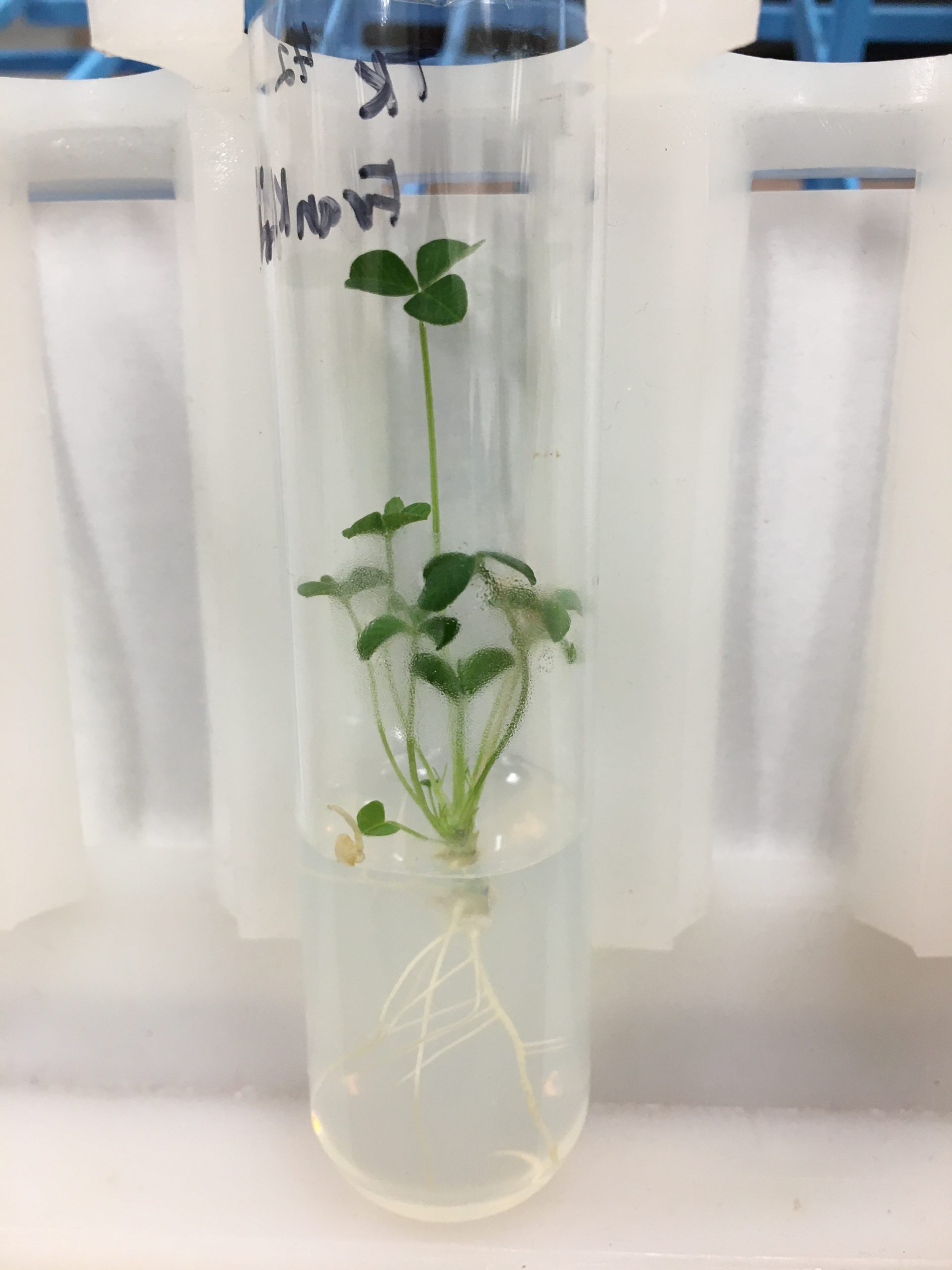

Valerie had earlier been intrigued by a 1988 study out of West Virginia University on the tissue culture propagation of running buffalo clover. The study demonstrated that the species could be propagated in vitro (in a sterile test tube environment), giving the CREW team a promising start. Once the decision for in vitro germination was made, propagation turned out to be rather straightforward, and less challenging than in many species. Scarifying (nicking) the small, hard seed with a scalpel proved to be difficult, but it gave the best germination results and became part of the final protocol.

The scalpel work is done on a sterile surface with a dissecting scope. The seeds are then placed on a simple growing medium of salts and sugar that is dilute (half the typical concentration) and has no plant growth regulators. The growing plants are protected and nourished in the in vitro system until they develop into robust seedlings with significant root development. At that stage the plants graduate to soil – but they cannot instantly transition from cozy in vitro tubes to the harsh outdoors. Once in soil, the plants are first kept in a humid environment and only gradually weaned into drier conditions, first in pots in the greenhouses and eventually outside.

Pampering the plants with a nice, controlled, in vitro environment proved very effective. Though the seeds can be scarified and germinated in soil, the combined in vitro-soil method resulted in higher efficiency with loss of many fewer plants. Plants germinated directly in soil were at the mercy of the greenhouse – too much afternoon sun or not enough water reaching the edges of a tray, caused damage or loss. Staff at the CREW tissue culture facility found it more predictable, and ultimately easier, to start the seeds in tubes.

Valerie and her team do not often get to see their plants reach their ultimate destinations. With running buffalo clover, however, they were able to participate in an outplanting (transplanting from a facility to an natural area) at a site owned by Eastern Kentucky University. The team found it incredibly satisfying to take part in the return of the species to its home.

New homes for Brent Harrel’s plants have also been established throughout Kentucky. The plants were cared for regularly in their first year and then monitored annually. A decade has passed since the work was initiated and some of the populations are doing very well. Though, as with many large reintroduction efforts, the results overall have been mixed, despite careful site selection. There is still more to be learned about the species. However, the work done to date shows that it is possible to establish new populations and expand existing ones, given appropriate conditions and management.

The delisting of running buffalo clover from the Endangered Species Act is currently pending. The USFWS will continue to keep a watchful eye on this species and encourage conservation partners to do the same. Meanwhile, Valerie and her team are expanding their propagation protocol for running buffalo clover to some of its relatives. The method seems broadly applicable. CREW has already applied the unmodified protocol to buffalo clover (T. reflexum), an at-risk species in the Eastern U.S., and – excitingly – to T. kentuckiense, a newly described clover that seems to be endemic to two counties in Kentucky. The future for these rare species is looking hopeful!

All photos (except where otherwise indicated) by Valerie Pence, courtesy of Cincinnati Botanical Gardens.