Building a Sense of Place

Visitors to Tucson—and many residents—come from various locales that are often wetter and greener. Some may feel a bit intimidated by the prickly plants, the unusual animals, and the desert they inhabit. Even long-term residents may not be acquainted with the long history and rich natural heritage of their corner of the Sonoran Desert. Fortunately, the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum helps both residents and visitors feel comfortable approaching the desert to take a closer look at its wonders. A central goal of the Museum is to help residents build a sense of place and to inspire all to live in harmony with nature.

Displays at the Museum are designed to encourage this connection, placing animals side-by-side with the plants that they depend on. Visitors can connect the presence of pollinators in the air and lizards underfoot to the plants growing among them. This visible plant-animal connection is enough to entice some people into taking native plants home to add to their own landscaping. Botany Curator, Erik Rakestraw, likes to point out how the Museum’s plant sales provide benefits to wildlife. “It is a tangible way for them to kind of partake in conservation themselves,” he states. “They can actually see the changes they make at home firsthand by adding a few plants … they can see these changes take place: the birds, bees, and lizards coming back.” Some gardeners return year after year, discussing their plant additions and observations with the nursery staff and demonstrating their joy in the plants. Native plant additions to local landscapes also serve to boost pollinator corridors throughout Tucson and keep these important ecosystem service providers thriving.

The Museum’s native plant sales are a great opportunity for people already interested in mitigating their footprint on the environment. But others may need help to move beyond a desire to recreate the green and flowery landscaping in which they grew up. The Museum shows visitors that the desert has its own beauty to offer. Its displays concentrate unique, intriguing plants and expose people to a large variety of species found in the desert. A common refrain around the Museum—“What is this plant?”—presents an opportunity to share information about the plants and the roles they play in desert ecosystems.

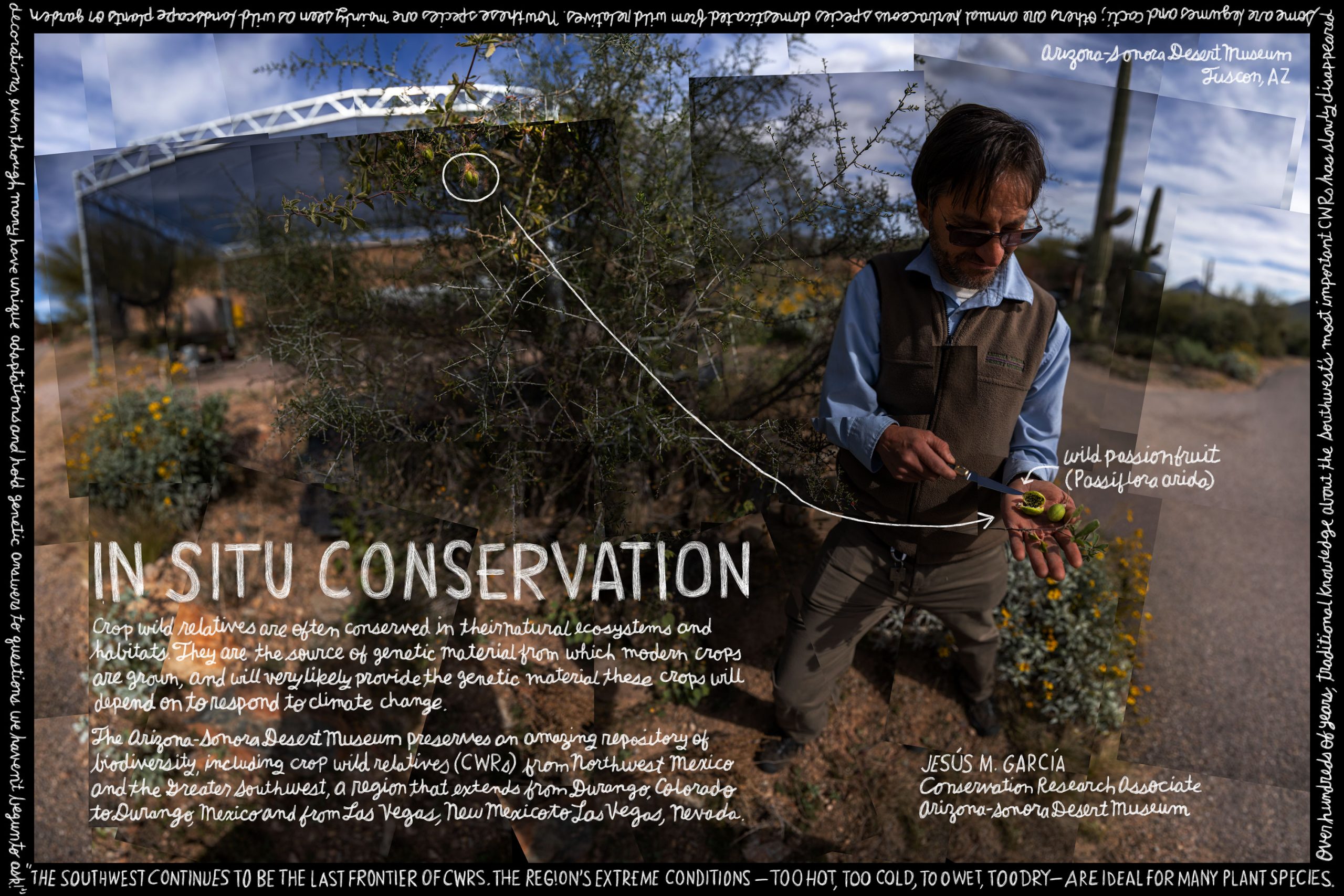

Another hook that builds interest in native plants is … their tastiness! Spicy chiltepín (Capsicum annum) and delicate passion flower (Passiflora arida) are among Erik’s edible offerings to the public. In addition to delicious treats, the Museum shares a great deal of ethnobotanical information about desert plants. Associate Research Scientist Jesús Garcia has been incorporating increasing amounts of ethnobotanical material into school kits and programs for the public. He points out that the Museum has always had a saguaro fruit harvest program, as well as strong ties to noted ethnobotanists such as Richard Felger, Mark Plotkin, and Gary Nabhan. Over time, public interest has been growing in learning how people have related to and used plants, and so have the ethnobotanical offerings of the Museum.

Jesús’ interest in plant-human relationships goes beyond the uses of plants in indigenous cultures. He helped spearhead the Kino Heritage Fruit Trees project, which grows plants brought to the region from the Spanish Mediterranean, such as pomegranate and citrus. Having grown up the Sonoran Desert south of the border, Jesús sees his own history and identity in the flavors of these plants, the blend of Hispanic influences on the desert, and indigenous traditions. The Kino Heritage Fruit Trees project exposes new transplants to Tucson to this rich history, which shows how personal identity has related to plants grown, eaten, and used in the region throughout history.

An interest in food crops native to the area is also increasing, especially in the light of climate change. Desert species are better suited to growing with less water for large food production as well as in gardens. The Museum has been involved with evaluating crops for desert agriculture and has observed an increase in the use of foods such as agave and mesquite by the public. A recent project highlights the plethora of food plants in the desert in the publication Desert Foods for a Resilient Future and is now set to expand. Wild, domesticated, and crop-wild relatives found in the Sonoran Desert offer opportunities to honor the past by understanding and exploring indigenous knowledge, as well as ways to prepare for a more arid future.

The benefits of desert crops—either native to the region or adapted from the Mediterranean or other sources—in the broader food system will only increase with climate change. Erik also sees the influence of climate change on a growing public interest in native gardens. Whether or not they attribute it directly to climate change, people are increasingly interested in how to save water and other natural resources. Jesús believes there is a greater awareness of the need to “understand the beauty of the place where you live, but also understand the nature in a way that [lets you recognize] that this requires less maintenance, less water, less money.”

At the Desert Museum, people find inspiration to become more in tune with nature and discover ways to create their own mini-Museum at home. Whether they focus on plants that draw in pollinators and other animals, or on plants that save water but are also useful or taste good, the desert has plenty to offer. Through plants cultivated for display and sale, and programs shared with the public, the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum encourages visitors to develop strong connections to their desert home and inspires them to live in harmony with it.