Save Plants: April 2018 Newsletter

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

April 2018 Newsletter

In this month’s issue of Save Plants, we tackle the notion of what it means to be a “weed.” The old adage that a weed is “any plant growing where you don’t want it to” is an appropriate description. But more often than not people think of a weed as any unattractive or otherwise undesirable plant. Using this definition, many native species, even endangered plants, can be characterized as weeds simply because they are not showy. But many plants that are truly detrimental weeds can be quite showy, often the result of horticulture introductions into areas outside their native range. And those ugly little imperiled plants without a use? Well, they are in fact quite useful ecologically as many other species including insects and other pollinators depend on them for survival. Read on to learn about what it means to be a weed and, more importantly, what it means to not be a weed. You will soon see that beauty—and the weedy—are not all that meet the eye of the beholder.

To Be, or Not to Be, a Weed

This month we are looking at plants that are endangered but could be mistaken for “weeds.” Both appearance and/or behavior can account for misconceptions and perceptions. What happens when there are plants that display weed-like characteristics, yet aren’t weeds? What happens when those plants are also endangered? How do we address the perception of “weed” to obtain and maintain protection status? If a plant is thought of as a weed, how do you convince anyone of the need to preserve it? The answer? It’s complicated. These questions are the subject of larger, and complex, debates.

James Lange of Fairchild Botanic Garden states that you can separate these plants into categories of “weedy” behavior, and “weedy” appearance.

“Weedy” Behavior:

“The Tephrosia spp. is a very aggressive prostrate vine. The Chromolaena frustrata and Ageratum maritimum are considered garden weeds and disturbance species. The Dalea carthagenensis is viewed as a weed throughout South and Central America. And they all have in common that they are rare plants and actually thrive in marginal habitats in terms of weedy potential.

“There are a number of rare species that absolutely thrive in mowed areas, and traffic right-of-ways, but are extremely rare in natural habitats, making for complicated conservation decisions.

“In Florida, a state-endangered liana, hoopvine (Trichostigma octandra) sometimes reaches nuisance levels in preserves where it is found. It weighs down the canopy and shades the understory. Managers are faced with the dilemma of maintaining habitat while preserving the existence of this rare species.”

Another example of “weedy” behavior would be Ambrosia linearis, a plant in the Center for Plant Conservation National Collection that fits the profile of a rare species that can sometimes behave as a weed. Jim Locklear of Lauritzen Gardens notes that Ambrosia linearis “is a G3 species that is endemic to the plains of eastern Colorado. It occurs naturally around the outer margins of playas, which are temporarily flooded lakes that occur in grasslands. It also occurs along upper terraces of intermittent streams in the region. Ambrosia linearis can also occur in dense stands in roadside ditches and along gravel roads in the area. It appears the plant spreads into these areas when roads have bisected its natural habitat. It is not a problem in these areas, and actually probably helps prevent erosion along roadsides. These roadside populations are most likely not controlled as they seem to be confined to ditches and occur in rural, very sparsely populated areas. However, routine road maintenance activities such as periodic grading of the road bed could have a negative impact. The greater challenge could come in trying to encourage preservation of high-quality occurrences in natural habitat when the plant can also grow as a roadside weed.

“Fortunately, playas are recognized as unique landscape features in the Great Plains and of high conservation value because of their importance to migrating shorebirds and waterfowl. The unique association of Ambrosia linearis with playa habitat just adds to the importance of preservation.”

“Weedy” Appearance:

According to James Lange, “there are rare plants that may have a “weedy” appearance that could make it difficult to push for protection. Several of our true endemics are diminutive plants with the reproductive potential of weeds but are true habitat specialists. Chamaesyce spp., Poinsettia pinetorum, Tragia saxicola come to mind but there are several others. This makes sense given that in order to evolve in the brief period of geologic time South Florida has been around you’d have to reproduce a lot.

“These species can be a tough sell from a conservation standpoint because they are non-charismatic, weedy-looking things. For example, Two-Spike Crabgrass (Digitaria pauciflora) which fits in this category, just by its nature of being a crabgrass, but, again, a true habitat specialist.”

The Tale of a True Habitat Specialist

“Long ago, one rebellious sister in the crabgrass genus decided to quit her weedy ways. She diverged from more than 200 other Digitaria species (congeners), settled in a remote Florida swamp and traded her hardiness for beauty. She grew tall and acquired a bluish sheen. Her new growth sported soft, fuzzy hair; her old growth, a distinctive zig-zag, checkered pattern. She became so attractive that she didn’t feel the need to produce as many flowers. Because she loved the swamp so much, she never bothered to venture out to other lands, even though human alteration of natural water levels has recently given her much cause for concern.” Jennifer Possley, Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Virtual Herbarium

A Weed or Not a Weed, That is The Question

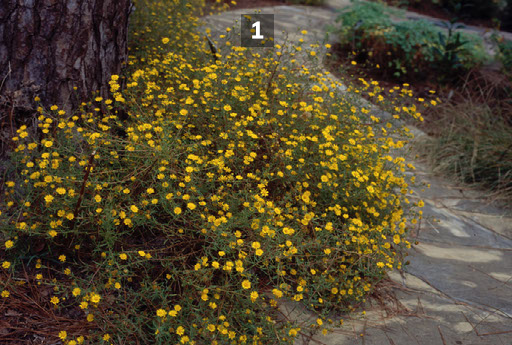

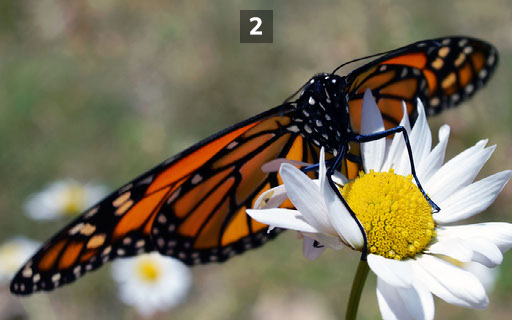

Test your skills: determine which plants are considered weeds or invasives and which are rare plants. (The answers are at the end of the newsletter.)

The National Tropical Botanical Garden announced Dr. David H. Lorence as recipient of the prestigious 2017 Robert Allerton Award for Excellence in Tropical Botany or Horticulture. Read more here.

News

Jennifer Ramp Neale, PhD, Director of Research & Conservation at Denver Botanic Gardens, was recently interviewed for the podcast People Behind the Science. Her topic was “Conducting Research to Conserve Colorado’s Rare Plants.” You can listen to the April 9th podcast here.

Rookies for Recovery!

The Rookies for Recovery Internship Program is an exciting new venture cultivated through a partnership between the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the Center for Plant Conservation, and the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research.

Through this program, interns will be chosen based on their competitive qualifications, previous experience, eagerness to learn, and interest in the fields of biological science and conservation. This program, in its pilot year, will be selecting five interns to undergo an intensive training led by field researchers and government agency representatives to prepare them for a five-month full-time, paid internship placement within a BLM office or field location. During their program, interns will engage with science and policy, gain skills and professional development strategy and be exposed to the inner workings of management techniques for federally listed species. This year opportunities include placement in:

- BLM Royal Gorge Field Office, Colorado

Working on inventory, monitoring, and banding of Mexican spotted owls, assessing and restoring lynx habitat, and the development and implementation of a bat acoustic monitoring project. Apply here.

- Grants Pass, Oregon on the Cook’s lomatium Recovery Project and the Gentner’s Fritillary Recovery Project

Mapping, seed collecting/banking, invasive species monitoring, and mitigation strategy planning. Apply here.

- Coachella Valley, California

Tracking disturbance in habitat for Peninsular bighorn sheep, native seed collection for desert tortoise habitat restoration, and restoring habitat for desert pupfish. Apply here.

- BLM Central Coast Field Office in Marina, California

Leading a radio-telemetry study and measuring habitat requirements for the endangered blunt-nosed leopard lizard. Apply here.

- BLM El Centro Field Office in El Centro, California

Implementing the Flat-tailed Horned Lizard Rangewide Management Strategy, creating maps of Quino checkerspot sightings and suitable habitat, and identifying and monitoring the condition and use of water sources in Peninsular bighorn sheep habitat. Apply here.

For more information and to apply please visit the San Diego Zoo Jobs List website

Answers to plant quiz above: 1. Houston Camphor daisy (Rare), 2. Ox-Eye Daisy with monarch butterfly (Weed), 3. Two-Spike Crabgrass (Rare), 4. Veldt Grass (Weed), 5. Golden Indian Paintbrush (Rare), 6. Texas Wild Rice (Rare), 7. Oxalis pes-caprae (Weed)

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today